China Pathfinder: Q1 2022 Update

China’s leaders spent the first months of 2022 in damage-control mode, as a host of economic problems and new pandemic-related challenges piled up. With the entire city of Shanghai under a zero-COVID lockdown, the crackdown on technology firms ongoing, and the property sector deteriorating, good economic news was scarce.

China Pathfinder is a multi-year initiative from the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and Rhodium Group to measure China’s system relative to advanced market economies in six areas: financial system development, market competition, modern innovation system, trade openness, direct investment openness, and portfolio investment openness. To explore our inaugural data visualization and read our annual report and updates, please visit the China Pathfinder site.

China’s leaders spent the first months of 2022 in damage-control mode, as a host of economic problems and new pandemic-related challenges piled up. With the entire city of Shanghai under a zero-COVID lockdown, the crackdown on technology firms ongoing, and the property sector deteriorating, good economic news was scarce. The lockdowns alone—not considering the less dire zero-COVID measures—have affected more than 25 percent of China’s population, hitting consumption and manufacturing across the country and triggering a broad public outcry. On the geopolitical front, Beijing’s ambiguous positioning on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine raised the prospect of secondary sanctions, amplifying the risk calculations for foreign businesses in China. Foreign capital, meanwhile, has been flowing out of China amid a mounting debate about whether the country is becoming “uninvestable.” With the 20th Communist Party Congress scheduled for November, China’s leadership will be firmly focused on ensuring stability and growth this year, pushing reform down its list of priorities.

Quarterly Assessment and Outlook

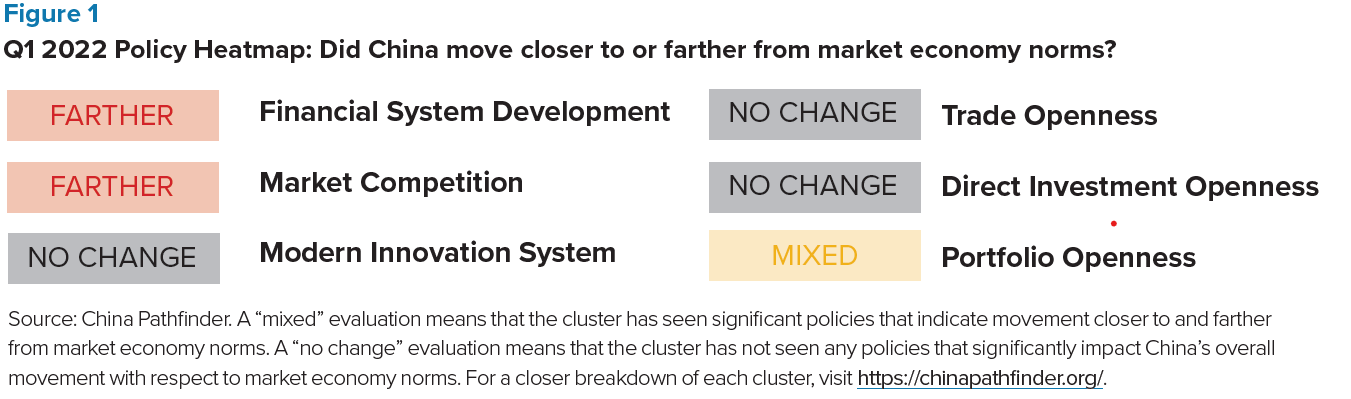

The Bottom Line: In the first quarter of 2022, Chinese authorities were active in three of the six economic clusters that make up the China Pathfinder analytical framework: financial system development, competition policy, and portfolio investment openness. There were fewer developments in the innovation, trade, and direct investment clusters. In assessing whether China’s economic system moved toward or away from market economy norms in this quarter, our analysis shows a distinctly negative shift.

Figure 1 reflects the direction of China’s policy activity in the domestic financial system, market competition, and innovation system, as well as policies that impact trade, direct investment, and portfolio investment openness. This heatmap is derived from in-house policy tracking that weighs and evaluates the impact of Chinese policies in Q1. Actions are evaluated based on their systemic importance to China’s development path toward or away from market economy norms. The assessment of a policy’s importance incorporates top-level political signaling with regard to the government’s priorities, the authority of the issuing and implementing bodies in the Chinese government hierarchy, and the impact of the policy on China’s economy.

A Look at Q1 Trendlines

State intervention to shape market outcomes and boost growth defined policymaking in Q1 2022. In March, China’s leaders met for the so-called “Two Sessions”—important annual meetings where policy priorities are set for the coming year. The Government Work Report for 2022 sent conflicting signals: an aggressive target for gross domestic product (GDP) growth of “around 5.5 percent,” but only modest measures to support this target. The Chinese government insists that growth must be strong this year, but the prospect of delivering on this aim is fading with COVID lockdowns impacting the most important cities in the nation, and household demand and factory supplies curtailed.

Financial System

Beijing backpedals on holding real estate developers accountable but increases controls on how capital is allocated. Financial system policy centered on at-risk real estate firms this quarter. Overall, Beijing is not providing significant concrete support for property developers, but is using heavy-handed interventions to try to prevent a credit crunch in the sector. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) and China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) encouraged Chinese asset management companies (AMCs), such as China Huarong Asset Management Co., to support troubled real estate developers by absorbing bad loans and taking over suspended projects. The PBOC issued window guidance (an unofficial method to align banks with the government’s lending growth targets) to prevent banks from calling in their property developer loans.

The 2022 Government Work Report stated that the PBOC, CBIRC, and Ministry of Finance may take financial stability promotion to new heights by raising several hundred billion renminbi (RMB) for a fund to bail out financial institutions. These policies exacerbate the moral hazard in China’s real estate sector in numerous ways: they encourage AMCs to engage in transactions with risky developers that are unlikely to be profitable; incentivize large developers to add leverage; and ensure limited liability from high-risk lending practices. The property mess has been a long time coming, but this year, temporary fixes will take precedence over meaningful steps to tackle problems in the sector because political priorities come first.

Elsewhere in the financial system, CBIRC announced it would set up a “traffic light” system for investment. Though the announcement was light on details (beyond promising to strengthen oversight of high-leverage and monopolistic behavior), related government messaging provides additional context. This marks the latest step in the government’s campaign on capital expansion in select sectors or, as the People’s Daily described it, the “disorderly expansion and barbaric growth of capital.” In the same piece, the People’s Daily said the goal of managing capital was to “guide and urge companies to obey the party’s leadership.” Investors are unlikely to welcome another attempt by the government to tell them where they should put their money. Certainly, Beijing’s tolerance for over-investment in property does not inspire confidence.

Market Competition

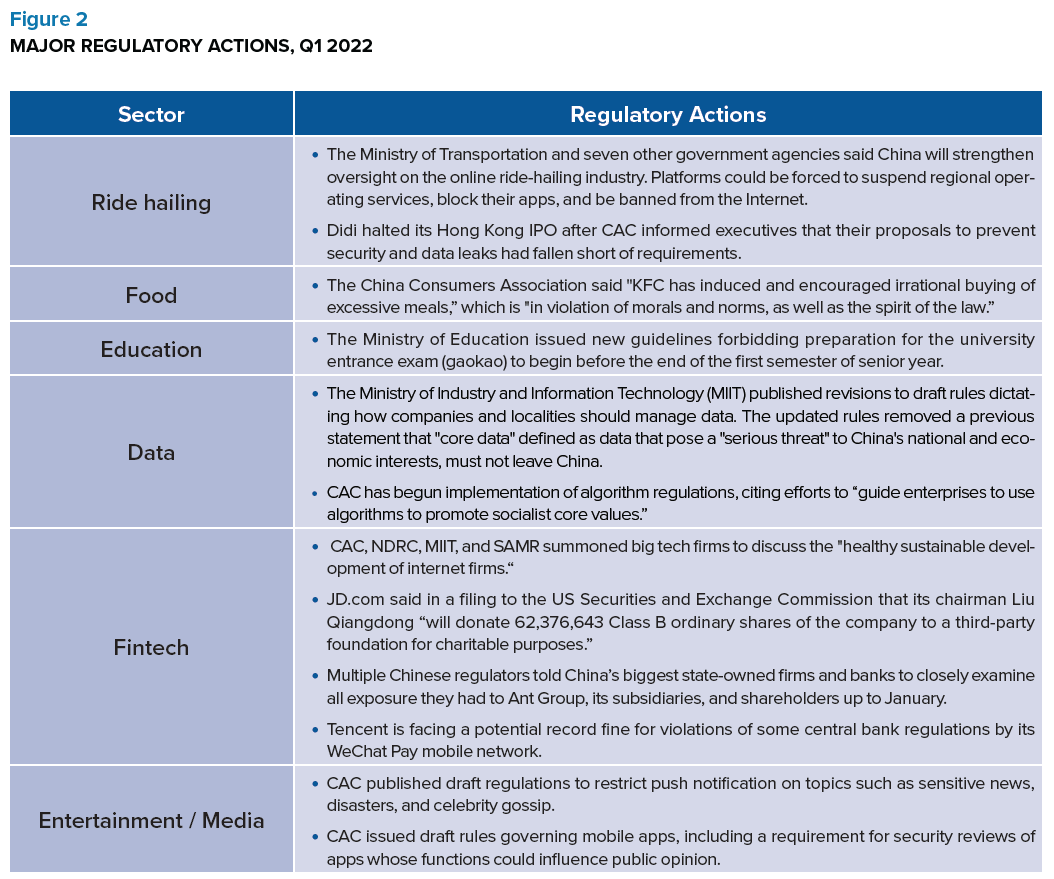

The tech crackdown, which accelerated in the summer of 2021, continued in Q1 2022 with the state’s increased scrutiny on China’s innovative industries (Figure 2). The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), which has emerged as a super-regulator over the course of the crackdown, summoned various tech chief executive officers (CEOs) in January to lecture them on the importance of following state guidance. According to the CAC, CEOs raved about the session and agreed to be more cognizant of their social responsibility. An example of the growing influence of regulators in the business decisions of private companies was Tencent’s announcement in Q1 2022 that it would reorganize its film unit to produce more patriotic content instead of Hollywood blockbusters. Companies are increasingly unsure about how to follow Beijing’s ideological guidance while simultaneously achieving market-driven results.

The CAC also began implementing new regulations that steer enterprises toward using algorithms to “promote socialist core values,” increase the spread of “positive energy,” and effectively deal with “illegal and bad information.” How to deal with algorithms and their pervasive influence on social discourse is an ongoing conversation worldwide. In the Chinese context, however, this new wave of regulation coincides with the tech crackdown and tightening state control over how firms and individuals share information.

The only development in the tech regulatory space that can be seen as a bright spot was on the data front: the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) revised draft rules issued in Q4 2021 on corporate data security, removing an outright ban on exporting “core data.” While the regulations still leave the government in control of data rules, the revision points to a less restrictive approach. Even so, the real impact will depend on how the regulations are implemented.

China’s small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), chronically starved for capital, received another boost from the government, which may have a positive impact on market competition. SMEs have been hit particularly hard by disruptions to the economy resulting from structural problems and COVID outbreaks. Based on anecdotal reports of SME failures and data showing deeply negative new business registrations, the outlook for healthy market competition could be badly impaired by myriad business failures. To alleviate these risks and support SMEs through the current tempest, China—like countries throughout the world during COVID—has sweetened emergency measures to help enterprises. The 2022 Government Work Report included plans for a tax cut and tax rebate in 2022, amounting to 2.5 trillion RMB. The tax reduction supports manufacturing, small and low-profit enterprises, and self-employed businesses. The report includes a temporary provision for small-scale taxpayers to be exempted from value-added tax (VAT). These measures should promote cash flow to small businesses and encourage investment. This policy is both pro-growth and pro-market, as it reduces market distortions and enables small firms to compete on a more even playing field.

Openness to Investment

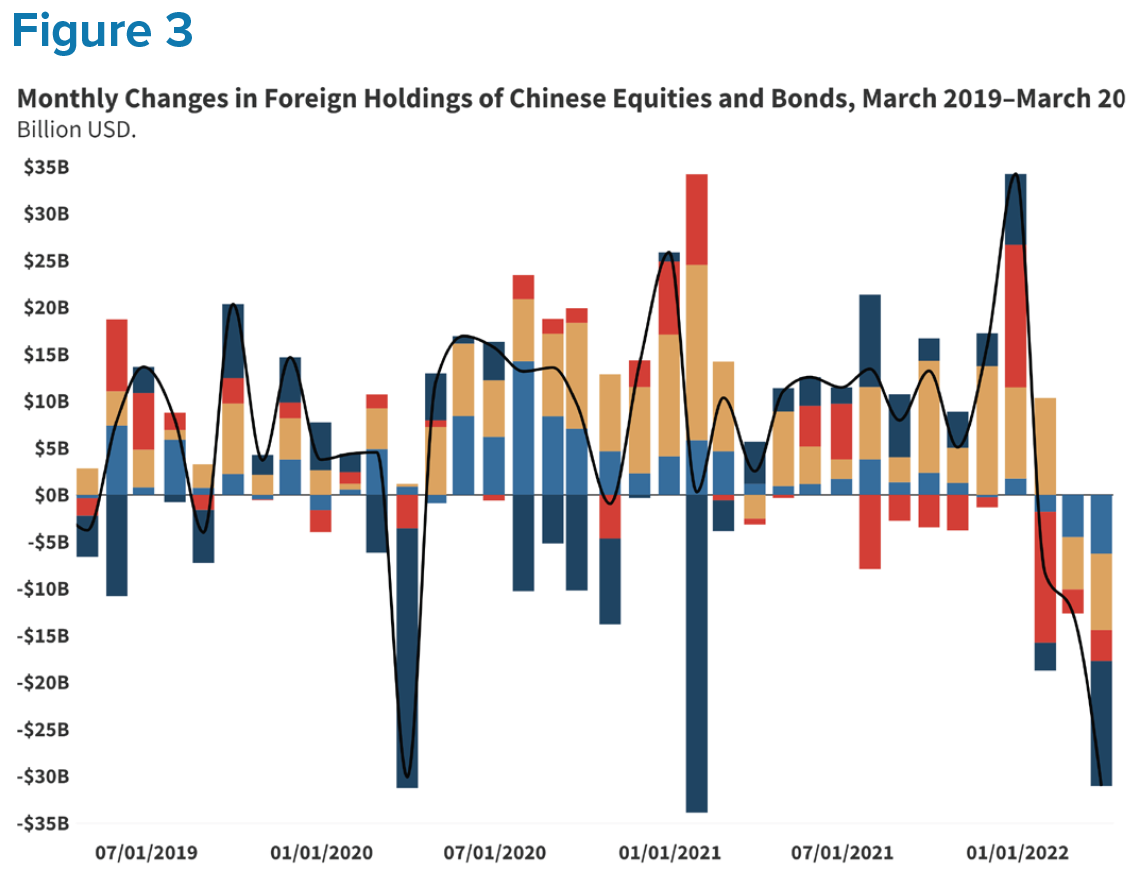

This quarter has seen major shifts in the portfolio investment space, with investor confidence in China declining. After net inflows totaled a record $138 billion in 2021, portfolio outflows surged in Q1 2022: Net holdings of onshore bonds and equities fell by $36 billion and $16 billion, respectively, in the quarter (Figure 3). Though narrowing US-China yield spreads were a big factor, other drivers of these outflows included concerns over the tech crackdown, falling GDP growth expectations, and growing political risks tied to China’s stance on Russia.

Long-term investors have based their bullish China bets on Beijing’s commitment to a gradual liberalization of finance. Recent signals have offered reasons to doubt that commitment, and these “passive” investors are now rethinking their assumptions. To be sure, there have also been some inflows recently, but these were mostly short-term in nature. With interest rate spreads between China and the United States closing quickly as Washington raises rates, we are seeing a reversal of flows for investments of less than one year in duration.

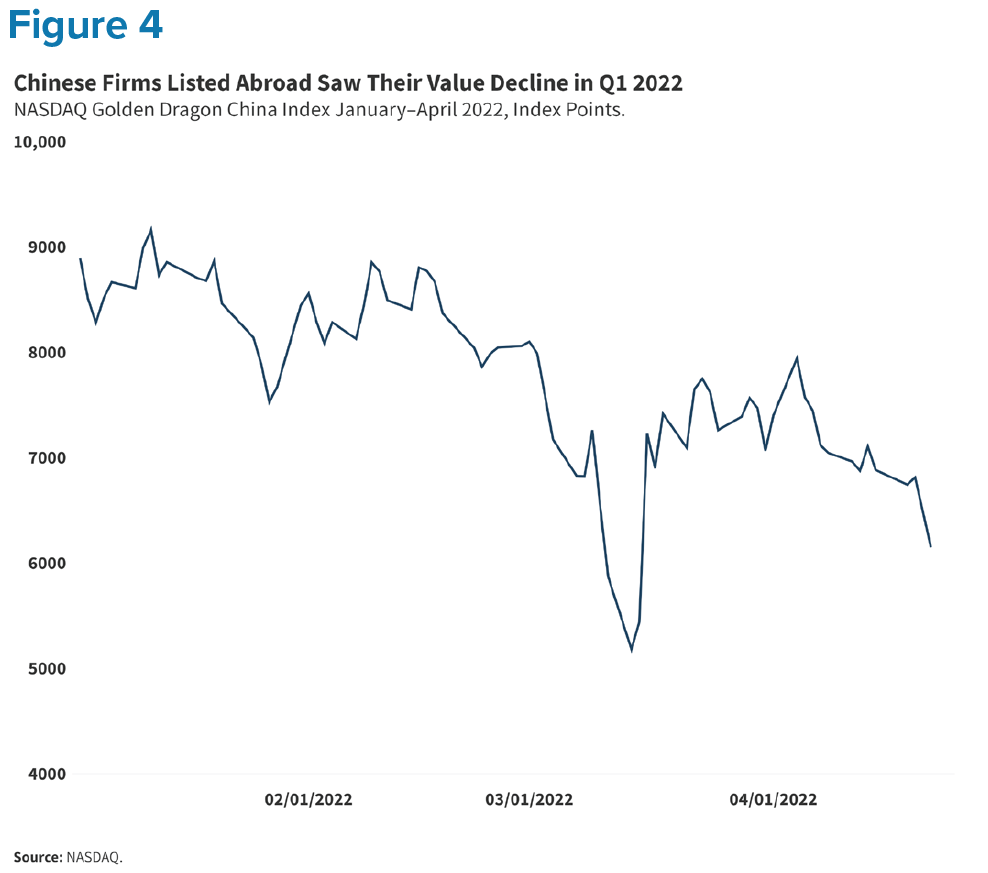

US-listed Chinese firms saw their shares decline steeply over the span of a few months (Figure 4) amid long-simmering questions about access to auditing information and indications that firms could be delisted as early as 2024 under the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act. At the time of publication, the SEC has provisionally identified 128 companies as at risk of being delisted, and the list is evolving. The China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) went so far as to modify a decade-old rule restricting the sharing of financial data by offshore-listed firms. Throughout the quarter, Chinese regulators talked up the prospect of a breakthrough with US regulators, although there has not been a positive outcome yet. While the rule modification is a positive step, the core conflict has yet to be resolved, as the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) has insisted on nothing less than full access to audit information for all listed firms.

Special Topic: The Improbable 5.5 Percent Growth Target

At 5.5 percent, the Chinese government’s GDP growth target for 2022 was seen as a stretch even before a new round of COVID-related lockdowns was imposed in the waning days of Q1. Beijing’s subsequent insistence on upholding the target suggests that political objectives will trump reform priorities in the run-up to the Communist Party Congress in late 2022. China’s ambiguous stance on the Russian invasion of Ukraine—voicing support for an end to the conflict, yet blaming NATO for it—has added to the geopolitical risks surrounding China’s growth outlook.

Real Estate: No Easy Reset

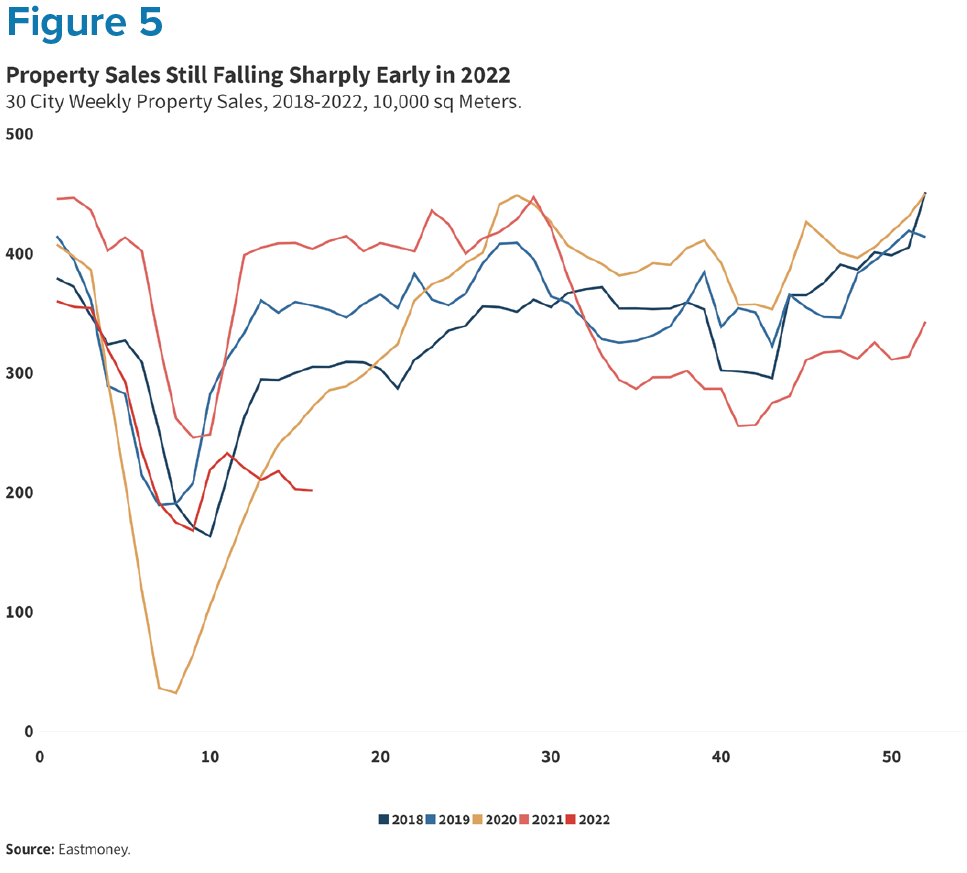

Property is by far the most important sector in China—representing up to a quarter of the country’s GDP. At the end of Q1 2022, all indicators pointed to a meaningful contraction in residential construction activity and sales (Figure 5), with numerous private developers in or at risk of default. In 2021, total property sales amounted to 18.2 trillion RMB, or 16 percent of GDP. With housing prices and sales volumes in decline, developers must prepare for a 2 trillion RMB reduction in annualized sales revenue. The sales decline is more than four times as large as China’s last market correction in 2014–2015. Even with the decision on April 27 to turbocharge infrastructure investment, it is unlikely that we will see growth in overall investment levels in 2022 given the ongoing weakness in the property sector.

Tech Crackdown: No End in Sight

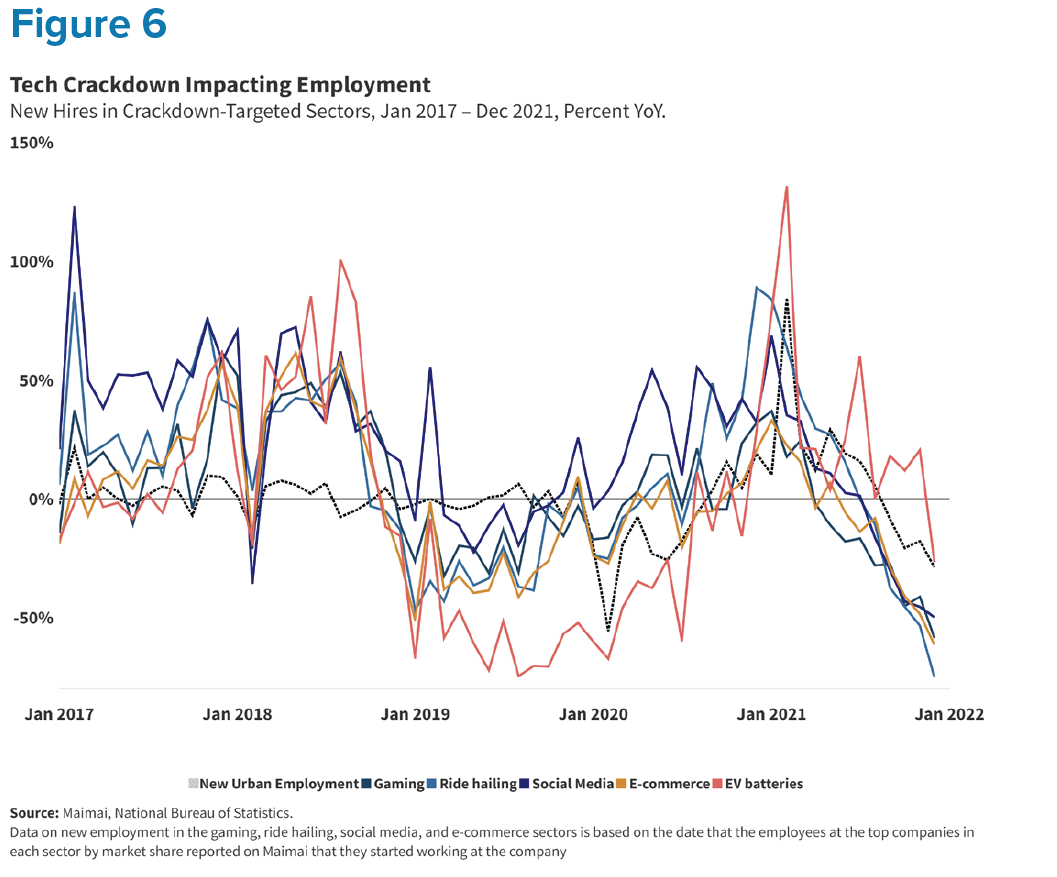

The costs of Beijing’s tech crackdown go beyond reduced valuations: employment and new business formation have also taken a hit. Employment data scraped from Maimai, a job networking platform, shows steep declines in new hiring in the sectors targeted by the crackdown (gaming, ride-hailing, social media, and e-commerce) starting in July 2021 (Figure 6). Hiring in these sectors fell at a greater rate than the steep 8.2 percent year-on-year decline seen in the overall economy in the second half of 2021. In previous economic downturns, ride-hailing and other gig economy sectors absorbed displaced workers. This is no longer the case.

Despite efforts to support “hard-tech” industries, hiring, and business formation are showing mixed results in these sectors as well. One might hope that tightening measures in education and e-commerce would free up capital and labor for more strategic sectors like robotics or biotechnology. But, based on some business formation indicators, hard-tech sectors have not offset the lackluster growth in sectors directly affected by the crackdown. The continuing regulatory crackdown is dragging growth down further at a time when confidence is already strained. Regulatory goals are hindering the vitality of certain sectors and undermining China’s ability to meet its growth objectives.

Zero-COVID Lockdowns: Is There a Breaking Point?

In Q1 2022, 45 Chinese cities—including Xi’an, Tangshan, Dongguan and, critically, economic powerhouses Shenzhen and Shanghai—faced lockdowns due to COVID-19 outbreaks. In the major cities alone, around 97 million people had endured in-home lockdowns by the end of March. The response to the outbreak is now the most significant drag on the economy, with “dynamic clearing” hitting consumption. Official GDP statistics for Q1 suggest the economy performed well—an assessment that strains credulity.

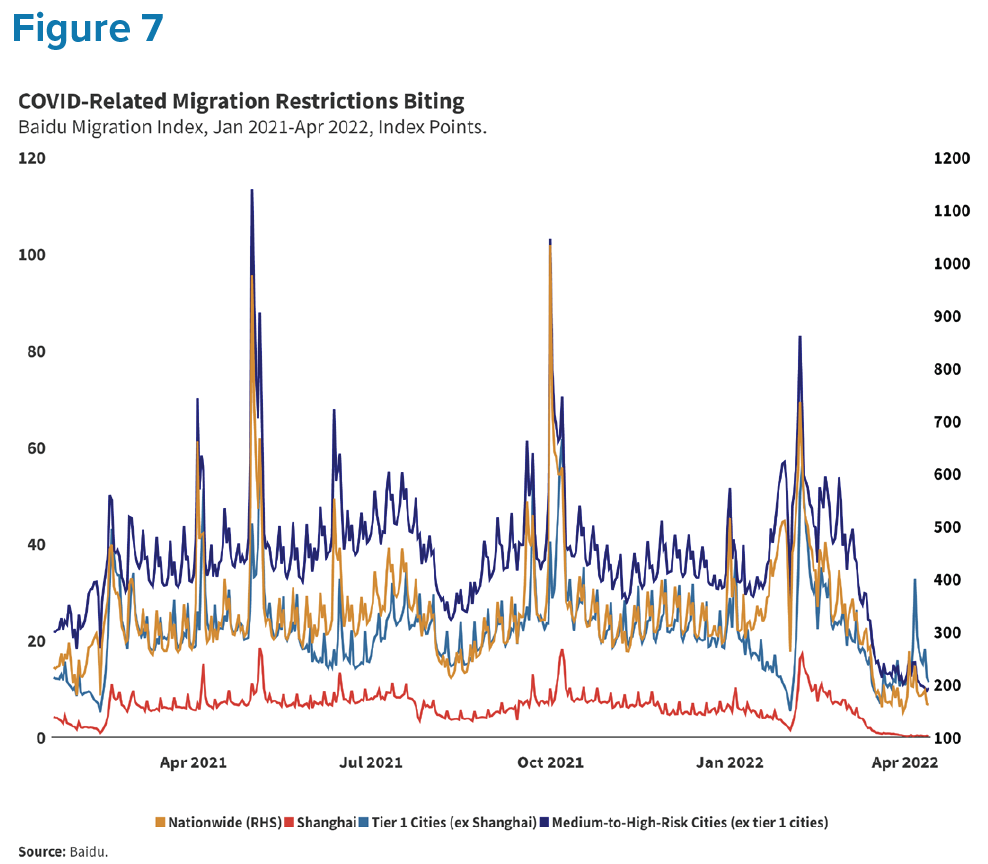

Economists at the Chinese University of Hong Kong estimate that lockdowns will cost China at least $46 billion per month in lost output, the equivalent of 3.1 percent of GDP. While the Government Work Report pledged to promote a consumption recovery, the zero-COVID policy is making that impossible. The Baidu migration index (Figure 7) shows that restrictions are preventing the domestic movement of people for work and travel. This undermines services sector activity, household earnings, factory output, and consumption spending.

Looking Ahead

The government’s upbeat growth story is being sorely tested by economic realities on the ground. Despite significant headwinds, including the property sector contraction and lockdowns, China reported an improbable 4.8 percent growth rate for Q1 2022. This has raised questions about the credibility of China’s data among observers in the country and beyond. After the data release, the International Monetary Fund, banks, and private analysts cut their own China growth forecasts.

Lockdowns will raise economic costs in the months ahead. The Shanghai government’s inability to manage a citywide lockdown sent economic and political shockwaves across the country. Hoarding is taking place in preparation for future lockdowns, adding to food inflation and aggravating supply chain stress. Xi’an and Shanghai officials were put in a nearly impossible situation by the leadership in Beijing, and their struggles, in turn, will make it harder for authorities in other cities to maintain public confidence. As the broader Chinese public has witnessed the extremity of these lockdowns, fears of a repeat situation will send residents scrambling to escape in advance. Even if Shanghai’s outbreak comes under control, future outbreaks will be far more difficult to control.

With growth decelerating and fewer attractive policy options available to China’s authorities, might Beijing be tempted to reopen the reform debate? Our expectation is that policy flexibility will remain limited in the run-up to the Communist Party Congress in November. But, the worse the economy gets, the greater the need for China’s leaders to adjust their course.