Collision Course: The Future of Chinese Carmakers in Russia

Chinese carmakers have made inroads into the Russian market, but are facing growing headwinds from Russia itself and the risk of increased scrutiny from Western policymakers.

Since Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, Chinese carmakers have come to dominate the Russian auto market, filling the void left by Western rivals. Lately, however, Russia has begun pushing back against the influx of Chinese cars. In October, Moscow hiked recycling fees that penalize foreign-made vehicles, imposing what amounts to a tariff on Chinese imports. While Russia wants Chinese vehicles, it is now insisting that carmakers produce them in Russia. The pushback shows how even China’s close geopolitical ally is averse to becoming a dumping ground for Chinese excess capacity. For Chinese OEMs, particularly those with global ambitions, investing in Russia is fraught with risk. If they do so, it could invite more scrutiny from Western policymakers, including in Europe, where the incoming European Commission appears determined to make China pay an economic cost for its support of Russia.

In this note, we examine the gains that Chinese carmakers have made in Russia, the dilemmas they now face in the market, and how the EU could respond to Chinese firms profiting from the Western exodus.

Hyundai out, Chery in: Chinese carmakers advance in Russia

On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, sparking a devastating war that has caused immense human suffering. In nearly three years of conflict, over one million people across both sides are estimated to have been killed or wounded. The economic fallout has also been severe: Ukraine’s GDP plunged nearly 30% in 2022 and isn’t expected to recover to prewar levels until 2030. In the West, Russia has become a sanctioned pariah state.

But there have also been winners. Chinese carmakers like Chery, Great Wall Motor (GWM), and Geely have seized the opportunity created by the withdrawal of Western automakers from the Russian market, moving in swiftly and establishing a dominant position.

Before the war, Russia ranked among the world’s top ten car markets, with 1.5 million passenger vehicles sold in 2021, just behind France and the UK at 1.6 million each. In that year, roughly 70% of vehicles produced in Russia came from Western brands, a figure that rose to 92% if joint ventures between Western and Russian companies are included. In Moscow, affluent consumers bought luxury Mercedes S-class models, while in Russia’s eastern provinces, Korean and Japanese brands like Toyota were the go-to choice. French carmaker Renault, in partnership with Avtovaz (producer of the Lada), relied on Russia for 18% of its global sales in 2021.

Following Russia’s invasion, however, international carmakers exited the Russian market in the face of rising political and public pressure, and sanctions that affected dual-use components like semiconductors. Most departing OEMs sold their assets to local entities for symbolic prices, effectively abandoning a once-lucrative foothold. Others liquidated their Russia operations entirely.

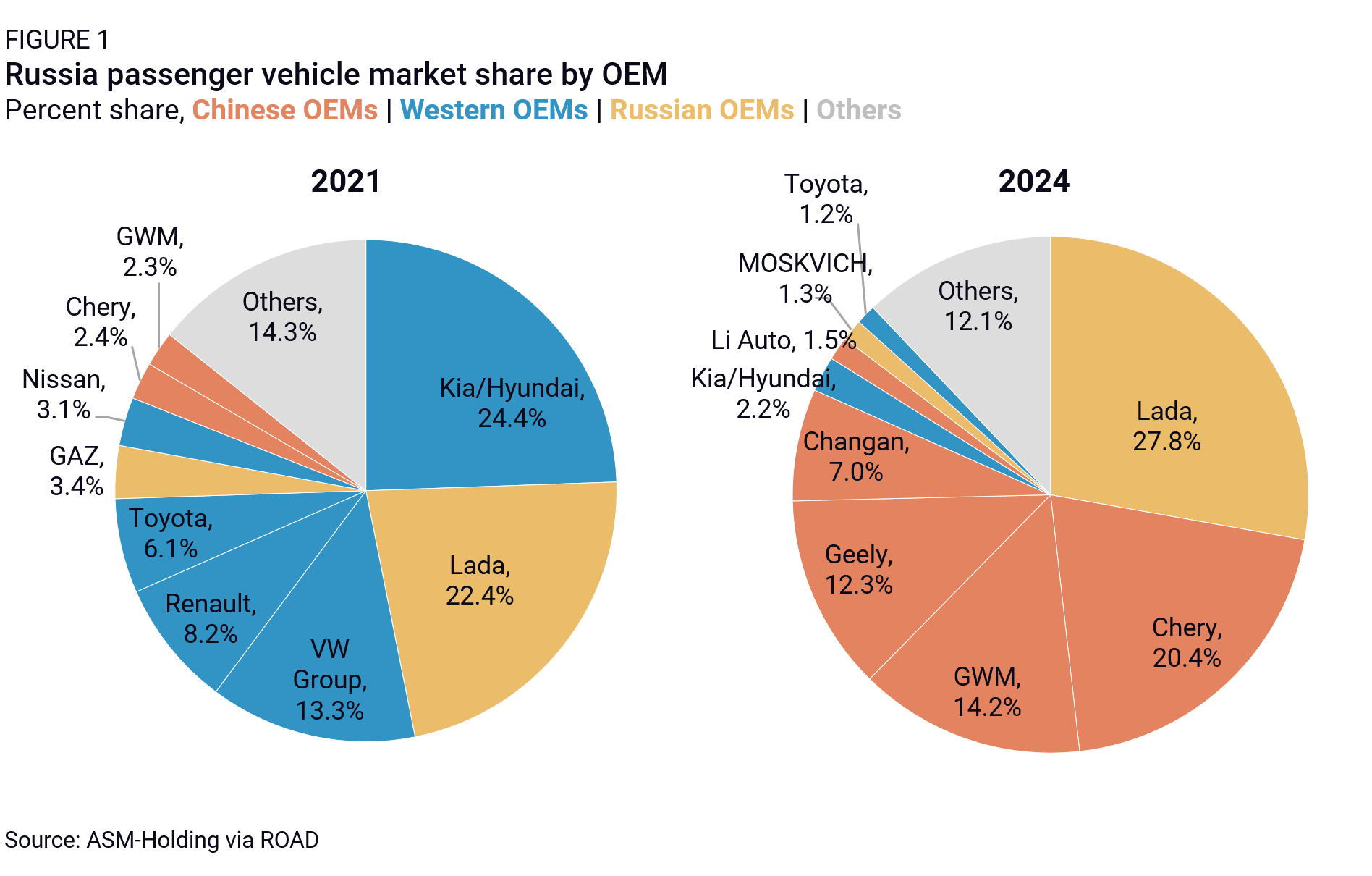

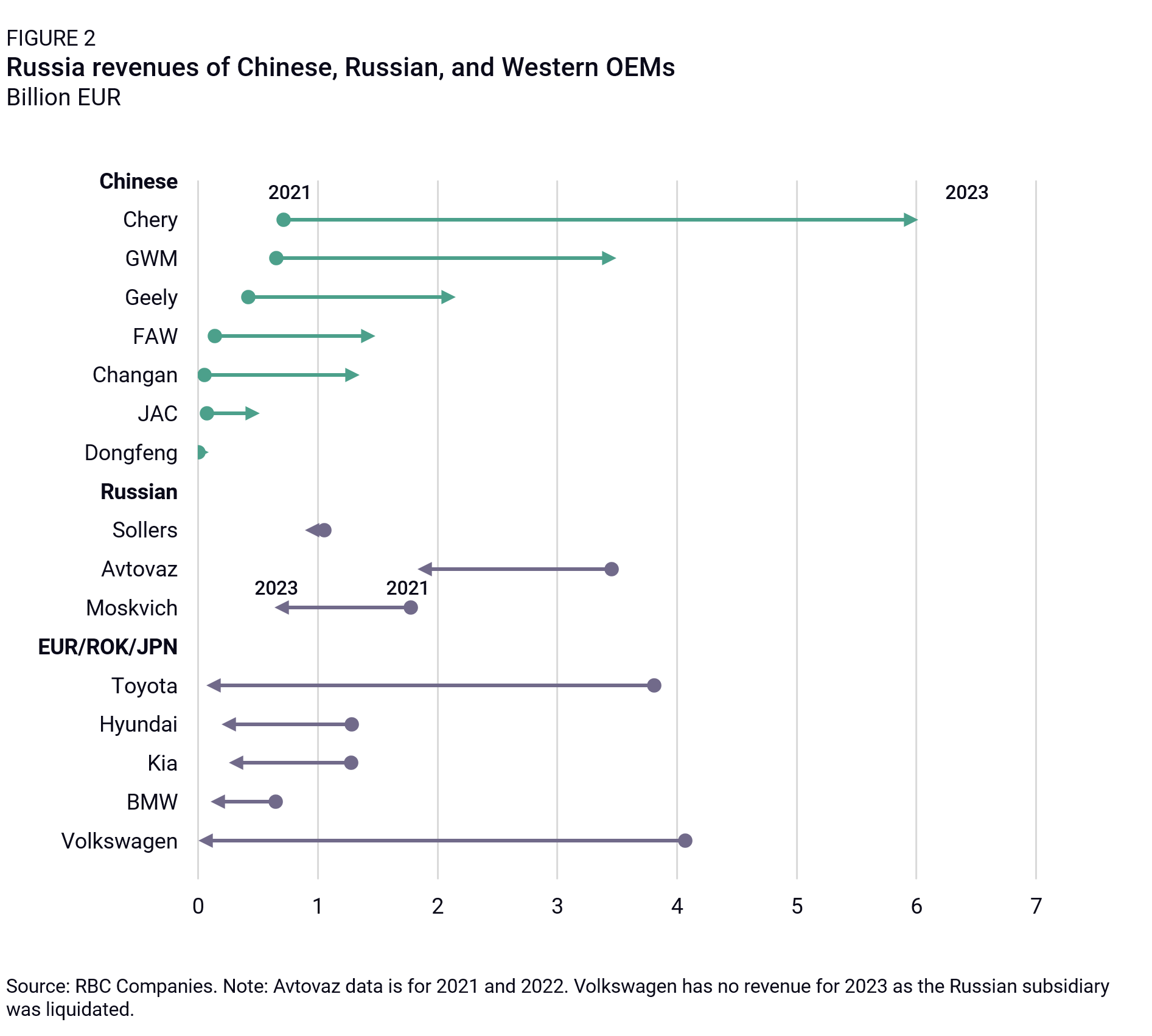

After they left, Russian producers like Avtovaz resorted to producing stripped-down, Soviet-era style vehicles which lacked modern components like airbags, anti-lock brakes, and automatic transmissions. But buoyed by the “no-limits” partnership sealed between Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping days before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Chinese automakers wasted no time stepping into the void. Their market share skyrocketed from 9% in 2021 to 61% in 2023. According to Russia’s leading carmaker, Lada, the dominance of Chinese brands is even starker in revenue terms, with 90% of sales now flowing to Chinese producers.

In short, Russia’s car market has undergone a dramatic transformation in the past few years, with Chinese carmakers emerging as the clear winners. Chery’s revenues in Russia have soared nearly 800% from 2021 to 2023, while OEMs from other countries outside Russia have seen their revenues plummet by over 90%. The Russian plant of GWM, the only one in the country that is owned by a Chinese automaker, had a capacity utilization rate of 123% in 2023, as extra shifts were added to maximize output. The plant is now slated for expansion. By 2023, over 50% of ex-China sales for both Chery and GWM came from the Russian market. Chinese carmakers’ high revenues are also bolstered by their role as key suppliers to Russian producers. State-owned JAC, for instance, provides engines and transmissions to Russian carmaker Sollers, deepening China’s integration into the Russian auto market.

Russia has also emerged as China’s most significant automotive export market. Between January and October 2023, China shipped 735,000 vehicles to Russia, accounting for 19% of its total passenger vehicle exports. Most of these are traditional combustion engine vehicles. Electric vehicles (EVs) comprised only a small fraction, reflecting low levels of EV demand in Russia.

From friends to frenemies: Russia sets new terms for Chinese carmakers

Russia’s leadership initially welcomed the influx of Chinese cars, which benefited Russian consumers and freed up domestic industry to focus on producing military goods for the war in Ukraine. But more recently, Moscow has sent signals that it does not intend to serve as a dumping ground for China’s overcapacity in ICE vehicles. These vehicles, increasingly out of favor in China’s domestic market, now face growing trade barriers in Russia.

In 2022 and 2023, Russia’s state-owned auto research institute NAMI and local car dealerships began acquiring abandoned foreign OEM assembly plants, often for symbolic sums like one ruble or euro (Table 1). To capitalize on reduced tariffs and shipping costs, several Chinese brands started using these and other Russian auto plants, assembling semi-knocked-down (SKD) kits rather than exporting fully built vehicles. These kits require minimal parts and labor for assembly.

Despite the availability of manufacturing facilities, Chinese carmakers have been hesitant to localize their supply chains in Russia. While GWM operates a plant it established in 2019 and Geely produces vehicles in Belarus through a JV with the Belarusian government, most Chinese automakers have opted for exports or asset-light SKD assembly. This reluctance is based on several factors.

First, they face pressure from Beijing to keep technology and value-added activities at home, pushing them to utilize the spare capacity of Chinese ICE production plants. Second, investments in Russia could open them up to accusations of supporting the country’s war economy, leading to possible sanctions. For some, this is not a risk worth taking, given Russia’s economic isolation and questions about the long-term potential of the market. While Russia-related sanctions imposed by Western countries on Chinese firms have focused on dual-use technologies, sanctions on Russian companies have been broader. Russian automakers, for example, have been sanctioned, affecting their collaboration with Chinese carmakers. For instance, Chinese state-owned automaker FAW—the JV partner of both Toyota and VW in China—halted a planned collaboration with Avtovaz after the latter was targeted by US sanctions in September 2023. A third impediment is Russia’s opaque bureaucracy and entrenched political interests, which can make starting and running local operations challenging.

Russia’s political elite harbored ambitions to create a robust domestic car industry long before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Amid a record surge in Chinese car exports in Q2 2024, they are now calling for protectionist measures.

In May 2024, President Vladimir Putin called for better cooperation with China in the production of cars—a signal that Moscow was keen for Chinese carmakers to invest rather than continuing to export. Avtovaz CEO Maxim Sokolov, meanwhile, has warned that the influx of Chinese cars poses “a real threat to the sustainable existence of the domestic automotive and component industries.”

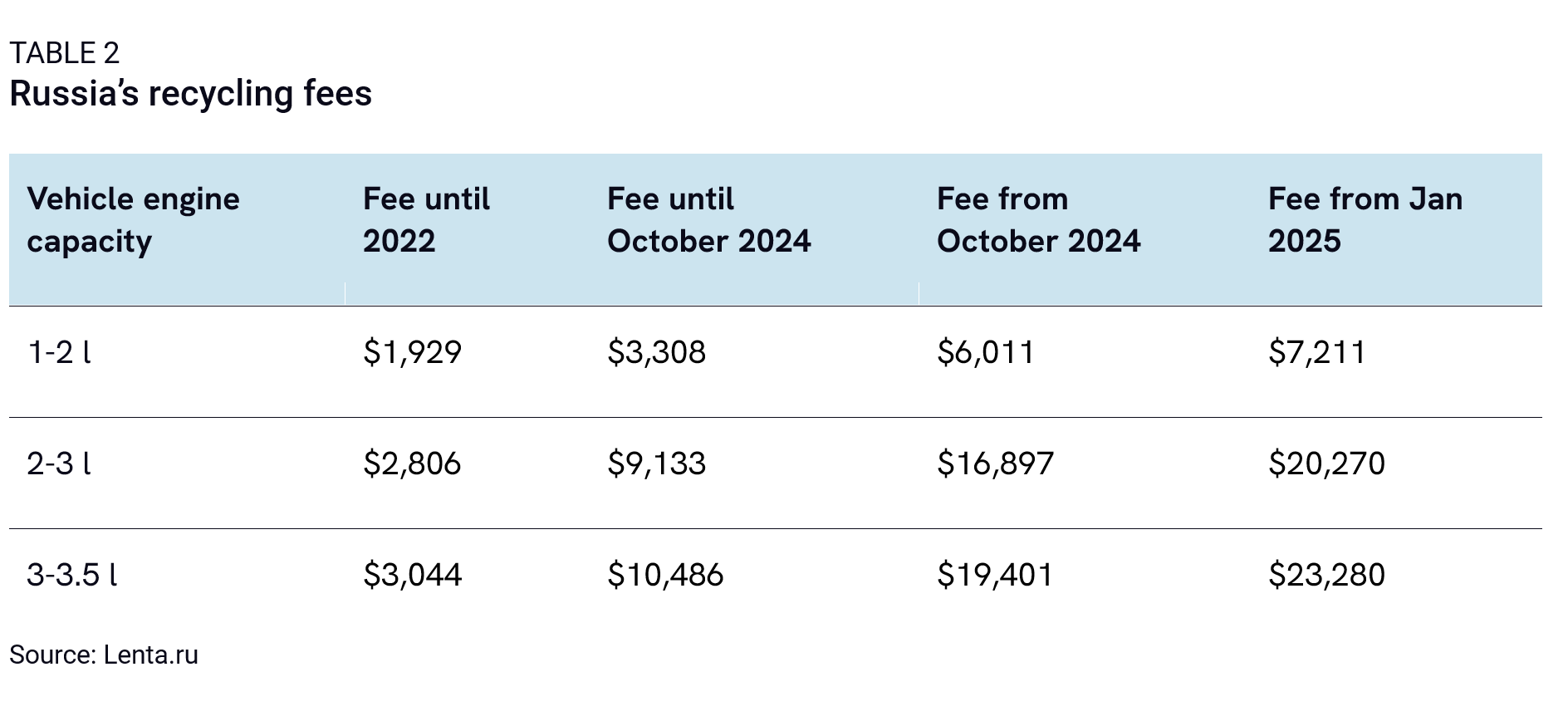

In response to these concerns, Russia’s Industry and Trade Ministry proposed a steep hike in recycling fees in July 2024 (which had already been increased in 2023). The recycling fee is a one-time charge for the future disposal of a vehicle, which the Russian government introduced in 2012 when it joined the WTO to prevent its market from being flooded by imports. The fees are reimbursed for domestic producers that meet localization thresholds, and thus act as a hidden tariff. The new hike, effective October 1, 2024, raised fees by 70-85% depending on engine size. They are to be increased by 10-20% annually through 2030.

For most OEMs Russia’s recycling fee is costlier than the EU’s countervailing duties on Chinese EVs

For Chinese exporters, the fees are prohibitive. From January 2025, Chinese carmakers will face more than $7,000 in additional costs for a 1-2L engine vehicle on top of the 15% import tariff, with larger vehicles incurring nearly $20,000 in fees. Chery’s Tiggo 7 Pro, one of the most sought-after Chinese vehicles in Russia, sells for $27,780. From January 2025, the recycling fee will equal more than a quarter of the price tag. This means that for most OEMs, Russia’s recycling fees are costlier than the EU’s countervailing duties on Chinese EVs. SKD assembly offers no relief under updated rules which prevent the reimbursement of recycling fees for such low value work.

There are signs that Russian pressure on Chinese carmakers to localize may be bearing fruit. In November, Sergei Chemezov, the head of Rostec (a defense conglomerate that owns Avtovaz), said following a trip to China that a major Chinese car producer was considering setting up a plant in the Moscow region or Siberia. “They are ready to help us,” Chemezov was quoted as saying.

Implications

Russia’s recycling fee hike and mounting calls from its domestic industry for protectionist measures mark a turning point in China-Russia auto relations. The changes have forced Chinese carmakers to reassess their strategies and exposed flaws in China’s broader export-driven growth model. If they lead to greater Chinese investments in Russia, they could invite reactions from Europe, where policymakers are growing more concerned about China’s deepening economic relationship with Russia, including the export of technologies that are being used on the battlefield in Ukraine. Adding complexity to the outlook is the potential for US policy changes under the incoming Trump administration.

What will Chinese carmakers do?

China’s export-centric approach to the Russian market appears to be reaching its limits. In October—the first month after the fee increase—exports remained strong but fell from their September peak. Another fee hike scheduled for January will further squeeze profitability, forcing Chinese automakers to reconsider their Russia strategies.

It is likely that Chinese OEMs will initially try to pass on price increases to consumers. But that strategy is problematic for several reasons. First, Russian interest rates surged from 16% in June to 21% at the end of October, depressing demand and making buyers more price conscious. Second locally produced Ladas and GWM vehicles, whose prices are not inflated by recycling fees, are available. Moreover, a failure to commit to localizing production and supply chains in Russia over the next year could lead to even tighter restrictions. Moscow’s message is clear: We welcome Chinese cars, but please build them in Russia. The responses of Chinese OEMs is likely to vary.

- GWM: GWM is doubling down on Russia, expanding capacity from 150,000 to 200,000 units and localizing production with a new engine plant. Globally, the company is pivoting away from Europe toward China-friendly markets like Brazil and Thailand, moves that help insulate it from the impact of sanctions. However, its exports of the iconic Mini EVs, produced in partnership with JV partner BMW for advanced economies, would be at risk if the company were to face sanctions.

- Chery: Chery has yet to commit to significant investments in Russia. However, the company has started assembling SKD kits in factories previously owned by Western automakers, including in cooperation with Russian carmakers under US sanctions. This willingness to take risks, coupled with Chery’s commercial success in the Russian market, suggests the company may increase localization efforts if it becomes necessary to maintain its position as the leading Chinese carmaker in the market.

- Geely: Deeply embedded in global markets through its ownership of Volvo, Geely may want to avoid making direct investments in Russia that could attract scrutiny or even sanctions. It will likely continue to rely on exports, SKD assembly, and its Belarus JV to serve Russia as long as these remain profitable.

- SOEs (FAW, Dongfeng, JAC): These state-owned carmakers may expand SKD assembly in Russia but are constrained by MOFCOM’s risk assessments and Beijing’s desire to keep value-added activities at home. Greater engagement in Russia could expose them to sanctions and jeopardize their global partnerships with Western OEMs in China.

- EV players (BYD and startups): Largely absent from Russia’s weak EV market, they are unlikely to increase engagement for now.

Cracks in China’s export model

Mounting pressure on Chinese carmakers to invest in Russia shows the cracks in the country’s export-driven growth model. Even its closest geopolitical partner seems fed up with the reluctance of Chinese OEMs to invest in local production facilities. Russia, of course, is not alone. In a sign of the growing headwinds for China’s auto exports worldwide, Brazil has raised tariffs on imported vehicles, Europe has imposed countervailing duties on Chinese EVs, the US plans to ban Chinese-owned carmakers’ vehicles from its road on security grounds and Chinese-owned plants in Thailand are competing with China-based plants that produce cars for export. These developments suggest that China’s passenger vehicle exports, which reached a record high in August 2024, may have already peaked.

The combination of Russia’s new fees and restrictive measures in other markets is likely to accelerate domestic consolidation and plant closures within China’s auto industry as only the biggest and most successful players will be able to set up overseas plants. Policymakers in Beijing are aware of these challenges. Recent moves, such as an extension of auto trade-in policies to stimulate domestic demand, reflect their concern. Yet, these efforts address the symptoms rather than the structural factors at play.

European reaction: Costs of success in Russia

The success of Chinese carmakers in Russia, and the potential for deeper engagement, risks attracting EU scrutiny and could ultimately prove costly for their European expansion plans. The incoming European Commission is determined to make China pay an economic price for its support of Russia. The EU’s top diplomat, former Estonian prime minister Kaja Kallas, made this clear during her parliamentary hearings.

The EU’s countervailing duties against Chinese EVs, effective from late October 2024, reflect a broader strategy to shield Europe’s auto sector from what policymakers in Brussels view as unfair competition. The success of Chinese automakers in Russia, particularly if it is underpinned by investments, could spur further action. European policymakers are unlikely to sit on their hands while Chinese carmakers that have profited from the exodus of European rivals in Russia, set their sights on the EU market. Looking ahead, one can imagine calls to impose costs on Chinese OEMs that swooped into Russia to fill the gap left by European carmakers.

A similar dynamic is playing out in the aviation industry, where Chinese carriers continue to fly over Russian airspace, reducing their costs and flight times compared to European airlines that are flying around Russia due to the war. Lufthansa and IAG, the parent company of British Airways, Iberia, and other carriers, have urged the EU to address this competitive distortion. Such calls could spill into the automotive sector. France’s Renault, for example, has lost significant business in Russia and will not be as concerned as German OEMs about retaliation from Beijing, given its comparatively small presence in China.

The “NO LIMITS” Act, proposed by the US Select Committee in April 2024, offers EU policymakers a blueprint for possible action. The act proposes to expand dual-use sanctions on Russia to include automobiles, directly naming Chinese carmakers like Chery, GWM, and Changan. It would also set a 180-day deadline for them to end exports to and local production in Russia. The bill stalled in Congress and is unlikely to advance in its current form, but it points to a growing backlash against Chinese carmakers that have profited from Russia’s war.

If China does not heed European warnings about its support for Russia, EU policymakers could decide that action against Chinese firms that have expanded their presence in Russia at the expense of European firms is necessary. Targeting Chinese carmakers for exporting vehicles to Russia seems far-fetched. But penalizing companies that are localizing and, for example, helping to onshore production of dual-use components like electronic control units and semiconductors (which are heavily incentivized under Russia’s localization policies) could eventually be considered. For now, the likelihood of EU sanctions against Chinese carmakers remains slim. EU sanctions require unanimous approval, and member states such as Hungary or Germany would likely resist because of ties to the Chinese auto industry and fears of retaliation.

The Commission could also explore applying its trade defense and level playing field tools in innovative ways. The Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR), for example, can be applied ex-officio, without the request of member states. Policymakers could try to argue that Chinese profits earned in the Russian market which are then reinvested in Europe distort competition in the EU, because the same opportunity does not exist for European firms. Chery, now the leading Chinese carmaker in Russia and reportedly using former Western assembly plants, could be especially exposed. Still, taking action under the FSR would be contentious. Targeting companies like Chery is likely to invite pushback from Spain, which views Chery’s joint venture with EV Motors as a flagship project for Spain’s reindustrialization and a boon for local industry.

The arrival of Donald Trump in the White House on January 20 could change the dynamic we have laid out in this note. Trump vowed during the US election campaign to bring the war in Ukraine to an end. It is unclear how he will do so, but were the war to be frozen, it could have an impact on Russia’s auto industry and the Chinese firms supplying it. For example, if a truce involves lifting US sanctions, it could lower barriers for Chinese carmakers operating in Russia, while potentially encouraging some Western manufacturers to consider reentering the market. What does seem certain is that the honeymoon period for Chinese carmakers in Russia, during which they benefited from uncontested access to the market with few strings attached, may be drawing to a close.