China Pathfinder: Q2 2022 Update

China’s economic growth slowed to 0.4 percent year-on-year in the second quarter of 2022, despite aggressive steps by authorities to support struggling companies, boost consumption, and address the spike in youth unemployment

China Pathfinder is a multi-year initiative from the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and Rhodium Group to measure China’s system relative to advanced market economies in six areas: financial system development, market competition, modern innovation system, trade openness, direct investment openness, and portfolio investment openness. To explore our inaugural data visualization and read our annual report and updates, please visit the China Pathfinder site.

China’s economic growth slowed to 0.4 percent year-on-year in the second quarter of 2022, despite aggressive steps by authorities to support struggling companies, boost consumption, and address the spike in youth unemployment. These measures amounted to short-term firefighting. There were few signs of the fundamental structural reforms needed to put the Chinese economy on a sustainable long-term growth path. Beijing’s aversion to relinquishing economic control to market actors has laid the groundwork for more financial instability in the second half of 2022, including in the struggling property sector. With the 20th Party Congress looming, we see little chance of a change in approach, even if the Chinese economy veers toward a hard landing. Some analysts point to episodic Q2 endorsements of market reform and the end of “campaign style” regulation as evidence of correction. Until more definitive policy reversals are evident, however, the outlook for liberal policy reform in China to address deep-seated structural flaws in the economy remains dim.

Quarterly Assessment and Outlook

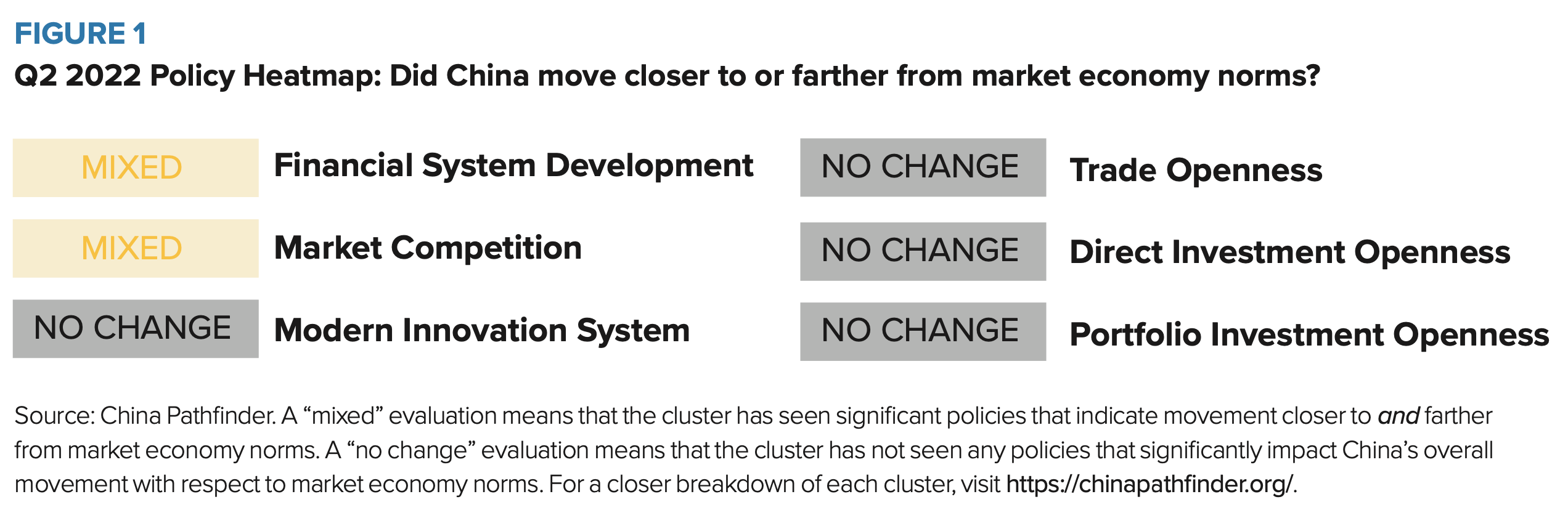

The Bottom Line: In the second quarter of 2022, Chinese authorities were active in two of the six economic clusters that make up the China Pathfinder analytical framework: financial system development and competition policy. There were fewer developments in the innovation, trade, direct investment, and portfolio investment clusters. In assessing whether China’s economic system moved toward or away from market economy norms in this quarter, our analysis shows a mixed picture.

Figure 1 reflects the direction of China’s policy activity in the domestic financial system, market competition, and innovation system, as well as policies that impact trade, direct investment, and portfolio investment openness. This heatmap is derived from in-house policy tracking that weighs and evaluates the impact of Chinese policies in Q2. Actions are evaluated based on their systemic importance to China’s development path toward or away from market economy norms. The assessment of a policy’s importance incorporates top-level political signaling with regard to the government’s priorities, the authority of the issuing and implementing bodies in the Chinese government hierarchy, and the impact of the policy on China’s economy.

A Look at Q2 Trendlines

Policy activity in Q2 2022 was dominated by measures to offset economic slowing caused by COVID-19 lockdowns and an ailing property sector. The State Council rolled out “33 Measures” to stabilize the economy, most of them temporary steps to support businesses. This “all hands on deck” support showed that, despite bullish official messaging, the economy is not doing fine and is unlikely to come close to meeting the targets China’s leaders have set for it. While some of the measures introduced in Q2 could boost small- and medium-sized enterprises, most amounted to subsidies that undermine, rather than promote, reform. In June, the State Council announced an increased credit line of RMB 800 billion for policy banks to fund infrastructure projects. This was followed by the announcement of another RMB 300 billion in financial bonds for infrastructure projects, innovation, and local bond-funded projects. In addition, China is reportedly negotiating with auto manufacturers about extending electric vehicle (EV) subsidies that are due to expire this year. All of this underscores how shaky China’s commitment to market reform is, when confronted with risks to the economy.

Financial System

The Chinese government took small steps to liberalize the financial sector, while retaining its “common prosperity” drive. On the positive side of the ledger, the National People’s Congress passed the Futures and Derivatives Law (FDL), the first comprehensive attempt to bring a legal framework to this growing market. The law took effect on August 1. China’s derivatives market has suffered several high-profile setbacks in recent years. The first was the $10 billion short squeeze on nickel giant Tsingshan Holding Group in Q1 2022. The second was the crash of a Bank of China wealth management product linked to global crude oil futures contracts in 2020, which generated significant losses for over 60,000 individual investors. As a result, the Chinese government has pushed for further improvements in the oversight of derivatives markets. Besides protecting investors and preventing market manipulation, the FDL legally recognizes practices like close-out netting (whereby a company’s contractual obligations to a defaulting counterparty are terminated), bringing China more in line with international norms.

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) upgraded its toolkit for guiding bank deposit rates, a change quietly introduced in early 2022. The idea is to price deposits in line with market interest rates, such as government bond yields and the loan prime rate, rather than setting them using PBOC benchmark rates. This can help lower lending rates for corporates and shore up credit demand within the flagging economy. The move is a meaningful step toward interest rate liberalization. In addition, the State Council and the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) introduced a private pension scheme that would allow individuals to invest their pensions in certain stable financial products. This scheme would diversify investment options for Chinese households and offer more medium-term opportunities for growth in household incomes and private consumption.

On the other side of the ledger, Chinese regulators sought to place limits on salaries in the financial sector, inserting themselves into internal business decision making. In May, the Securities Association of China issued guidance warning the industry to avoid handing out “excessive” short-term incentives to employees and said doing so would result in compliance risks. A month later, the Asset Management Association of China published a regulation on performance assessment and compensation in asset management companies, which stated that at least 40 percent of bonus payments to senior staff should be deferred for three or more years. Media outlets, including the Financial Times and Bloomberg, reported that in mid-June the CSRC officials held meetings in which they asked foreign investment banks to reveal the salary details of top executives and urged pay curbs, though the CSRC later denied the reports. This campaign should be seen in the context of the Party’s “common prosperity” drive, in which regulators have used vague guidance or targeted crackdowns to compel companies and banks to prioritize their “social responsibility.” For foreign companies in China, this is a new sign of government intrusion in business operations.

Market Competition

The Central Committee of the CCP and State Council released opinions on building a “unified national market,” part of a broad push to centralize the fragmented domestic market. The document targets local protectionism and market segmentation. While previous policies focused heavily on reducing entry and exit barriers, the latest top-level guidance expands the scope to factors of production and covers areas such as intellectual property rights and regulatory standards.

While combating protectionism may lead to more market-based outcomes, the push for a “unified national market” could also result in a centralization of authority, leading to market-distorting outcomes. Importantly, the centralization effort includes unifying the social credit system—which ranks citizens and companies based on their behavior and trustworthiness—and “integrating social and financial credit information” for commercial entities. It is unclear how far this push will go and the extent to which it will affect individuals as well as companies. It seems likely, however, to further consolidate the central government’s control over Chinese citizens’ data, giving local officials more latitude to target specific firms and punish entities that run afoul of the CCP’s ideological red lines. In sum, these developments could help or hinder marketization depending on how they are applied.

Continuing a years-long mission to improve standard-setting and centralization, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPCSC) passed amendments to the foundational Anti-Monopoly Law (AML), which will increase oversight of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and introduce prohibitions on the use of data, algorithms, technology, capital advantages or platform rules to engage in monopolistic behaviors.

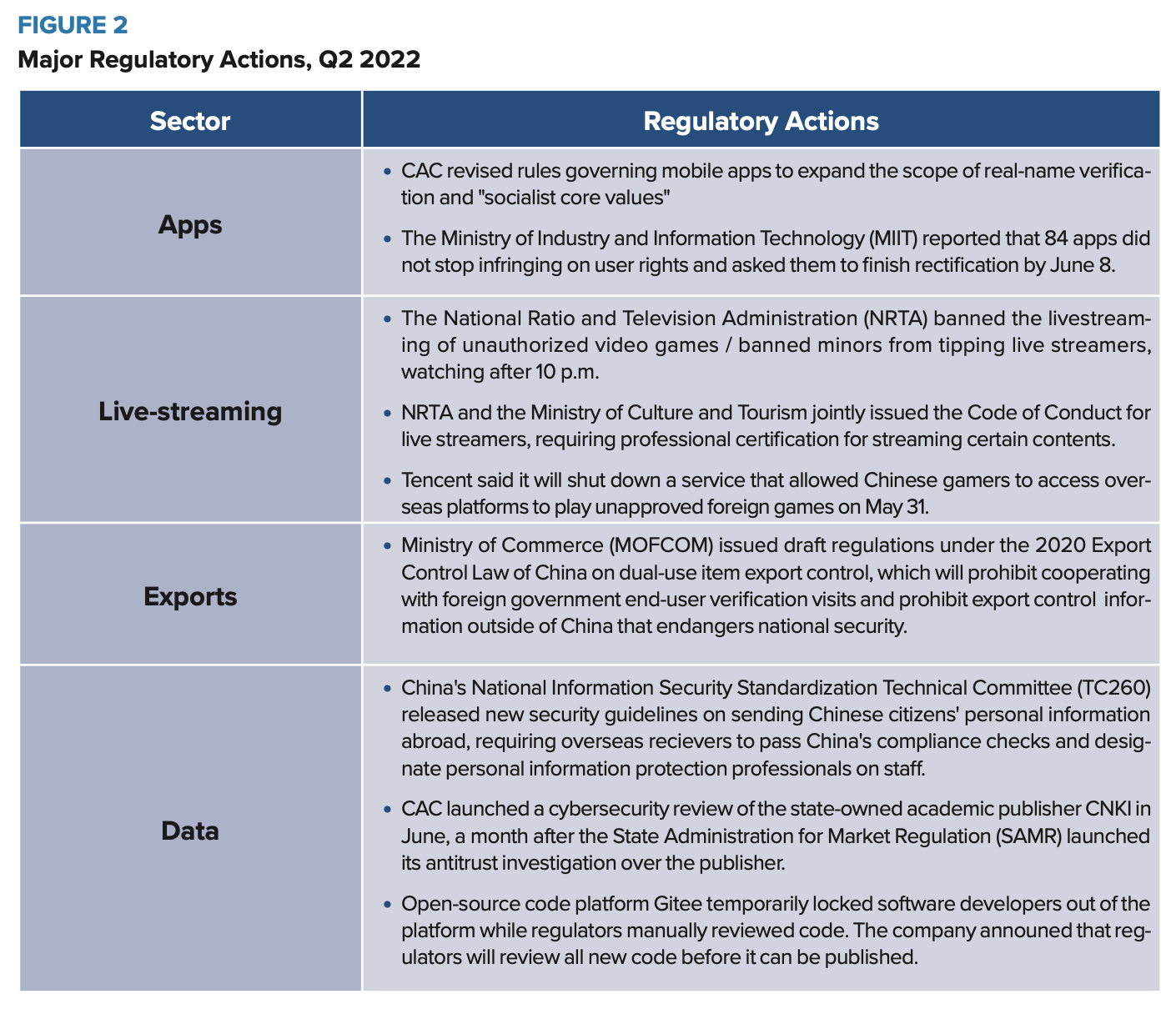

The tech crackdown has shifted focus, but platforms are still in the crosshairs of China’s regulators. During a CCP meeting in April, President Xi reiterated the need to regulate the “disorderly expansion of capital,” on the grounds that capital has a profit-seeking nature and can harm economic and social development if not regulated and restrained. It appears that China’s digital platforms should be bracing for further government intervention. In Q2, regulators turned their attention to controls on apps, the use of data by citizens, and gaming (Figure 2).

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) finalized rules on cross-border data transfers, which go into effect September 1. Companies that transfer personal, important, and other sensitive data overseas may be subject to security assessment. Many outstanding questions remain, including what constitutes a data export or “important data.” For foreign companies in China, compliance risks may rise as CAC kicks off enforcement.

CAC also announced a formal campaign to rein in internet giants’ algorithm abuses—an important indicator that the campaign against tech companies is entering a new phase rather than ending. The regulator said that this effort will include on-site inspections of firms and reviews of various services provided by platforms. While the campaign further develops standards for algorithm use, it also gives the government broad license to continue tightening its grip on information platforms. These latest regulatory measures reiterated the importance of upholding “socialist core values” in the online space, making it harder for platforms to balance market-based goals with adhering to regulators’ ideological guidance.

Special Topic: China’s Unemployment Problem

Ensuring stability in employment acquired a new urgency in 2022. Absorbing a record 10.7 million new university graduates into the labor market was always going to be challenging during the pandemic, but in Q2 the shrinking economy and zero-COVID lockdowns in major Chinese cities pushed unemployment to new highs. In April, the urban unemployment rate reached 6.1 percent, the highest since the early days of the pandemic in March 2020. The unemployment rate for those aged 16-24 grew even faster, from 15.4 percent a year ago to 19.3 percent in June. This was the highest rate recorded by the National Bureau of Statistics since it started publishing the data in 2018. Unemployment data are politically sensitive in China, so official reporting likely understates the severity of the problem.

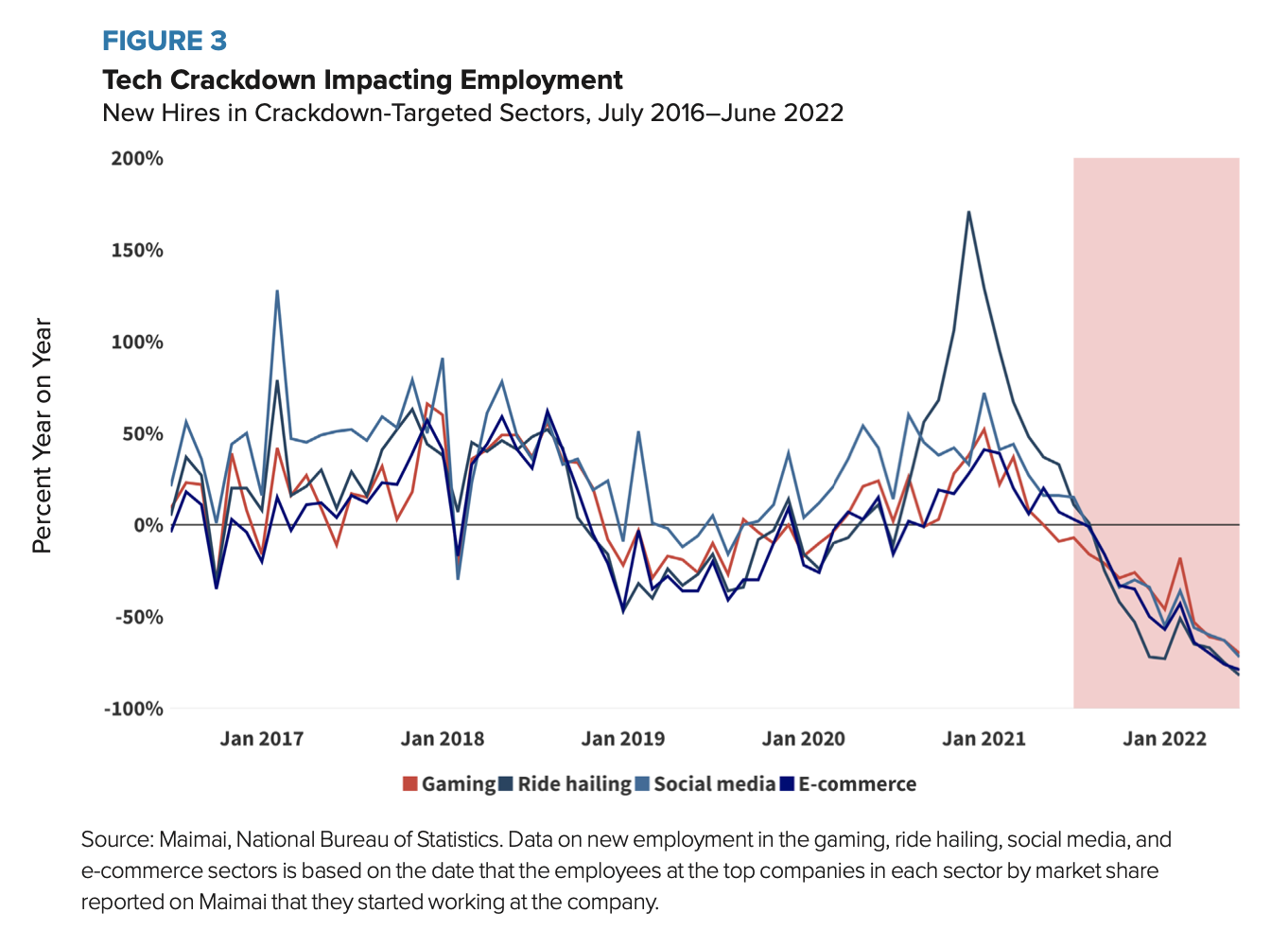

Hiring shrinks, firing swells. The ongoing regulatory campaign that shut down China’s private education industry last summer has impacted hiring in many sectors. Employment data from Maimai, a job networking platform, showed the steep decline in new hiring in sectors (gaming, ride-hailing, social media, and e-commerce) targeted by the crackdown that began in July 2021 continued in Q2 2022 (Figure 3). In these sectors, Q2 hiring fell 65 -75 percent from one year ago. The slowdown was steepest in June, with new hiring down 82 percent at top ride-hailing platforms and 79 percent at top e-commerce and food delivery platforms.

The private sector is becoming less desirable for new graduates. With zero-COVID policies and regulatory crackdowns shaking public and investor confidence, private firms have become riskier places to seek employment. Large tech firms including Alibaba, Tencent, and JD.com have announced heavy layoffs, in some cases up to 15 percent of their workforces. Meanwhile interest in government jobs has soared: in 2022, over 2 million applicants took civil service exams, a new record and a 28 percent increase over 2018. Though the public sector generally offers lower pay than the private sector, it is seen to offer lifetime security (an “iron rice bowl” in old Chinese parlance). This perception endures even as civil servants in some provinces have seen their annual incomes cut 20-30 percent this year.

Falling salary expectations are reflected in the data. Zhaopin, a Chinese recruitment firm, reported that expected salaries have dropped 6.2 percent this year compared to 2021. In 2020 and 2021, university graduates saw only a 4 percent increase in starting salaries, as opposed to a 7 percent increase for 2018 and 2019 graduates. Concerns over employment prospects, economic stability, and income are weighing on consumer sentiment. A PBOC survey in Q2 found that more than 58 percent of respondents planned to prioritize saving over consuming, compared to 54.7 percent in the previous quarter. Computer science majors are having an especially difficult time finding employment due to the tech crackdown. Graduates with a degree in Marxism, on the other hand, have seen their fortunes lifted in the current political environment. Demand for graduates with Marxism degrees has risen 20 percent over the past year, with some places offering quadruple the average salary and a signing bonus to attract that talent. As President Xi prepares for a third term, he and CCP leadership are rewarding alignment with Party ideology in both the education system and the private sector.

The Party is concerned about youth unemployment, but there are no easy solutions. Millions of young Chinese talk of “lying flat,” a metaphor for doing nothing (or opting out of the rat race) at a time when the job market is highly competitive and pressures to succeed are on the rise. Premier Li Keqiang called the current employment situation “complex and grave” as his government struggles to stabilize job markets with tax and fee breaks designed to encourage companies to hire or defer layoffs. But unemployment insurance premium rebates or discounted utility prices cannot make up for the effect of shrinking profits on hiring. More job fairs and graduate recruitment platforms will not solve China’s employment problems.

Acknowledging that the private sector cannot create the millions of new jobs China needs on its own, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) urged SOEs to expand recruitment efforts. Authorities are also assuming the role of career planners. In June, four ministries issued a document encouraging college graduates to work and start businesses in rural communities. In return, the government is offering tax breaks, special entrepreneurship subsidies and loans.

It is not the first time the government has directed its most educated citizens to work in undeveloped rural areas and poorer regions for the purpose of alleviating the urban labor surplus. As early as 2003 and 2005, the State Council piloted programs encouraging college graduates to become grassroots government officials or to support economic development in the western regions. Young Chinese have been reluctant to follow the government’s call due to a massive urban-rural income gap. Research from 2017 shows that 100,000 village officials in China hold an advanced degree (only about 17 percent of all village officials), and more than 80 percent of graduates who leave urban centers for the countryside are doing so because they were born there.

Looking Ahead

The outlook on China’s growth beyond the first half of 2022 depends on a careful reading of government intent and how it is likely to respond to realities on the ground. The feeble growth in gross domestic product (GDP) is emblematic of an economy weighed down by Beijing’s policy missteps. The unrelenting crisis in China’s property sector means it will remain a drag on the economy in the second half of the year, even if COVID restrictions ease and activity in other sectors improves. The banking protests that rocked Henan province and the rising incidence of people walking away from their mortgages—trends that have dominated the headlines in July—point to a deep structural malaise that will require decisive action to reverse.

Some analysts believe the severe economic headwinds China is encountering will force changes in policymaking. As Q3 2022 got underway, some leaders were talking more openly about the downturn and the challenges it will bring. Speaking to foreign business leaders at the World Economic Forum, Premier Li Keqiang said arduous efforts would be needed just to maintain stability in growth rates. The GDP growth target of 5.5 percent for 2022 that Beijing stuck with through the first half of 2022 now seems likely to be shelved, with early reports that leadership has instructed government officials to view 5.5 percent growth as “guidance” instead of a firm target. Voices urging respect for entrepreneurs and an end to “campaign style” regulations are becoming more frequent. Think tank economists are being given more latitude to talk about policy adjustments with foreign counterparts.

These signs point to a revision of official priorities in favor of reform, but it is not clear yet whether a meaningful shift will materialize. Policy messaging remains muddled. There are signs that zero-COVID policies may be softening, though not enough to cheer markets. At its Q2 meeting, the Politburo, China’s top decision-making body, made clear that “political calculations” were paramount in tackling the pandemic and warned against relaxing efforts to stamp out the virus—despite the economic costs. The challenges of steering China back to a market course are gargantuan, but they may be less insurmountable than telling millions of Chinese citizens that low growth is the most they can hope for.