The Making of a G7 Summit

Group of Seven leaders will have a broad agenda when they meet in Cornwall on June 11-13. But much of their attention will be focused on an industrial giant that is not in the room: China.

Leaders from the Group of Seven (G7) and four guest countries meet for a summit in the UK on June 11-13. Though the agenda will be expansive, considerable attention will be focused on an industrial giant that is not in the room: China. G7 leaders have an opportunity to reset the narrative on growth prospects for the democratic world and show they are capable of collective action on areas of shared concern involving China. This note looks back at the early drivers of the G7 and what we might see this time.

The leaders of the G7 industrial nations—Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the US—plus guests Australia, India, South Africa and South Korea will gather on June 11-13 in Cornwall, England for their 47th meeting since 1973. This will be the first trip abroad for Joe Biden as president, and after the G7, he will travel on to Brussels for NATO and EU-US summits, and then to Geneva for a meeting with Russia’s Vladimir Putin. The G7 was born as a forum for collective action by market democracies on economic problems. It lost relevance to the Group of Twenty (G20) during the global financial crisis as the economic scales shifted toward big emerging nations. By trashing the G7 process, Donald Trump deepened doubts about its future.

But the meeting in Cornwall is important. Leaders plan to assert the relevance of their $40 trillion democratic marketplace and their agility as a like-minded caucus relative to the G20, which includes authoritarian countries like China and Russia. A productive G7 meeting would demonstrate that market democracies are alive and well, capable of working together, and taking the initiative in international leadership. In addition to managing the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change, a signature focus of this meeting will be China: this could be a watershed moment for coordinated market democracy action in the face of growing concerns about Beijing’s behavior. After years of alienating allies with gratuitous belligerence, Washington will be aiming to strike a balance with them on China.

In this analysis, we consider what G7 members might accomplish in Cornwall and how Beijing and markets would respond to a more unified democratic market community.

What the G7 Was Made For

The G7 started as an industrial democracy caucus in response to the 1973 oil shocks. From inception, it was a club for leaders to get to know one another to facilitate collective action on economic problems. Early on, it was a very private affair, with the most important work done outside the official agenda and often without public outcomes. There were exceptions—notably action to coordinate exchange rate policies, including the Plaza and Louvre accords in the 1980s (both signed by less than the full G7). The group was most valuable filling in where international regimes were missing or unreliable. Its focus broadened over the years to include political and security affairs.

The G7’s influence was eclipsed by the rise of broader caucuses such as the G20, which started in 1999 but became an influential forum for leaders of the world’s biggest economies (19 plus the EU) in 2008, in recognition of the importance of China and others in responding to the global financial crisis, and the view that international governance should be more inclusive. This shift to a broader group, including less market-oriented and less democratic members, was predicated in part on expectations for systemic convergence. Some observers declared at the time that the G7 process had reached its logical conclusion and that it may be time to bid it a fond farewell. A decade later, Donald Trump made a mockery of the G7, refusing to support a joint communique and lashing out at host Canada in 2018, then squandering an opportunity to show leadership at the height of the pandemic in 2020 when the US held the rotating presidency.

Given this recent history, it might seem unwise to expect much from the G7 leaders meeting in Cornwall. But a number of factors have converged to give the group what could be a new lease on life. President Biden’s defeat of Trump and the internationalist Mario Draghi’s emergence as Italian prime minister have brought two outliers back toward the G7 center. This meeting will be Biden’s first trip abroad as president, underscoring his promise to reinvigorate America’s neglected alliances. Invitations to Australia, India, South Africa and South Korea show the G7 is serious about collaborating with other democracies. And most important, shared concerns about China (and Russia) are pushing the seven toward collective action. That does not mean they all see China through the same lens. But China’s assertive choices on a range of matters over the past year—including imposing sanctions on European lawmakers, academics and research institutions for speaking out on human rights in March—have energized the case for a coordinated response. Members have been enacting policies to push back against China for years. But further momentum hinges on better coordination.

What a G7 Step Change Could Look Like

If collective resolve on China is a test of market democracy resilience, how are we to grade it? There are two central questions to think about. First, can G7 leaders agree on a strong, principled communique that draws a bright line around values and norms and speaks directly to their shared concerns? And second, can they take concrete policy steps to implement such a vision?

A Non-Decline Narrative

In recent years a narrative has emerged, fueled by China’s swift containment of and recovery from the pandemic, that democratic systems are in decline while China’s tightly controlled one-party model is ascendant. Some elements of this story flow from simple math: China has 1.4 billion people averaging less than a quarter of G7 income levels, and it is natural to expect upward convergence. But the key question is whether liberal market democracies have a strong outlook, relative to China. If China’s share of the global economy is inevitably rising and that of the G7 inevitablyfalling, then our long-held assumptions about the power of open societies and markets will need to be adjusted. G7 leaders are keen to shift the narrative but have been on their back foot in the pandemic. They have been struggling to strike a balance between seizing the market opportunities that China presents and pushing back against its increasingly assertive behavior. Trump sowed distrust among allies by treating them as foes and cutting deals with authoritarian rivals – including China.

The first hurdle, therefore, to restoring optimism about the G7’s prospects is US credibility. President Biden must demonstrate that the United States is back and prepared to resume a leadership role—with humility. This will not be easy. He must persuade peers that the damage to US potential and power in recent years is being repaired, and the policies and politics needed to sustain growth are coming together. Biden needs to reassure partners that his foreign policy for the US middle class will not be at their expense. Tolerance for one another’s domestic political imperatives will be important, as will a message from Washington that policy toward Beijing will be fact-based and not driven by ideology. Helping Biden’s cause is America’s rebound from the pandemic. The OECD just projected that the US economy will grow by 6.9% this year and US employment increased by 559,000 in May. For the moment at least, Washington is operating from a position of economic strength.

Beyond rebuilding their own narrative, the other question is how far the G7 will go in speaking out against actions by China that they deem unacceptable. A chill has descended on the Europe-China relationship following tit-for-tat sanctions that have halted ratification of an investment agreement that, only months ago, was being celebrated in Berlin, Paris and Brussels. Ministerial meetings in preparation for Cornwall produced strong China language. The May 5 foreign ministers’ communique criticized Beijing on human rights, trade and cyber issues. On May 28, trade ministers called for action on industrial subsidies and state-owned enterprises (without naming China) and set the stage for data exchanges on forced labor practices like those making headlines in China. Indirectly, they also called for an end to China’s “developing nation” status at the WTO. Finance ministers met on June 4-5 and were more reserved on China. However, they did underscore their commitment to market-determined exchange rates and the reduction of excessive global imbalances, putting down a marker for leaders on the role of the renminbi in contributing to China’s persistently huge trade surpluses. Finance ministers also called for more transparency and multilateralism on development finance, which should be read as a call for China to cease using financial diplomacy in the way it has.

If the G7 leaders’ communique reiterates what ministers have already said, this would already be seen as a demonstration of unity and resolve. Whether the other guests in Cornwall—Australia, India, South Africa and South Korea—will be prepared to endorse the communique is another question. All have their own China issues: border clashes for India and a trade war for Australia. However, India has a longstanding aversion to aligning itself too tightly with western countries; South Korea has close economic ties to China; South Africa benefits from Chinese investment; and Australia also has a lot to lose if it does not resolve its tensions with China. One of the G7 initiatives under discussion is an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), but even a strong outcome there is unlikely to match Beijing in terms of financial might.

Commercial Consequence

G7 members are also negotiating specific policy commitments. From the ministerial statements issued in the run-up to the leaders meeting, we can see that a wide range of steps are being discussed, some with China in mind, but not all aimed explicitly at China. Below are some areas where collective action is possible:

- Forced labor: Go beyond technical consultations, toward collective restrictions on imports tainted by forced labor, with insistence on supply chain auditing.

- Subsidies: Create a working group to harmonize and upgrade G7 member rules on industrial subsidies, especially as they benefit state-owned enterprises.

- International coal finance: Commit to end G7 financing of coal projects and phase out support for all fossil fuels by a certain date, while calling on China to do the same.

- Industrial policy: Create a working group to harmonize efforts to offset the negative impact from Chinese economic policy while avoiding G7 industrial policy misalignment.

- BRI alternative: Announce a G7-coordinated sustainable and inclusive infrastructure financing program to rival China’s BRI.

- Exchange rates: Create a G7 technical group to evaluate China’s exchange rate practices in light of its elevated and persistent current account imbalances.

- Economics and security: Create a working group to increase alignment on investment screening, export controls and other policies to protect technology and critical activity.

- Supply chain resilience: Create a working group to coordinate approaches to supply chain resilience, including diversification and re/near-shoring.

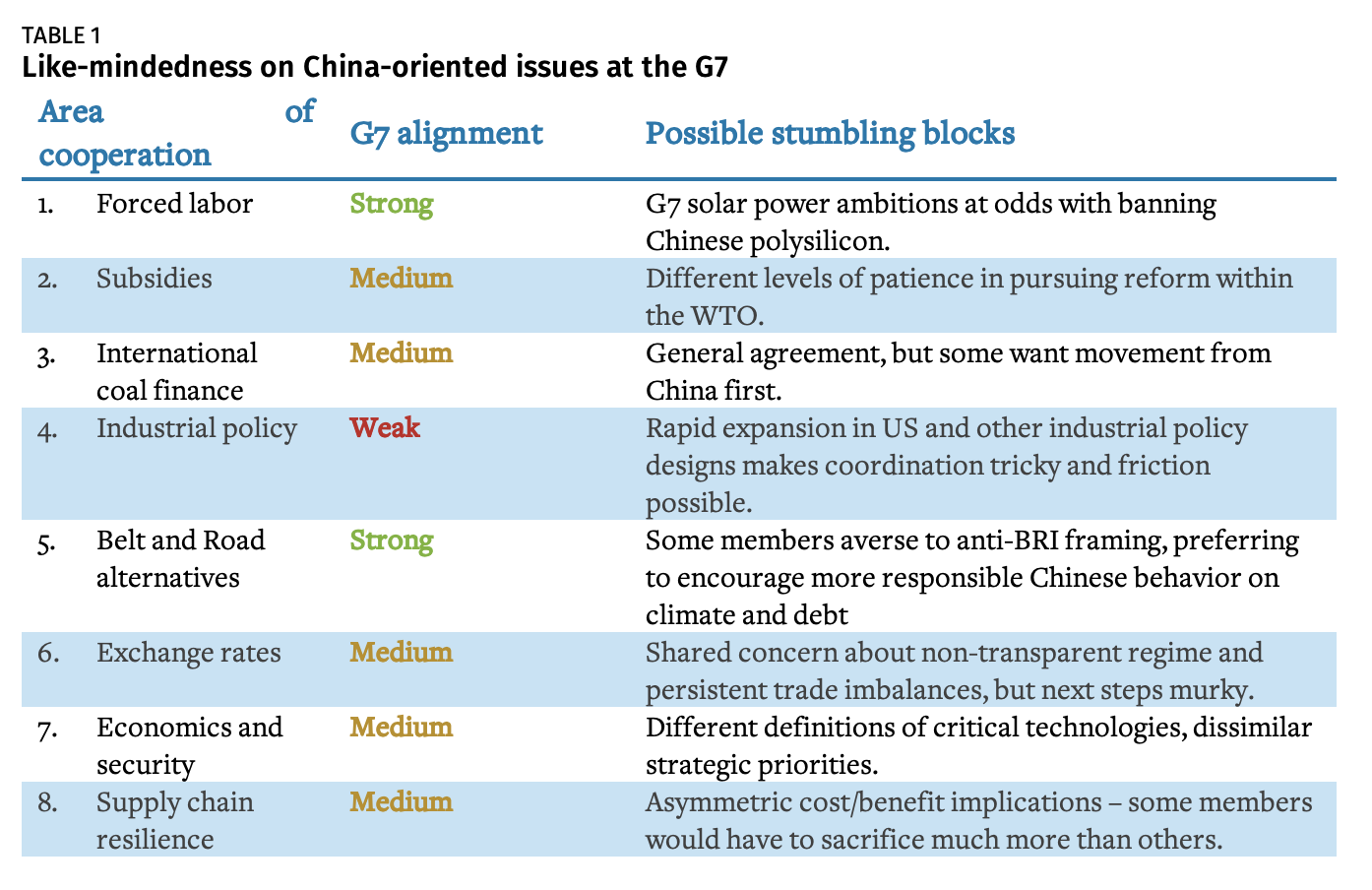

Table 1 provides a summary view of the degree of alignment on these issues within the G7 community. On some, there is a high level of agreement and conditions may be ripe for harmonization. On other issues, notably around industrial policy, the summit will be a chance to learn from one another—and perhaps lay the groundwork for coordination to reduce potential areas of friction. Cooperation does not have to mean full alignment.

How Beijing – and Global Markets – Could React

China will bristle at coordinated G7 action. Beijing tries to compensate for its lack of formal alliances by playing countries off against one another and emphasizing bilateral engagement over multilateral forums it cannot control. In recent months China has ratcheted up the pressure on some countries (Australia and Sweden, for example) in order to discourage others from taking principled stands or joining collective efforts. But it is difficult to credibly threaten everyone simultaneously. G7 action on China may therefore trigger targeted Chinese charm offensives rather than more punches. A recent Chinese leadership meeting foreshadowed as much: President Xi instructed colleagues to create a “trustworthy, lovable, and respectable” image for China abroad—perhaps a sign that Beijing is rethinking its “wolf warrior”, better-to-be-feared-than-loved, approach of recent years.

This may be more of a shift in advertising strategy rather than a change of product; nonetheless it shows that Beijing realizes that new tactics are needed. Beijing’s rhetorical response to a strong G7 summit will no doubt include a broadside against “Cold War era” thinking. But expect Beijing to take a more flexible approach going forward to try to cultivate the perception that US-China relations are on the upswing.

Market reaction to a robust G7 outcome on China is likely to depend in part on China’s response. If Beijing switches to a more balanced approach in an effort to undermine a balancing coalition, expect markets to be encouraged. Some G7 signals could give markets pause, however. For instance, any comments about China’s reliance on an undervalued currency to spur exports and a broader recovery would surely get the attention of the foreign exchange markets.

Conclusion

Preparations for Cornwall raised expectations of collective action on concerns about China. Preliminary indications point to a meaningful outcome. That would reflect a new US willingness to tone down its China bluster, European and Japanese willingness to take stronger stands than seemed likely at the start of the year, and thus a changing international environment.

What has been missing from the China policy debate in G7 and other democratic countries in recent years has been rigorous thinking about the desired end-state. The G7 message in Cornwall will be a crucial variable in that equation. If leading market democracies demonstrate that they are willing to compromise in order to tackle their concerns about China from a common position of strength, a better set of outcomes is possible. G7 unity would force China to be more attentive to international sentiment.