Eight Guardian Warriors: PRISM and Its Implications for US Businesses in China

As Beijing sets the stage for major reform measures and a new era of potential business opportunities in China, increasing tensions between the US and China on cyber security overshadow the upside. Edward Snowden’s revelations about the US Government’s PRISM program have not only changed US-China bilateral dynamics, but have also triggered a public campaign against US technology firms in China. The implications for business prospects of foreign firms operating in the world’s second largest economy are potentially far reaching.

PRISM adds another layer of potential barriers for US technology firms in China: Previously Chinese government objections to US tech firms operating in China were grounded in ideology; now the Chinese authorities and the public are increasingly worried about exposure to US technology and equipment because of espionage.

This is not just about Cisco but a broader group of US tech firms: Eight major US technology firms have been identified by state media as “guardian warriors” that have “seamlessly penetrated” China. Those firms may face difficulties in the Chinese market, while support for their domestic competitors could increase.

There are limits to Techno-Nationalism: While Chinese authorities may want to weed out foreign equipment in Chinese infrastructure, the cost of excluding foreign suppliers completely is prohibitive. The losses China would incur by reversing its hard-won market reforms far exceed any economic or political dividends from taking such a path.

For the past year, high-level talks between US and Chinese leaders have centered on the Chinese concept of a “new type of great power relations”. The phrase is derived from a concern that the rise of new powers has historically brought on severe security conflicts. By this logic, incumbent powers are increasingly combative as their soft and hard power declines; at the same time, ascendant states have more to gain from disrupting the existing global order. Washington and Beijing are wise to address this question – it is clear enough already how China’s rise could lead to confrontation.

President Xi Jinping has called economic and commercial relations the “ballast” in China’s external relations, underscoring the material benefits China’s emergence promises to an array of global powers. As Beijing prepares for a major new round of fundamental economic reforms starting this fall, the conversation should turn to enhancing new economic opportunities for China, as well as its global partners. But growing acrimony in US-China relations has overshadowed the upside. Swelling Chinese cyber-attacks on western businesses and recent revelations about US espionage practices and grievances over exposure to cyber espionage are widely shared between both countries.

The leak of PRISM hit Chinese media in early June, and played out in the headlines as two main storylines. One is the US’s “double standards”; while accusing China of hacking into US companies’ systems and conducting espionage, the US government is simultaneously monitoring other nations, companies and individuals. The second, far more threatening to US and other foreign businesses, is that official media are calling for a “de-Cisco campaign”.

At the end of June, the state-backed China Economic Weekly ran a cover story calling eight US companies – Cisco, IBM, Google, Qualcomm, Intel, Apple, Oracle and Microsoft – “guardian warriors” that had “seamlessly penetrated” Chinese society. The Weekly called Cisco “the most horrible”, given its significant – more than 50% – market share in China’s information infrastructure in financial, military, government and transportation sectors. The magazine also ran a long list of ‘the Eight’s’ projects within China, including Cisco’s upgrades of the People’s Bank of China’s Intranet, IBM’s facilitation in building the Yunnan province police bureau’s database, and Microsoft’s improvements to China Eastern Air’s information technology.

The article also pointed to a growing disparity in China and US law regarding the use of foreign equipment; despite the fact that earlier this year President Obama made it illegal for federal agencies to purchase Chinese IT equipment without a federal cyber-security investigation, no such law exists in China: “PRISM-Gate has made a significant impact on Chinese telecom operators. Everyone is under huge pressure. The next step for operators is likely to be a de-Cisco campaign from within,” the Weekly said. The term was quickly picked up by other official media, including Communist Party mouthpiece People’s Daily, China News Weekly, and a national TV network. A search for “de-Cisco campaign” (or Qu Sike Hua Yundong in Chinese) on the micro-blogging service Weibo produces hundreds of results, some of which read like this: “In an era of de-Cisco, analysts hold bullish views on local companies such as ZTE.”

This is not the first time that Cisco has faced a backlash in China. Last October the House Committee on Intelligence published a report asserting that leading Chinese telecom companies Huawei and ZTE pose national security risks to the US because their equipment could be used by the Chinese government to conduct espionage. Chinese state news agency Xinhua created a special section for the news, headlined “Huawei and ZTE are censored in the US, Cisco is allegedly behind the curtain” (that is, the driving force behind the allegations against Chinese companies made in the House report).

However, the most recent rhetoric calling for weeding Cisco out of China far exceeds the anti-Cisco outcry that followed the House report. On June 18, Cisco made an announcement on its Chinese website, saying “PRISM programs are not a Cisco project. Cisco’s network did not participate in those programs. In addition, Cisco does not monitor communications of private citizens or government organizations in China or anywhere in the world. We sell the same equipment globally, including to both China and the United States, with no customization for purposes of such programs.” But the Cisco pronouncement did not garner much attention, and the stock price of major domestic suppliers has risen strongly in recent weeks.

A Chinese State Information Center official was quoted by the Weekly as saying that the Chinese government did not pay sufficient attention to the safety of Internet infrastructure and information systems in the past, focusing instead on threats to the regime’s authority in the face of growing internet usage. As a result, comparative advantage in IT innovation has made US equipment suppliers’ products more popular than those of their Chinese counterparts. If rhetoric is any indication, Chinese officials have decided that it’s time to change that status quo. Uncomfortable with relying heavily on US technology in key sectors, the Chinese government has begun to spend massive sums developing its own supercomputers and satellite navigation systems. And now certain officials think some Chinese companies have grown mature enough to replace Cisco, Microsoft and IBM.

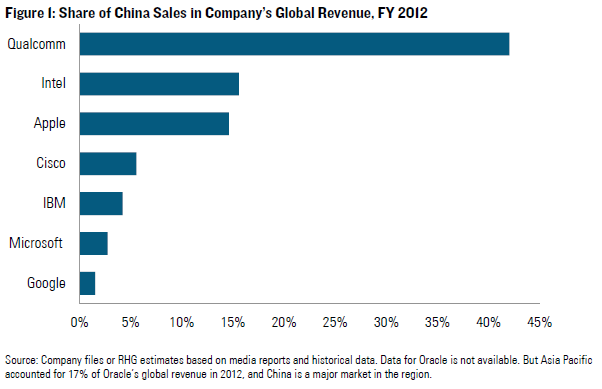

This does not bode well for US tech companies, for which China is often the most rapidly growing market and a large contributor to overall revenue and profits (Figure 1). In addition to price competition from homegrown competitors, US companies see their market share threatened by suspicions from China’s regulators, government and security leaders and corporate clients. Following the House report last year, leading telecom operator China Unicom replaced Cisco routers in one of its backbone networks, citing security concerns. It would be surprising if we do not see similar policies implemented by other Chinese IT operators soon.

If the campaign against US technology companies continues to gain momentum, the eight named firms will face tremendous operating pressures in the months, if not years, to come. Some are drawing comparisons between Cisco and Google, which moved its search engine from mainland China to Hong Kong in early 2010 due to confrontations with the Chinese government on Internet censorship. However, the two cases are fundamentally different. China censored Google and banned Facebook and Twitter use for fear that they could stir social unrest; a fear that was perhaps enhanced by technology’s prominent role during the Arab Spring,

By contrast, Cisco and Microsoft are part of a different story. Both had maintained good relationships with the Chinese government, especially Cisco. In fact, upon entering the Chinese market in the mid-1990s, Cisco helped many local governments build out their IT infrastructure and has consistently worked to improve the entire system over the past two decades. The perceived cyber security and espionage risks threaten this position now. Chinese state media have already flagged equipment including switches, routers, servers, conference call systems and cables – to name a few – which may pose a security risk.

A broader campaign against US technology firms could impact the presence of other US firms too, including companies in the supply chains of the Eight Warriors and other firms which Chinese logic dictates are similarly susceptible to cyber threats from Western government infiltration. Fearing similar reprisals if they cannot ‘prove the negative’ (that they are neither explicitly spreading “universal values” nor covertly facilitating cyber espionage), the number of US firms seeking to establish a business presence in China may decline. Such a scenario has obvious disruptive implications for the operating outlook for many western firms. In light of such scenarios, it is important to look for circuit breakers that could prevent the entire US-China (or western-China) investment relationship from blowing a fuse.

One such circuit breaker is that there are major technical issues for Beijing in shifting away from the likes of Cisco to ZTE and Huawei: the use of Cisco’s equipment and network is just too extensive in China to eliminate in a short time period, if ever. The official Global Times already has an answer to this problem: “Learn from the United States,” an article said, comparing the eight guardian warriors to the eight-nation alliance that intervened militarily in China more than a century ago. “Collaborate with Huawei, ZTE and companies blocked in the US…to accelerate a replacement strategy for national information infrastructure and core products in critical services.” However, for the time being, such anti-foreign alliances are the ramblings of state-run newspaper editors, not the clear thinking of industrial engineers.

Second, even if a de-Cisco campaign is technically feasible, superior policy by Chinese leadership could act as a more enduring circuit breaker. Such a leadership would embrace policy which tempers current anti- US tech sentiment in view of the fact that pushing foreign firms out of the Chinese marketplace cannot meaningfully induce economic benefits or national security in a globally connected world. In fact, such policy is almost certain to damage China’s economic and security interests, by radicalizing foreign trading partners who may be less willing to engage positively with China across a wider portfolio of interests.

China is not alone in debating the apparent vulnerability that comes with globalization. In this case, Beijing is understandably reacting to an alleged American surveillance capacity that exceeds what anyone – including the American people– believe current IT infrastructure could enable. But given that the US is embedded in mutual defense and security alliances with nations representing nearly 70% of the world economy, while China only has loose alliances with North Korea and Pakistan, Beijing would probably be the biggest loser if an anti-US tech campaign goes into full swing.