China Pathfinder: Q1 2023 Update

An aggressive public campaign to allay concerns about the direction of China’s economy has not been underpinned by a convincing shift in policy.

China Pathfinder is a multiyear initiative from the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and Rhodium Group to measure China’s economic system relative to advanced market economies in six areas: financial system development, market competition, modern innovation system, trade openness, direct investment openness, and portfolio investment openness. To explore our data visualization and read our 2022 annual report, please visit the China Pathfinder site.

China reopened its borders in the first quarter of 2023 and rolled out the rhetorical welcome mat for foreign investors. This included pledges to promote foreign investment and imports, restoration of suspended long-term visas, and high-level visits by Chinese leaders abroad and foreign leaders in China. But an aggressive public campaign to allay concerns about the direction of China’s economy has not been underpinned by a convincing shift in policy. The restructuring plan that emerged from the “Two Sessions” meetings in March did not reassure the private sector, nor did it suggest that Beijing is poised to tackle the root causes of its macroeconomic malaise.

Meanwhile, pressure on foreign consultancies, due diligence providers, and others (including Bain & Company, Mintz Group, and Deloitte) further dampens business confidence. Heightened geopolitical tensions with the US also cloud the picture. Turning a cold shoulder to perceived American hostility, Beijing sought to warm relations with Europe: it had success with French President Macron, but faced setbacks at the European Commission, including a universally condemned comment by China’s ambassador to France that some European nations aren’t sovereign.

Quarterly Assessment and Outlook

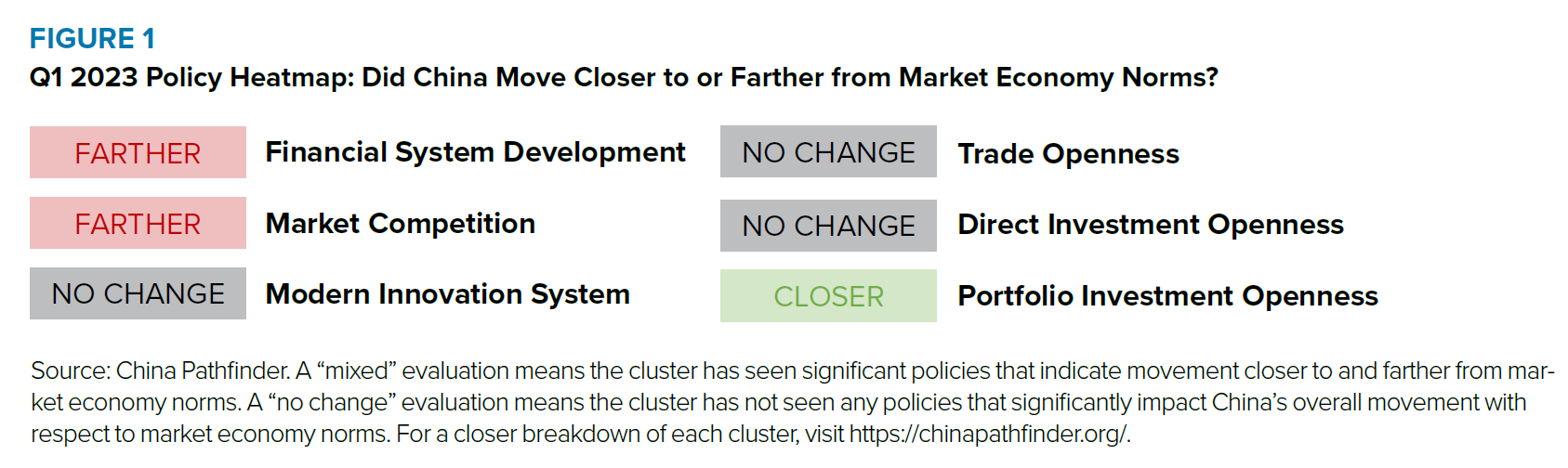

The Bottom Line: In the first quarter of 2023, Chinese authorities were active in three of the six economic clusters that make up the China Pathfinder analytical framework: financial system development, competition policy, and portfolio investment. There were fewer developments in the innovation, trade, and direct investment clusters. In assessing whether China’s economic system moved toward or away from market economy norms in Q1, our analysis shows a negative picture.

A Look at Q1 Trendlines

China’s government hoped to put the economy on a firm recovery path by abandoning the zero-COVID measures in the last days of 2022. Months later, it is clear that 2023 will look better than 2022. Service sector activity, consumption, and even sales in the stricken property sector show positive momentum. Exports, the primary driver of China’s economy during the pandemic years, are reported to have been robust, though not to G7 markets, and with some inconsistent data. There are other reasons for concern. The pandemic years did lasting damage to income growth, employment, and business confidence. Exports are likely to weaken significantly over the course of the year as external demand flattens, and long-term structural problems continue to drag down growth. Domestically, local governments face financial pressures—from declining property sales, the hangover from COVID-era expenditures, and difficulties refinancing debt—that will require a near-term response from Beijing.

The external dimension is important too. The US October 7, 2022 controls on the export of advanced semiconductor technologies and the expected outbound investment screening regime could make it more difficult for Beijing to sustain economic growth. In a March survey conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce in China, 66 percent of member companies—and a higher proportion of technology companies—named uncertainty in US-China relations as their top business challenge in the country. China’s foreign direct investment in 2023 may also take a hit: over half of surveyed US companies do not plan to make new investments in China this year.

Financial System

Policy decisions taken in the first quarter highlighted the government’s conflicting approach to securing financial stability. On the one hand, Beijing pledged to alleviate the fiscal stress of local government and restructuring debt. On the other hand, it is launching a campaign-style crackdown on the financial system, which will result in the Party having a larger role in the allocation of credit, which runs counter to financial reform. Without a more compelling solution to financial system risks, the outlook for longer-term growth will remain dim.

Xi Jinping directly addressed the local government debt problem at last December’s Central Economic Work Conference (CEWC), saying: “We will increase the disposal of existing implicit debt, improve the debt maturity structure and lower interest payment burdens.” Translated into plain speak, this means debt maturities will be extended, locking away financial institutions’ funds with local governments for longer periods of time. The burdens on financial institutions will be amplified when local governments are allowed to repay loans at a lower interest rate. In other words, these measures will likely impair financial institutions, which have no clear way to absorb these costs. This suggests that Beijing expects the financial system to answer to Party priorities in the future rather than profit incentives.

Beijing’s measures are a mix of carrots and sticks designed to increase financial system depth and openness, while simultaneously tightening political oversight. On the positive side of the ledger, the central government is making it easier for localities to list their state-owned enterprises (SOEs) on the stock market, which often represent their most valuable assets, where sales can assist in the repayment of local debt. In Q1, the most important effort to achieve this was the rollout of a new registration-based system for initial public offerings (IPOs), which replaced a system that required approval from the securities regulator. Some hard requirements on profitability and other financial ratios have been relaxed under the new IPO system, making it easier for SOEs to qualify for listings.

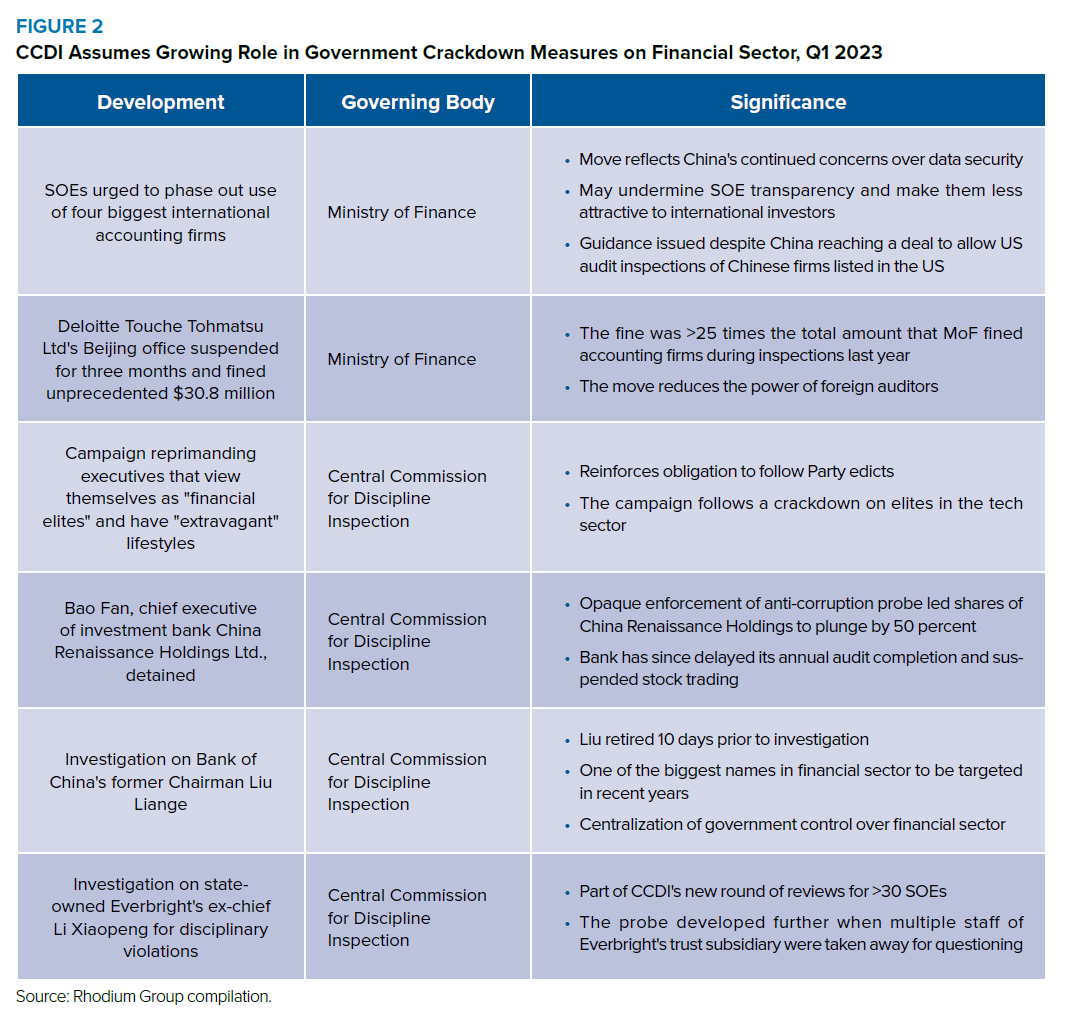

At the same time, the Chinese government has increased its scrutiny of the financial sector, with the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) launching numerous anti-corruption investigations targeting financial executives (Figure 2). Both the former chairman of the Bank of China, Liu Liange, and the former chief of the financial conglomerate Everbright Group, Li Xiaopeng, were investigated for “serious disciplinary violations.” Meanwhile, the case of financier Bao Fan demonstrated the lack of transparency around the government’s anti-corruption campaign; Bao disappeared for nearly 10 days before his company reported that he was cooperating with authorities in an investigation. While these practices are not new, developments in Q1 2023 suggested that the government is intensifying its campaign. Zhou Chengyue, a former Ministry of Finance official and Chairman of the China Public-Private Partnership Fund, is the latest prominent name in the financial sector to be investigated by the CCDI.

Market Competition

Beijing’s crackdown against tech companies appears to be entering a new phase in 2023. In a move that reassured some investors, Didi Global received the green light to accept new user registrations. Alibaba also seems to have gotten over the hump, as it announced a split into six separate units that will each explore IPO options. However, government scrutiny of the data security policies of private companies and of sectors that do not align with Party goals is increasing.

Starting in June, companies will face greater scrutiny when it comes to cross-border flows of personal data, as the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) published the final version of the Cross-border Transfer of Personal Information Standard Contract measures in March. This Standard Contract is one of three mechanisms governing data transfers in China. Compared to the June 2022 draft, the final measures are stricter regarding how closely cross-border data transfer agreements must align with the Standard Contract, the requirement for foreign recipients of personal information to be monitored by Chinese authorities, and how the total volume of personal information transferred is calculated.

Meanwhile, foreign companies are watching carefully for the fallout from the recent raid by Chinese authorities of US due diligence firm Mintz Group, which saw several staff detained. The raid, which took place just days ahead of the China Development Forum, was a departure from the reassurances for foreign companies the forum was meant to foster. Official scrutiny on foreign firms continued into Q2, with Chinese police questioning employees of the US consulting firm Bain & Company at their Shanghai office. These developments raise concerns about fair treatment of foreign businesses and their ability to access data for assessing risks in Chinese firms and the broader market landscape.

In the first quarter, local companies were not immune to new limitations imposed selectively by the government. The China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) began to use a traffic light system to select which local firms would be allowed to list on China’s main stock exchanges, according to the industry they belong to. Sectors such as COVID-19 testing (once a government priority) and the food and beverage industry were given a “red light.” This system allows the government to directly determine the success of certain sectors over others; as state priorities change, companies are incentivized to anticipate the next government-favored sector or activity rather than focus on delivering profits.

Portfolio Investment Openness

As part of its effort to boost economic growth in 2023, Beijing has rolled out several measures that marginally increase the country’s openness to portfolio investment. For instance, the stock exchanges of Shenzhen and London signed an agreement to move forward in establishing the Shenzhen-London Connect, which will improve the connectivity of capital markets. The CSRC also encouraged overseas listings by explicitly stating that it would support the offshore listing of Chinese companies with variable interest entity (VIE) structures if they are compliant with national security-related regulations. This is a softening of the previous guidance, where regulators had warned companies against using VIE structures to list abroad. Finally, China’s new registration-based IPO system will not only have positive effects on the financial system but will also allow investors to invest in a wider range of companies. These developments suggest that China is taking steps to open up its capital markets in hopes of boosting foreign investors’ confidence in the Chinese market.

Special Topic: Bureaucratic Restructuring is a Solution in Search of a Problem

At the 2023 Two Sessions, the government released a major restructuring plan, involving the establishment of new departments, consolidation of responsibilities, and an overhaul of the financial system. While the extensive nature of this restructuring may suggest the government is focused on maximizing efficiency in the economy to boost growth, the reality is more complex and less positive. Rather than implementing policies that address systemic problems in the country’s economy—such as the fragile property sector, the loss of consumer and business confidence following destabilizing zero-COVID measures and unpredictable government intervention in different sectors, and high levels of local government debt—the restructuring plan overall does not enhance transparency or indicate that the Party is willing to offer more room for the market to define outcomes.

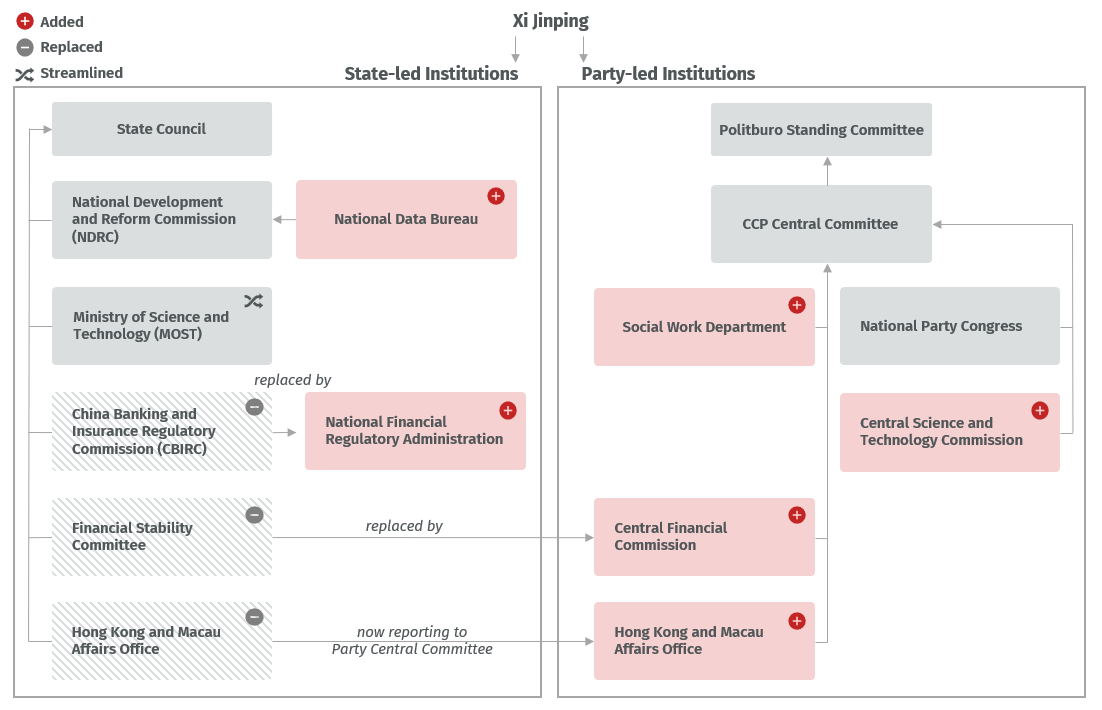

The restructuring plan shifted control over certain bureaus from the State Council to the Party’s Central Committee (Figure 3). Premier Li Qiang’s speech at the first meeting of the new State Council in March similarly suggested that the State Council’s role is to implement Party decisions. As traditional barriers between the Chinese state and the Communist Party melt away, the influence of markets in driving outcomes will weaken. While bureaucratic restructuring may improve governance and reduce inefficiencies, it is not a panacea for the challenges facing China’s economy.

Financial Restructuring

The shift in oversight of the sale of corporate bonds from the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), which has been a bottleneck for bond issuance, to the China Securities Regulatory Commission is a minor streamlining step that could increase financial system openness. However, this will depend on how the change in responsibility is managed.

On the downside, other bureaucratic restructuring measures signal an increase in Party control over the financial system. The bureaucratic overhaul involved the creation of a new financial regulator, the National Financial Regulatory Administration (NFRA), to replace the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC). NFRA will have significantly more power, with the centralization removing several levers of local government control of credit allocation at city levels and below. The revamp also resurrected the Party-directed Central Financial Commission, replacing the financial stability committee previously controlled by the State Council. In combination with the Party’s establishment of a department for “social work” or building Party committees within private enterprises, the efficiency of China’s financial system seems to be moving in the wrong direction.

Data Security

The financial sector was not the only area affected by the restructuring plan: the Chinese government founded the National Data Bureau “in an effort to balance supervision with encouragement of the digital economy.” This could streamline supervision over private companies that have access to data that the government deems sensitive. As the Party-led CAC has been the primary regulator of the tech industry, this new bureau could balance CAC’s focus on national security with new measures focused on treating data as an economic resource. Details on the extent of the National Data Bureau’s authority have not yet been released, so the potential effects on China’s market competition atmosphere remain unclear. Even though there is increased clarity on how the data regulation process will unfold, the types of data flows that will be restricted are still ill-defined. This gives the government ample latitude in determining the companies and activities that would be subject to mandatory disclosure or security reviews.

The creation of the data bureau comes at a time when tighter data security is being prioritized. For instance, the academic database China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), a frequently used resource for non-China based researchers that provides a library of Chinese government documents, academic papers, and datasets, notified foreign universities that it will be limiting their access effective April 1, 2023. The CAC also announced that it will conduct a cybersecurity review of US memory chip company Micron, with the stated goals of eliminating national security risks and ensuring supply chain security of critical information infrastructure. Though data regulations are necessary in rapidly growing technology spaces, the Chinese government’s tightened control of academic sources corresponds with worsening relations with the United States, where a clear lens studying China’s domestic economy from the outside in is more useful than ever. In the semiconductor space, Beijing’s actions come in response to US-led restrictions on exports of advanced chip manufacturing equipment to China.

Companies were further alarmed in Q2 when the NPC updated China’s anti-espionage law, broadening the definition of espionage—currently limited to state secrets—to include transfers of information pertaining to national security and interests. So far, the government has not clarified what would be considered “national security and interests,” and the widespread applications of this revised legislation are a cause for concern.

Innovation

At a time when the United States and other countries are introducing new measures to restrict China’s access to core technologies such as semiconductors, Beijing’s restructuring plan centered around developing self-reliance in science and technology. The Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) was elevated to a policymaking role in coordinating China’s research and development. Going forward, MOST will have an increased say on science-related funding and allocation. The reorganization could have a streamlining effect, as specific project planning and implementation would be handled by other ministries. The overlap in goals and disorganized efforts to meet targets across ministries and provinces could be less severe with the revised system. The area of innovation is yet another where the Party is eager to have more direct control. A Party committee for S&T, the Central Science and Technology Commission, was created and consolidates the work conducted by various leading groups. This demonstrates that Xi and the CCP will drive the direction of China’s innovation in the foreseeable future. The bureaucratic streamlining may not have its intended effect: increased CCP oversight could in fact limit the range of R&D activities that businesses pursue.

Looking Ahead

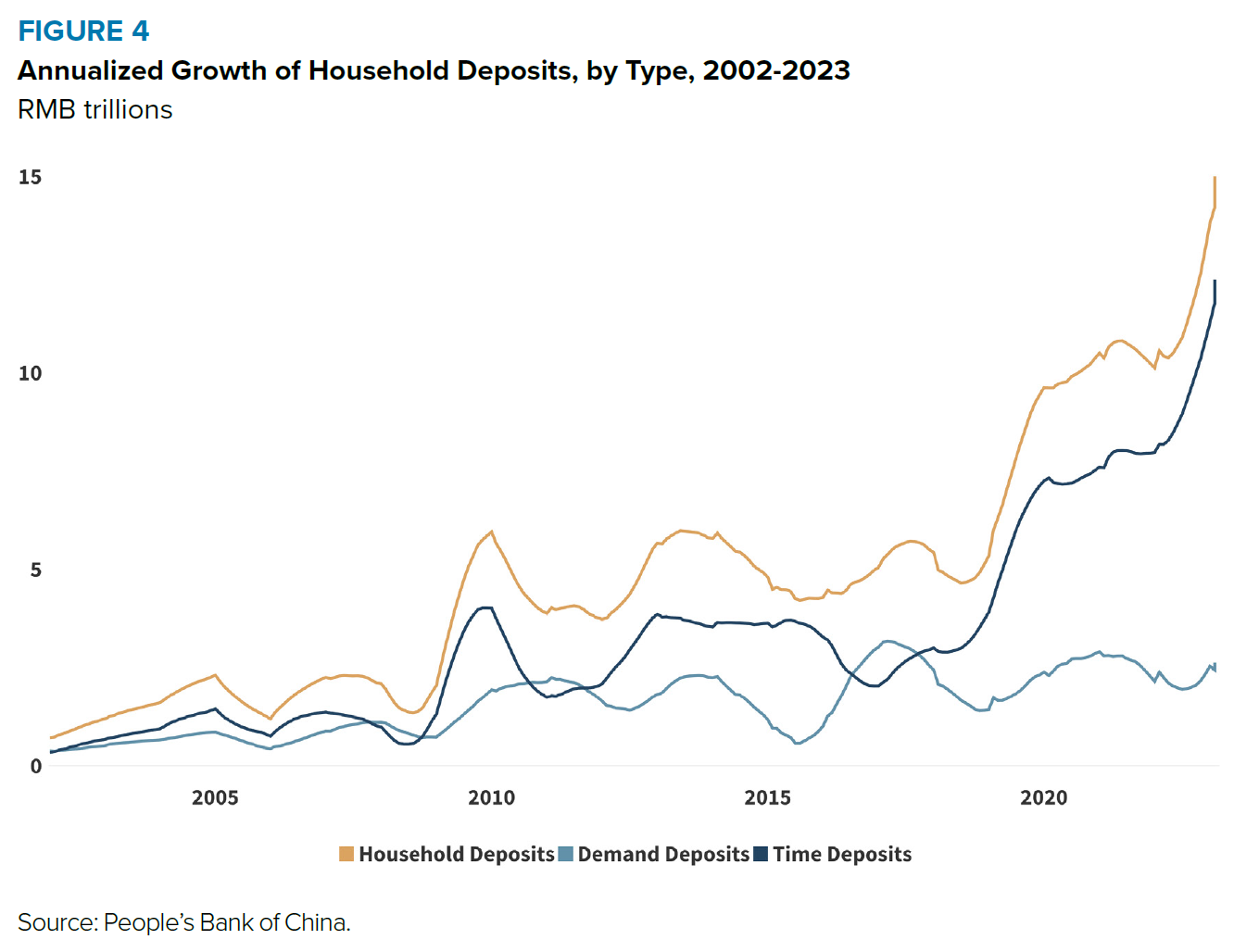

Last year, we said that one of the most important challenges that Beijing faced was restoring the confidence of domestic consumers and foreign investors. Developments in Q1, however, fell short of providing reasons for optimism on this front. Consumption growth, when adjusting for positive effects of the National Bureau of Statistics’ data revisions, saw only a weak rebound despite the easing of COVID-19 restrictions, and Beijing did not offer direct fiscal support for incomes. Though consumer spending and travel have surged for the May 1 Labor Day holiday in China, household savings rates have risen sharply in 2023 as a whole. And because much of these savings are in the form of time (rather than demand) deposits, they suggest that any robust rise in consumer spending is still far off.

Surveys of US and EU businesses point to growing trepidation about investing in China given the worsening business environment. While some companies, including BlackRock and Fidelity, have expanded their operations in China, others like the Van Eck Associates Corp. disbanded its China mutual fund group. Similarly, the future of Vanguard’s joint venture with Ant Group remains unclear amid news reports of a planned exit from the Chinese market. Still, most foreign companies are taking a wait-and-see approach, looking for concrete signs that the government is serious about delivering on its promises of more opening.

External factors are also playing an important role in shaping investor perceptions toward China. US-China relations took a turn for the worse in Q1 2023, following the shooting down of a Chinese surveillance balloon over the United States, a chummy meeting between Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow, and growing tensions over Taiwan. While some had held out hope of an easing of tensions after a meeting between Biden and Xi at the G20 summit last year, communication channels between Washington and Beijing have instead shut down almost completely, and the path to restoring dialogue is uncertain. The US is expected to continue to ramp up its restrictions on technology engagement with China in the months ahead, including the introduction of an outbound investment screening mechanism in May. While Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen appeared to offer an olive branch to Beijing, by stressing in a speech in mid-April that the US was keen for dialogue and had no intention of containing, isolating, or pursuing a far-reaching economic decoupling from China, she also made clear that Washington would continue to prioritize national security in its relations with Beijing.

In Europe, we have seen contradictory signals on China. In a hawkish speech in late March, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said that China has turned the page on a reform and opening of its economy, and entered a new era of security and control. She urged Europe to reduce its economic dependence on China and explore tighter restrictions on the transfer of technologies as part of a new “de-risking” strategy. A visit days later from French President Emmanuel Macron, however, sent a different signal, drawing criticism from other European capitals. Macron brought a large business delegation with him to Beijing and presided over the signing of numerous deals, distancing France from the United States and pledging to work closely with Beijing going forward. Germany’s foreign minister Baerbock stuck a different tone after her latest trip to China, stating that Beijing is increasingly becoming a “systemic rival.”

Still, the Yellen and von der Leyen speeches suggest a path forward for transatlantic cooperation on China. The coming months will be crucial in this regard, with a G7 summit looming in mid-May, a meeting of the US-EU Trade and Technology Council taking place at the end of May, and an important meeting of European leaders in Brussels a month later, where von der Leyen will try to build support for a new economic security strategy. We will be watching for signs of whether Beijing can succeed in driving a bigger wedge between Europe and the United States, including by offering European businesses carrots, while hitting US firms with sticks. Against this increasingly murky backdrop, policymakers will need objective benchmarks to assess whether China is delivering on its reform and opening promises, or pursuing a tactical, selective approach which continues to raise doubts about its future as a business location.

See our other China Pathfinder research

The authors wish to acknowledge the members of the China Pathfinder Advisory Council: Steven Denning, Gary Rieschel, and Jack Wadsworth, whose partnership has made this project possible. Niels Graham, Jeremy Mark, and Miles Munkacy were the principal contributors from the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center.