China Pathfinder: Q3 2021 Update

This quarterly China Pathfinder update is part of a multiyear initiative from the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and Rhodium Group to measure China’s system relative to advanced market economies.

In the third quarter of 2021, a Chinese economy already straining under COVID- 19 was rocked by energy shortages, while Evergrande, the country’s largest real estate developer, inched toward a full-blown debt crisis. At the same time, the government broadened the ongoing crackdown on technology giants, delivering another hit to investor sentiment. These disruptions are not the result of policies launched this quarter; rather, they reflect the consequences of the government’s failure to introduce much-needed market discipline, including in the real estate and energy sectors. Framing the outlook on China’s economic health is a broader uncertainty surrounding the future of the country’s development path under the slogan of “common prosperity” championed by Xi Jinping. Beijing’s moves in response to the challenges this quarter prioritized political objectives over market-oriented policy reform—not an encouraging signal.

China Pathfinder is a multiyear initiative from the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and Rhodium Group to measure China’s system relative to advanced market economies in six areas: financial system development, market competition, modern innovation system, trade openness, direct investment openness, and portfolio investment openness. To explore our inaugural data visualization and read our 2021 annual report, please visit the China Pathfinder website.

Quarterly Assessment and Outlook

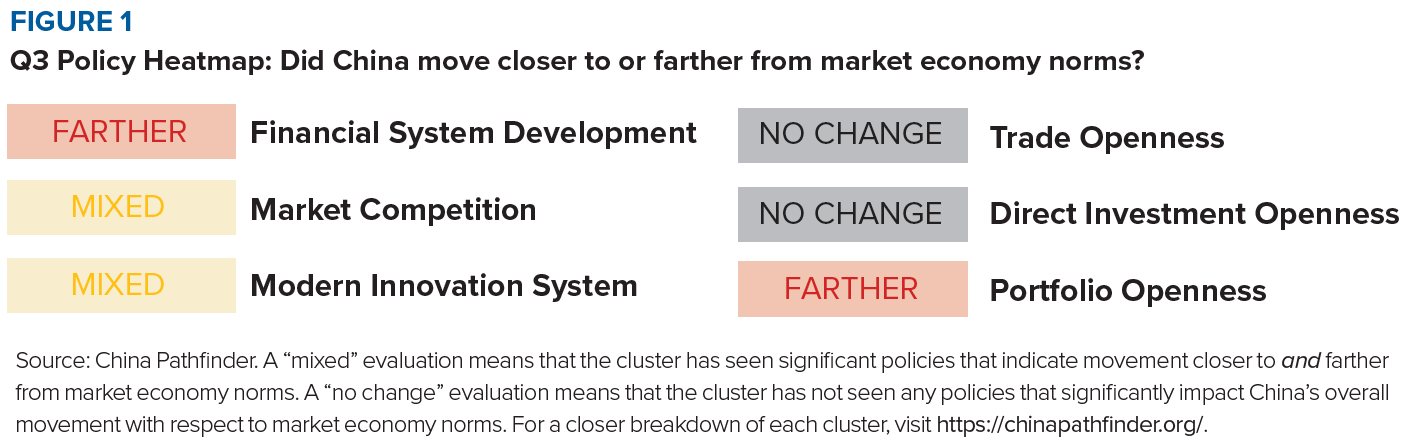

The Bottom Line: In Q3 2021, Chinese authorities were active in four of six economic clusters that make up the China Pathfinder analytical framework—financial system development, competition policy, innovation, and portfolio investment openness—with fewer developments in the trade and direct investment openness clusters. In assessing whether China’s economic system moved toward or away from market economy norms in this quarter, our analysis shows a mixed-to-negative trendline.

Figure 1 reflects the direction of China’s policy activity in the domestic financial system, market competition, and innovation system, as well as policies that impact trade, direct investment, and portfolio investment openness. This heatmap is derived from in-house policy tracking that weighs and evaluates the impact of Chinese policies in Q3. Actions are evaluated based on their systemic importance to China’s development path toward or away from market economy norms. The assessment of a policy’s importance incorporates top-level political signaling with regard to the government’s priorities, the authority of the issuing and implementing bodies in the Chinese government hierarchy, and the impact of the policy on China’s economy.

A Look at Q3 Trendlines

The defining feature of the Chinese government’s policymaking in the third quarter was the strengthening of state direction in the private sector. This was ostensibly motivated by concern about domestic demographic decline, and the need to alleviate household financial burdens to promote social confidence. The nascent “common prosperity” campaign emphasized reducing inequality and upholding social stability. Xi Jinping has described common prosperity as an essential requirement of socialism and a key feature of Chinese-style modernization, making it the watch- word for the government’s high-level messaging. The impact of the campaign remains to be seen, however, with no blueprints made public on how it is to be implemented.

Authorities unveiled minor policies related to the financial system, but the ongoing Evergrande debt crisis was the main event. The most significant policy signal was a non-signal: the absence of a clear decision on what concrete action to take to resolve Evergrande’s situation and stem contagion in the property sector. This nonintervention could be read generously as pro-market if the government clearly communicated its intent to inject self-discipline into markets and let Evergrande face the consequences. However, officials underestimated the severity of contagion and systemic concern, made confusing pledges to prevent a full reckoning, and ultimately claimed that the initial policy disciplines that precipitated the property stress had been misinterpreted. If the government intended to build confidence in the direction of financial reform, the outcome has been the exact opposite.

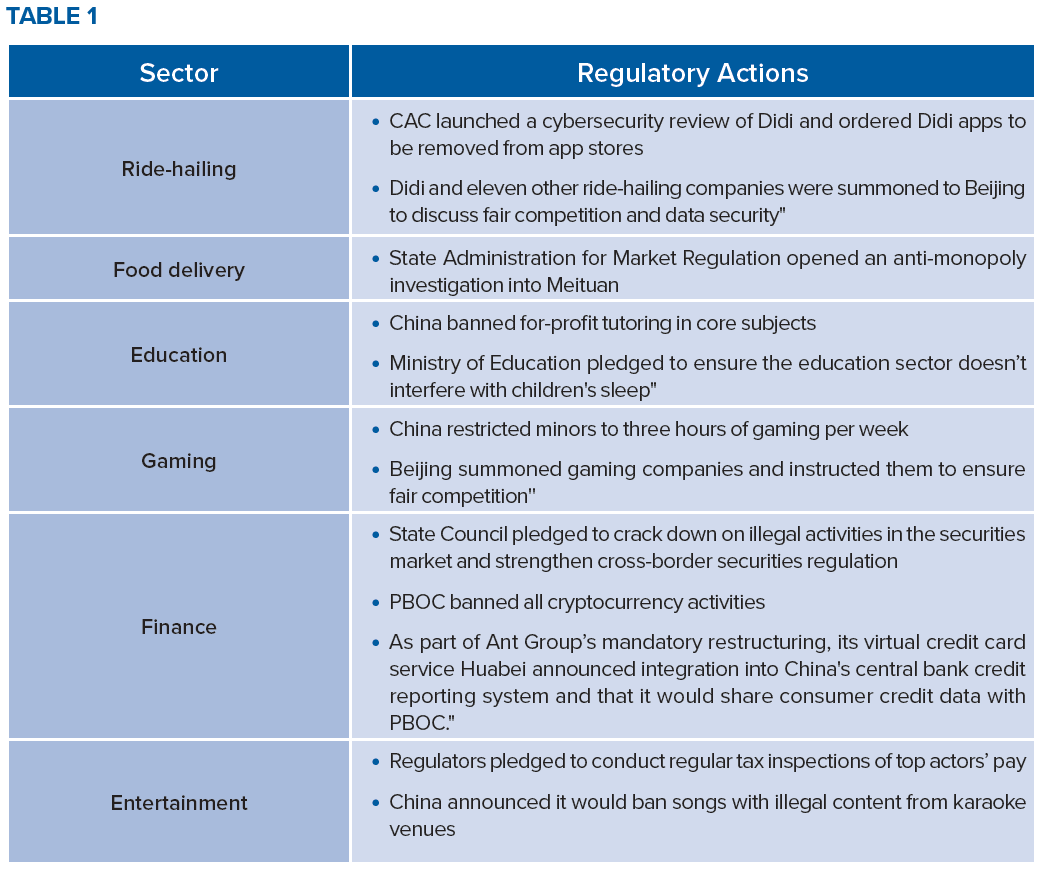

Developments in China’s market competition environment were mixed. Several new regulatory actions (Table 1) are meant to address legitimate market regulatory issues, while others are harder to distinguish from heavy-handed government interference. These include banning the private education sector from operating on a for-profit basis—something that was permitted, encouraged, and invested in for decades.

Beijing has explained its crackdown on leading Internet-based businesses as having several aims. Tech companies were labeled as engaging in monopolistic practices and abusing worker rights, generating the need for urgent regulatory enforcement. Other concerns centered on how companies collect, utilize, and share data—issues which reflect the state’s insistence on con- trolling data. Last year, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CCCPC) and State Council designated data a “factor of production,” alongside land, labor, capital, and technology, underscoring its importance in their vision of economic development. The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC)—an agency responsible for cyberspace security and Internet content regulation—emerged as the key enforcer of the government’s new activist posture in China’s tech sector. After launching a cybersecurity review of Didi two days after its initial public offering (IPO) in the United States, CAC issued a draft revision to the Cybersecurity Review Measures, which would mandate a cybersecurity review for most overseas IPOs.

In the tech crackdown, Beijing is pursuing political goals with seeming disregard for economic costs. This contrasts with a long-standing track record of Beijing hedging political aims to protect growth. The rollout of regulations on the private sector during Q3 triggered a sell-off that shaved $1.5 trillion or more from technology stocks. The primary targets of Beijing’s ire have been Internet service-sector businesses, while advanced manufacturing came in for praise. Strategic goals such as self-sufficiency in semi- conductors are understandable (if hard to realize), but state planning, interference in consumer choices, and micromanaging patriotism in the private sector are not likely to promote technological independence.

The government expanded its role in the innovation system with the rollout of three key policies: the “Outline for Establishing China as an Intellectual Property Rights Superpower (2021-2035),” issued by the State Council; draft regulations on algorithms released by CAC; and the Personal Information Protection Law passed by the National People’s Congress (NPC). These policies paint a mixed picture. On the one hand, Chinese consumers’ personal data would be better protected, and there are new pledges to improve the intellectual property regime for domestic and foreign firms. On the other hand, state actions to restrict how companies use data (especially cross-border flows) cast a pall on the data-driven knowledge economy.

Government’s intrusion into market activity is weighing on the outlook for portfolio investment. The Cybersecurity Review Measures would make it harder for Chinese companies to go public on foreign exchanges. The China Securities Regulatory Commission’s proposed checks on Chinese companies that use the popular variable interest entity (VIE) legal structure to list over- seas have chilled capital raising. (VIEs are extensively used by tech companies such as Alibaba to go abroad.) Officials announced the establishment of a new Beijing Stock Exchange, China’s third major exchange after the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges, with the aim of serving smaller private companies. This signals intent to support this hard-pressed segment of the economy, but it will take considerable time to see whether it makes a dent in small business financing challenges.

Special Topic: Evergrande

In a quarter where the Chinese government was active on many fronts, this China Pathfinder update focuses on the Evergrande crisis, which has major implications for the development of China’s financial system, while also highlighting broader systemic risks in China’s economy.

Evergrande crisis and the structural problems in China’s system: The economic turmoil surrounding Evergrande has become a litmus test for how the Chinese government will balance financial stability against market discipline. Evergrande has accumulated over $300 billion in liabilities—compounding years of risky financial practice and a massive expansion of leverage in China’s economy, particularly in the property sector. Historically, China’s real estate sector has expanded unchecked as the government prioritized economic growth and households sought property as a secure store of value. Meanwhile, local governments, which are responsible for upward of 85 percent of expenditure but receive only about 60 percent of tax revenue, filled the subsequent short- fall by selling land. As a result, debt ballooned even as linkages between property developers and local governments created a persistent moral hazard, with investors assuming the government would step in to bail out any troubled companies. Last year, how- ever, the Chinese government introduced caps for debt ratios dubbed the “three red lines” to target property developers’ debt growth and to dramatically reduce land purchases from local governments. Thus far, the government has not intervened to resolve the Evergrande debt crisis, even as other property developers began to default on onshore and offshore bonds.

China’s systemic debt problem has left only undesirable policy options: A Chinese government intervention to bail out Evergrande would signal a major watering down of the “three red lines,” with negative consequences for China’s market discipline. The failure to act, however, could result in a long-term chilling effect on China’s economic growth as property sales and construction activity continue to weaken, even though the Chinese government has claimed that the risks from Evergrande are “controllable.” Beijing has few good options, underscoring its failure to foster a robust, well-regulated financial system that can manage the repercussions of even large firms exiting the market. As we noted in our 2020 China Pathfinder annual scorecard, China still lags far behind market economies in terms of allocating credit to the financial system in an efficient way, and lending is controlled heavily by the government. We point to extreme corporate indebtedness over the past decade as primary evidence of these issues.

China’s policy decisions will have a tangible impact on the Chinese consumer and economy at large: As China’s real estate market contributes to roughly 20 percent to 25 percent of the country’s gross domestic product, Beijing’s approach to Evergrande and other large property developers has major implications for the entire economy’s future growth trajectory. Evergrande alone owes money to hundreds of contractors, suppliers, and local governments across China, which means its failure would affect broad swaths of China’s economy.

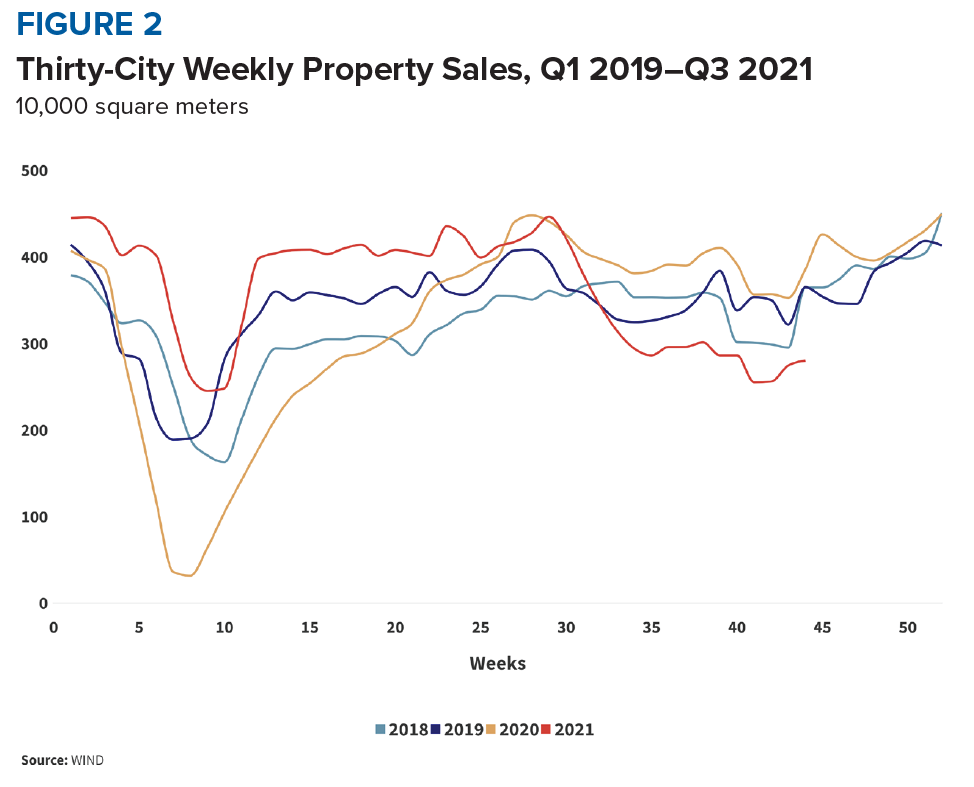

The outcome of the Evergrande crisis directly impacts home buyers: Those who have already purchased apartments and are paying mortgages risk being stranded as construction stalls, while prospective home buyers could be deterred from investing in real estate due to falling prices and fears that developers will fail to complete construction. Figure 2 illustrates the latter phenomenon, with a severe drop in weekly property sales across thirty Chinese cities since July 2021. As contagion spreads throughout the property sector and property values fall, real estate owners will see a major hit to their household wealth, which in turn would weigh on their spending. In the absence of other investment alternatives, real estate comprises around two-thirds of Chinese households’ assets. In other words, the Evergrande fallout could further scupper the Chinese government’s ambition to transition the economy to a consumer-dependent growth model. In the long run, this would impact regional and global markets as Chinese demand for foreign goods wanes.

Looking Forward

Relative to our annual China Pathfinder benchmarking report published this October, Beijing policy outcomes this past quarter did not promote convergence with open-market norms. Our heatmap of quarterly developments shows negative or at best mixed signals of convergence. An emphasis on state intervention and deemphasis of marketization persist. In the acute phase of COVID-19, one could argue that heightened state intervention was called for by the pandemic, but this argument becomes less credible with time. Today’s positive signals—such as Vice Premier Liu He saying that “China will persist in opening up the economy”—are damage control on equally recent missteps, not compelling signs. The most convincing move would simply be acknowledgment that the current model is flawed, not that “China’s path is the right and correct one,” as President Xi declared.

Quarter-over-quarter annualized growth was barely above 2 percent this period—unheard of for China outside rare times of crisis. The growth rate will likely rise thanks to laxer property constraints, but that solution just circles back to the debt problem that property tightening was meant to fix. The shortcomings evident in the present policy mix are changing the China conversation, with risks to future growth potential the focal point. This is unfortunate because major decisions about strategy toward China, including in terms of whether economic “decoupling” is called for, are underway. Better signals of market reform from the Chinese government would have been especially helpful right now to damp down the most hawkish recommendations. China’s economic downturn will not stay inside its borders, and it is unclear how much Beijing will revert to “reform and opening” to get back on a potential growth track. Everyone from developing country commodities exporters to developed country portfolio managers has a stake in whether China manages to do so.

The inaugural edition of the China Pathfinder Quarterly Policy Tracker tests various approaches to the challenge of gauging policy directions. Based on this experience, we will augment and refine our approach in the quarters to come.