China’s Fiscal and Tax Reforms: A Critical Move on the Chessboard

On June 30th China’s top leaders endorsed broad reforms to the nation’s tax system and center-local fiscal dynamics, and, critically, set out a near-term 2016 deadline for completing substantial reforms to ensure that the longer-term reform agenda has a chance to be complete by 2020. Tax and center-local reforms are the thorniest and most fundamental elements of a true overhaul of China’s economic system, so while this move in no way assures reform success, it is a powerful indicator of intent and timing. This move enhances the possibility of sincere market reforms in the medium-term. In this brief analysis we review the context of these reforms, discuss the renewed tasks and objectives, and contemplate the implications of this interim reform deadline.

1994 reforms

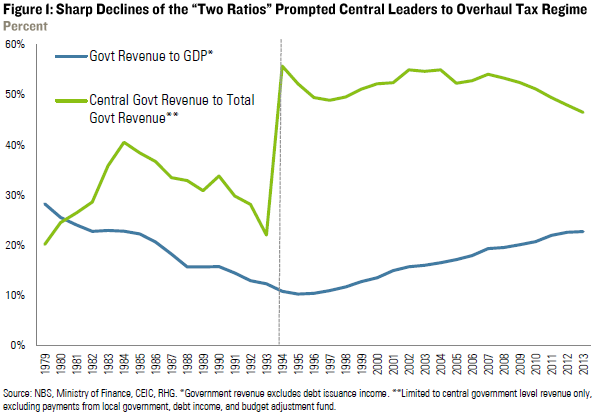

The foundations of China’s current center-local fiscal system were laid in 1994, when then premier Zhu Rongji engineered a substantial overhaul of the country’s fiscal and taxation regime to consolidate government control over the economy. Prior to the 1994 fiscal and tax reforms, Beijing would negotiate with local governments over the share of locally collected taxes that would be paid into the central budget. For some provinces the share was fixed at a certain level. For others it was designed to grow incrementally over time. The old tax regime was modelled on the successful chengbao system in China’s rural areas – where the state would contract-out farmland to individuals and collect a percentage of the profit generated. The chengbao system was able to coexist with the central government’s role in economic planning and coordinating local economic activities. However, as a revenue generator for the state, the chengbao-style tax regime was inherently problematic. As the economy took off post – 1978 under Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening up, the tax share captured by Beijing declined sharply, constraining the center’s ability to deliver basic public services, and weakening its control over the economy (Figure 1).

In the 1980s, Beijing made three revisions to the Chengbao-style tax split formula to rationalize the core aspect of the center-local fiscal dynamic, but failed to keep the ratio of China’s fiscal revenue to gross domestic product (GDP) from falling. That ratio declined from 28.2% to 12.3% from 1979 to 1993, and the ratio of central to total government revenue fell to 22% from 40.5% over the decade from 1984 to 1993. Worse, China underwent severe inflation in the late 1980s, caused by overheated local economies and the failure of two-track price reforms Beijing engineered. To arrest the decline of the “two ratios”, and more importantly, to strengthen Beijing’s power and straighten out the center-local relationship, Premier Zhu spearheaded an overhaul of the fiscal system starting 1993, reclassifying the types of taxes, dividing up central and local administrative powers, and redefining ways to share tax revenues. The new regime that replaced the old negotiation-based system is known as fenshuizhi, or the tax-assignment system. Coming on the heels of the economic and political debacles of 1989, Zhu’s 1993 and 1994 reforms, like Xi’s today, were possible, despite livid local opposition, only because of their existential necessity.

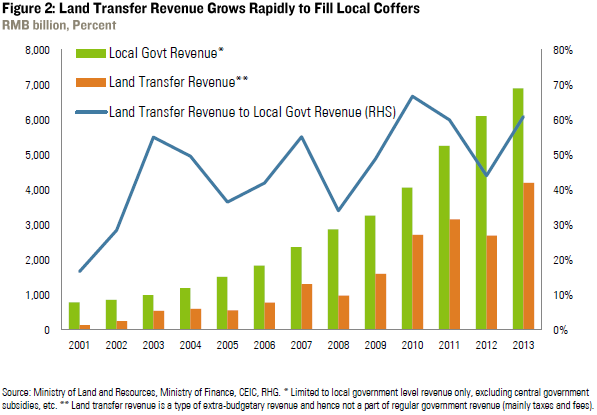

The new regime promptly replenished central coffers: in 1994, the central government’s revenue more than doubled from the previous year, and Beijing’s share of total fiscal revenue soared to 56% from 22%, while its share of expenditures increased only two percentage points. In the following decade, the center continued to tax more than it spent. As the imbalance in the center-local fiscal relationship grew, it forced local governments to find off-budget revenue sources to fund their needs (Figure 2).

Zhu’s reforms solved the problems of the 1990s, but sowed the seeds for today’s, including local government reliance on land financing, and the dangerous practice of using local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) which was buoyed by Beijing’s stimulus program in 2008. The LGFVs raise funds based on local government endorsements and assets, such as land and government-held equity. When Beijing cut fiscal and monetary stimulus in 2010, LGFVs were forced into the arms of shadow banks to meet their funding needs for long-term projects, as capital from legitimate channels was squeezed. The 1994 reforms also created or did not address problems such as redundant tax levies for service sectors, large numbers of murky “special transfer payment” programs, and a marketplace distorted by a patchwork of different local tax policies that increasingly threaten China’s economic vibrancy and sustainability.

Abuse of farmers in the course of local government land transactions is well known today and fundamental fiscal and tax reform is required to stop it. A variety of piecemeal reforms were debated in recent years to improve rights and social justice around land, but, in practice, local government and economic growth imperatives have trumped the rights of rural citizen almost every time. What has raised this reform issue to central attention is more debt burdens than farmer rights. Even with land sales, the National Audit Office has identified massive and unsustainable debt creation by local governments and LGFVs, along with dangerous entanglement with shadow banks. These systemic risks have pushed the Xi leadership to accept the need for a new round of fundamental reform.

New Reforms

The Xi team spelled out the objectives for fiscal and tax reforms in the Third Plenum decisions:

“Public finance is the foundation and a critical pillar for state governance. A scientifically designed fiscal and tax regime is the institution that guarantees resource allocation optimization, market unification, social equality, and long-lasting security and peace for a nation.”

On June 30th – the eve of the Communist Party’s 93rd anniversary – the Politburo approved a national plan for deepening fiscal and tax reforms, which specified reform priorities and tasks and, to the surprise of some, set a clear deadline of 2016 to basically finish the major tasks. This interim deadline is a feature Chinese reforms have been short on in recent years, other than in the nebulous Five Year Plans. This clear statement of reform tasks and a deadline demonstrate significant high-level commitment, and support the view that China’s reforms are moving ahead despite bureaucratic inertia, institutional resistance, and widespread skepticism. To put it in the negative, without evidence of a strong 2016 interim commitment on center-local fiscal and tax reforms, it would be hard to be sanguine about the 2020 outlook.

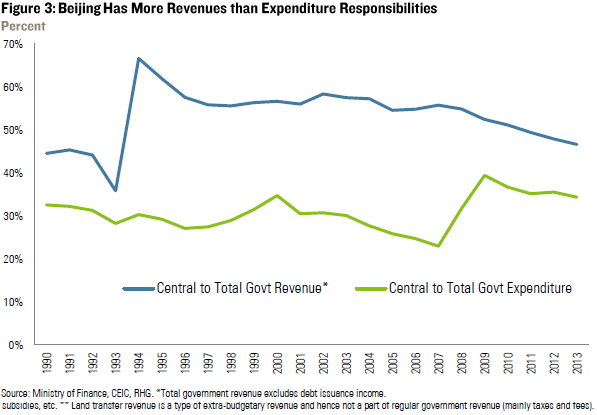

In a lengthy interview with state news agencies, Finance Minister Lou Jiwei explained the blueprint, though details are not yet public. Lou drew an outright comparison between the 1994 reforms and the new plan; he said the former straightened out the revenue relationship between the state and enterprises, and between central and local governments, while the current reforms are to redefine the roles and functions of central and local governments, enhance overall state governance, and improve bureaucratic efficiency (Figure 3). In other words, the current fiscal and tax reforms are as much about political reform as economics.

Minister Lou clarified that the three most urgent tasks for fiscal and tax reforms, in the order they should be carried out, are to: 1) improve budget management; 2) improve the taxation system; and 3) rationalize the center-local fiscal system to match governments’ administrative responsibilities with financial resources.

Improving budget management means transparent budgeting, better fiscal decisions, and better enforcement of fiscal discipline. Today, sub-central budgets are in the dark and standards vary, limiting the Ministry of Finance’s ability to supervise. The soft budget constraints for local governments and state-owned companies render them less sensitive to funding costs than competitive entities, crowding out borrowers essential to China’s growth. Minister Lou pledged to enhance the clarity of the process and clean up the messy “special transfer payment” program which has generated tremendous economic rents. Lou said budget supervisors’ focus would shift towards expenditure items and away from the scale of deficits, and would create a multi-year balance framework to better guide the year-to-year budgeting process. This move is designed to alter the incentives for local cadres when making fiscal decisions, so they begin to think beyond the short-term and invest efficiently. Lou also said the government plans to regulate and reduce the number of fiscal items for which expenditures are proportionally determined by total fiscal balance growth or GDP growth. Such mechanically budgeted items account for nearly half of total fiscal expenditures now and have ossified the fiscal resources that could otherwise be spent in more needed fields.

Enhancing the tax regime consists of pushing ahead the VAT-for-business-income-tax reform (with a previously stated completion date of 2015) to expand tax resources for local governments and scrapping different local tax policies that distort the marketplace. New property and resource taxes, along with diverting bigger share of the existing consumption tax to local governments, is expected to make up the local revenue gap. According to Minister Lou and previous plans, China will transform the resource tax from a unit tax to an ad valorem tax as soon as this year, while increasing the consumption tax rate for polluting business and luxury goods. On the legislative front, Lou said henceforth no regional policies can grant fiscal benefits to enterprises without the State Council’s approval, and no laws or regulations can stipulate tax policies that are more preferential than national taxation laws and regulations permit. The overall goal of tax reform is to reduce local government’s addiction to land financing and inefficient investment, and create a market-driven economy for businesses.

Rationalizing center-local fiscal dynamics is centered on clarification of the roles and administrative powers for central and local governments, and reassignment of financial resources to match responsibilities. Currently, Beijing claims almost half of national fiscal revenue while it lays out only a third of expenditures. To address this imbalance Minister Lou said the spending responsibility for Beijing will be strengthened, including concentrating spending items concerning nationwide public services and market regulations in the hands of Beijing, and the items entrusted to local government will be reduced.

CONCLUSION

Observers of China’s economic policy reforms pay huge attention to minute-to-minute shifts in exchange rate values and foreign investment restrictions. But the real bellwether for China’s direction is internal tax and center-local fiscal reform. We stressed a year ago that this would be a litmus test for the sincerity of reform. Measures to date had been modest. With the Politburo’s decision to push ahead with bold fiscal and tax reforms, another brick in the wall of reform skepticism has been removed.

This has commercial implications. As we wrote about China’s industrial consolidation institutions in February 2013, the biggest impediment to major market restructuring in a dozen overcapacity industries is the addiction of local officials to unofficial rents and revenues for want of better arrangements with Beijing to cover expenditure obligations. With a 2016 interim deadline for center-local fiscal reform now on the table, a dramatic investment banking bonanza may be on the horizon.