An OECD For a New Era

Today, market economies are struggling to agree on a competition model with non-market statecraft again. Rather than invent a new institution, they should take a fresh look at this existing one.

September 30th, 2021, marks the 60th anniversary of the creation of the OECD—the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The organization was the post-WWII flagbearer for market economics, offering a positive vision of the benefits of cooperation among market democracies. By emphasizing analytical expertise to find pathways to policy alignment, the OECD achieved success and helped define the character of post-war liberal political systems in competition with authoritarian statism. Today, market economies are struggling to agree on a competition model with non-market statecraft again. Rather than invent a new institution, they should take a fresh look at this existing one.

A Market Economy Family Reunion

After a period of unilateralism, the US is again promoting international cooperation to address shared concerns. This will not always be the case, as the contretemps over submarine sales to Australia made painfully clear. But the return to market economy teamwork is real, and it comes at a crucial moment: advanced economies are dealing with questions that require active coordination. How to deal with non-market or authoritarian business partners? How to craft data policy, competition policy, investment screening, and other policy areas at the intersection of economic and national security?

Most importantly, what forum should market nations use to cooperate on these issues? The big-tent multinational organizations such as the World Bank, WTO, UNCTAD, and IMF each have important roles. But their inclusiveness has drawbacks too, particularly when members have fundamentally different views over the merits of market mechanisms versus state planning and economic authoritarianism. A few business associations – notably Germany’s admirable BDI – have moved out front to get their members thinking proactively, but most trade groups are keeping their heads down, waiting for national leaders to set the tune.

Market economies have begun caucusing in several venues to discuss novel concerns in an era of systemic competition, such as the G7 leaders meeting in Cornwall and the US-EU summit in Brussels this summer. The first ministerial-level meeting of a new US-EU Trade and Technology Council will convene in Pittsburgh on September 29, with an ambitious agenda to improve alignment in ten economic areas (see Sept 21, “Transatlantic Stress Test”). Like any new effort, that process will take time to gel, but already it has demonstrated seriousness in defining the agenda. These and other ongoing conversations like the US-EU-Japan trilateral dialogue on subsidies are an important step toward alignment. But each of these conversations involves just a subset of like-minded market economies.

Does a new forum need to be created? Before attempting that difficult chore, there is a good case to be made that the well-established, Paris-based Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is well-suited to manage the market economy conversation—and response— to today’s emerging concerns.

Why the OECD?

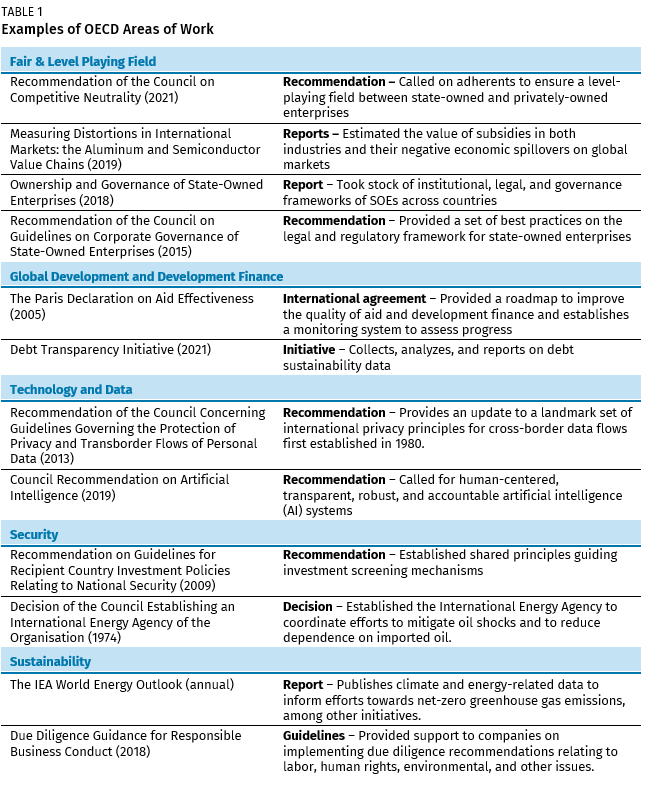

In 1948, the United States and Canada worked with eighteen European economies to form the Organisation for European Economic Coordination (OEEC). Just as NATO was a vehicle for shared security cooperation, the OEEC was the center for economic prosperity partnership in the democratic world.[1] With Europe facing the monumental challenge of rebuilding after the Second World War, the OEEC was tasked with administering Marshall Plan assistance. By the end of the 1950s, with European rebuilding on track, member countries redirected the OEEC to “promote the highest sustainable growth of their economies and improve the economic and social well-being of their peoples.” Rebranded as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in 1960, it expanded its membership and focused on growing global trade and investment. It took on new work on energy, governance, and global development. In the ensuing decades, the OECD built an impressive track record grappling with thorny economic topics among the industrial democracies (Table 1).

Today, the OECD has 38 member economies: upper-middle and high-income democracies generating over 60 percent of global output. The organization works with policymakers, businesses, labor representatives, academia, and other stakeholders to provide independent research and policy recommendations, facilitate information sharing, and establish international standards. In addition to its core membership, the OECD maintains partnerships with five non-member economies—China, India, Indonesia, South Africa, and Brazil—providing opportunities for regular dialogue. Thanks to its reputation for objective analysis, it has been tasked with developing reports, recommendations, best practices, and agreements on a wide range of issues.

The OECD has the features required of a forum to address the challenges posed by non-market economies. Its smaller roster makes it a more flexible organization than larger multilateral bodies. China, although not a voting member, is nonetheless a partner, creating opportunities for exchange without sacrificing principles. The OECD’s reputation for quality research and record on security, climate, and technology—all central to current debates—make it a compelling platform. Finally, its attachment to evidence-based work on economic, social, and environmental variables makes it a mostly apolitical shop.

Secretary-General Angel Gurría (2006-2021) focused his long tenure on making the OECD more inclusive. Some observers feared this could dilute credibility. Proponents of hard-hitting new research agendas sometimes had a hard time getting support from leadership. Gurria’s successor Mathias Cormann, a Belgian-born former Australian finance minister with a pro-reform reputation, has raised expectations since taking over in June 2021.

An Expanded Agenda

As the OECD secretariat enters a new era, the organization can play a greater role in bolstering shared norms and crafting a response to the challenges posed by non-market economies. Certainly not everything can or should be on the OECD’s agenda. Some issues—non-proliferation and arms control, for instance—are best left to other organizations. But there are many areas where the OECD is suitable to play a leading role. Many of these lines of work are not new to the OECD, but they would merit being strengthened further:

- Subsidies and other distortive economic practices: The OECD has successfully documented the negative spillovers into the global semiconductors and aluminum markets due to subsidies from China and other countries. Building on the EU’s lead in grappling with these problems using an anti-foreign subsidies instrument (FSI), the OECD can be a forum to share experiences in drafting and implementing anti-subsidies regulations, developing best practices on how these rules should be implemented, and documenting distortions in other sectors too.

- Industrial policy: Mounting competitive pressures from China and heightened concerns of an overreliance on Chinese supply chains have inclined OECD economies to deploy domestic programs to support home champions in critical technologies and sectors. In this context, there is a risk that these policies will raise trade and investment barriers, trigger wasteful public spending, or even cancel each other out. While other organizations such as the IMF have published research on the pros and cons of industrial policies, the OECD is the right forum to establish a series of best practices to prevent industrial policy from teetering into protectionism.

- Transparent and sustainable overseas infrastructure development: Developed countries need to articulate programs for overseas infrastructure development that adhere to certain standards of quality and transparency. The EU’s newly announced Global Gateway and the US Build Back Better World (B3W) initiative, for example, present similar yet uncoordinated visions for global infrastructure support. The OECD’s research capacity, its commitment to transparency and high-quality growth, and its broader membership beyond the G7 make it a good candidate as a hub to formulate standards for global infrastructure development.

- Common ground on climate policy: All countries accept the need for climate change mitigation strategies, but approaches vary widely, creating a need for coordination and policy interoperability. The OECD can be a platform to align economic instruments, from the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism to American electric vehicles procurement programs.

- Best practices for secure supply chains: Many countries are rethinking the risks of over-relying on one country—particularly adversarial ones—for critical supply chains. There is a need for countries with shared values to align tools to assess and mitigate supply chain concerns.

- Combating forced labor: The OECD has produced guidelines in the past meant to help firms and countries conduct adequate due diligence on forced labor in their supply chains. As the EU and the US work on regulatory instruments to combat these practices, the OECD can be a forum for aligning these policies in ways that address these issues while avoiding an excessive compliance burden on businesses.

- Economic coercion: Many countries, including Sweden, Canada, and Australia, have experienced economic coercion from China as a result of political tensions. Though the WTO has formal mechanisms to address certain acts of coercion, these processes are often too slow and not necessarily effective. The OECD could function as a group to compare responses, issue common statements of solidarity, and push back collectively.

Conclusions

The challenges posed by non-market economies require an organization like the OECD to step forward. This does not mean other groups don’t also have crucial roles to play or that more inclusive organizations are irrelevant. But for aligning approaches on advanced market economy concerns, the OECD is an excellent solution for gathering information, sharing best practices, and moving toward common guidelines.

Fashioning a shared market economy agenda will not be easy. There will be criticism that some issues (addressing subsidies, for instance) should be managed at bigger organizations like the WTO, and that moving the conversation will undermine existing multilateral institutions. Preserving multilateral governance is an important objective. But if the members of these organizations disagree over fundamental issues around the centrality of liberal economic governance, then these organizations’ limits must be acknowledged, too, and the discussion advanced within the next-most-inclusive body.

Boldness on certain issues has sometimes been quietly discouraged—at the OECD, as elsewhere—for fear of undermining relations with China. But a more serious advanced economy caucus is not bad news for China. If market economy debates remain fragmented, market countries are likely to lack the confidence to keep the doors open to even pedestrian commercial interaction with authoritarian nations. A more confident market cohort is more likely to be open to engagement. Beijing convenes the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and south-south summits to share perspectives and make plans germane to the developing world needs; market economies need to meet to discuss their issues as well.

Despite the challenges, there are no other international organizations with the research capabilities, track record of policy formulation, and right membership size to do the job. It will be far easier and more productive to resolve these issues under an existing organization like the OECD rather than to start from scratch. The timing for the OECD is good as well. Sixty years ago this September, the convention that transformed the Marshall Plan-era OEEC into the OECD of today came into force. On that date, market economies adopted an organization built for the needs of the immediate post-war recovery into a body to address the contemporary needs of economic growth. New challenges and new leadership could make 2021 another such turning point.

[1] A review by Ron Gass in the OECD Observer (No. 236, 2003) noted, “NATO and the OEEC were the two arms of a Western strategy to provide security and prosperity in the post-war period.”