India’s COVID-19 Response: Energy Sector Reforms

Prime Minister Modi is using the political opportunity created by the pandemic to push through stalled reforms of the energy sector.

India has no plans for a Green New Deal to ameliorate the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, the Narendra Modi government has been belt-tightening at both the central and state government levels. This has not diminished a long-standing desire to make renewables and natural gas the dominant energy sources of the country. Prime Minister Modi is using the political opportunity created by the pandemic to push through stalled reforms of the energy sector. The nature of these reforms indicates a desire to ensure energy shifts are driven largely by market forces and regulatory action rather than state outlays. Together, these have meant a continuing incremental and fragmented response to curtailing greenhouse gas emissions.

The government’s overriding reform priority is to try to bring an end to the chronic financial problems of the electricity system. Its draft electricity bill proposes an end to cross-subsidies and depoliticized distribution companies and will face considerable political opposition. Sectorally, the drop in solar prices has revived investor interest. The coming together of a natural gas market continues to be encouraged. One complication is the adoption of protectionist measures to inhibit Chinese imports and boost domestic industry. This has already meant stiff tariffs on solar modules and cells. It has also led to moves to encourage private coal mining to reduce imports. In the past few weeks, possibly because India assumes the chair of the G-20 in 2022, the Modi government has begun to paint a bigger picture with talk of a regional solar grid and a global solar bank.

Electricity bill reforms

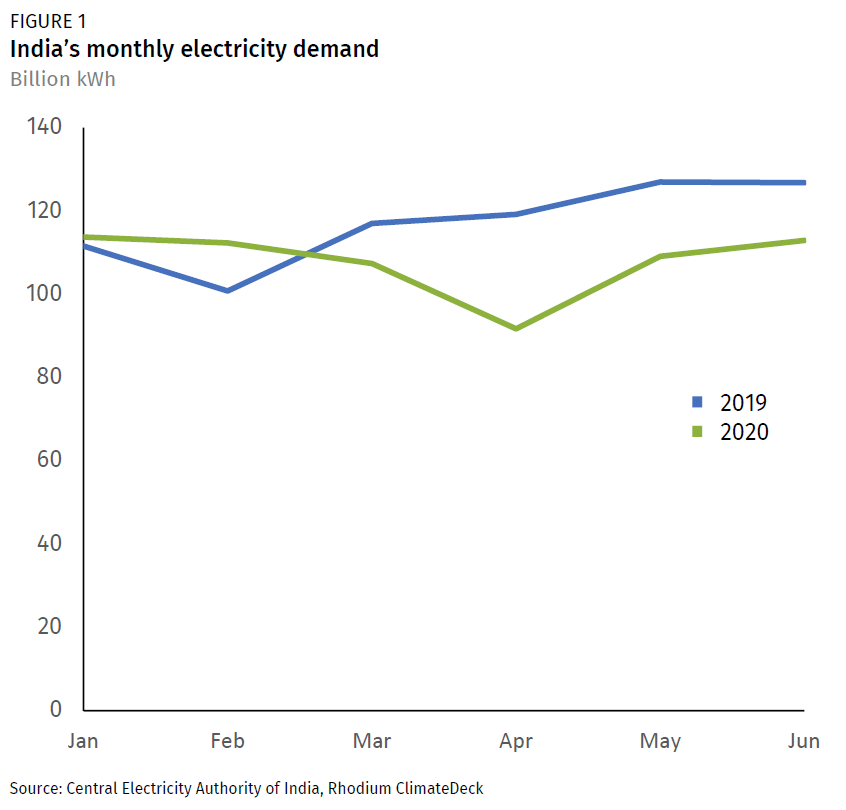

As the lockdowns reached their peak this April, India’s power demand dropped by a quarter compared to 2019 levels (Figure 1). Though power demand recovered to 90% of normal demand in June, the existing financial difficulties of the distribution companies have only worsened. The government’s overriding reform goal is to bring an end to the chronic financial problems of the electricity system.

The Modi government’s most ambitious use of the political space created by the pandemic is a plan to push through a new amendment to the Electricity Act 2003. The draft electricity bill is the latest attempt to resolve a recurring problem facing the power sector—the huge losses created by the gap between the cost of electricity production and the price that state-owned distribution companies charge their customers. The distribution companies charge too little because of populist pressures and the result is a state of quasi-insolvency that cripples the power sector. A labyrinth of subsidies and convoluted pricing policies to mitigate this financial burden infest the sector and scare away investment, attract politicking, entrench inefficiency, and inhibit innovation.

The new bill tries to lay the basis for a more financially sound energy sector that would, in turn, facilitate a more carbon-friendly energy policy. The bill’s main goals are to end a system of cross-subsidization, depoliticize the state electricity boards, choose more independent board members and make a still-to-be-announced national renewable energy policy the organizing principle of the power sector at a later date. The bill has engendered strong opposition from state governments and labor unions who fear losing the authority to set tariffs, to target subsidies to interest groups, and the eventual privatization of the distribution companies. The Modi regime has announced plans to privatize a few of the smaller distribution companies as a test run. Getting this bill passed in the upper house of parliament, where the ruling party lacks a majority, will require spending considerable political capital. The next parliamentary session is currently scheduled to start sometime in late August.

Protectionist measures in the solar sector

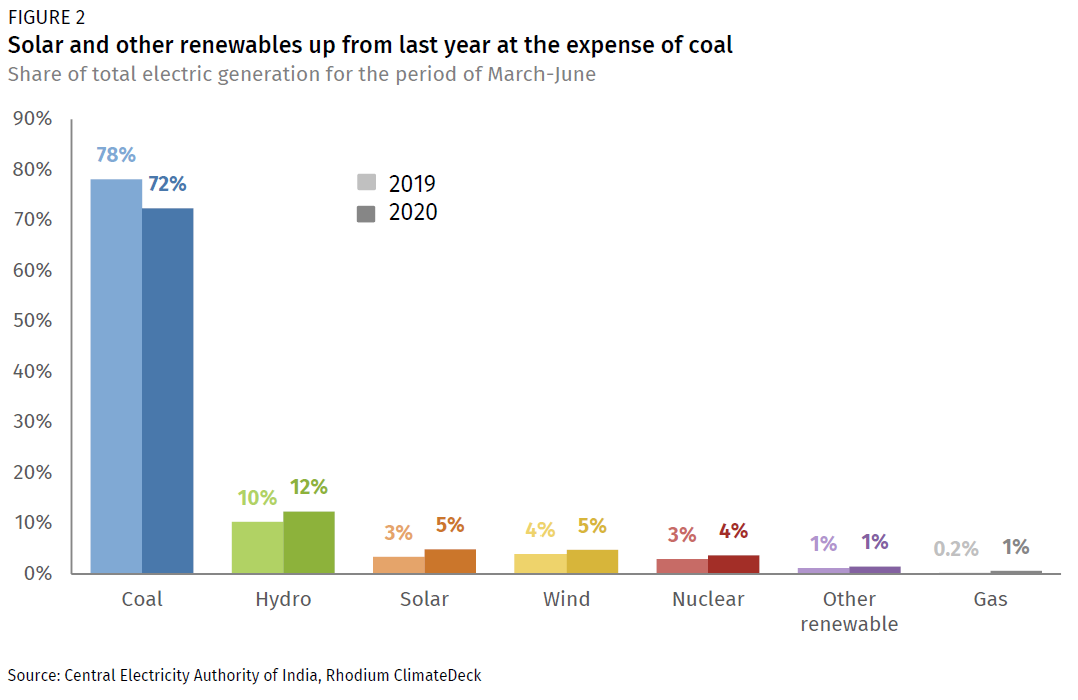

Solar power has done well during the pandemic. Renewables showed their ability to handle grid volatility during the crisis, ending long-standing claims to the contrary. From March to June this year, solar generation increased 23% from 2019 levels (despite an overall drop in electric generation of 14% year-on-year), boosting solar’s share of total electric generation from 3% to 5% (Figure 2).

The cost of solar power fell to a record low of Rs 2.36 (~3 US cents) per kilowatt-hour during a bidding round in early July, a consequence of technology and a flood of foreign capital into the sector. The total of private equity investments, mergers and acquisitions, and listed debt placements in Indian solar and wind energy has returned to late-2019 levels despite the present recession. The financial crises that afflicted the sector earlier have been mitigated with the introduction of more flexible supply contracts and tiered payment security mechanisms. India looks likely to come near its stated goal of 175 GW of renewable power by 2022, roughly double its present installed capacity. Yet when it comes to finances and the regulatory environment, the renewables sector, especially solar, is looking healthier than it was in 2018-19.

This is not wholly about market conditions. Solar and other renewables are under a “must buy” category for distribution companies, meaning they have a mandatory renewable energy purchase requirement. With the solar power price having fallen and storage improvements promising to reduce wheeling costs, buyers are more willing to fulfill this obligation. In any case, penalties on large power users and purchasers who try to circumvent their renewable energy obligations are likely to be increased. There are also plans for a green power exchange to allow for a renewables spot market, increasing demand and lowering prices for green energy. Some skeptics argue the real cost of solar power, once new projects start to include storage batteries, will prove unattractive to distribution companies.

What has also increased is the infusion of economic nationalism in India’s solar policy. The recession and recent border clashes with China have led the Modi government to extend a 15% tariff on imported solar modules until July next year. The government claims the tariffs will only slightly increase the cost of solar power, but environmentalists warn modules will be nearly a third more expensive. Another problem for this “Made in India” bias is domestic capacity constraints. While India can probably manufacture enough modules, it will need to massively ramp up cell production, while wafers will be imported for the foreseeable future.

In line with what it is doing in other strategically important parts of the economy, the government is moving to promote a national champion in solar: the Adani Group. This is a company whose previous energy forays have been in coal and gas, including trying to develop the controversial Carmichael coal mine in Australia. Today, the company’s owner speaks of ending all Chinese cell and module imports into India. The Modi government is still encouraging foreign financial investment in solar projects. Its nationalism is reserved largely for China and component manufacturing.

Consolidating the natural gas sector

The oil sector, once an Indian obsession, has ceased to be strategic. Despite the recession, taxes on diesel and petrol continue to increase. The Modi government is seeking to sell off much of the state-owned oil sector to private firms, domestic or foreign, and wants future investment in this field to be funded from outside the state treasury. The unspoken view is that the country’s oil-related assets are best used to raise funds for more future-oriented economic activity. The government allowed the sale of the second-largest private Indian oil firm to Russia, wants to privatize the second largest state-owned oil firm, and has approved the sale of a large stake in the largest private oil and gas firm to a foreign buyer.

Consolidating India’s fragmented natural gas, on the other hand, remains a government policy focus. COVID-19 has not stopped a steady push to have gas replace coal-fired power for industry, end the subsidy regime for nitrogenous fertilizers, promote gas use for cooking, and make it available for fleet cars and public transportation. Gas-powered turbines earned many points when they matched renewables in providing grid stability over the past few months. The government hopes lowered gas prices may make the existing but idle turbines viable again.

A number of reforms have moved the country closer to market-determined gas pricing and the building of a nation-wide pipeline and distribution network. The government set up a gas exchange in June to create a domestic spot market. It has accelerated plans to spin off the state-owned Gas Authority of India Limited’s pipeline network as a separate firm. A series of reforms are designed to enhance domestic demand, including delicensing the opening of LNG outlets, expanding cooking gas welfare schemes, increasing the city gas pipeline network, and cutting domestic prices to align with the fall in global gas prices.

The biggest demand change would arise from the passage of the draft electricity bill mentioned earlier. The end of the cross-subsidy structure would lower industrial power prices, allow factories to shop around for a power source with many of the larger, energy-intensive sectors expected to opt for imported gas.

One gamble is the decision to slash gas prices by over a quarter in March. The government has said it wants to bring down industrial power costs by 36% on average to make India more competitive in manufacturing. Lowered gas prices are a major element of this strategy. A number of local gas players have complained this would make infrastructure spending in the sector unviable. And it makes the financing of the planned pipeline expansion more problematic. If other reforms lead to a surge in gas use by energy-intensive industry, possibly the greater demand would compensate for the price cuts.

Cautious on coal

The government continues to tweak policy to hobble the growth of coal-based thermal power. The recession and prioritizing renewables in the grid means that plant load factors among many thermal plants have fallen to as low as 45%. Over the period of March to June this year, coal generation declined 20% compared to 2019 levels, faster than the 14% decline in total electric generation year-on-year (see Figure 2, above).

However, the government is so far unwilling to pursue more aggressive action against coal. There seems to be concern that other fuels are not ready to fill in any resulting gaps in the power situation. The recession also means Modi is sensitive to disruptions that would cause immediate job losses and social unrest. On a purely commercial basis, it makes little sense to keep a lot of older coal plants working, especially when solar and gas prices have fallen so low. Political sensitivities seem to be driving this piecemeal approach.

There has been tightening of pollution norms and redirecting of the stimulus to cleaning up existing coal plants. The government’s main policy move has been to take aim at India’s rising coal imports. It plans to auction off 41 coalfields to private producers. As this only offsets a similar amount of imported coal, this does not add to overall carbon emissions while creating jobs at home. The most likely buyers would be industries like medium-sized sponge iron plants too isolated to ever have a gas pipeline connection. Yet these new “captive” coal mines would concretize carbon-intensive energy use with a swathe of firms. The assumption is larger plants and listed firms would turn to gas as a power source—but this would require India to move several steps further on gas reforms.

Climate and energy diplomacy

India will easily fulfill its targets under the Paris Agreement but is not investing further in the climate agreement until it sees the results of the United States presidential election. New Delhi is also watching how the prime ministerial succession shapes up in Japan, given the massive economic support Modi has received from Shinzo Abe the past several years. Modi held a virtual summit with the head of the European Union in mid-July to restart a COVID-19 stalled effort to work more closely, with climate topping the agenda. However, official assessments of the impact of climate change on India are bleak, which is one reason the government has been promoting its Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure.

In June, the prime minister called for a One Sun, One World, One Grid international renewable energy grid that in its initial phase would connect India’s grid to Southeast Asia and eventually West Asia and Africa. The World Bank is currently putting together a feasibility study on it. In theory, this would elevate the Indian-backed International Solar Alliance from a cluster of unconnected solar projects spread across many countries, to a rules- and standards-based energy coalition. There is considerable skepticism about the likelihood of this getting off the ground. Trans-border energy grids require a high degree of political trust and India has struggled to get even its smaller neighbors to agree to grid integration. In July, the government also proposed a World Solar Bank, the details of which remain fuzzy.

India assumes the chairmanship of the G-20 in 2022. Modi, personally invested in making this a diplomatic success, has already indicated he wants climate to be front and center. With the international system fissuring rapidly, this may prove difficult, especially if India and the West are unable to find a new equilibrium in relations with China.