Don’t Misread Old Tealeaves: Chinese Investment and CFIUS

A series of derailed Chinese technology acquisitions in the US has triggered media reports about greater US scrutiny of Chinese investments. The release of an annual report by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS), which reviews foreign acquisitions for national security threats, further fueled this debate, showing China in the top spot for covered transactions for the third year in a row. This is serious misreading of the situation. The greater prominence of Chinese transactions in the work of CFIUS process does not reflect a tougher stance by the US against Chinese investment, but rather the sharp uptick in Chinese deal-making activity in the US, and a shift of that interest towards technology.

CFIUS in the Spotlight

A series of abandoned deals has put a renewed focus on the role of US national security reviews for acquisition overtures by Chinese buyers: In January, a Chinese consortium walked away from its $2.8 billion bid for Philipps’ Lumileds unit, citing US national security concerns; in February, Fairchild Semiconductors rejected a bid by a Chinese buyer as it saw too great risks that the deal would be rejected by CFIUS; this week, Unisplendor withdrew its bid to acquire a 15% stake in Western Digital after CFIUS announced to investigate the deal.

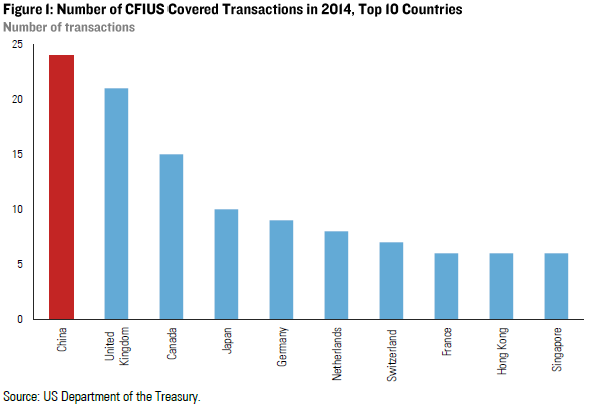

Last Friday, the release of the public version of CFIUS’ latest annual report to Congress further fueled those concerns. For the third year in a row, China was the country with the most “covered” transactions (Figure 1), which many interpreted as evidence that US was increasing the scrutiny on Chinese acquisitions.

More Deals = More Reviews

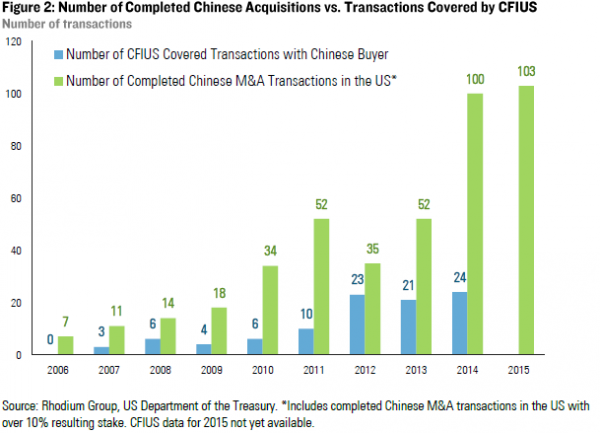

This popular interpretation of CFIUS numbers and deal dynamics is wrong. The rise of China’s prominence in CFIUS reviews is not proof of a more hostile US government stance toward Chinese investors. China’s rise to the top of the CFIUS ranking primarily results from the increase in the number of Chinese acquisitions. The number increased from an average of 13 in the period 2006-2009 to 43 from 2010-2013. In the following two years, the number of Chinese M&As doubled to 100 in 2014 and 103 in 2015 (Figure 2).

Compared to this exponential increase in the annual number of deals, the increase in CFIUS investigations is disproportionally small and the ratio of completed deals vs. CFIUS reviews has actually declined in recent years and would be even lower if one were to consider announced rather than completed transactions.

A Shift to technology

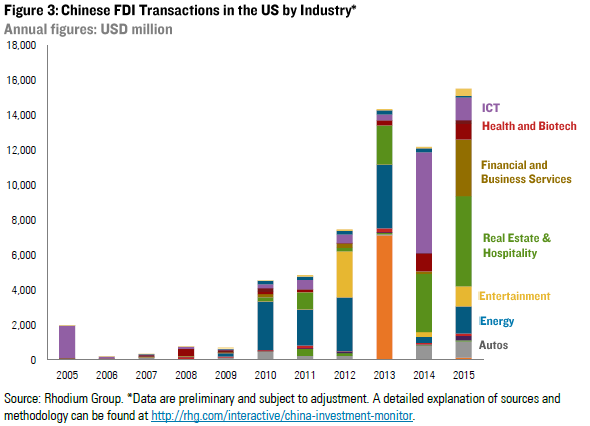

Another factor contributing to the growth in Chinese deals coming before CFIUS is the shift in size and industry target composition. Previously driven by a few large-scale deals in energy, the mix of Chinese FDI in the US has become more diverse since 2013 (Figure 3). Most importantly, a greater number of Chinese deals now target US technology assets, and the potential transfer of critical US technology is one of the key questions that CFIUS assesses.

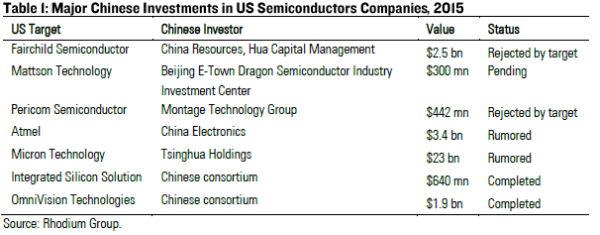

The increase in Chinese CFIUS attention over the last 12 months, for example, is partially the result of an unprecedented jump in Chinese overtures in the semiconductors space. Partially as a result of Chinese industrial policy, the US and other countries have seen a spike in formal and informal Chinese takeover offers. In the US alone, Chinese companies have successfully acquired two US semiconductor firms in the past 12 months (Figure 1), and they have formally or informally approached numerous other US companies with the intent to buy or forge strategic partnerships.

Anybody who is aware of historical patterns would have expected CFIUS to review those deals. In fact, CFIUS was born out of concerns about a foreign takeover of a US semiconductor company almost thirty years ago, Fujitsu’s bid for Fairchild Semiconductors in 1987 (yes, the same company that just rejected a Chinese bid out of CFIUS concerns). Over the past decade, CFIUS has reviewed and cleared many tech-sector transactions involving Chinese acquirers, beginning with Lenovo’s takeover of IBM’s personal computer unit in 2005. CFIUS interest in semiconductor acquisitions should not be misconstrued as a change in US policy or a discrimination against Chinese buyers.

Conclusions

CFIUS has been and remains an important regulatory hurdle that Chinese investors have to clear for acquisitions in the US. However, the recent increase in Chinese CFIUS exposure does not mean greater US scrutiny towards Chinese acquisitions, but it is largely the result of a rapid increase of Chinese deal-making in the US and a shift toward cutting-edge technology assets. The vast majority of Chinese overtures continue to pass CFIUS reviews without any problems, as the growing number of successfully completed deals across a wide spectrum of industries illustrates.