New Realities in the US-China Investment Relationship

A sea change in investment flows suggests opportunity, but also a pressing need for policy leadership to ensure a success story does not turn into a new grievance.

For decades, foreign direct investment (FDI) flows between the US and China were a one-way street: American multinationals invested in labor-intensive manufacturing and consumer-oriented operations in China, but Chinese firms had neither motive nor capacity to invest in the US economy. In the past 5 years this situation has changed profoundly, as Chinese investment in the US took off, and, by most measures, now exceeds flows in the other direction. This sea change suggests opportunity, but also a pressing need for policy leadership to ensure a success story does not turn into a new grievance.

Key Findings:

- After 5 years of rapid growth, Chinese annual FDI in the US now exceeds FDI by US companies into China by most measures — including China’s own official statistics.

- These investment flows bring benefits for Americans, including job creation and a more competitive consumer market, and have the potential to be a major contributor to stronger US-China relations.

- However, this turning point calls for increased policy attention, including US leadership in support of continued openness and timely Chinese investment liberalization to keep pace with changing trends on the ground.

Recommendations:

- Chinese and US officials need to jointly acknowledge the changed pattern in two-way FDI flows. Failure to recognize new realities will cause confusion and aggravate existing perception biases on both sides.

- In light of the data trend, leaders must correctly diagnose the threats to two-way investment growth. These risks include the possibility that the US investment screening process could be stretched beyond protecting solely national security, and that China’s steps to open its foreign investment regime could occur too slowly and half-heartedly to forestall investment protectionism abroad.

- Reality-driven expectations will naturally fall on the ongoing US-China bilateral investment treaty (BIT) negotiations. Since the US imperative is not to open, but simply to stay open, the bold progress in these talks must principally come from the Chinese side, including a heavily trimmed down “negative list” of sectors to be partly or wholly excluded from liberalization.

A joint RHG-US Chamber of Commerce report. Download the Full Report [PDF]

A Sea Change in Bilateral FDI Flows

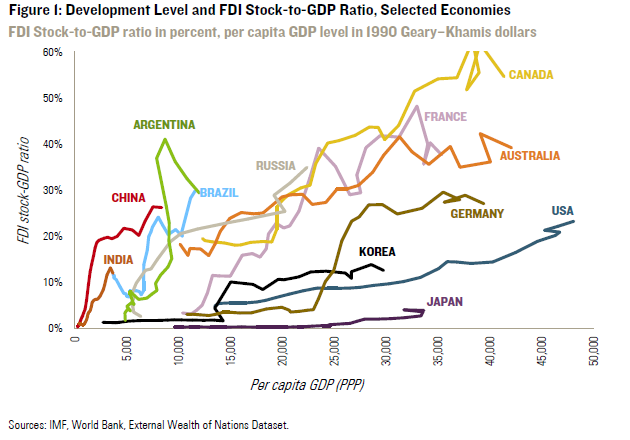

Building on Deng Xiaoping’s insights about the importance of foreign capital, China embraced FDI early in reform to boost economic growth. In fact, China has embraced FDI at a lower level of per-capita GDP than any other major economy in history, with an inbound FDI stock of $2.4 trillion at the end of 2013 (Figure 1). FDI has been a significant ingredient of China’s economic success story and a major driver of China’s integration into the global economy.

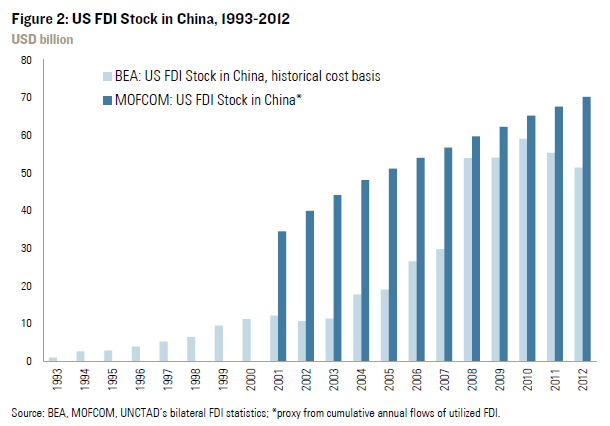

While the majority of FDI into China has come from Asian economies, American companies seized this opportunity as well and invested tens of billions of US dollars in China over the past three decades. Official statistics from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) and China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) show that US firms currently have an FDI stock in China of anywhere between $50 billion and $70 billion.

The BEA’s figures show a steady increase of US FDI stock in China to around $50 billion to $60 billion, but with slowed growth, and even dips, in recent years. Unfortunately, MOFCOM does not provide detailed figures on inward FDI stock, but international organizations use cumulative inflows of utilized FDI as a proxy, which show an inward FDI stock from the US of around $70 billion (Figure 2).

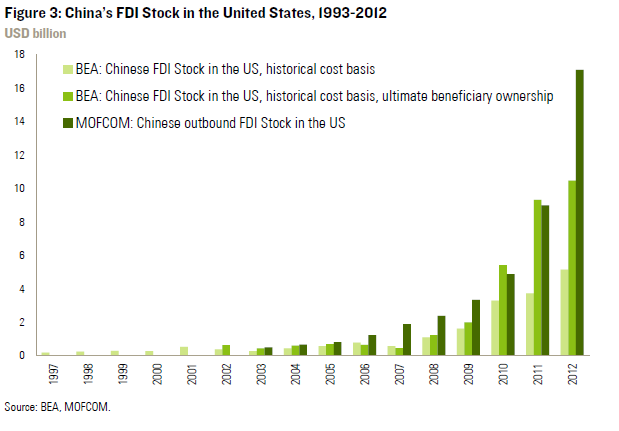

Chinese investment in the US during this period was mostly limited to the purchase of Treasury bonds and other securities by the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) and other sovereign investors tasked with recycling China’s gigantic foreign exchange reserves, which have now reached almost $4 trillion. These official holdings accounted for well over 90% of Chinese capital invested in the US in the past decade. FDI flows to the US remained small, as Chinese firms had neither the incentive nor the capacity to run operations in America. Official data points confirm that China’s FDI stock in the US was negligible for most of the past two decades (Figure 3).

Since 2007, this reality has changed. BEA’s data on Chinese FDI stock in the US, based on International Investment Position (IIP) methodologies, show an increase from $585 million to $5.2 billion in 2012. However, this measure only counts FDI coming directly from China and omits flows which are routed through third countries, a practice used extensively by Chinese firms due to capital controls and inadequate legal and financial infrastructure at home. A second BEA dataset, that compiles inward FDI stock on an “ultimate beneficiary ownership” basis (tracking the flows back to the ultimate parent company), puts Chinese FDI stock in the US at more than double that amount by the end of 2012 ($10.5 billion). Official data from China’s MOFCOM show an even more pronounced increase in the stock of Chinese FDI in the US, from $1.9 billion in 2007 to $17.1 billion in 2012.

In summary, while there are significant discrepancies between official datasets, available data points suggest that, over the past five years, the US FDI stock in China has been stagnant or even declining, while China has quickly ramped up its FDI in the US. This has been driven by a maturing Chinese economy, a more open and supportive policy environment for outbound FDI in China, and firms’ increasing appetite to bite off advanced economy technology, brands and consumer capabilities.

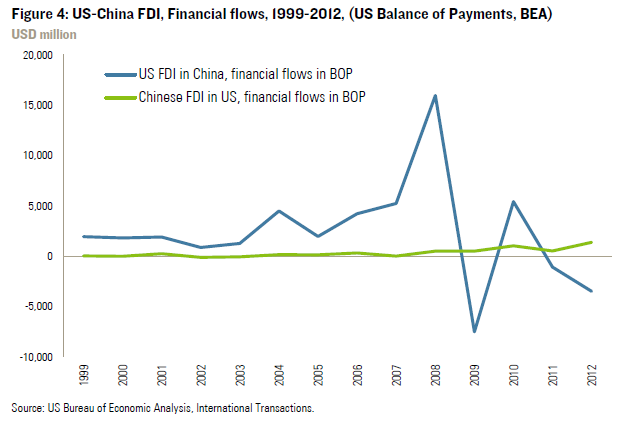

Available data points that describe annual FDI flows between China and the US confirm this sea change. They show that Chinese FDI in the US has not only grown rapidly since 2008, but that Chinese inflows now exceed American FDI flows to China.

The first dataset presents the BEA’s figures on FDI flows between China and the US based on Balance of Payments (BOP) methodologies. It shows that, in both 2011 and 2012, Chinese FDI flows into the US exceeded flows in the other direction (Figure 4). However, there are two problems with this dataset. First, it only records flows coming straight from China, which means it neglects Chinese FDI coming through Hong Kong and other locations. Figures regarding annual flows on an ultimate beneficiary owner principle are unfortunately not available. Second, the data show great volatility in recent years, reflecting intra-company flows and the capital allocation decisions of corporate treasurers based on exchange rate expectations, tax holidays and other factors. In some years, negative flows were recorded, indicating that firms have pulled money back from China due to concerns about exchange rates, the state of China’s economy, or funding needs outside of China. Preliminary data by the BEA indicate a swing back into positive territory in 2013, against the backdrop of economic recovery in China and changing currency expectations.

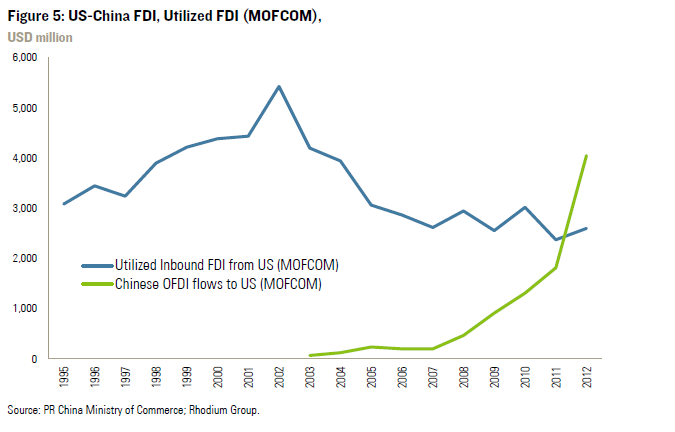

MOFCOM’s FDI statistics have traditionally been problematic too, as they are based largely on administrative project approvals and often only track the first, and not final, destination for outflows. For example, MOFCOM registers more than 80% of China’s outward FDI stock in Hong Kong and offshore financial centers. However, their data compilation has improved somewhat in recent years, and now shows FDI flows to the US surging in recent years. According to MOFCOM, the US became the second biggest target for Chinese outbound FDI in 2012, after Hong Kong, beating other Asian countries and major resource exporters, including Australia and Canada. At the same time, MOFCOM data show that FDI by US companies in China has levelled off from a peak of $5-6 billion in the early 2000s to $2-3 billion annually in recent years. In 2012, Chinese FDI to the US exceeded flows in the other direction for the first time, according to MOFCOM (Figure 5).

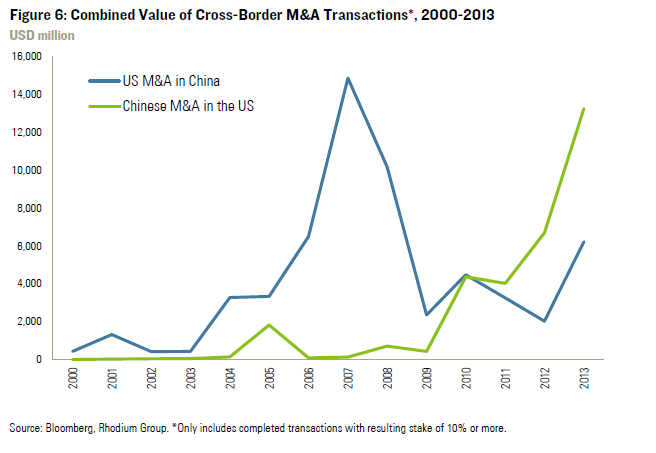

Finally, because official data are problematic, we can also examine transactional data to track bilateral investment flows. Rhodium Group’s China Investment Monitor, which tracks Chinese greenfield and M&A transactions, shows that the value of Chinese FDI in the US grew, from less than a $1 billion annual average before 2008, to more than $14 billion in 2013. We do not have the same data for US FDI into China, but can rely on readily available data on M&A transactions as a proxy. Looking at completed M&A transactions with a resulting stake of 10% or higher (which is the standard threshold for defining FDI), the crossover occurred in 2011, with Chinese M&A value exceeding flows in the opposite direction (Figure 6). One important caveat of using only M&A data is that greenfield FDI is a more important component of US FDI in China than the other way around.

In short, while there are discrepancies, caveats, and volatility in bilateral FDI statistics, available data points show that a sea change has occurred in recent years. American FDI stock in China is still significantly higher than China’s FDI stock in the US, but annual Chinese FDI flows into the US have grown faster than the other way round and now exceed US annual flows to China by all available measures.

Implications for US-China Relations

The evolution from a one-way to a two-way investment relationship is good news for the US and can help stabilize and deepen US-China relations. For American consumers, FDI from China can help maximize product choices, lower prices, and promote innovation. For US firms, FDI from China means better prices for those looking to divest assets, a new pool of potential partners, and greater compliance by Chinese competitors with global norms. In local communities, FDI from China can bring or sustain jobs, tax revenue, R&D investment and knowledge spillovers.

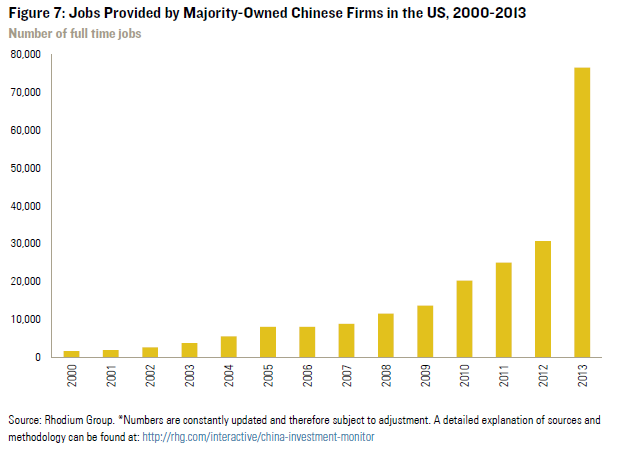

While Chinese companies have only been present in the US market as investors for a short time, there already are some data points supporting these benefits. For example, we count that Chinese firms now have more than 70,000 Americans on their payrolls, a sharp increase from barely 10,000 in 2007 (Figure 7).

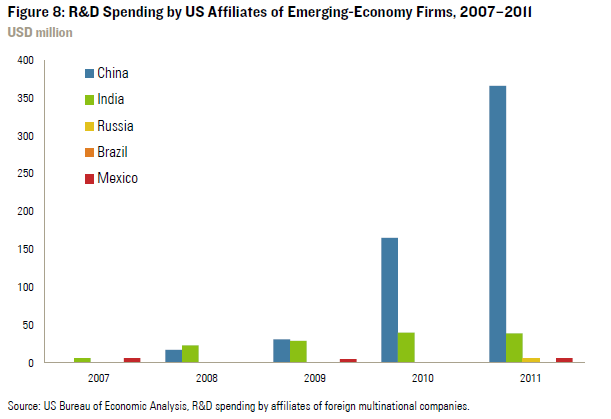

Local R&D spending by Chinese-owned firms in America has grown from virtually zero in 2007 to more than $350 million in 2011, and is probably significantly higher today (Figure 8). That’s still small compared to what established investor countries like Japan or Germany spend, but already much higher than other emerging economies, and on par with smaller Asian economies like South Korea or Taiwan. These aspects of China’s American footprint are a welcome change from the negative narrative of lost local jobs long associated with China.

At the same time, greater FDI from China amplifies some long-standing challenges and can inflame bilateral tensions if leaders do not act promptly. In the United States, the growth in Chinese transactions, existing asymmetries in market access, the role of state-owned enterprises and the shift in focus towards technology and higher value-added activities have amplified calls for expanded investment screening, beyond just national security concerns, to include some test of “net benefits”, similar to what Canada or Australia attempt.

This would likely invite more politicization of Chinese investment and threaten US leadership in investment openness, with uncertain economic or security benefits. US leaders must defend current openness, continue to limit screening to narrow security concerns and protect the efficiency of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS).

Chinese leaders face the challenge of not only reforming outbound FDI regulations to make it easier for private firms to invest overseas, but significantly speeding up the convergence of inward investment rules with more liberal nations like the US. China formally restricts foreign investment in many sectors, including those in which Chinese firms are now investing overseas (Figure 9), and applies other forms of formal and informal discrimination toward foreign firms as well. Absent change, growth of FDI into China will continue to slow, especially in services and advanced manufacturing sectors, and there is some risk of a backlash against Chinese investment abroad.

Outright reciprocity is not what the US is or should be asking for in FDI terms; reasonable people disagree about the right limits to cross-border capital flows, particularly at China’s development stage. However, as Chinese companies now compete head-to-head with local firms in open, overseas markets, indulgence toward this developing economy behavior is fading fast, and there is little logic in distinguishing between foreign and domestic firms with regard to investment restrictions. China therefore needs to move from an approval-based FDI system to a modern regime under which foreign investors receive the same treatment as domestic firms, both at the investment screening level and in terms of other reviews that can defeat investment openness, such as merger review under the Anti-Monopoly Law, with only narrow exceptions such as national security screening that does not encompass overly broad criteria such as economic security and social welfare.

Given that Chinese FDI in the US has surpassed US flows into China, the politics of these new realities are likely to change quickly. In this context, defending US investment openness to politicians who have grappled with a China trade imbalance for 20 years becomes untenable, and a backlash is a real possibility.

Recommendations

The sea change in US-China FDI relations in the past five years shows that businesses are already taking advantage of the opportunities presented by two-way US-China direct investment. Chinese and American officials need to keep pace with these new realities to sustain the success story for business interests and to add ballast to the overall bilateral relationship.

First, political leaders need to acknowledge these positive trends to overcome existing perception biases. The fast growth of Chinese outbound FDI, the lack of good data, and the heavy bias of media coverage toward a few troubled transactions have created misperceptions both in the United States and China. Americans need to better understand the drivers and impacts of Chinese investments and avoid knee-jerk reactions that have politicized a handful of deals in the past. Chinese leaders and executives need to overcome the misconception that they face a closed door in America. China’s own official numbers show what alternative indicators have made clear for some time: Chinese investment in the US is rising rapidly, and the US is welcoming these investments. It is time to catch up with this reality and refrain from political rhetoric that the US is closed to Chinese investment.

Second, leaders on both sides need to identify barriers to deepening two-way FDI and address them immediately. While there are many areas that need to be addressed– including the behavior and discipline of state-owned and state-supported enterprises, domestic IP ownership requirements, and overall transparency in investment regulation—the most urgent task is to sustain and expand investment openness. In the US, this means keeping the door to Chinese investment open, ensuring that the CFIUS process continues to work efficiently, and rejecting an expansion of investment reviews to consider economic benefit criteria.

In China, this means faster progress in modernizing the inward FDI regime and creating a level playing field for foreign companies. Chinese leaders have demonstrated an encouraging willingness to accelerate policy reform to open to foreign investment in the past year. The Third Plenum reform program and the most recent work report by Premier Li Keqiang acknowledged the importance of reforming China’s inward FDI regime, and new rules for a Shanghai Free Trade Zone are an incremental step toward equal treatment for foreign firms in China. In addition, China’s expressed interest in joining the Trade in Services Agreement (TISA) negotiations may signal a greater willingness to liberalize inward investment in services industries. Nonetheless, the rapid evolution of two-way FDI has outpaced these policy developments. Inward investment reform needs to be accelerated to catch up, rather than businesses being asked to slow down.

Expectations for progress on market access and related matters, including those referenced above, will naturally fall on the ongoing US-China negotiations over a bilateral investment treaty (BIT). The US imperative is not to open, but simply to stay open, so the movement in these talks must principally come from the Chinese side. Presidents Obama and Xi seized the opportunity to set these talks on a faster track last summer, and major progress toward completion will now be essential to demonstrate that both countries are aware of the new realities and eager to secure the benefits of two-way direct investment flows.

Therefore both US and Chinese proposals for negative lists of industries to be exempt or limited in terms of BIT coverage must be short and transparent, and any transition periods should be brief (certainly no longer than China’s self-assigned 2020 deadline for implementing its Third Plenum reforms). Anything less than a dramatic reduction in China’s draft negative list as a first offer in the BIT negotiations would be a severe disappointment. Indeed, Beijing should go further and phase out all industry restrictions lacking a clear explanation of why market competition cannot “select the superior and eliminate the inferior” to speed up economic restructuring – as President Xi Jinping personally called for at the Party Third Plenum in November 2013.

However, even in the best case BIT ratification and implementation would require at least two years, and the holistic reforms Xi Jinping is promoting to make the market decisive in China are expected to take six years. The expectations fostered by the new trend in two-way investment cannot wait that long. An early harvest of investment opening in important sectors is needed this year to sustain and promote continued investment deepening. With steps such as these China and the United States can demonstrate a powerful willingness to grasp mutually beneficial opportunities to strengthen bilateral relations. Indeed, accelerated policy cooperation to adjust to new economic trends and realities should be a hallmark of the new type of major power relations Beijing and Washington have sought to achieve.

References

Bloomberg L.P. 2014. “Mergers and Acquisitions by Chinese firms in the United States.” M&A data. Bloomberg Terminal.

Bureau of Economic Analysis. 1960–2014. “U.S. International Transactions, 1960–Present.” http://www.bea.gov/international/index.htm.

Bureau of Economic Analysis. 1977–2014. “Data on Operations of Foreign Affiliates in the U.S.” http://www.bea.gov/international/index.htm.

Bureau of Economic Analysis. 1980–2014. “Foreign Direct Investment in the U.S.: Balance of Payments and Direct Investment Position Data.” http://www.bea.gov/international/index.htm.

Hanemann, Thilo. 2014 Forthcoming. “Following the Money: Alternative Approaches to Tracking Chinese Outward FDI.” Conference paper, 21st Century China Program, UC San Diego.

Hanemann, Thilo, and Cassie Gao. 2014. “Chinese FDI in the US: 2013 Recap and 2014 Outlook.” Rhodium Group, January 7. /notes/chinese-fdi-in-the-us-2013-recap-and-2014-outlook.

Hanemann, Thilo, and Adam Lysenko. 2012. “The Employment Impact of Chinese Investment in the United States.” Rhodium Group, September 27. /articles/the-employment-impacts-of-chinese-investment-in-the-united-states.

Hanemann, Thilo. 2013. “Testimony before the U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission.” Hearing on “Trends and Implications of Chinese Investment in the United States,” May 19. http://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Hanemann%205.3.13.pdf.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 1993. “Balance of Payments Manual.” Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/bopman/bopman.pdf.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2009. “Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual.” Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/bop/2007/pdf/bpm6.pdf.

Lane, Phillip R., and Gian Maria Mileso-Ferretti. 2006. “The External Wealth of Nations Mark II: Revised and Extended Estimates of Foreign Assets and Liabilities, 1970–2004.” International Monetary Fund, Working Paper no. 06/06, March 1. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=18942.0.

Lane, Phillip R., and Gian Maria Mileso-Ferretti. 2007. “External Wealth of Nations Dataset, 1970–2011.” http://www.philiplane.org/EWN.html.

Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China, and State Administration of Foreign Exchange. 2012. “Outward Foreign Direct Investment Statistical Procedure.” http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/b/bf/201212/20121208507450.shtml.

Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China, and State Administration of Foreign Exchange. 2013. “2012 Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment.” Beijing: China Statistics Press.

Moran, Theodore H., and Lindsay Oldenski. 2013. “Foreign Direct Investment in the United States: Benefits, Suspicions, and Risks with Special Attention to FDI from China.” Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2014. “FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index.” http://www.oecd.org/investment/fdiindex.htm

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2008. “Benchmark Definition of Foreign Direct Investment—4th Edition.” http://www.oecd.org/document/33/0,3343,en_2649_33763_33742497_1_1_1_1,00.html.

Rosen, Daniel H. and Thilo Hanemann. 2009. “China’s Changing Outbound Foreign Direct Investment Profile: Drivers and Policy Implications.” Peterson Institute for International Economics, Policy Brief no. 09-14. http://www.iie.com/publications/pb/pb09-14.pdf.

Rosen, Daniel H. and Thilo Hanemann. 2011. “An American Open Door? Maximizing the Benefits of Chinese Foreign Direct Investment.” Asia Society, Center on U.S.–China Relations, May. http://asiasociety.org/files/pdf/AnAmericanOpenDoor_FINAL.pdf.

State Administration of Foreign Exchange, People’s Republic of China. 2013. “China Balance of Payment.” http://www.safe.gov.cn/.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2014. “Bilateral FDI Statistics 2014.” http://unctad.org/en/Pages/DIAE/FDI%20Statistics/FDI-Statistics-Bilateral.aspx

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2005a. “Expert Meeting on Capacity Building in the Area of FDI: Data Compilation and Policy Formulation in Developing Countries—Introduction to Major FDI Issues.” Accessed February 17, 2014. http://unctad.org/sections/wcmu/docs/C2em18p23_en.pdf.

Wilkins, Mira. 1989. “The History of Foreign Investment in the United States to 1914.” Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wilkins, Mira. 2004. “The History of Foreign Investment in the United States, 1914–1945.” Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.