Chinese Investment: Europe vs. the United States

Chinese direct investment in the United States and Europe has grown fast since 2008. In the past two years, Europe has attracted twice as much investment as the US as Chinese investors seized commercial opportunities arising from the European crisis. Flows to the US can be expected to remain strong on the back of the US economic recovery and growing Chinese interest in high tech and modern service assets. However, policy and politics have become important factors for investment in sectors like infrastructure and high tech, and they will become even more critical for future deal making.

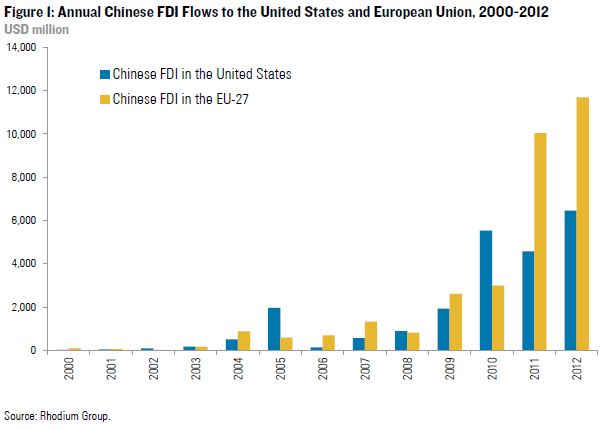

Both Europe and the United States attracted increasing flows of Chinese direct investment since 2008. After a similar take-off phase, patterns diverged in the past two years with Europe receiving almost twice as much investment as the US. Annual flows to the EU grew from less than one billion annually before 2008 to an average of 3 billion in 2009 and 2010, before tripling to more than $10 billion in the past two years. In the US, investment surged from less than 1 billion in 2008 to $5 billion in 2010, before dropping again to $4.7 billion in 2011. In 2012 investment reached a new record high of $6.5 billion, but values remained below the levels seen in the EU in the past two years (Figure 1).

The upward deviation of capital flows to Europe in past two years was mostly driven by commercial opportunities resulting from the fiscal and economic crisis in the Eurozone. Chinese investors seized opportunities to buy into cash-strapped European industrials and assets promising stable long-term returns such as utilities and other infrastructure.

Targeted Industries

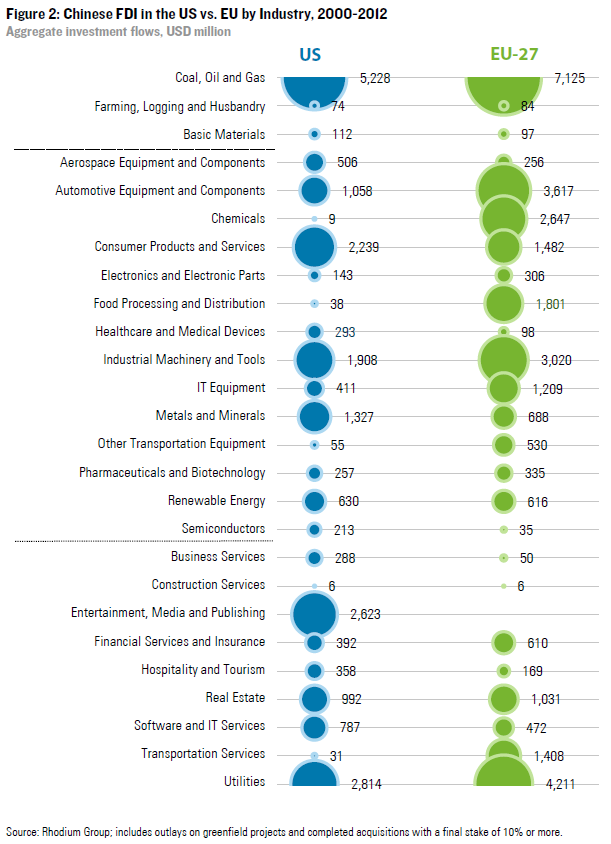

Natural resources were a prime target of Chinese overseas acquisitions globally and they are also the primary target in the US and EU. After the CNOOC-Unocal incident in 2005, Chinese firms have made a comeback in the US energy sector with investments in unconventional oil and gas resources of more than $5 billion since 2010. In Europe, Chinese firms spent more than $7 billion on firms in the oil and gas industry, including local exploration and production joint ventures (Sinopec-Talisman), local refining assets (Petrochina-INEOS) and EU-headquartered firms with global upstream assets (Sinopec-Emerald Energy).

The greatest divergence can be seen in advanced industrial assets. Chinese firms are eager to acquire advanced manufacturing assets that allow them to modernize technology and move up the value chain. The crisis in Europe offered an attractive opportunity for investors to snap up medium-sized industrials with experienced staff, advanced technology and products that provide them with an advantage in the Chinese market. Examples are the industrial machinery and automotive industries, where Chinese investors spent a combined $6 billion, compared to less than $3 billion in the US. In light of a recession at home, European firms such as Volvo, Putzmeister or Ferretti welcomed Chinese partners injecting capital and helping them leverage their products in fast-growing Asian markets.

Europe also attracted more investment in utilities and transportation infrastructure, as governments were forced to privatize assets and attract foreign capital. State-owned enterprises and sovereign investment vehicles seized the opportunity and invested more than $5 billion in EU transportation infrastructure and utilities through 2012, including a stake by China’s sovereign wealth fund in London’s Heathrow Airport. The US on the other hand attracted close to zero investment in transportation infrastructure, and the $3 billion of Chinese investment in utilities targeted firms with the majority of assets located outside of the US (AES, Intergen).

The US has beat out Europe in several high-tech clusters, for example aviation and IT services, but investment levels in these industries remained low. Looking forward, Chinese interest in these industries will increase as firms become more capable managing and integrating those high-tech assets. Recent transactions including the Wanxiang-A123 and BGI-Complete Genomics acquisitions show that deal flow in those industries is already picking up.

Another new trend that will help sustain flows to the US is greater Chinese interest in advanced service sector assets. Firms are gearing up for above-trend growth of services in a rebalanced Chinese economy, and overseas operations will help them gain a competitive advantage in the form of human talent, experience, brand value and other things. Financial services, entertainment and IT services will attract great interest in coming years, and with its world-class service sector the US is well positioned for this trend. The $2.6 billion acquisition of movie theater chain AMC by Dalian Wanda and the announced $4.2 billion takeover of International Lease Finance Corp (ILFC) illustrate the potential for larger-scale deals in these industries.

The Role of Policy and Politics

While commercial opportunities are driving deal-making, our data set also highlights the importance of political factors for Chinese investment patterns in both economies. Differences in national security screenings and the level of public scrutiny are already impacting flows in a number of industries.

Infrastructure is the most obvious example, where European officials welcomed Chinese investment in airports, electricity grids and ports. Including utilities, Chinese firms spent close to $6 billion on European infrastructure assets, highlighting the great demand for passive long-term investments in safe haven economies. Investments in US infrastructure assets would make commercial sense for Chinese state enterprises and sovereign investment vehicles as well, but the reactions to similar earlier investments such as the Dubai Ports World controversy in 2006 seem to have made Chinese investors cautious about US infrastructure plays.

National security concerns are also affecting investment in high-tech sectors. Chinese telecommunications equipment firms for example spent more than three times as much in Europe than in the US, where CFIUS has interfered with several deals and firms have seen their business prospects diminished by intervention from US government officials, members of Congress and the security community. Another example is aviation, where the US received about twice as much investment as the EU, but several deals fell apart due to security concerns over the dual application of those technologies. The $1.8 billion takeover of Hawker Beechcraft in 2012, for example, was abandoned partially due to concerns over the separation of defense-related business activities.

Outlook

As the Chinese economy matures and firms become more experienced at doing business abroad, Chinese interest in advanced economy assets will continue to be strong in coming years. Europe has attracted more Chinese capital in past two years, but this was as a cyclical deviation rather than a structural phenomenon. The United States remain an attractive place for Chinese companies to invest and its attraction will only grow with stronger signs of economic recovery and increasing appetite for service sector assets.

The political response will be critical for future deal-making in both economies. National security reviews and politicization of deals are already impacting investment patterns, particularly in US infrastructure and high tech industries. Looking forward, political risk for Chinese buyers can be expected to further increase: governments will have to handle a much larger number of Chinese transactions than in the past; they will have to adapt their review criteria and mechanisms to technological change and new security assessments; and they will have to find ways to address new challenges such as competitive advantages of state-owned enterprises or reciprocity in market access. In addition, it is likely that other bilateral tensions — such as the recent debates over state-sponsored cyber espionage or accounting frauds – will spill over into the cross-border investment arena, which will further increase the risk of politicization outside of the formal government screening process.