Beijing’s 2015 Industry Consolidation Targets: Problem or Solution?

Beijing released policy guidance for consolidating nine “key” industries on January 22, triggering concerns that China is redoubling efforts to boost state-owned enterprises and tighten their grip on the marketplace. The circular, Guiding Opinions on Pushing Forward Enterprise M&A and Reorganization in Key Industries (“Opinions“), was issued by a collection of Chinese bureaucracies under the coordination of China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), hardly a reform-oriented department of Chinese government, and one often in opposition to foreign business organizations in China.

The initial reaction was unease that “consolidation” means more state capitalism and central micro-management of industrial policy — cold water thrown on hopes for a market reform-driven Xi-Li era in Chinese policymaking. That would argue for abandoning bets contingent on strong Chinese growth, since without new reforms China’s economy is sure to stagnate. But hold on: a closer reading reveals this to be a follow-up to an initiative announced years ago. And while China’s industrial planners have long been announcing such roll-ups with limited effects, this round of consolidation talks is more significant for private and foreign firms — but not for the reasons heard so far, and not necessarily in undesirable ways.

Consolidation – Not a New Idea

The industry consolidation initiative outlined in the Opinions originated in an August 2010 State Council circular which tasked administrative planning of consolidation to various government agencies, but lacked any quantitative specificity. The State Council issued a second consolidation circular clarifying some objectives in December 2011.

The Opinions specify quantitative consolidation goals in nine “key” sectors: automotive, steel, cement, shipbuilding, electrolytic aluminum, rare earths, electronics and information, pharmaceuticals, and agriculture — a summary of these goals is provided in Table 1. Successful consolidation, however, depends on other reforms. Local officials won’t relinquish small town SOEs without replacement sources of fiscal support. So in parallel with consolidation talks we see movement on center-local fiscal reform and also central expenditures to support local income growth.

Getting past local resistance to consolidation would be great for private Chinese and foreign firms: it would jumpstart joint venture restructuring, enterprise expansion, cross-border dealmaking and other moves — benefitting China’s consumers, adding to forecast GDP and shaving tail risks. It is no guarantee of further market opening, but it fits into a story of reorientation — which at least raises the prospect of expanding opportunity for non-state firms — better than people think.

Nothing Written in Stone

Given the potential concentration of global market power in firms with questionable corporate governance and non-transparent interactions with a state that is also a market participant, it’s understandable that the reaction to these consolidation plans was sullen. But there are two alternate readings that deserve serious attention by investors and business leaders, readings which could mean more upside opportunity than has been seen for some time.

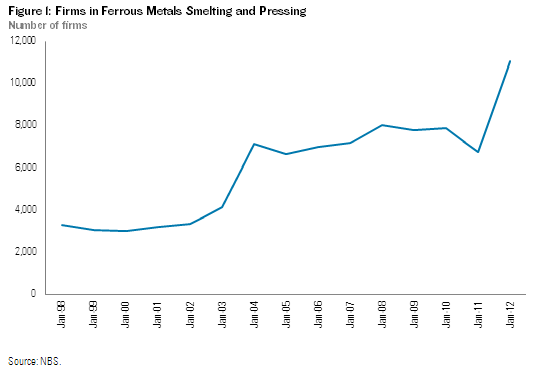

First, China’s central planners have been talking about consolidation for decades, but without an organic market logic backed by pro-competitive reforms, little happens. The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has long wanted to consolidate the steel industry, for instance, to manage energy consumption and create national champions that could better compete abroad. A plan was announced in 2001, but then the number of steel enterprises doubled between 2002 and 2006 as firms saw profits rise and piled in. From a hefty 3,000 ferrous metals firms at the start of the decade, there were 7,000 by 2005, 8,000 by 2010 and — after a brief pullback in 2011 — currently around 11,000 (Figure 1). The top three are world-scale but accounted for only 14 percent of the total production in 2005, while in Japan, South Korea and the United States the top three control well over half the market. China’s steel industry is balkanized, with each province promoting its own local champion, and conditions are similar in other industries. The reasons are deep-seated: so take consolidation plans with a grain of salt.

But second, the forces that defeat Beijing’s consolidation efforts are impediments to private and foreign firms as well. Beijing and General Electric may not share a vision of the endpoint for local competition in China, but they do share the common interim goal of overcoming local protectionism. This local resistance is understandable: sub-national officials are handed social obligations by Beijing but told to fend for themselves to pay for them. Getting promoted from the dog-eat-dog boondocks to respectable higher office depends on finding a way. Therefore local officials rely on tax revenue and other payments from their districts’ state-related firms to foot the bill for their share of highways, healthcare, education, new city halls and countless other things. If you consolidate the steel companies in ten Sichuan counties, you leave nine of them bankrupt and benighted, while crowning one of them a baron.

And that, in a nutshell, is why this is so hard. The January Opinions must be analyzed beyond the industrial-policy and state-capitalism perspectives, and considered in the broader context of China’s local fiscal reforms. To quell local resistance Beijing has to fix the mismatch between revenue and local responsibilities — otherwise, this is all just prattle.

So conversely, if Beijing were serious about addressing the local fiscal problem, it would insist on eliminating local opposition to market rationalization as a trade off. Consider: virtually nothing was more important to unlocking American growth than the interstate commerce clause in Article 1 of the Constitution. Beijing has been fighting intra-provincial localism in earnest since 1984, when policies to legalize internal trade and commerce were modernized. That kicked-off round after round of local schemes to protect home-grown producers over newly mobile sellers from other places. In the same way that Washington overcame state resistance through “fiscal federalism,” this is Beijing’s best hope to create a national marketplace and the economies of scale and scope future growth depends on.

New policy initiatives (the February 6 Income Distribution Blueprint Plan from the State Council) and private discussions suggest that major fiscal reforms are imminent, evidence for consolidation to be taken more seriously. While there are no guarantees, the Opinions are the building blocks of any real reform scenario, and in any case are not antithetical to reforms in any way.

Here’s the Rub

So Beijing’s consolidation intentions don’t have to be bad news. But there are ample reasons to worry about how market restructuring will be handled. The possibility of the process foreclosing the Chinese market to good companies is real, and the stakes of that are gigantic.

Officially the State Council’s notices say that consolidation will be driven by market-oriented alliances and tie-ups (especially vertical mergers) determined through better corporate governance. But given the government’s ongoing regulations and intervention in markets, the absence of a pro-competitive consumer welfare advocate, and the inherent disadvantages for non-state firms in China, it is not clear how this will work. State-owned enterprises dominate some of the “key” sectors, such as steel and shipbuilding, but most include private, foreign and mixed-ownership firms as well. How will Beijing ensure they have equal standing in calculating the public interest (the core of a healthy consolidation process)? The State Council’s December 2011 circular highlighted eleven “key industries” to push forward M&A and reorganization, but the January Opinions left two out — machinery and cosmetics. Experts’ views are that the products in these two industries are too diverse and therefore not high on the priority list for this round of consolidation. That’s fine and well, but this is a reminder that Beijing is not just thinking about consolidation as a general matter, but is tinkering with specific industrial policy ambitions at the same time.

Take for example the treatment of the rare earths industry in the Opinions. The earlier 2011 mandate had called for the top five Chinese producers in the rare earths industry to achieve a domestic production share of 80% by 2015 — and considering that China today produces 95% of global rare earths materials, this would mean profound global market power. The new Opinions, however, leave out the market share goal in favor of a vague call to “significantly reduce the number of miners and refiners.” Experts we spoke to had two views. One camp thought Beijing avoided specifying a precise number so as not to attract foreign criticism in light of the WTO’s July 2012 probe of China’s rare-earth export policies. The other said quantitative objectives are now unnecessary because the remaining large rare-earth export producers will naturally enjoy economies of scale on that level of concentration. For example, the government of Inner Mongolia released a mandate in May 2011 calling for all 35 rare-earth producers in its jurisdiction to merge into a single large one under the state-owned Baotou Steel Rare-Earth Hi-Tech Co., Ltd (Baosteel). But since then the typical local protectionist reactions have reduced the number of consolidatees from 35 to 12, and these signed a framework in December 2012 to transfer 51% of their equity to Baosteel. However, the framework states that if Baosteel is unable to provide a full development plan for the twelve producers within one year (which requires their approval, and hence their local officials!) then the framework “expires”. This is industrial policy machinations 101.

Now, whether the Opinions reflect the intentions of the new Xi-Li leadership, and not just the outgoing Wen Jiabao State Council, is not clear. The Opinions come out in the very final days of the ending political year, prior to the Chinese New Year, in the last month of control by departing deputies. Like policies hustled out in the lame duck phase of any government, these will be subject to more than the usual degree of review by the incoming administration — despite the outgoing team’s assurance of continuity. For now, top level leaders appear unified on industry consolidation. At the December Central Economic Working Conference in Beijing (the annual meeting to coordinate economic development for the next year) both Xi Jinping and Wen Jiabao emphasized fixing industrial sector overcapacity and accelerating the structural adjustment — the main goals of the Opinions.

Not Just About Consolidation

The Opinions deal heavily with industrial policy. The December Economic Working Conference emphasized that large enterprises should drive consolidation by promoting technology and science. Echoing that, the Opinions add to the 2015 concentration ratio targets additional instructions on nurturing large corporations with “core competence” and “international influence.” For example, the automobile industry is to concentrate 90% of output under ten carmakers by 2015, while creating “three to five” large automobile corporations through horizontal and vertical M&A and reorganization. “Three to five” is commonly used in Chinese to indicate a small number when the speaker has no idea what it should exactly be. “Three to five” is used three times in the Opinions to indicate the desirable number of leading enterprises in the automobile, steel and electrolytic aluminum sectors. The vagueness likely derives both from uncertainty and from tactical ambiguity to help manage how much resistance from local vested interest groups is kicked up.

The Opinions also explicitly mandate three of the nine industries — automotive, steel and shipbuilding — to “go out” and “participate in global resource aggregation and management” through overseas mergers and acquisitions. The goal of this series of proposed steps is to keep Chinese companies at the cutting edge of international competition, as explained by MIIT’s engineering director. China’s OFDI outflows have been slow to take off and to this date remain modest compared to China’s position as the world’s top FDI recipient and its role in world trade. Beijing is obviously unsatisfied with the skewed focus on relatively low value-added raw materials investments in its overseas acquisitions basket, and is concerned about challenges it regularly encounters in cross-border mergers and acquisitions because its firms are less of a presence internationally and far less sophisticated.

China’s leadership clearly has the global strength of its producers in mind, not just net national welfare including Chinese consumer interests. The language in the Opinions micro-managing M&A with advice on vertical and horizontal tie-ups makes that clear. As one expert we interviewed insightfully put it: “Vertical mergers are pursued on nationalistic grounds and in a pursuit of giantism, to reduce exposure to external forces and in the name of resource security even though in practice it exposes companies to greater risks in parts of the supply chain that it does not understand and does nothing to reduce the risks of [foreign] embargoes.”

The Opinions also specifically encourages three of the nine sectors — automotive, cement and electronics and information — to extend their business into the service industry and push forward their existing business into more intangible value added activity. That’s more than just a market structure goal, it’s an industry policy objective aimed at getting past the present over-emphasis on industrial production. Moving out of the investment Super-cycle 2000-2010, Beijing has targeted a more sustainable mix of investment, consumption and trade, and this is clearly reflected in the consolidation guidelines.

Conclusion: Work to Be Done, Either Way

There are tens of thousands of Sino-foreign joint ventures with shareholding structures that can’t be rationalized because of local resistance to consolidation or vested interests in industrial policy. This prevents them from stepping up their investment and helping to promote the benefits of competition for a billion Chinese. These and countless other firms will contemplate leaving the comfort — and underperformance — of the status quo if a fair-competition minded consolidation process gets underway. If the consolidation process is unfair, private and foreign firms need to scramble to wind down their presence and recover what assets they can, because holding your ground in these key industries while your rivals grow is an unwinnable game.

Table 1: Specific 2015 targets for the nine key industries

| Industry | Objectives and Targets |

| Automobile | Concentrating 90% of production in top 10 corporations;Cultivating 3 to 5 major automobile corporations with core competency;

Supporting large automobile corporations to extend to service business including R&D, modern logistics, automobile finance, and information service; Conducting cross-border M&A at right timing and developing global production and service network |

| Steel | Concentrating 60% of production in top 10 corporations;Cultivating 3 to 5 major steel corporations with core competency and international impact;

Cultivating 6 to 7 steel corporations with regional influence; Encouraging steel corporations to participate in foreign steel companies’ M&A and reorganization |

| Cement | Concentrating 35% of production in top 10 corporations;Cultivating 3 to 4 corporations with the annual clinker production capacity over 100 million ton, well-developed industrial chains, core competency, and international impact;

Encouraging vertical mergers and integrating businesses in consulting, testing, R&D, engineering and design, installation and project contracting |

| Shipbuilding | Concentrating 70% of production in top 10 corporations;5 corporations entering world top 10 shipbuilding corporations;

Cultivating 5 to 6 major contractors on marine equipment with international influence; Forming strategic alliances via vertical mergers; Promoting leading corporations to conduct overseas M&A |

| Electrolytic Aluminum | Concentrating 90% of production in top 10 corporations;Encouraging collaboration models on “coal – electricity – aluminum” and “mining – smelting – processing – application”;

Cultivating 3 to 5 corporations with international competency |

| Rare Earths | Following the State Council’s guideline for the development of Rare Earths industry in 2011 (issued on May 10, 2011), including industry entry restriction and export control;Significantly reducing the amount of corporations in mining and refining |

| Electronics and Information | Cultivating 5 to 8 corporations with annual sales above RMB 100 billion (USD $16 billion);

Attempting to build corporations with annual sales above RMB 500 billion (USD $83 billion); Developing a number of branded multinationals mastering core technology, strong innovation capability and international competency; Actively extending business from manufacturing to service, pushing the integration of product manufacturing and software/information service, and the integration of manufacturing and operations |

| Pharmaceutical | Concentrating 50% of annual sales in the medicine industry into top 100 corporations;

Concentrating 80% of market share for basic drugs in top 20 companies |

| Agriculture | Following the State Council’s guidelines for the development of Agricultural Industry in 2012 (issued on March 6, 2012);

Encouraging the development of key agricultural corporations which will drive the regional economy |