China’s Manufacturing FDI in ASEAN Grew Rapidly, But Faces Tariff Headwinds

ASEAN has become the top destination for Chinese manufacturing FDI by number of announced transactions, but US tariffs of more than 30% would deal a major blow to the region’s diversification boom and China’s FDI there.

Since the first US-China trade war, ASEAN has emerged as the main destination for firms diversifying their supply chains away from China. Now, hefty reciprocal tariffs on ASEAN economies—delayed for just 90 days—are putting this success at risk. Ongoing negotiations will seek to reduce ASEAN’s ballooning trade surplus with the US and limit the role of Chinese value add and firms in ASEAN exports to the US. This note draws from our China Cross-Border Monitor database to unpack Chinese investors’ role in the region’s manufacturing sector over the past decade and likely place going forward. We find that:

- ASEAN has become the top destination for Chinese manufacturing FDI by number of announced transactions, mainly driven by geopolitical risks and regulatory and tariff barriers. While the US and EU also increased their investment, the sharp spike in Chinese FDI has made China one of the top foreign investors in the region.

- Much of US import diversification through ASEAN export hubs has been supported by Chinese firms. Chinese and foreign MNCs often relocate to ASEAN in tandem. Any disruption to Chinese-owned supply chains will impact foreign-owned activities.

- There is no clear China+1 destination. Much of the region is attracting Chinese FDI, leading to distributed supply chains across sectors and countries.

- Chinese firms have proved extremely nimble in calibrating their ASEAN footprint as regulatory or geopolitical developments demanded it. This creates conditions for a whack-a-mole process that could lead to more drastic reactions, especially from the US.

- US tariffs of more than 30% would deal a major blow to ASEAN’s diversification boom and China’s FDI in the region. ASEAN negotiators could soften the blow by advocating for a high tariff differential between ASEAN and China and continued access to Chinese inputs for a few more years.

Chinese FDI in global context

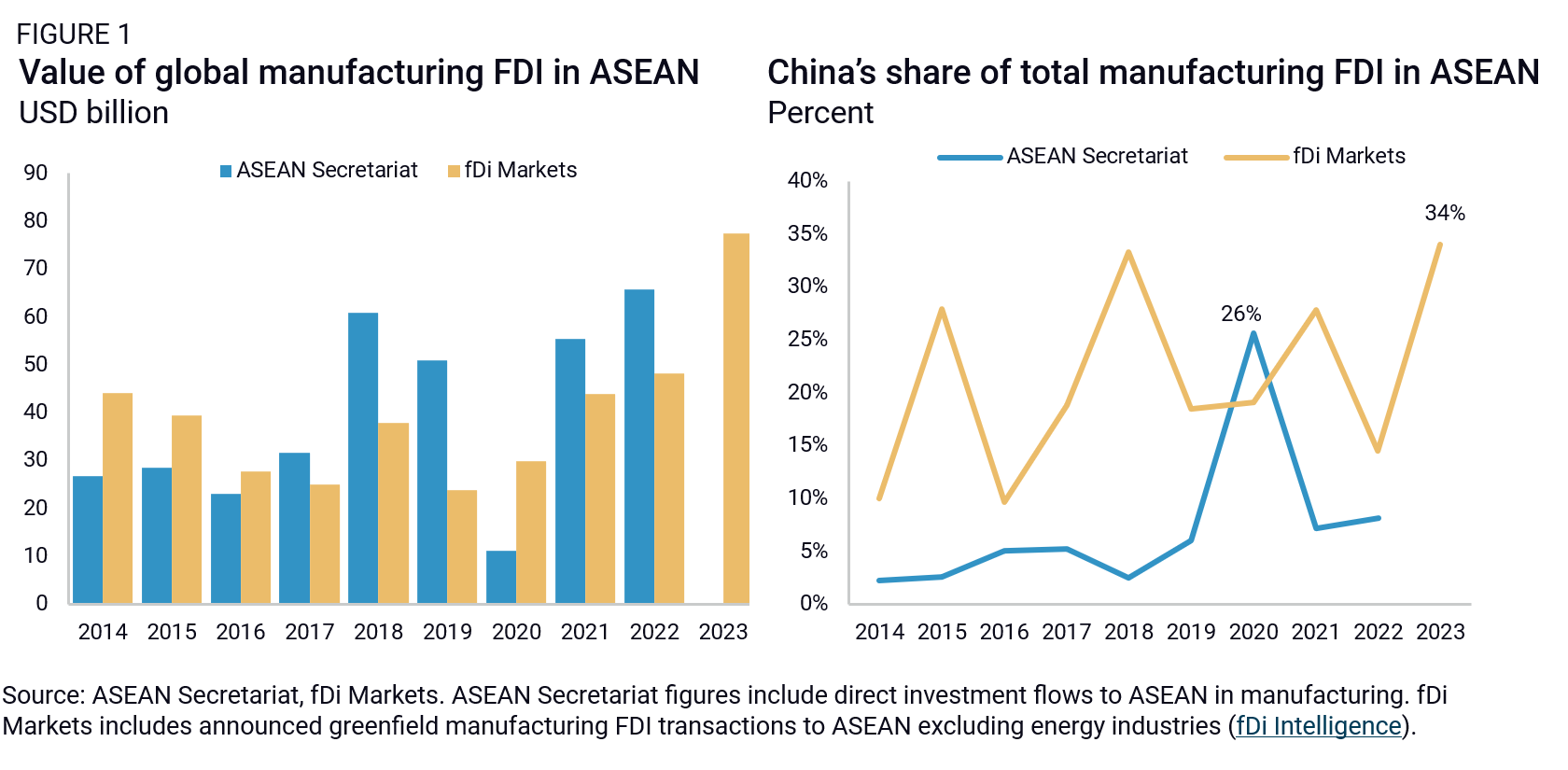

Global manufacturing investment in the ten countries of ASEAN has boomed since 2017.1 Official ASEAN data shows FDI in the region averaged $30 billion annually from 2013 to 2017, and then grew to $60.8 billion in 2018. Excluding the drastic drop in 2020 from COVID-19 restrictions, the average yearly value from 2018 to 2022 was $58 billion (Figure 1). According to data from fDi Markets, the trend continued in 2023, jumping another 61% from 2022.

The drastic increase of FDI in 2018 was driven by a global trade and investment scramble kicked off by the first US-China trade war in 2017, as well as high growth rates in ASEAN’s major economies at the time. In contrast, greenfield FDI in China decreased quickly since 2017. COVID-19 supply chain disruptions and continued US-China competition and associated de-risking policies under the Biden administration contributed to persistently high investment levels as firms sought to diversify their operations out of China.

Chinese companies were a sizeable driver of this trend, though different datasets put China’s role at slightly different levels. According to official ASEAN data, US firms are still by far the main manufacturing investors in the region, with 25% of investment over 2018-2022, followed by Japan (11%) and the EU (10%). China’s share increased quickly from 2018 but remains around 8%. Data from fDi Markets, on the other hand, puts China’s contribution much higher, at roughly 25%.

In reality, contributions from Chinese firms are likely even higher. The ASEAN Secretariat’s figures don’t account for the use of holding companies and offshore vehicles for investment, which are especially pronounced in China’s case as a significant share of its outbound FDI is routed through Hong Kong. Neither source adequately reflects Chinese capital flowing to ASEAN through Singapore either. Host countries’ official data illustrate the significance of these flows. Vietnam’s official 2023 figures show that Singapore and Hong Kong ranked among the top three sources of FDI, together accounting for 31% of inflows—while only 12% was officially attributed to China.

Breaking down China’s manufacturing FDI in ASEAN

Rhodium Group’s China Cross-Border Monitor (CBM) database of verified investment transactions provides a granular view of Chinese FDI in ASEAN’s manufacturing sector. By tracking announced transactions, the database captures shifts in investor sentiment as they unfold, sidestepping the timing and geographic distortions often found in official statistics. It also allows us to break down the trend further across economies, sectors, and investment types—including both M&A and greenfield transactions—offering a more accurate picture of Chinese capital flows into the region.

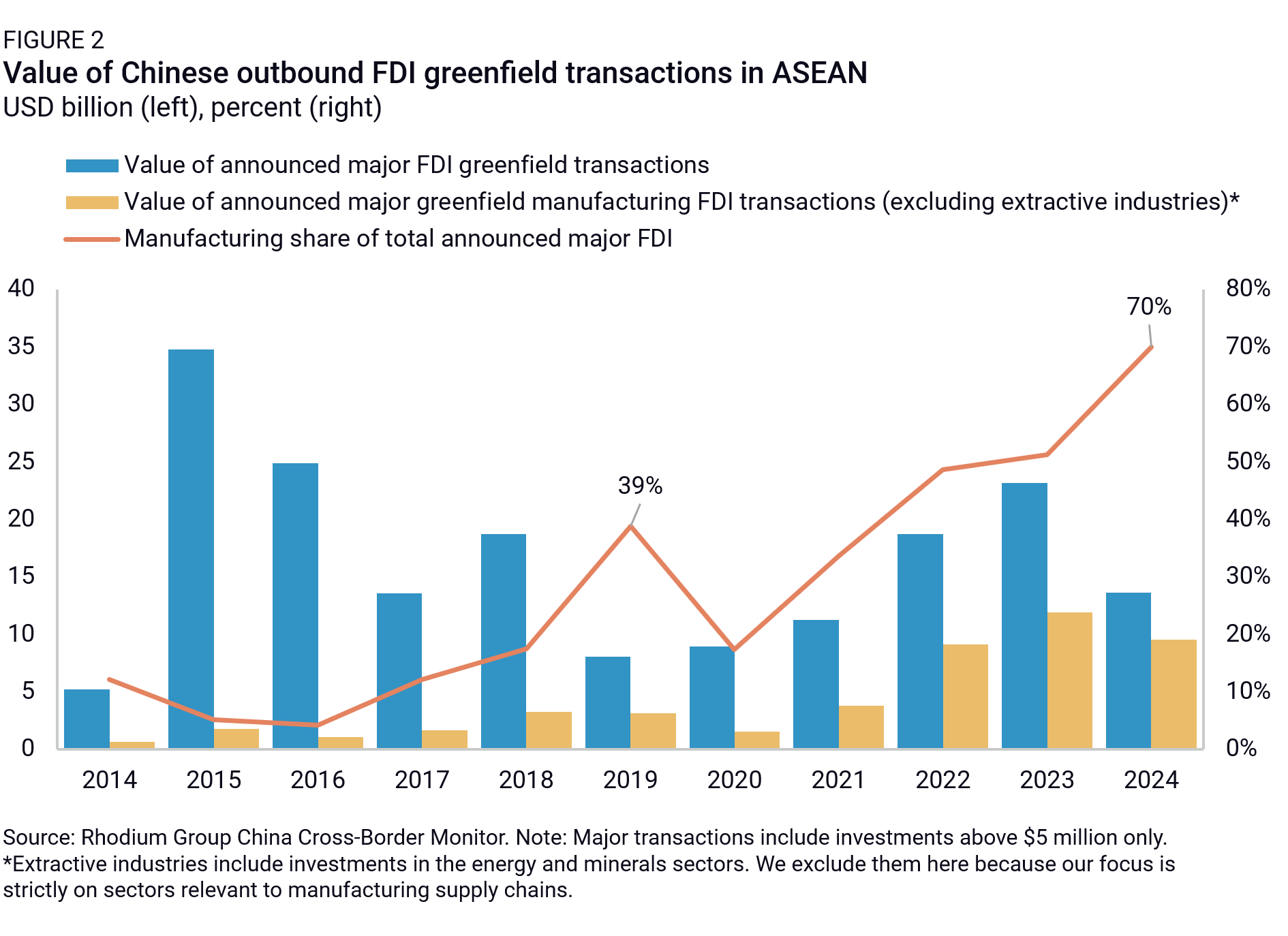

Data from the CBM shows that Chinese greenfield manufacturing FDI into the region increased slowly but persistently from 2010 to 2017 on the back of high GDP growth in ASEAN and rising costs in China. ASEAN’s geographic and cultural proximity likely played a role in Chinese firms’ decisions, as well as trade integration with China under the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area and strong manufacturing capabilities (Figure 2).

In 2018, however, manufacturing FDI almost doubled year on year, likely as a response to the first wave of US tariffs on Chinese exports (Figure 3). From 2018 to 2021, levels remained elevated, about three times above the 2014-2017 average. They then rose again starting in 2022, after zero-COVID restrictions were lifted and Chinese borders re-opened. This uptick significantly boosted Chinese FDI levels, reaching $10 billion on average over the past three years, compared to $2.7 billion the previous five years. Chinese FDI in the region was increasingly dominated by manufacturing investments—reaching more than half of total Chinese FDI in ASEAN in 2024. ASEAN’s share in China’s count of global FDI transactions also grew, averaging 45% over the past three years.

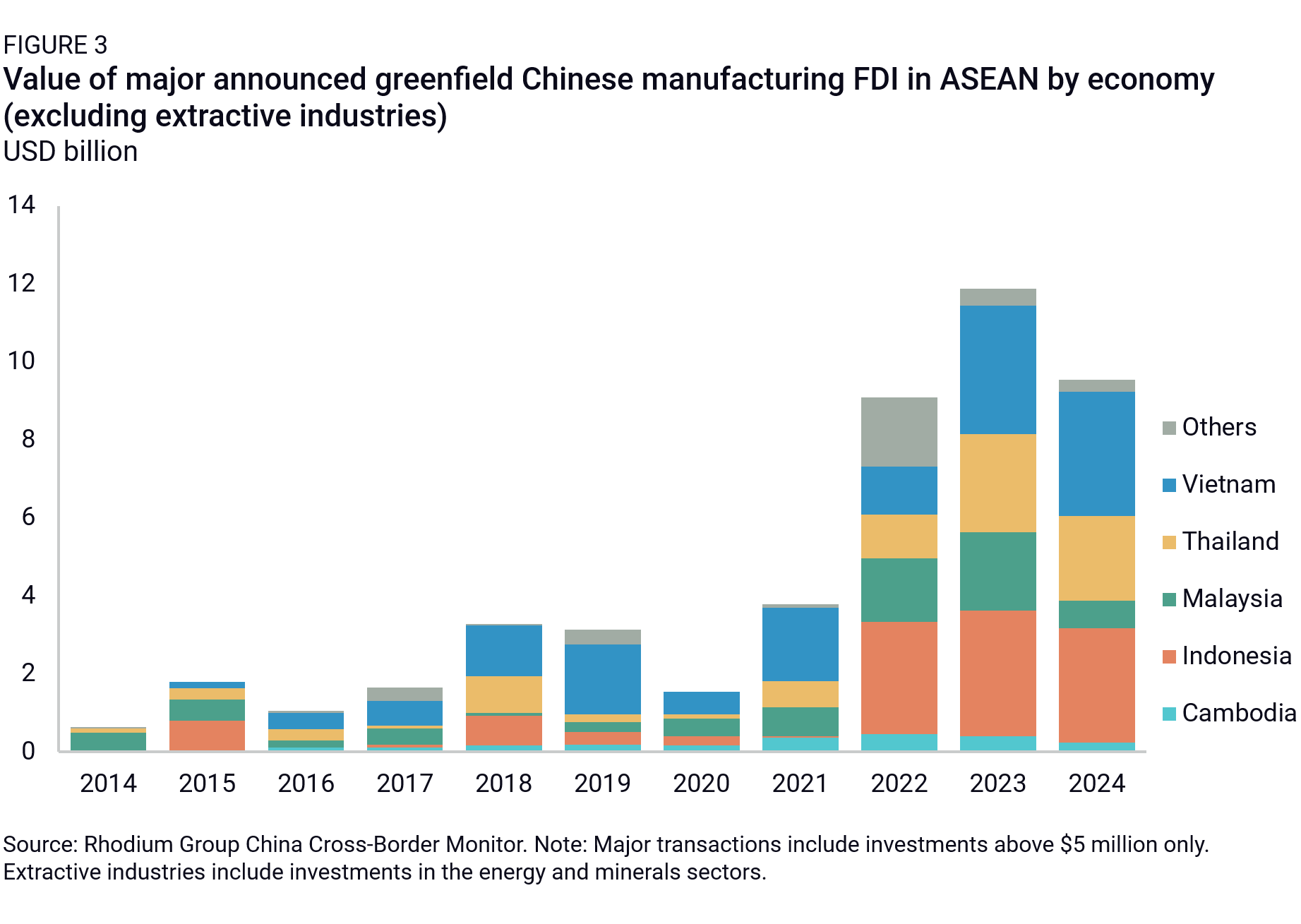

Four economies have historically attracted the lion’s share of China’s investment into the region: Indonesia and Vietnam (together about 56% of total value in 2018-2024), as well as Thailand (18%) and Malaysia (14%). Recently, Indonesia has widened its lead, making up 30% of total FDI value over the past three years. This was driven by a series of capital-intensive transactions in the electric vehicle industry. However, this understates the popularity of Thailand, Vietnam, and Malaysia, which attract significant small and medium-sized investments. Together, they made up 77% of transaction count over the past three years.

Some countries are left out of the picture. Singapore attracted some manufacturing interest over the period, particularly in high-tech industries like pharmaceuticals and semiconductors. Yet it remains first and foremost a destination for M&A, as well as Chinese business services and real estate investments. The Philippines and Brunei are almost absent, too. Both countries tend to attract high levels of Chinese investment in energy and raw material processing but are much less popular destinations for manufacturing. Finally, Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia attract low investment values, which is understandable due to their limited size. Still, Cambodia has doubled the number of major Chinese manufacturing transactions it captured in the past three years.

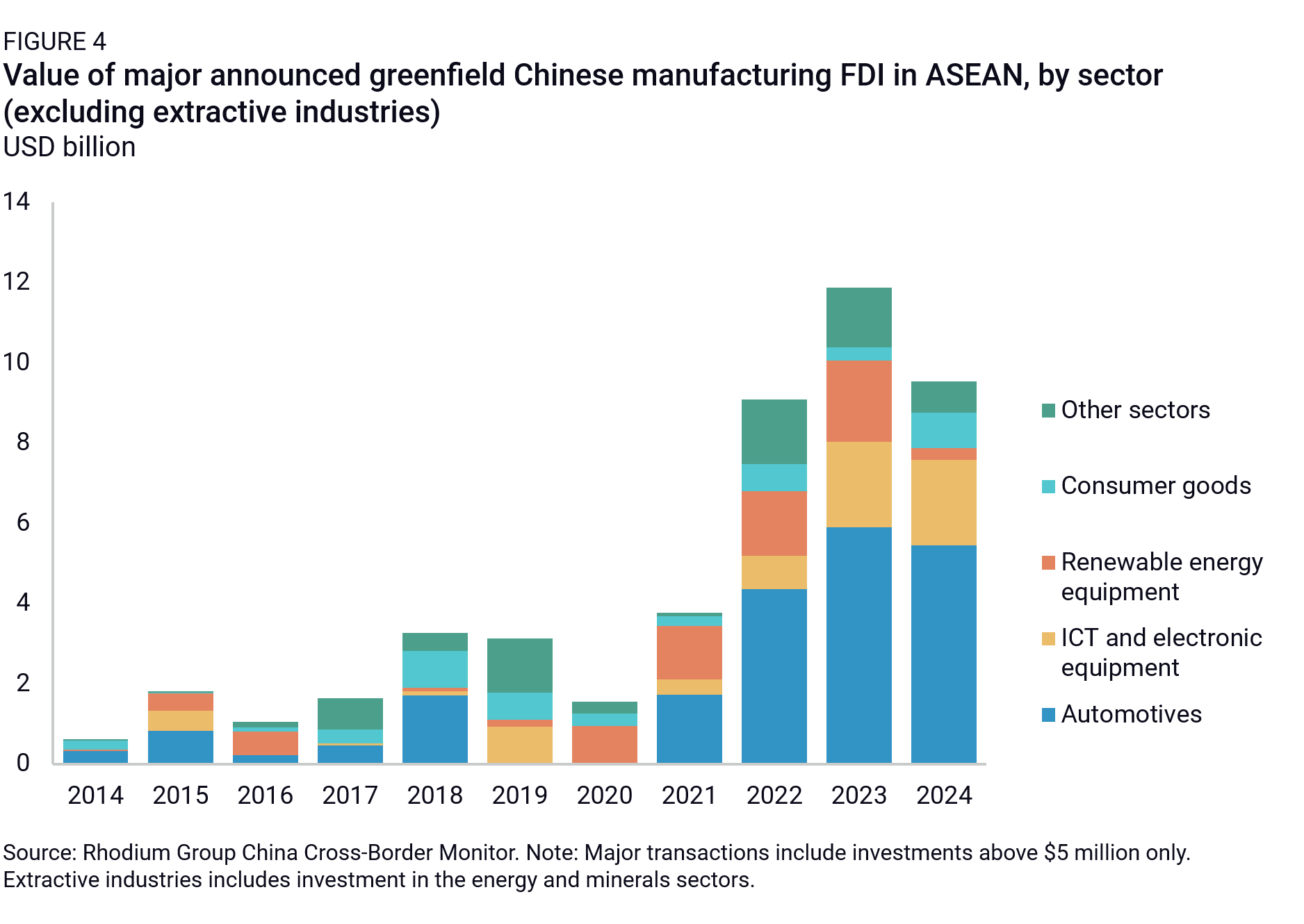

Over the past seven years, four sectors have dominated China’s FDI into ASEAN countries with over 86% of investment value: automotives (capturing 45% of total FDI since 2018), ICT and electronics (15%), renewable energy equipment (15%), and consumer goods (9%). These sectors dominate the count of transactions too, but with greater weight of capital-light sectors including ICT and electronics (22%) and consumer sectors (19%). A closer look at these industries helps explain the drivers of China’s manufacturing push into ASEAN.

Consumer goods

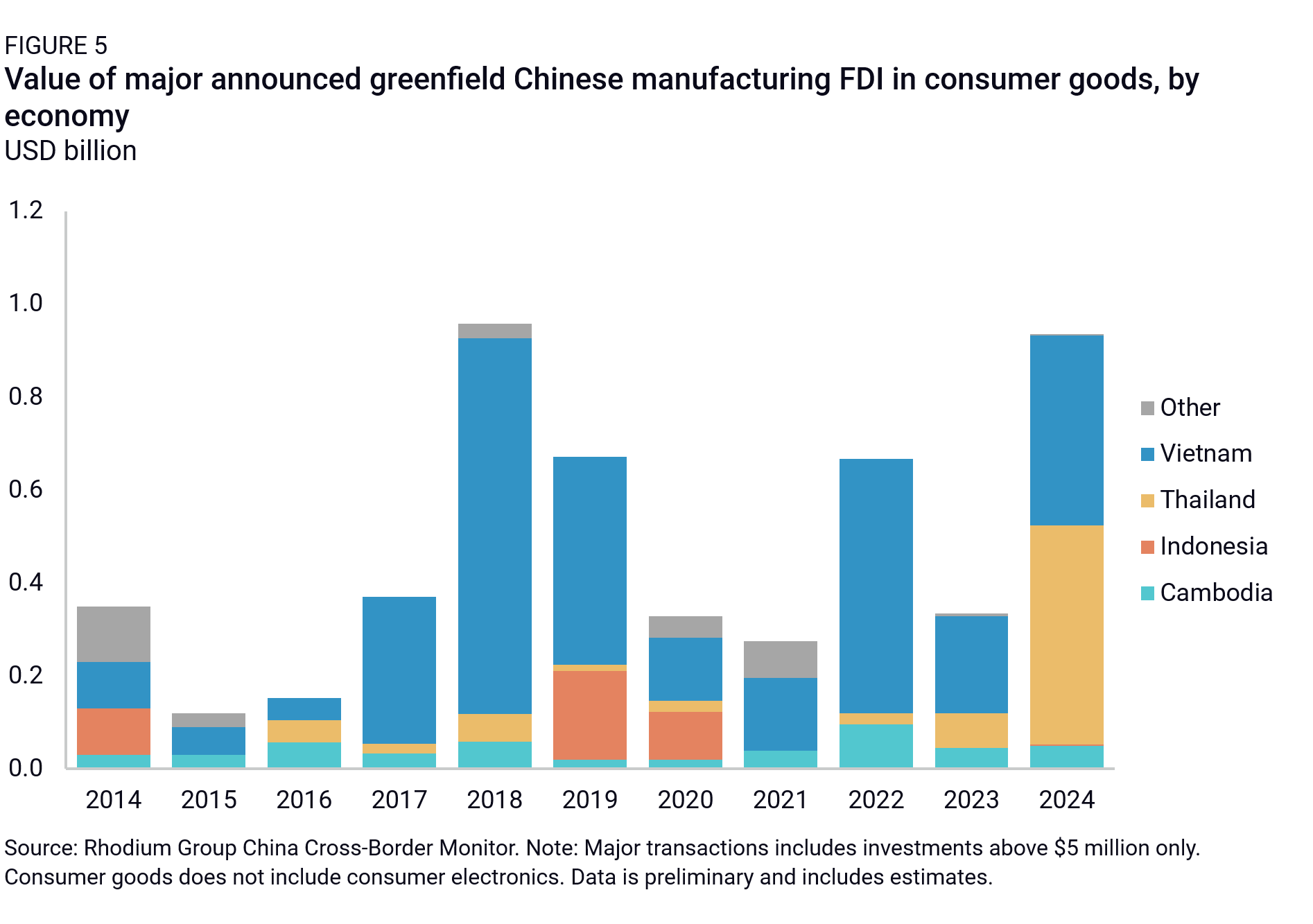

Chinese manufacturing of consumer goods—textiles, apparel, and furniture—was among the first to shift offshore, as rising wages at home pushed low-margin production toward cheaper economies. Southeast Asia emerged as the natural destination, offering a potent mix of cost advantages, logistical proximity, and trade-access arbitrage. Since the mid-2010s, the pace of investment has accelerated. Vietnam captured nearly two-thirds of announced Chinese greenfield projects in the sector—a dominance underpinned by its position in global supply chains and preferential access to both the US and EU markets (Figure 5).

While China’s initial wave of investment was structurally driven by cost and capacity constraints, the landscape changed with the onset of the US–China trade war. New tariffs on Chinese exports catalyzed a second, more reactive phase of manufacturing FDI. In sectors like household appliances and furniture—hit with US tariffs of up to 25%—Chinese firms moved final assembly of goods to Southeast Asia, particularly Vietnam, and increasingly, Cambodia and Indonesia. The value of investments in these industries rose significantly, from an average of $240 million annually between 2014 and 2017 to $560 million per year from 2018 to 2021. While export orientation remains dominant, part of these FDI flows also targeted rising local consumer demand, including through a series of investment in e-commerce firms Lazada in Singapore and Tokopedia in Indonesia by Alibaba from 2016.

Post-pandemic, the logic behind China’s offshore manufacturing remains intact but has grown more strategic and long-term. Investment activity remained strong, peaking at $935 million in 2024, with a growing focus on higher-value segments. Thailand, for example, has emerged as a key destination for home appliances and consumer durables, supported by stronger infrastructure and local demand. At the same time, firms continue to diversify beyond Vietnam into lower-capex, labor-intensive economies, especially in Cambodia.

ICT and electronics

Chinese electronics manufacturing began shifting offshore in the mid-2010s, a trend that gained momentum after the US–China trade war. Average annual investment value doubled after 2017 and nearly doubled again in the post-COVID period, particularly from 2023 onward.2 Even though electronics benefited from significant tariff carve-outs during the first US-China trade war, large Western technology firms sought to reduce their reliance on China and gain access to new growth markets as intense competition started squeezing them out of the Chinese market. Chinese suppliers, in turn, followed to maintain access to key customers and remain embedded in global production networks.

In semiconductors, Chinese firms such as JCET, TongFu Microelectronics, and Yangzhou Yangjie Electronics have established operations in the region providing outsourced assembly and testing services to Western clients. Malaysia captured 67% of regional semiconductor investment, emerging as a key hub for global players such as Micron and Intel, with Chinese suppliers following to remain close to major customers. In consumer electronics, Vietnam has emerged as the regional production hub, attracting 85% of investments in the industry between 2018 to 2024. Major Chinese suppliers of IT equipment to Apple, Samsung, and LG—such as BOE, Goertek, and Luxshare—set up operations at the onset of the US-China trade war and later expanded in 2023 and 2024.

After COVID-19, Chinese investment in intermediary components such as printed circuit boards increased significantly to meet the new demand in consumer electronics, EVs, and semiconductors. In 2024, they represented 72% of newly announced investments in the ICT and electronics sector. Thailand has become a key destination, followed by Malaysia and Vietnam, as Chinese firms position themselves to serve both ASEAN manufacturers and foreign multinationals expanding across Southeast Asia.

Renewable energy equipment

China’s FDI in renewable energy equipment in ASEAN is almost entirely dominated by solar PV and inputs manufacturing. The patterns of China’s FDI in the sectors are deeply intertwined with the global regulatory picture. Chinese firms started “going out” in the mid-2010s, likely as a response to trade defense cases in the US (2011) and the EU (2012-2013) that resulted in high import duties for China-made solar panels. In these early years, Chinese firms piled into Vietnam—which attracted around half of investment value almost every year since 2016, and one-third of count—as well as Malaysia, Cambodia, and Thailand. These four destinations had the proximity and cost-efficient labor skills required to assemble Chinese inputs into final or close-to-final solar PVs for re-export. By the second quarter of 2023, 80% of US PV imports came from these four countries.

The value of China’s solar PV investments in the region jumped in 2020, likely again as a response to US regulatory action. In 2022, the US found certain solar panels made in Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam to be circumventing US AD/CVD duties. While duty collection was suspended for several years by the Biden administration to manage price inflation for panels sold in the US, Chinese firms likely expected duties to resume at some point (they did in November 2024).

Chinese firms responded in three main ways. First, they increased the amount of content produced locally in Cambodia, Malaysia, and Vietnam, including silicon wafers or module covers. Second, they redirected investment and production away from jurisdictions facing steeper or more immediate duties, such as Thailand, toward those with more favorable treatment, notably Vietnam. In 2023, Trina Solar and JA Solar Technologies unveiled plans to invest up to $1 billion in Vietnam to expand their manufacturing capacity. Third, they shifted some production to Indonesia and Laos to avoid anti-circumvention penalties from 2022. We observe a big surge in Chinese FDI in both countries in 2022 and 2023 (Figure 7), especially from smaller Chinese firms, as well as a wave of factory closures or scaling down in Vietnam in 2024. Interestingly, mid-sized Chinese firms with more resources also started investing directly into the US starting in 2022, to hop tariff barriers and take advantage of policies under Inflation Reduction Act. The sharp drop in 2024 might be due to Chinese firms’ domestic difficulties, limiting their outbound FDI capacity but also the expected announcement of new tariffs from the US.

Automotives

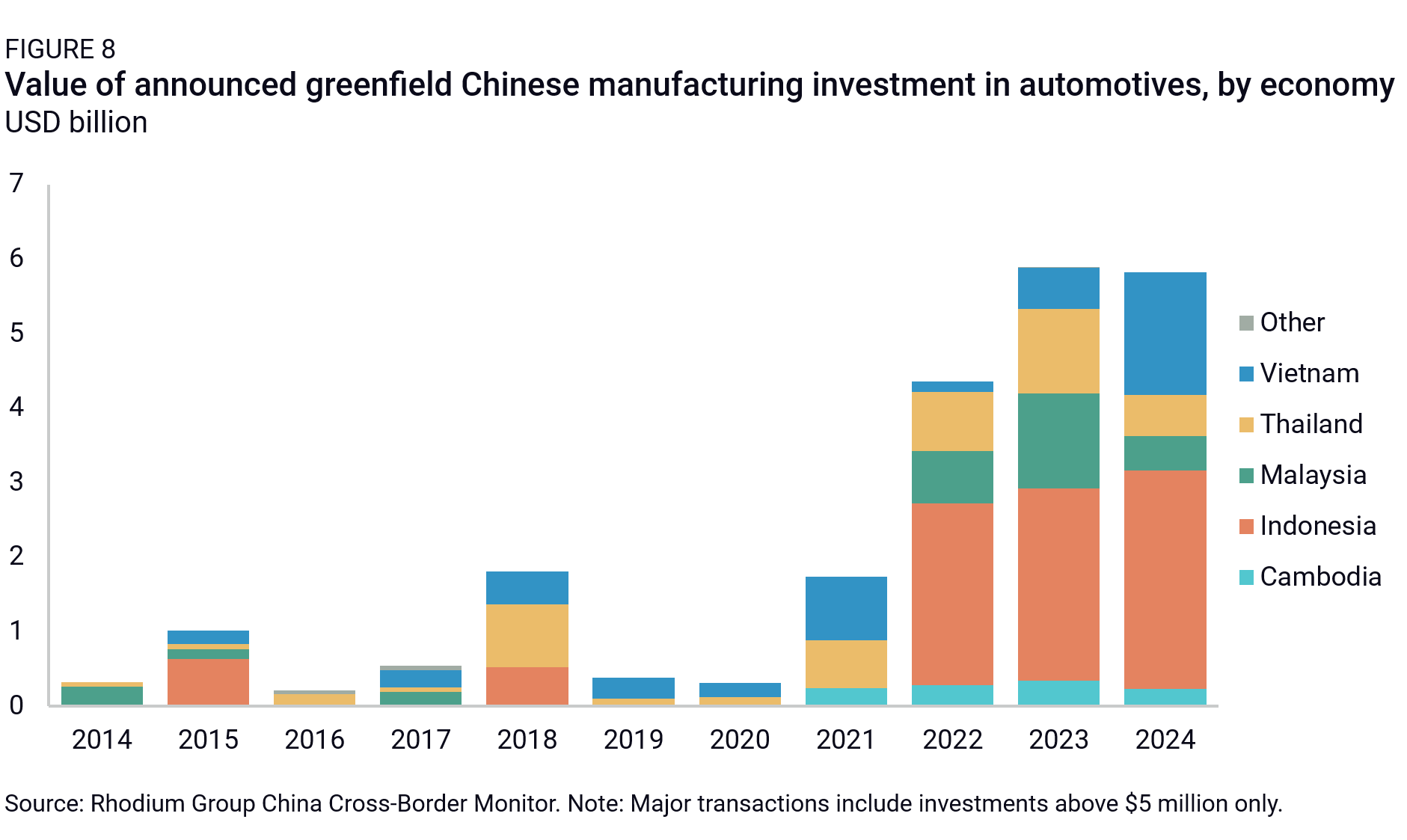

Autos have long featured as a key sector for Chinese FDI in ASEAN in terms of number of transactions, but China’s FDI value has also shot up since 2021 (Figure 8). Most of these investments have taken the form of greenfield projects, except for a few M&A transactions like Geely’s acquisition of a 49.9% stake in Malaysia’s Proton in 2017. They’ve also involved most steps of the supply chain.

Given skills availability and electronics manufacturing capacity, Thailand, Vietnam, and Cambodia have attracted auto part plants, including electronics with PCBs. In contrast, vehicle assembly plants have historically centered across the larger markets of Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam (often driven by SOEs like SAIC or Foton). Since the 2020s, a series of EV manufacturing plants have also been announced in Thailand (an early EV adopter), Indonesia (given consumer base and upstream supply chains in the country), and to a lesser extent, Vietnam. These projects featured private Chinese players like BYD (in Thailand and Indonesia), Chery (in Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand), and Geely (in Vietnam and Malaysia).

The past few years have also seen a spike in battery and battery input manufacturing projects in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. Indonesia’s stringent export policies on critical raw materials—notably nickel, a key input for battery production—have helped drive substantial investment into the country. These measures have catalyzed the development of a more integrated supply chain encompassing raw material processing, battery components, and battery manufacturing. Between 2022 and 2023, nearly half of automotive investment flowed into Indonesia.

Given the nature of the industry (often highly regionalized to better address local market preferences), it is fair to assume that these investments have mostly aimed to serve fast-growing local markets—with a population of over 450 million in just Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam—and nearby ones like Australia. In single instances, however, export ambitions have clearly been at the forefront. SAIC, which has been hit by high EU EV duties, is openly discussing plans to circumvent trade barriers through its Thailand plant. The fact that single plant announcements are getting larger, including multibillion-dollar plants from CATL, BYD, and Chery, could also signal further export potential.

Outlook

US tariffs on China starting in 2017 were one of the core drivers behind the jump in Chinese firms’ manufacturing FDI in ASEAN. Continued and even higher US tariffs on China-made goods can be expected to drive yet more diversification momentum among Chinese firms. Since Trump’s inauguration in 2025, US tariffs on China have increased dramatically, reaching an additional 145% from the early-January level by mid-April. Since then, selective carve-outs have been announced (on a range of electronics products especially), and more might be coming. Regardless, overall tariff levels will likely remain high on China.

From here, three key factors will drive momentum for Chinese FDI in ASEAN. First will be the differential in tariffs between ASEAN and China. If the gap is large, the region will remain a destination of choice for Chinese firms looking to retain access to the US market, given ASEAN’s skills, resources, trade integration with China, and geopolitical alignment in some cases (Cambodia, Laos). However, if bilateral negotiations between the US and Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand fail to reduce reciprocal tariff levels, or if China tariffs are pared down significantly after rounds of negotiations, then Chinese firms will be incentivized to use their China-based production capacity for US and global markets.

Second will be whether the US administration acts on its growing scrutiny of China’s role in ASEAN supply chains. This includes patterns of circumvention and transshipment to the US via the region and high levels of Chinese content embedded in ASEAN exports. If the US demands ASEAN countries decrease Chinese content and linkages in their manufacturing operations, the bar will be much higher for them to remain competitive diversification hubs. After all, Chinese firms and inputs have been critical to ASEAN’s export success, moreso than in other “connector” countries like Mexico.

Recent interactions between the US and Vietnam point in that direction. During his meeting with his Vietnamese counterpart, US Trade Representative Jamieson Greer underlined the need to implement “an effective control mechanism for trade fraud, origin fraud, and illegal transshipment.” Recent reporting suggests Vietnam is offering to tighten its control over transshipment of Chinese goods and diversion of US export-controlled technologies to China to clinch a deal with Washington. The question is whether that offer expands to Chinese inputs and value add in US-bound exports.

Third, Chinese FDI in ASEAN will be shaped by China’s economic performance. The sharp drop in China’s solar FDI to ASEAN in 2024 was likely driven (or at least affected) by the weakness of China’s companies in the sector. More weakness in the automobile or consumer sectors could have similar effects on outbound flows. From China’s perspective, the challenge will also be to keep manufacturing jobs onshore at a time of weak economic growth and rising unemployment. This could trigger much stronger Chinese actions to restrict outbound FDI, as well as people, know-how, and tech flows. Beijing has already taken an active interest in “steering” outbound investment toward favorable countries and prohibiting investments that are perceived as going against the “national interest.” While a major focus so far has been to limit tech transfers, these efforts could soon be extended to sustain domestic jobs and industrial ecosystems.

Footnotes

These countries include Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. We focus here on manufacturing FDI, most directly affected by (and hence a better proxy for measuring the impact of) de-risking policies and firms’ diversification momentum.

ICT and electronics include semiconductors, IT equipment, and other electronics like PCBs.