China Pathfinder: Annual Scorecard 2022

China Pathfinder, a joint project of Rhodium Group and the Atlantic Council's GeoEconomics Center, compares China’s economic system to those of market economies

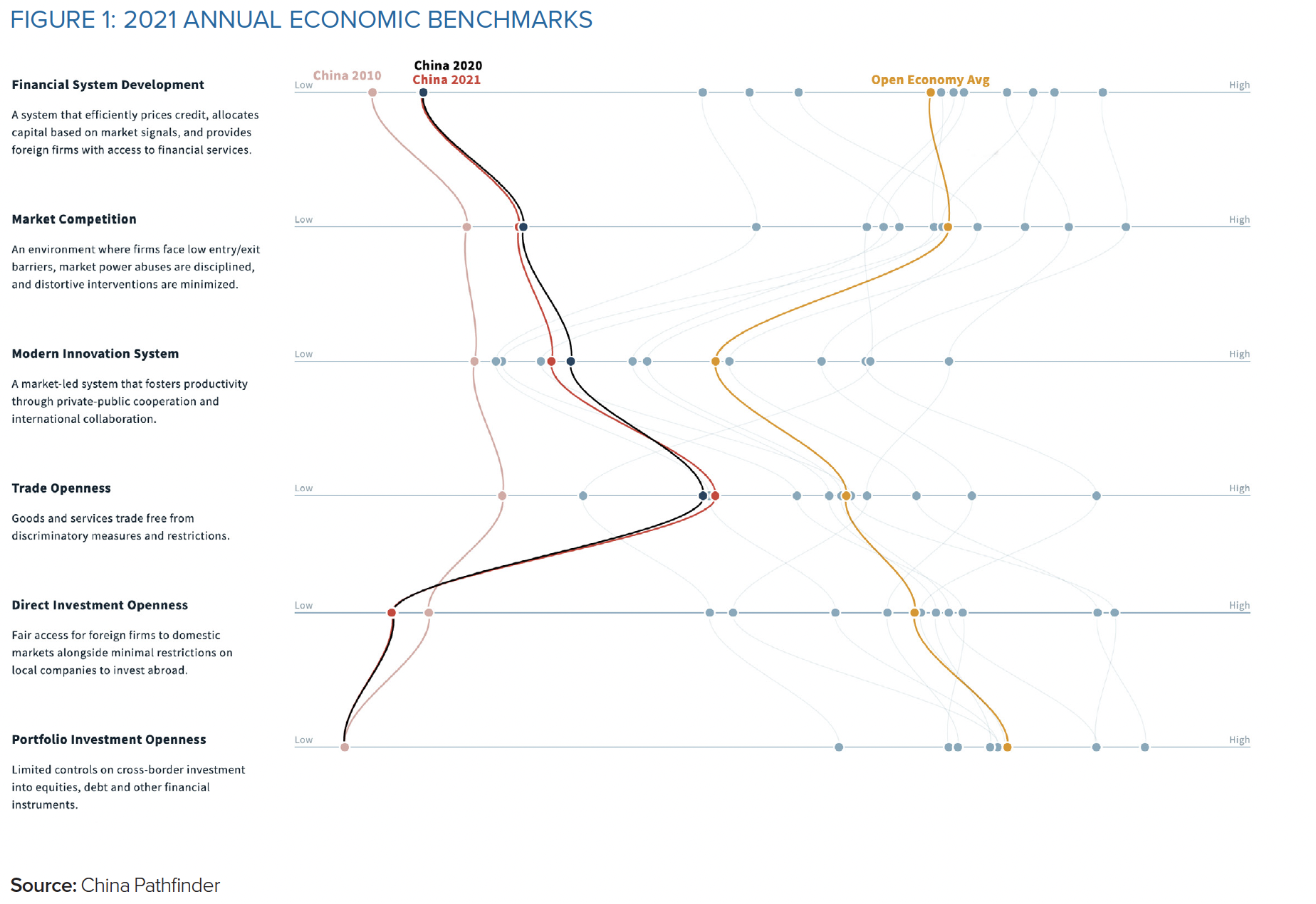

China Pathfinder, a joint project of Rhodium Group and the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center, compares China’s economic system to those of market economies. This juxtaposition is important at a time when questions are mounting about Beijing’s economic trajectory, and both policymakers and businesses around the world are assessing how to respond and position themselves. This report looks at six components of the market model: financial system development, competition, innovation system, trade openness, direct investment openness, and portfolio investment openness. Our annual scorecard situates China in relation to ten leading market economies to establish a data-centered benchmark for discussion and analysis. We supplement the annual report with quarterly updates that zero in on the most important policy developments in China. This approach is designed to encourage a more constructive discussion of policy shifts taking place in Beijing, from the recent crackdown on technology companies, to the “dual circulation” strategy, and debate over “common prosperity.”

Key Findings

China’s progress toward market economy norms slowed in most areas in 2021, though not enough to undermine the market opening efforts that took place since 2010. On our innovation system and trade metrics, China saw real progress in 2021 compared to its 2010 benchmarks, scoring higher than several OECD economies. In trade, China even improved on its 2020 performance. China’s financial system development, market competitiveness, and openness to investment, however, have stagnated; in these areas, the gap between China and market economies remains the largest. In upcoming reports, we hope to shed light on whether China’s economic performance is just temporarily reflecting the government’s aggressive steps to contain the COVID-19 pandemic, or if Beijing is diverging from market thinking in a more structural way.

Most of the OECD economies we track show a slight divergence from open market norms since 2010. For instance, Australia, Italy, and Spain saw some backsliding in their financial system development and market competitiveness, while German and South Korean markets saw a lapse in openness to foreign direct investment. Portfolio investment openness was the only bright spot, where all economies (except the UK) deepened portfolio markets or reduced cross-border restrictions compared to 2010. Intervention by governments in response to the pandemic played a role in the recent drift away from market openness. While most advanced economies are now moving on from the pandemic, ongoing geopolitical tensions in 2022, such as the war in Ukraine, could complicate their post-pandemic recovery.

In innovation, China had a higher composite score than Canada, Italy, and Spain. It also surpassed the open economy average in venture capital investment intensity. However, this progress comes with caveats. The role of the state in determining where innovation takes place—via government guidance funds and subsidies—and Beijing’s crackdown on technology companies risk undermining the innovation gains that China has made in recent years. Looking ahead, there is a risk that weakening foreign investment in China could chip away at the country’s innovative potential.

China’s composite score in trade comes closest to those of market economies, exceeding South Korea and Italy’s scores. But, here too, there are caveats. First, China’s remarkable competitiveness in goods trade is counteracted by its high barriers in digital services trade, where its score has declined in recent years. Second, non-tariff barriers cloud China’s trade landscape, benefiting domestic champions and hurting foreign players. Third, the US-China trade war continues to undermine confidence in deepening two-way trade for the long run. Thus, we saw China’s MFN tariff rate increase since 2020 (though it is still lower than it was in 2010), and while the US and the EU countries lowered their MFN rates, their tariffs on Chinese exports have not decreased. Finally, China’s economic growth continues to rely on exports; this is increasingly problematic given the domestic COVID-related disruptions and the relatively rapid recovery in China’s trading partners, which will drive a decline in demand for Chinese goods.

China’s investment openness has decreased since 2020, with a small slump in cross-border equity and bond volumes, as well as a drop-off in outbound FDI volumes. Though China’s restrictions on direct investment and portfolio investment have not changed, other factors such as the crackdown on technology firms and zero-COVID lockdowns have discouraged investment. As China’s scores in both areas of investment openness have been the furthest from market economy norms since 2010, the latest signs don’t do much to alter the dim picture.

President Xi Jinping will be confronted with important policy choices at the conclusion of the 20th Party Congress. Xi is widely expected to earn a third term as leader at the congress, freeing his hand to take bolder action in the face of formidable economic challenges. This could provide an opening for 2013-era market reform promises to reappear on the agenda. But while unfinished policy reform work is plain to see, few analysts in or outside of China can point to evidence of impending market reform acceleration.