China Pathfinder: H2 2022 Update

In the second half of 2022, China veered from one extreme to the other, with carefully choreographed control followed by sudden turmoil.

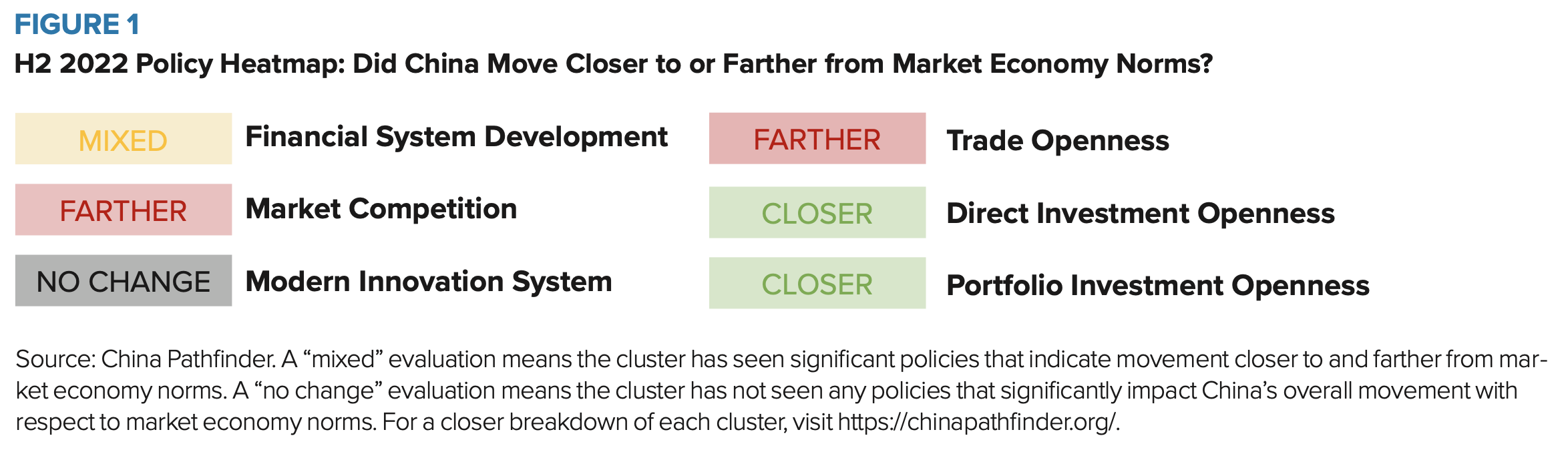

China Pathfinder is a multi-year initiative from the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and Rhodium Group to measure China’s system relative to advanced market economies in six areas: financial system development, market competition, modern innovation system, trade openness, direct investment openness, and portfolio investment openness. To explore our inaugural data visualization and read our annual report and updates, please visit the China Pathfinder site.

In the second half of 2022, China veered from one extreme to the other, with carefully choreographed control followed by sudden turmoil. In October, President Xi Jinping was elevated to an unprecedented third term, underscoring his iron grip on China’s Communist Party and the country. Two months later, the chaotic abandonment of zero-COVID measures, in place for nearly three years, triggered a nationwide health crisis. Throughout, the Chinese government has continued to claim that the path it has chosen for China’s economy and its people is the only right one. Nevertheless, China’s economic weakness is pushing leadership to strike a more business-friendly tone. In recent months, Chinese officials have been reassuring a private sector hammered by regulatory crackdowns and rolling out the welcome mat for foreign investors who have been turned off by years of draconian COVID lockdowns. The defining question of 2023 will be whether the shift in policy and rhetoric is merely a short-term tactic by the Chinese government to shore up growth. So far, evidence of a more meaningful commitment to structural reform is hard to find.

Quarterly Assessment and Outlook

The Bottom Line: In the second half of 2022, Chinese authorities were active in five of the six economic clusters that make up the China Pathfinder analytical framework: financial system development, competition policy, trade, direct investment, and portfolio investment. There were fewer developments in the innovation cluster, though we are watching to see if Beijing can muster a response to profound semiconductor controls imposed by the United States on China in October 2022. In assessing whether China’s economic system moved toward or away from market economy norms in H2, our analysis shows a mixed picture.

A Look at H2 Trendlines

Policy activity in H2 2022 was dominated by measures to offset the economic slowdown and reassure foreign investors. In the investment domain, the Chinese government released a flurry of policies, which ranged from easing rules for foreign bond investors to promoting direct investment in high-tech, manufacturing, and certain service industries. President Xi and Vice Premier Hu Chunhua drove home a similar message, calling for practical measures to attract foreign capital. In a speech to the Central Economic Work Conference (CEWC) in December, President Xi said it was “incorrect” that China had become unfriendly to foreign investment. However, it remains to be seen if the rhetoric will be matched by action. So far, the main positive signal was the announcement by the US Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) that it had received complete access to inspect registered public accounting firms in mainland China and Hong Kong. This development aligns China’s auditing processes for its US-listed companies with US auditing standards, though the PCAOB still has to report the results of its assessment of each company’s accounting practices. The concession by Chinese authorities averted the risk of forced delisting of around 200 Chinese firms from US exchanges, suggesting Chinese leaders are, at least in some ways, trying to limit decoupling.

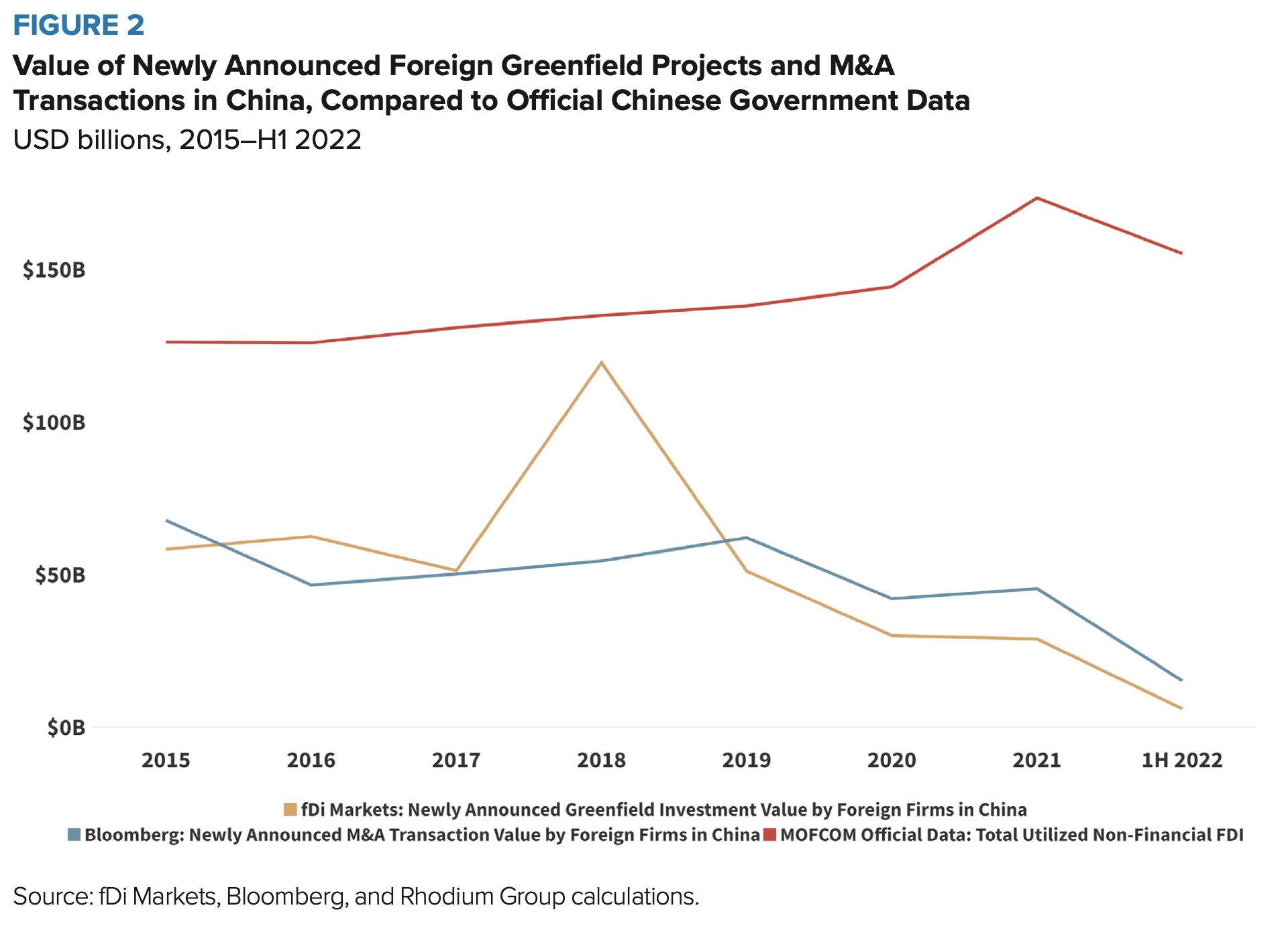

At the same time, the government’s record on data transparency—a key problem for investor confidence—remains dismal. Authorities exaggerated China’s economic strength while suppressing information on the spread of COVID-19. The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) delayed its release of standard economic data— including Q3 gross domestic product (GDP) data—until after the conclusion of the Party Congress, most likely to prevent weak numbers from dampening the positive message the Congress delivered. Chinese authorities grossly underreported COVID-19-related deaths for weeks after scrapping the zero-COVID policy, which led to global criticism and concern from the World Health Organization regarding Lunar New Year travel risks. Only in January did Beijing revise the country’s post-reopening death toll from several dozen to nearly 79,000, which epidemiologists still consider an underestimate. Overly optimistic data extended to foreign direct investment (FDI), where Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) numbers for H1 told a tale of record FDI inflows into China, the opposite of what FDI indi- cators from alternative sources show.

FINANCIAL SYSTEM

In H2 2022, the central bank rolled out limited easing measures to stimulate activity in the bond market and stabilize foreign investor sentiment. In order to increase liquidity and reduce financial stability risks, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) funded around RMB 250 million in corporate bonds for financial institutions through the self-regulatory body of the interbank market, the National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors (NAFMII). In Q4, the central bank also increased its use of the balance sheet as a crisis management tool, which stabilizes borrowing costs and restores confidence. Both measures were motivated by concerns about system solvency, not market liberalization. The bright spot in Beijing’s policies concerning the financial system is the PBOC’s new cash management rules for foreign bond investors. The regulation aims to increase the attractiveness of China’s bond market to over- seas institutions by “partially easing curbs” on the funds and reduc- ing trading costs.

The Chinese government has shifted its posture toward property developers with the intention of achieving a soft landing. The CEWC, while restating that “housing is for living, not speculating,” acknowledged the importance of delivering homes, reducing financing risks for developers, and generating housing demand. The PBOC and China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) rolled out 16 measures to support the property market, which included extensions on developers’ outstanding bank loans and eased restrictions on bank lending to developers. The policy package partly reverses prior measures to reduce moral hazard, risk, and leverage in the property sector. In other words, the overall effect is more pro-stability than pro-market. The government is once again intervening to determine the outcome instead of allowing the market to run its course. However, these measures are still unlikely to prevent property from dragging on the economy in 2023, as banks remain averse to the sector despite relaxed administrative restrictions. The significant slowdown in property sales revenues will continue to limit new construction.

MARKET COMPETITION

While Beijing has wound down sweeping crackdowns on digital platform firms, new elements of regulatory supervision came to bear in the second half of 2022. Although high-level statements emphasized the importance of foreign investment and fair treatment for the private sector, specific policies reinforced state supervision over private companies, especially on the sensitive matter of data security. At a State Council Information Office press conference last November, Wang Song, the information development bureau head of the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), said the internet regulator—which led the crackdown on ride-hailing giant Didi in 2021—is responsible for encouraging and supporting what the government terms the healthy development of inter- net platform enterprises. Wang flagged the importance of platform companies for economic growth and society. Taken together, these are clear signs that Beijing is concerned about restoring economic growth—but its willingness to let the market guide the way to eco- nomic recovery is far from certain.

Despite promises by senior Chinese officials to boost foreign investment, the government took steps to strengthen supervision of foreign firms. The China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) revised rules governing publicly offered securities investment funds, requiring the Chinese subsidiaries of foreign-owned fund managers—such as Fidelity and BlackRock—and foreign Chinese joint ventures to create Communist Party cells. While it is difficult to gauge the impact of individual Party cells, for foreign companies their presence raises the specter of having to consult a Party cadre when making company decisions, heightening the risk of government interference.

Though the regulatory crackdown is winding down, the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) academic resource database did not escape scrutiny, becoming the subject of both an antitrust and a security investigation. The State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) concluded that CNKI, which enjoys a near-monopoly on academic journal access, “abused its dominant market position” by increasing subscription fees and slapped the company with a hefty RMB 87.6 million fine, amounting to 5 percent of its 2021 annual revenue. By comparison, Alibaba and Meituan were only fined 4 percent and 3 percent of their annual revenues, respectively, in previous SAMR investigations. CNKI’s security investigation is potentially more serious, as it addresses the sensitive nature of data access and management. CAC, which carries broad responsibilities for internet and data security, launched a cybersecurity probe into CNKI to “prevent national data security risks, safeguard national security, and protect public interests.” This investigation is ongoing.

Pro-market, business-friendly messages notwithstanding, the government’s commitment to industrial policy is clear. Purchase tax exemptions on new energy vehicles (NEVs) were extended through the end of 2023—the third time such an extension has been granted. Hands-on intervention in 2022 to drive economic recovery in this sector led to twice the number of domestic NEV sales year- on-year, while traditional car sales contracted by 13 percent com- pared to 2021 levels. This comes at a time when the United States, the European Union (EU), and others seek to sustain their own domestic EV industries rather than concede the market to China.

TRADE OPENNESS

Though China took small steps to increase trade openness (including a marginal reduction in tariff rates for some products), trade retaliation against Taiwan for political reasons sent a glaring anti-market signal. In August 2022, then-Speaker of the US House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan, prompting a strong reaction from China. China’s General Administration of Customs responded by banning some Taiwanese food imports, and MOFCOM suspended natural sand exports (used in construc- tion and chip manufacturing) to Taiwan. The economic impact of these measures is negligible, as Taiwan’s agriculture sector makes up a small fraction of its total exports and the annual volume of Chinese sand exports to Taiwan is low. Meanwhile, China’s Taiwan-related trade dispute with Lithuania remains unresolved. In December 2022, China declined the EU’s request for a World Trade Organization dispute panel on Chinese trade measures blocking Lithuanian products and impacting multinational companies that use Lithuanian inputs.

INVESTMENT OPENNESS

The second half of 2022 and beginning of 2023 saw a full-court press by Chinese officials to encourage FDI, especially in strategic sectors. Official data—showing that foreign investment inflows grew by 17.3 percent in the first seven months of 2022—has been used by Chinese officials to rebut assertions by some analysts and multinationals that China is becoming “uninvestable.” The reality, however, is more complex and less encouraging. The “foreign” investment presented in official data is dominated by flows from Hong Kong (a capital control circumvention practice known as “round-tripping”). Micro-level transaction data show that the value of newly announced greenfield FDI projects in China fell to its lowest level in almost 20 years in H1 2022. Data on inbound mergers and acquisitions (M&A) transactions depict a similar trend: from January to July 2022, China recorded only $15 billion worth of inbound M&A, putting it on track for the lowest annual level in more than a decade if the trend holds (Figure 2).

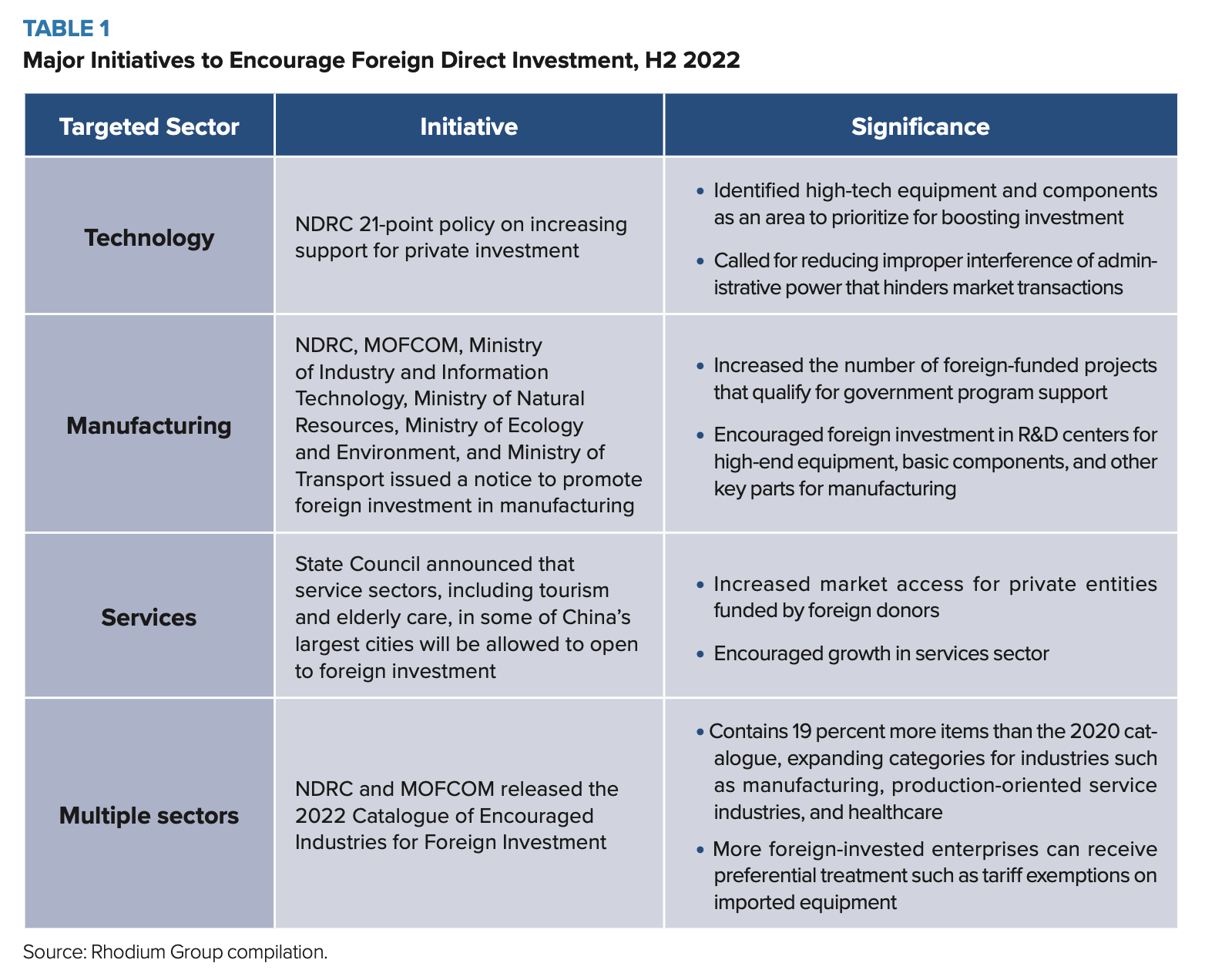

The flurry of policies to encourage investment also belies the upbeat official message (Table 1). The State Council, National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), MOFCOM, and other ministries rolled out policies that targeted high-tech, manufacturing, services, and healthcare industries to boost foreign investment. Investors are debating what to make of these mixed signals.

On the portfolio investment side, an encouraging sign has been Chinese cooperation with the PCAOB to allow inspection of accounting documents after years of intransigence. If this nascent breakthrough holds, it will stabilize investment in Chinese equities, improve accounting transparency, and be generally positive for portfolio investment openness. Separately, China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) expanded the scope of a pilot program it launched four years ago that gives some small tech firms the ability to borrow more from overseas. The CSRC and Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission released a joint announcement to expand the Stock Connect regime to include eligible foreign companies with primary listings in Hong Kong and additional shares listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges. The move will increase the scope of eligible stocks—enabling foreign investors to diversify their portfolios—and is also favorable for foreign companies in China.

Special Topic: The Chaotic Start to China’s Post-COVID Era

What kind of China will emerge in the next year? Years of COVID containment measures have taken a toll on economic dynamism, and the case for reenergizing economic reforms has never been more compelling. But obstacles remain. Officials continue to highlight the superiority of China’s state-driven economic model, while foreign partners view promises of further opening with necessary skepticism.

The end of zero-COVID restrictions and the resumption of travel and services sector activities for Lunar New Year will bring about an improvement in China’s economy—especially the consumer-facing segments—in the first half of 2023. However, an end to zero-COVID does nothing to remedy long-running structural problems. Distress in the property sector, lingering unemployment for new graduates, and weaker hiring in sectors that previously generated significant economic growth all stand in the way of a rebound.

The abrupt end of China’s zero-COVID policy left observers puzzling over the haphazard pivot. The policy was in place for nearly three years, during which resources went more to mass testing and lockdowns than investing in strengthening the healthcare system’s capacity and providing vaccines and antiviral medications in advance. The lack of preparedness by leaders, who usually tout their competence and control, did little to revive the sentiment for Chinese citizens and foreign businesses already suffering from China’s economic slowdown. China’s continued refusal to import foreign mRNA vaccines is evidence that ideology and nationalism remain in command. The opaque zero-COVID aftermath—particularly the absence of credible reporting on infections and deaths— brought uncomfortable comparisons to the start of the pandemic, when the government prioritized stability over transparency.

China needs to reestablish “two confidences” to restart the economy. The year 2023 is set to test China’s willingness to take a market reform path. Beijing will have to rebuild confidence with not only foreign investors but also domestic consumers and businesses, all of which must have a place in a sustainable, consumption-driven growth model. The effort to win back foreign investors is in full swing, with Vice Premier Liu He issuing a promise at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos in January 2023 that “China’s door to the outside will only open wider.” The strategy for convincing domestic consumers and businesses to remain confident is less clear.

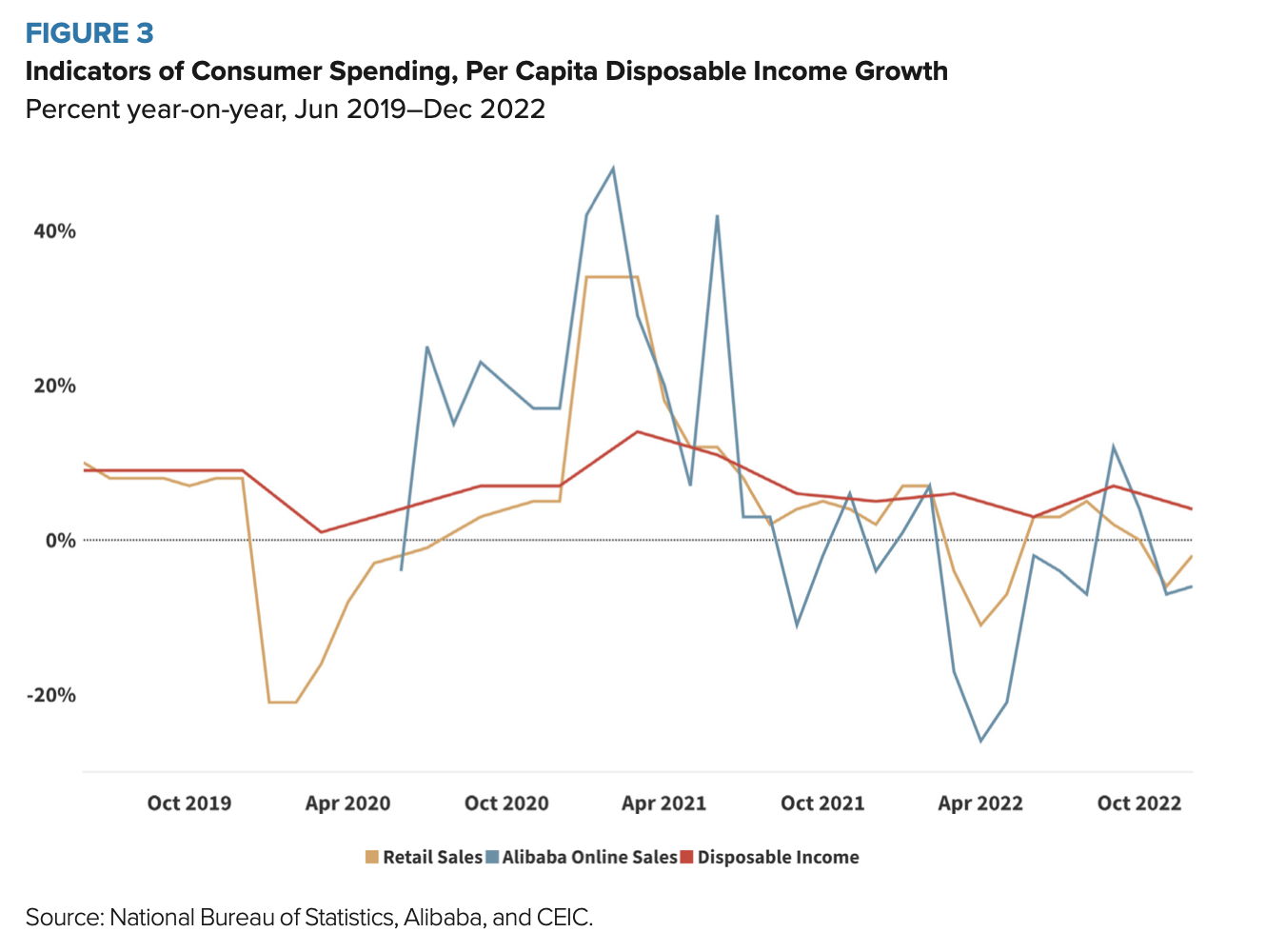

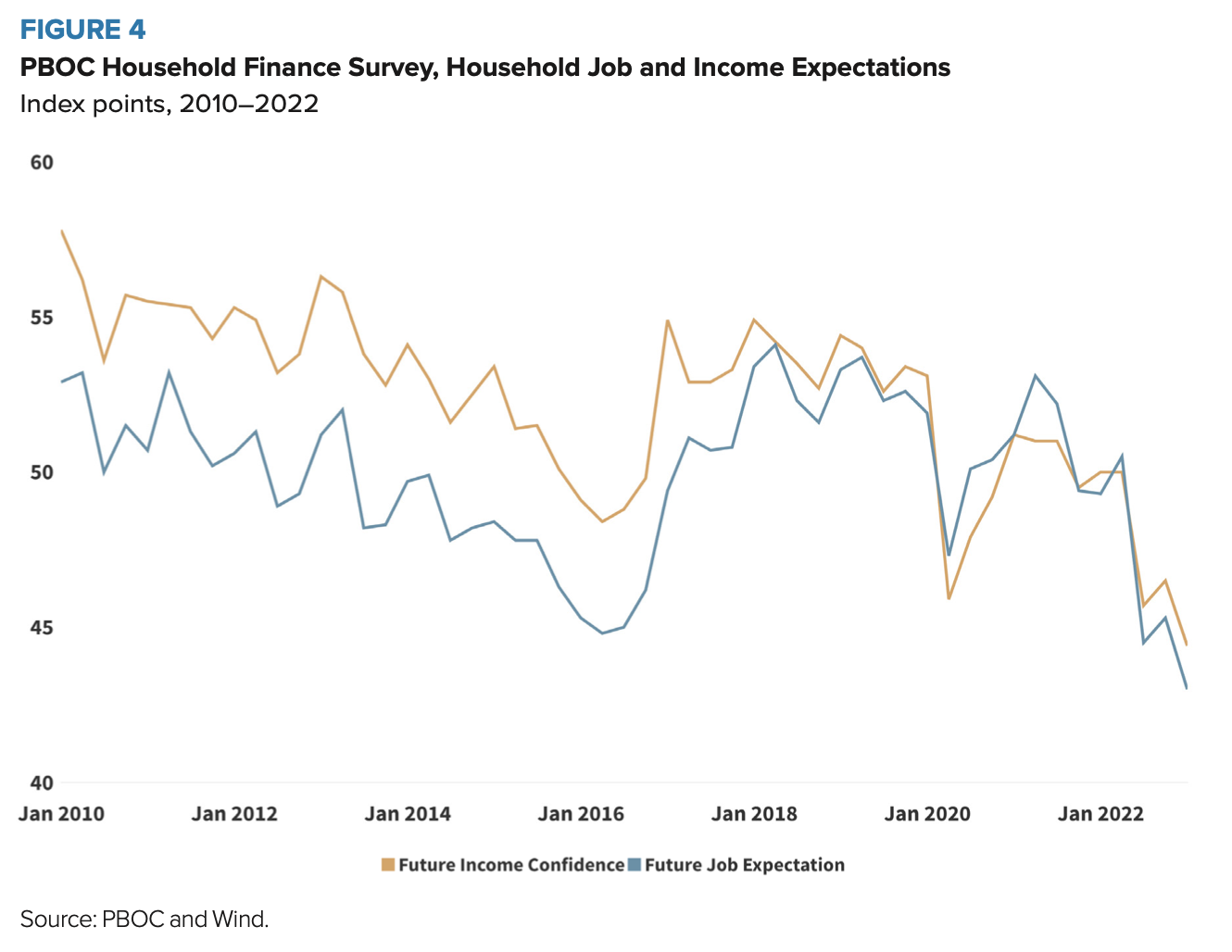

For Chinese households, housing is the greatest store of wealth, so the deteriorating property sector leaves them feeling poorer and less inclined to spend. Together with slow disposable income growth and high youth unemployment, these factors all weigh on consumer confidence, which is near an all-time low. Household spending was disrupted by lockdowns throughout 2022 and then by the spread of the virus itself after controls were jettisoned in the fourth quarter of 2022. Per-capita disposable income grew only 2.9 percent for the full year, the slowest rate since 2013 other than 2020 (Figure 3). Growth in retail sales ended 2022 in the red, with a 1.8 percent contraction in the fourth quarter. Online shopping, which has been less affected by lockdowns, has reported even greater declines: Alibaba’s Taobao and Tmall sales, representing around 17 percent of total retail sales, decreased by 6.2 percent last year. The latest household survey conducted by the PBOC in December 2022 shows a sharp drop-off in expectations for employment and income growth, with confidence indicators falling to their lowest in a decade or more (Figure 4). The survey even included responses submitted after the government rolled out supportive measures for the property sector and eased COVID restrictions.

Lack of worker confidence remains a persistent problem. Youth unemployment (ages 16–24) rates improved, declining to 16.7 per- cent in December 2022, but this is still far higher than the five-year average of 13.7 percent. The abrupt end of zero-COVID exacerbated the unemployment problem for workers who had found job stability in the “COVID economy”: test kit manufacturing, implementation of lockdowns, and virus-related surveillance. Once considered essential to China’s economy and the on-the-ground execution of government priorities, many have not received their wages and have been subject to sudden layoffs.

Although H2 2022 was not short of signals that the government’s focus is shifting from political to economic priorities, these “green shoots” will wither without follow-through. While the government announced foreign investment opening measures, these moves targeted specific sectors handpicked according to industrial policy priorities. The government has relaxed its grip on the private sector in some ways, but is not letting go entirely. Pro-market signals competed with the new requirement for foreign-owned fund managers to have Party cells, initial public offering (IPO) fast-tracks for companies in strategic sectors, and the government’s acquisition of “golden shares” in units of Alibaba and Tencent. Such “golden shares,” typically a 1-percent stake, allow government-controlled entities to gain disproportionate power over corporate decision-making, such as a seat on the board. A wholehearted embrace of market reforms it is not.

Solving its domestic problems is only half the battle—China also needs to address strained ties with other major economies to ensure a sustainable, long-term recovery. This explains the recent global glad-handing campaign by China’s senior leaders. Starting in late 2022, President Xi met with President Biden at the G20 summit in Bali and Vice President Harris in Bangkok; Vice Premier Liu He met with US Treasury Secretary Yellen in Zurich; and US Secretary of State Blinken was supposed to meet with Minister Qin Gang in China in February, before the meeting got postponed over the spy balloon incident. The uptick in engagement, coming after China had further downgraded dialogue following Speaker Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan last August, signaled the importance China’s leaders place on relations with the United States. The EU also received strong positive signals about China’s eagerness to reengage, notably from Fu Cong, Beijing’s new ambassador to the EU.

The charm offensive comes against the backdrop of accelerating steps by the G7 powers to limit Chinese access to critical technologies, with additional semiconductor export controls introduced by the United States in October 2022 marking a potent move among the recent spate of regulatory maneuvers. China is keen to reduce tensions, and its “Wolf Warrior Diplomacy” seems to have run its course. This incipient trend is conducive to a more cooperative environment but is far from sufficient. The hard work all lies ahead, starting with a credible commitment to move forward with structural reforms announced a decade ago but no closer to completion.