Back to Ginormous: China’s 2018 Current Account

If this year's estimate is correct, it portends destabilized international financial and monetary regimes, blocked pathways to desperately needed reforms in the US, and stymied chances for poorer nations trying to ascend the development ladder.

Why do policymakers in the US and other major economies continue to raise concerns with Beijing over trade patterns and exchange rates? After all, China’s goods trade surpluses have come down markedly since their mid-2000s highs, and Western economists mostly concur that the renminbi-dollar rate has approached, if not reached, equilibrium value. The reason is that China’s size and growth rate mean that even modest trade and investment distortions have profound implications for the rest of the world. Moreover, improvements in China’s external balance to date have not been locked in with reforms – including a fully flexible exchange rate or bankruptcy proceedings for factories that oversupply the market regardless of demand leading to disruptive surges of exports – which will help ensure that external balance is the norm instead of reliant on heroic political effort. Foreign policy makers have to temper their enthusiasm for improved conditions to date, therefore, with badgering over the need to lock-in China’s rebalancing for the future.

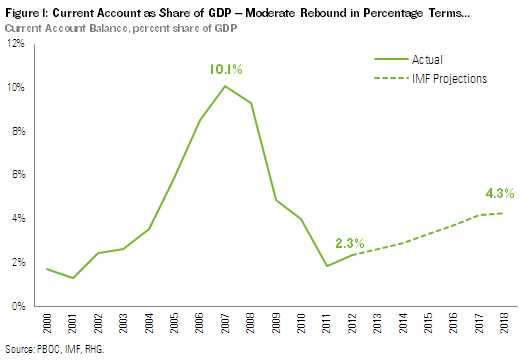

New growth projections from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) clarify how serious these concerns are. The IMF fully revises its World Economic Outlook, or WEO, annually (there is a partial update once a year as well). There has been a robust internal debate at the IMF in recent years over GDP growth projections for China, and for the current account surplus. After the epic surpluses China ran from 2005 to 2010, the Fund was slow to trim their forecasts, even as actual surpluses narrowed in recent years. The WEO projections released at the spring meetings of the IMF and World Bank last week foresee a moderate Chinese current account surplus – defined as under 3% of GDP – through 2014.

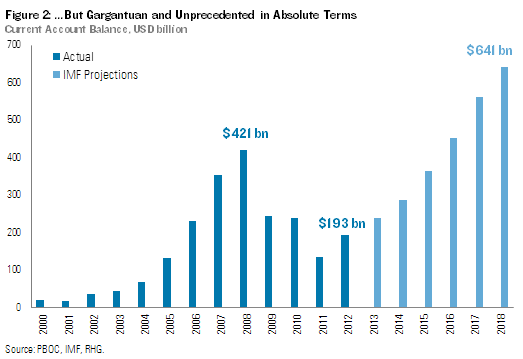

However the medium-term IMF projection is more concerning. The WEO shows China running a 4.3% of GDP current account surplus in 2018, which, at projected growth rates, would mean a nearly $641 billion surplus in five years’ time – tripling from 2012. An even better way to think about the size of that surplus is as a share of world GDP: by that metric China’s surplus more than doubles, from 0.3% to 0.7% of the size of the global economy.

These projections raise a number of concerns. First, while we can debate whether the world can bear those huge external imbalances as a practical matter, the direction of the trend is clearly unacceptable. As China reaches a more mature stage of development it is expected to achieve a more balanced international position, not mushrooming surpluses. If the IMF is even close to right, then not only will China fail to be an engine of growth for the rest of the world, it will in fact be a major negative shock to expectations. Second, if China is running two-thirds of a trillion in annual surplus, somebody needs to accept an equally gargantuan amount of deficit. And who will that be? Europe? The United States? India? Latin American (which is running a large trade deficit with China on the whole)? It’s not clear how major economies stay on a responsible course to recovery while serving as consumers of last resort for a tripling of China’s current account surpluses. Nor is it clear what the impact is for those nations if Beijing has $640 billion a year that needs recycling into Treasury Bonds, shale gas fields and other assets instead of the $200 billion from current account surplus it must presently put to work each year.

Finally, the developmental consequences of swelling Chinese global surpluses for the less advanced economies trying to follow it up the growth ladder are important. If China continues to rely on global demand to fuel its “miracle” even now that it has reached the middle income ranks, what opportunity does that leave for poorer nations to absorb lessons from China’s impressive rise? If China’s surplus as a share of the global economy doubles, even while OECD economies struggle to reduce their net imports in order to honor their debts and pay their bills, then where is the export led growth potential for the Myanmars, Cambodias, Liberias and Egypts of the world?

It is important to recognize that the IMF’s projections have been off before and may well be again. The GDP growth assumptions used to reach 2018 are optimistic, and if China undershoots those levels then the current account percentages will amount to less in real terms. In fact a whole day can usefully be spent grappling with the assumptions in the IMF numbers. Nonetheless, these are the mostly widely employed and stress-tested projections of comparable country growth data for the medium-term that are available. China is intimately involved in the WEO process and has ample opportunity to shape the assessment internally – more and more so, in fact, as time goes by and Beijing’s influence at the Fund increases. The April 2013 WEO projections for China are therefore the starting point for a critical conversation: does Beijing concur with the Fund’s projections, and if not, why not? And if so, how should responsible policymakers on the flip side of China’s burgeoning external surpluses respond? One thing is clear: you don’t have to invent theories of Western hostility or conspiracy to contain China to understand why Washington, Brussels and other partner governments push Beijing so hard over trade and investment-related policy grievances.