Divergent Paths: Chinese FDI in Europe and North America in 1H 2018

While Chinese outbound FDI in Europe has rebounded to around 2016 levels, investment in North America is now at the lowest level seen in a decade.

Chinese outbound foreign direct investment (OFDI) dropped sharply in 2017 for the first time in more than a decade due to stricter Chinese controls on outbound flows as well as increasing foreign regulatory pushback against Chinese takeovers. Chinese outbound investment has since stabilized, but with the balance in advanced economy flows shifting from North America to Europe. In the first six months of 2018 this shift accelerated.

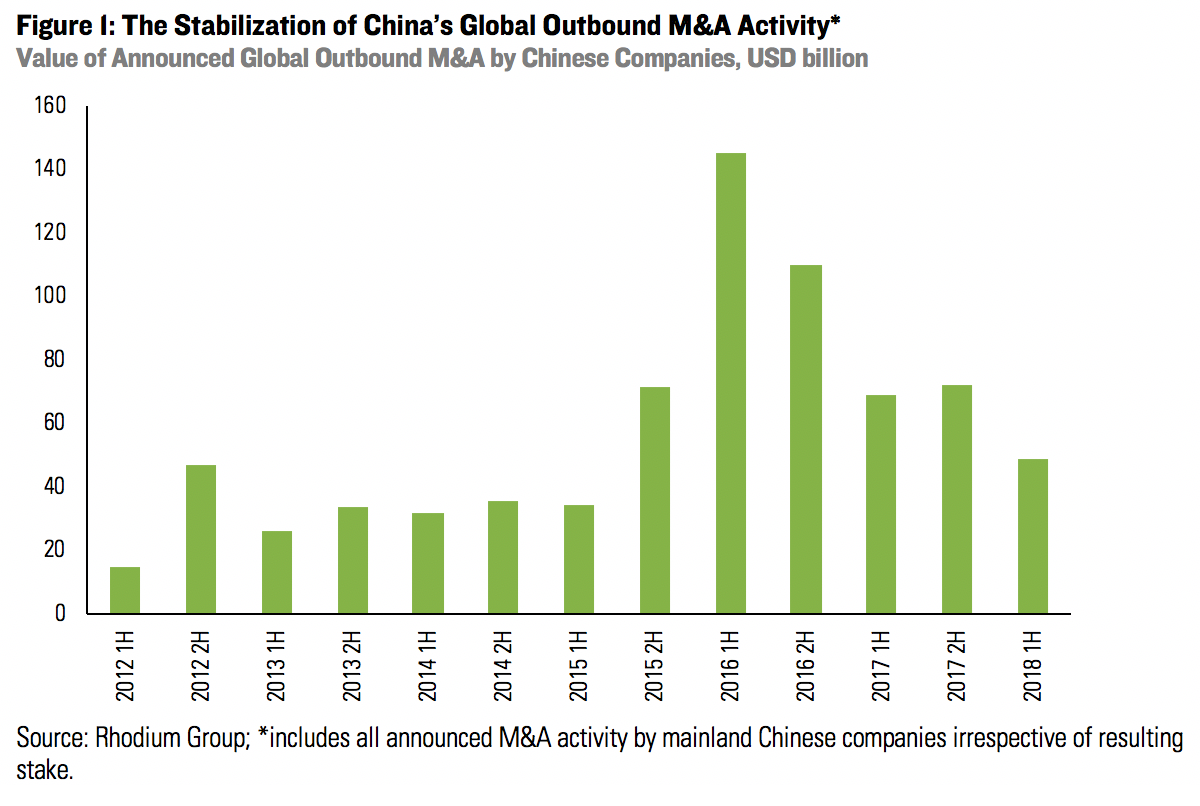

Chinese Outbound Investment Stabilized After a Sharp Drop in 1H 2017

After a banner year in 2016, Chinese outbound investment fell sharply in the first half of 2017. Since then outbound flows have stabilized. The bi-annual value of newly announced global M&A activity by mainland Chinese companies dropped from a peak of $145 billion in 1H 2016 to an average of $70 billion in 1H and 2H 2017. In 1H 2018, the value of newly announced outbound M&A by Chinese companies globally reached $50 billion – a 32% drop compared to 2H 2017 but still significantly above the 6-month period average of $39 billion seen in 2013-2015 (Figure 1). Official Chinese statistics for the first half of 2018 are not available yet but preliminary data points from the Ministry of Commerce suggest a rebound of non-financial outbound direct investment in the first five months of 2018 compared to the same period in 2017.

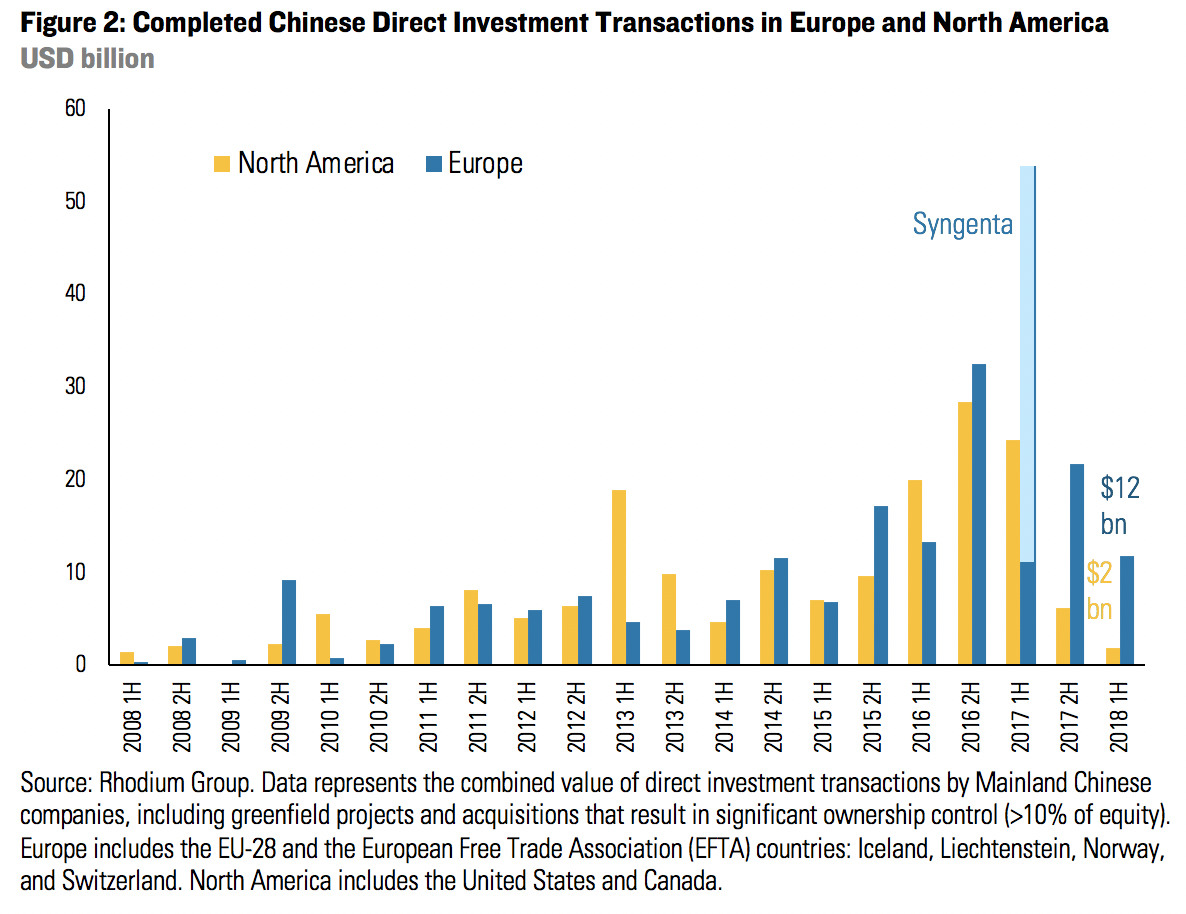

Chinese FDI Has Held Up in Europe While Dropping Sharply in North America

The stabilization of Chinese global outbound direct investment masks divergent geographic trends. While Chinese OFDI in Europe has rebounded to around 2016 levels, investment in North America is now at the lowest level seen in a decade: 1H 2018 saw $12 billion of completed Chinese FDI transactions in Europe and $2 billion in North America (Figure 2).

North America’s paltry 1H 2018 investment total continued a downtrend that started more than a year ago. Chinese OFDI in the region peaked at $28 billion in 2H 2016 before falling to $24 billion in 1H 2017, $6 billion in 2H 2017 and a seven-year low of only $2 billion in 1H 2018 (a 92% year-over-year decline). Deal activity is depressed in both the United States and Canada. Chinese companies have also divested assets at an unprecedented pace in North America so far in 2018, with several prominent investors during the 2015-2016 boom forced to sell holdings as part of a financial clean-up and tightening campaign back home in China. In total, we count $9.6 billion of completed divestitures in North America by Chinese firms in the first half of 2018. Another $5 billion of asset divestitures are pending.

Europe has also seen a drop in Chinese investment over the last year, but this decline came from a higher base and has been much less pronounced: Completed Chinese OFDI peaked in 1H 2017 (thanks to ChemChina’s $43 billion Syngenta acquisition) before falling to $22 billion in 2H 2017 and $12 billion in 1H 2018. Excluding Syngenta, Chinese investment in 1H 2018 actually increased 4% year-on-year. And if we count Geely’s investment in Daimler (slightly below the 10% threshold for FDI), the 1H 2018 total would have been around $21 billion, or around ten times the value in North America. Sweden ($3.6 bn) was the largest European destination for Chinese investment in 1H 2018 due to Geely’s investment in Volvo Group, followed by the UK ($1.6 bn), Germany ($1.5 bn), and France ($1.4 bn). Similar to North America, Chinese companies started to divest assets in Europe with nearly $1 billion of assets sold in 1H 2018 and another $7 billion pending.

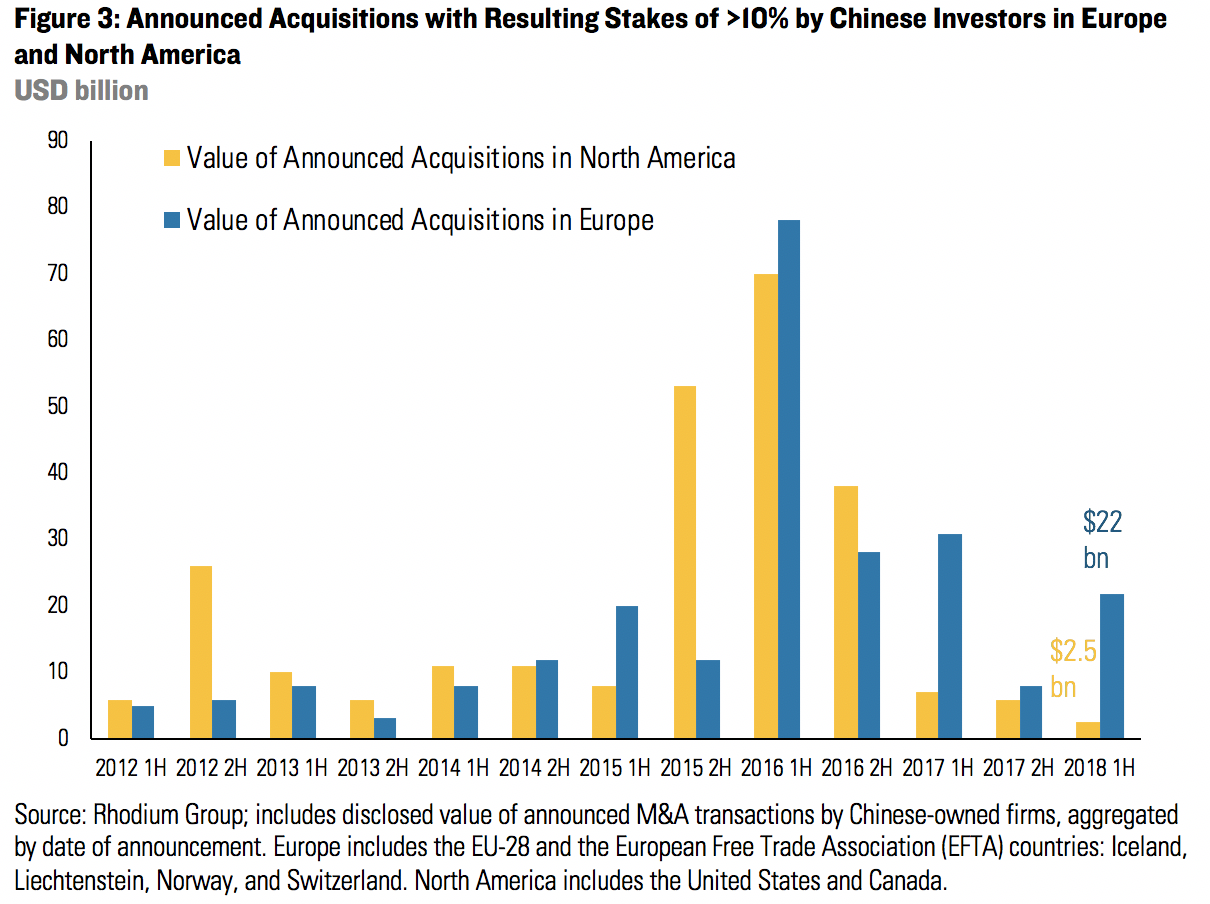

Discrepancies in Newly Announced Deal Activity Are Even Larger

In terms of newly announced transactions, the discrepancy between Chinese OFDI in Europe and North America is even more pronounced. Over the past six months, the value of newly announced Chinese M&A in Europe exceeded that in North America by a factor of nine.

North America saw less than $2.5 billion of newly announced M&A transactions in 1H 2018, with most deals targeting US companies. In comparison, 2017 saw more than $5 billion of newly announced M&A deals in each bi-annual period, while the three half-year periods from 2H 2015 to 2H saw more than $50 billion of newly announced deals on average per period (Figure 3). Only a handful of small and medium-sized North American deals are currently pending including Harbin Pharmaceutical’s investment in GNC ($300 mn) and Meisheng’s investment in JAKKS Pacific ($51 million).

In contrast, Europe saw more than $20 billion of newly announced Chinese M&A deals in 1H 2018. The biggest announced transactions were China Three Gorges’ $10.8 billion bid for EDP (initial bid rejected) and Geely’s investment in Volvo Group (estimated over $3 billion, completed). If we were to include stakes of 10% and less, this would add over $9 billion to the newly announced total in 1H 2018, mostly due to Geely’s investment in Daimler which was completed in Feb 2018.

Chinese and Overseas Regulatory Policies are Responsible for Divergent Patterns

The initial decline in Chinese OFDI was primarily caused by Chinese regulatory tightening over outward investments. Facing large capital outflows, Beijing began to crack down on outbound FDI in the second half of 2016 and instituted a new OFDI management system geared toward limiting the scale of outflows and restricting investments in specific sectors (real estate, hospitality, entertainment, and those with a financial nature). These restrictions continue to impact Chinese outbound investment in both Europe and North America, manifesting in lower aggregate outflows, a smaller average deal size ($48 million in the US, $161 million in Europe in 1H 2018) and a precipitous drop in investment activity among highly-leveraged large private conglomerates like HNA. These firms are now heavily constrained by direct government intervention as well as tighter financial conditions at home.

Overseas regulators have also played a critical role in curbing Chinese investment in both regions through the tightening of foreign investment security screening regimes. In response to perceived threats from China and other foreign investors, many OECD economies are now in the process of reviewing and updating these regimes.

In the United States, 1H 2018 saw the Trump administration continue a trend of increased scrutiny of Chinese takeovers through the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). In addition, slightly different versions of the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA), which aims to modernize the scope and process of CFIUS security screenings, were passed in the Senate and the House. The legislation would expand scrutiny to investment modes including venture capital and greenfield investment and would task the Department of Commerce with more strictly controlling outbound transfers of technology. The bill is now at an advanced stage of reconciliation between the Senate and House. The Trump administration also strongly considered additional restrictions for Chinese investors in late 1H 2018 as part of the Section 301 investigation into Chinese intellectual property practices but backed off at the last minute. Coupled with the broader deterioration of US-China economic relations, US regulatory investment hurdles have aggravated uncertainty for Chinese investors and led to the collapse of Chinese investment activity in 1H 2018.

Canada has not made any major changes to existing laws or investment screening practices. However, the Trudeau government rejected China Communications Construction Group’s high-profile takeover of construction firm AECOM in March 2018 citing national security concerns, showing that Chinese investors face similar uncertainties in Canada.

In Europe, Brussels initiated a process to draft a pan-European framework for coordinating the screening of inbound foreign acquisitions in September 2017. There has also been significant action at the member state level. For example, after a widening of FDI controls last year to include more industrial sectors, German leaders recently proposed a re-examination of the German foreign investment screening mechanism after Geely took a stealth stake in Daimler. In the UK, the government expanded its powers to review M&A transactions that may raise national security concerns while the UK Parliament recently adopted proposals to lower the threshold for the review of foreign acquisitions in a series of technological sectors. And on June 18, the French government unveiled draft legislation providing for increased control over inward investments in strategic and high tech sectors spanning from artificial intelligence to nanotechnologies.

Despite these developments, the number of formally blocked Chinese transactions in Europe remains very modest and most reviewed transactions continue to be approved (including Creat Group’s acquisition of Biotest, Legend’s acquisition of Banque Internationale a Luxembourg (BIL), and Geely’s investment in Saxo Bank).

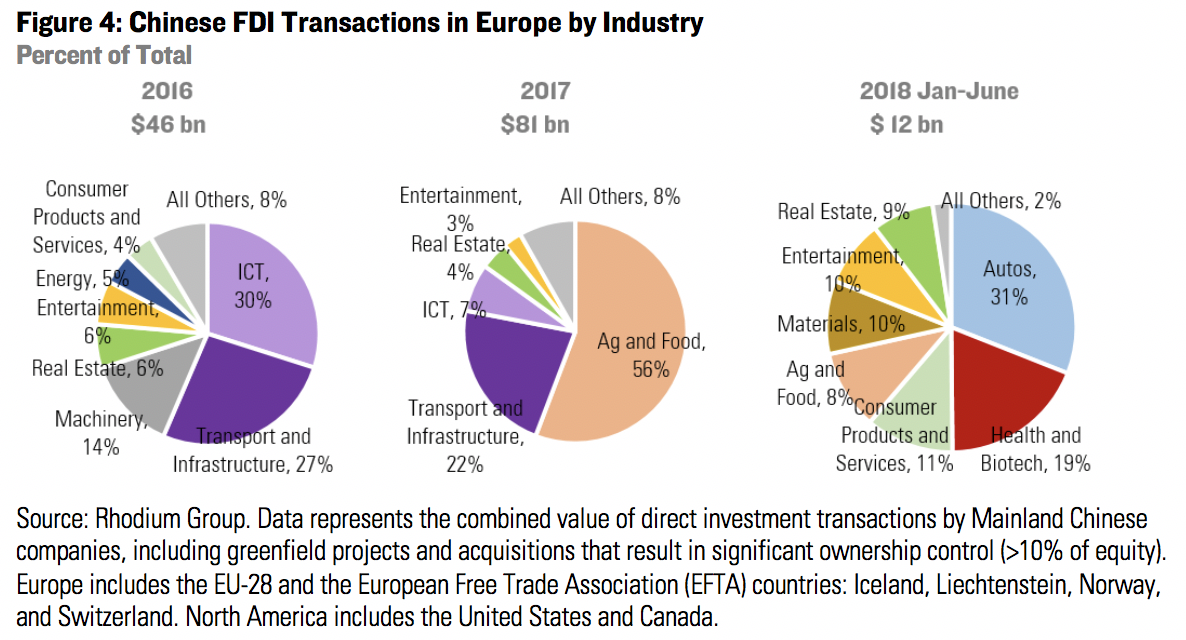

New Policy Realities Shift the Target Industry Mix for Chinese Investors

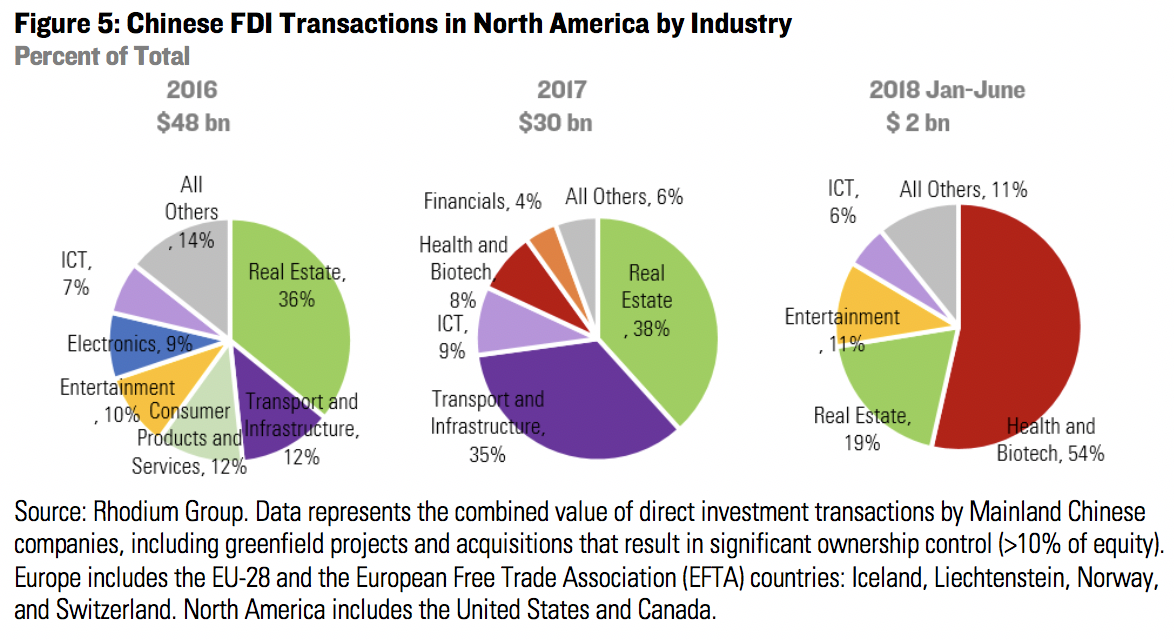

The industry composition of Chinese investment has also shifted remarkably in 1H 2018 in both Europe and North America. “Real economy” sectors such as automotive, health and biotech, and consumer products and services became top recipients for Chinese FDI. The real estate and hospitality sector lost its top spot but still remained a sizeable attractor for Chinese capital in both regions.

In Europe, agriculture and food, transport and infrastructure, information and communications technology (ICT), and real estate and hospitality were the top four sectors in 2017. In 1H 2018, autos, health and biotech, and consumer products and services became the top sectors (Figure 4). The industry mix for Chinese investment in Europe is generally much more diverse than in North America.

In North America, the biggest sectors for Chinese investment in 2017 were real estate and hospitality along with transport and infrastructure. In 1H 2018 the biggest sector was health and biotech (Figure 5). Real estate and entertainment continued to be main recipients of Chinese capital (despite Chinese policies to curb flows in these sectors), but nominal values declined significantly.

Outlook

With more than $20 billion of pending M&A transactions in Europe and only $2.5 billion in North America, the divergent paths seen in the first half of 2018 are largely locked in for the year. However, the outlook in both regions is complicated as policy pressures will persist and likely increase going forward.

In the United States, Congress is in the final stages of passing FIRRMA. While not specifically targeting China, the legislation will reinforce a stricter application of national security screenings of Chinese FDI as well as non-FDI transactions (such as venture capital). Provisions on stricter screening of outbound technology transfer developed in the United States could also impact Chinese greenfield FDI in research and development facilities in the US. Finally, growing trade frictions and uncertainty related to broader US-China economic relations will continue to unnerve potential Chinese investors.

Driven by concerns about Chinese acquisitions, Europe is also expanding its toolkit to review foreign inbound investments. The European Parliament has approved a proposal to expand scrutiny over foreign investments, and the European Council and the European Parliament have adopted their respective negotiation positions for their upcoming trilateral negotiations with the European Commission on an EU-wide investment screening mechanism. These tripartite consultations will start in July, and parties hope that an agreement can be reached by December. The new mechanism will increase and systematize information sharing between EU member states on investments with potential national security impacts. According to current draft proposals, sensitive sectors will include media, election infrastructure, data analysis, biomedicine and automobiles. Individual EU governments including Germany, Italy, the UK and France have also revised and tightened their investment screening frameworks or are in the process of doing so.

Finally, after a period of calm, China is facing a complex macroeconomic environment that may draw Beijing into a more interventionist stand on capital outflows. China’s currency depreciated significantly against the US dollar and other currencies in June, and officials are holding down interest rates to stimulate a slowing economy while relaxing liquidity controls moderately. With tighter monetary policy and higher rates in the US and elsewhere, conditions are ripe for encouraging greater capital outflows and hence pressure on China’s balance of payments. Stiffer capital controls could well follow, making Chinese OFDI even more difficult despite the inextricable logic of corporate desire for a bigger footprint abroad.