China Pathfinder: Q4 2021 Update

This quarterly China Pathfinder update is part of a multiyear initiative from the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and Rhodium Group to measure China’s system relative to advanced market economies.

China Pathfinder is a multiyear initiative from the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and Rhodium Group to measure China’s system relative to advanced market economies in six areas: financial system development, market competition, modern innovation system, trade openness, direct investment openness, and portfolio investment openness. Below please find our update for the fourth quarter of 2021. To explore our inaugural data visualization and read our 2021 annual report, please visit the China Pathfinder website.

In the fourth quarter of 2021, China moved farther from market economy norms. The real estate sector continued to dominate the headlines as Evergrande, the country’s largest property developer, finally defaulted, along with peers Kaisa, Sinic Holdings, Fantasia, and Modern Land. Meanwhile, the government’s regulatory crackdown intensified, culminating in ride-hailing giant Didi’s forced delisting from the New York Stock Exchange. The move may herald a broader unwinding of foreign listings, particularly for data-heavy Chinese companies. While VC flows to China’s tech startups showed recovery from a low in 2020, the main targets for this investment were hardware technology sectors favored by Beijing. With expectations for a slowdown in 2022 mounting, China’s leaders dropped their fiscal restraint and promised new stimulus at their year-end Central Economic Work Conference (CEWC).

Quarterly Assessment and Outlook

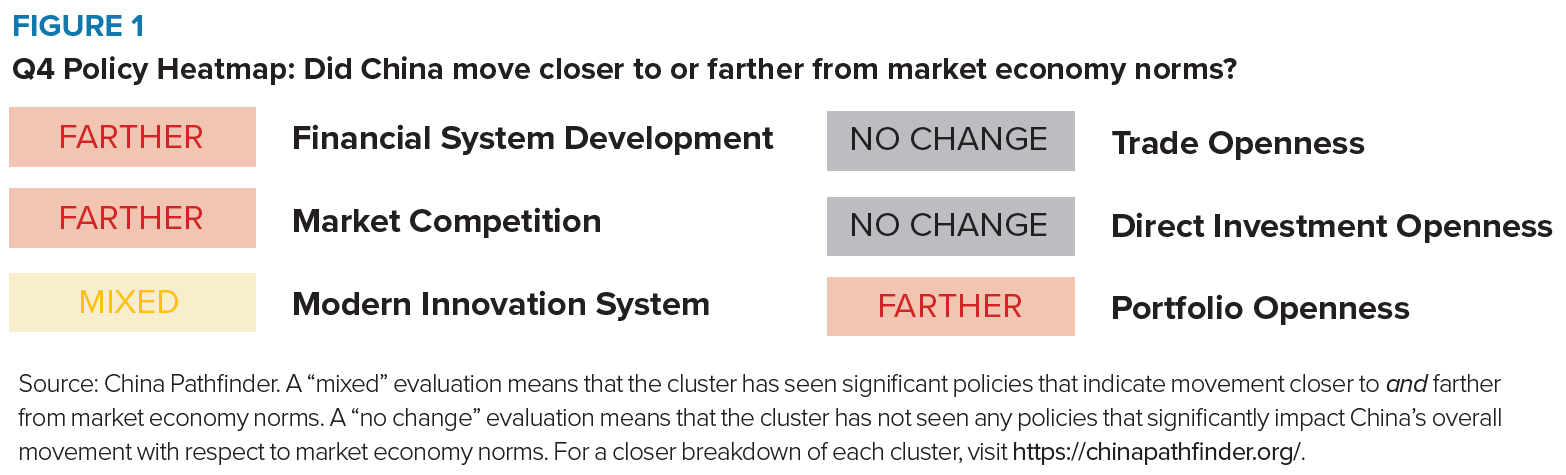

The Bottom Line: In Q4 2021, Chinese authorities were active in four of the six economic clusters that make up the China Pathfinder analytical framework: financial system development, competition policy, innovation, and portfolio investment openness. There were fewer developments in the direct investment and trade clusters. In assessing whether China’s economic system moved toward or away from market economy norms in this quarter, our analysis shows a primarily negative shift.

Figure 1 reflects the direction of China’s policy activity in the domestic financial system, market competition, and innovation system, as well as policies that impact trade, direct investment, and portfolio investment openness. This heatmap is derived from in-house policy tracking that weighs and evaluates the impact of Chinese policies in Q4. Actions are evaluated based on their systemic importance to China’s development path toward or away from market economy norms. The assessment of a policy’s importance incorporates top-level political signaling with regard to the government’s priorities, the authority of the issuing and implementing bodies in the Chinese government hierarchy, and the impact of the policy on China’s economy.

A Look at Q4 Trendlines

State intervention to shape market outcomes was the defining feature of policymaking in Q4 2021, reflecting a systemic shift, rather than just a COVID emergency phenomenon. At the Sixth Plenum in November, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) said the country had entered a “new era” under Xi Jinping, re-emphasizing the CCP’s leading role in steering long-term strategy. For the private sector, which spent 2021 adjusting to sudden shifts in policy priorities, toeing the Party line is becoming a necessity. This is particularly true for companies operating in the digital economy, as enforcement of “data security,” the government’s long-standing focus, kicked into high gear.

Financial System

The Chinese government rolled out few concrete policies related to the financial system, but de facto developments showed a Beijing poised to play a greater role in regulating financial markets in 2022 than in 2021. As the debt crisis in China’s property sector continued to metastasize from Evergrande to other developers in Q3, the Chinese government did not step in to stem the contagion, adding stress to the financial system. In Q4, it was Fitch, a US credit rating agency, that finally declared Evergrande and Kaisa in default, while the Chinese government continued to stay silent. The list of developers downgraded to default or near-default ballooned from three in Q3 to eight in Q4.

Without a new engine of growth, the slowdown in property sales and construction will be difficult to reverse. At a Politburo meeting in early December, messaging hinted at easing measures to “meet the reasonable housing needs of buyers.” At the CEWC, which took place days later, China’s government reaffirmed that it would support the property market. In 2020, the government introduced caps for debt ratios dubbed the “three red lines” to target property developers’ debt growth. While Beijing has not explicitly backtracked on the three red lines, it’s clear that China’s authorities are not prepared to let market forces alone shape a long-overdue shakeout in the property sector.

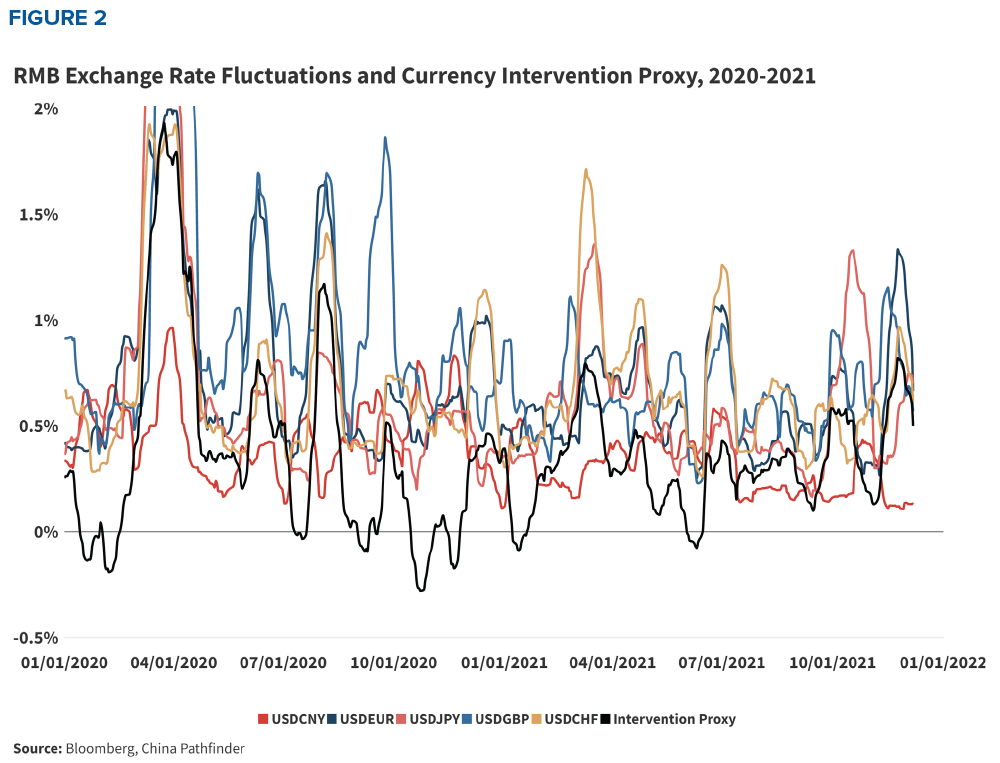

In Q4, China continued to intervene to limit currency fluctuations, reducing the scope for foreign exchange rate shifts to correct trade imbalances. When the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) intervenes to prevent an appreciation of the currency, it is effectively subsidizing exports and undermining market mechanisms. Throughout the past year, the central bank used a number of techniques to reduce its declared accumulation of foreign reserves on the PBOC’s balance sheet, including concealing reserves through Chinese commercial banks’ foreign currency holdings, or listing some of these holdings as “other foreign assets.” Beijing also attempted to limit currency appreciation by increasing banks’ foreign exchange required reserve ratio, rather than permitting more flexibility. All of these measures, captured via the proxy in Figure 2, are at odds with a market-driven approach to managing the exchange rate.

The CCP has also strengthened political oversight of China’s financial regulators and institutions. China’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) announced a two-month inspection designed to “strengthen the Party’s overall leadership in financial work…and promote comprehensive and strict governance in the financial field.” These inspections suggest a lack of trust in the ability of technocrats charged with regulating China’s financial system to carry out the Party’s political objectives. The CCDI investigators’ scrutiny of ties between financial institutions and private companies may also prompt banks to reduce lending to smaller companies in favor of less efficient, but more politically relevant, state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

Market Competition

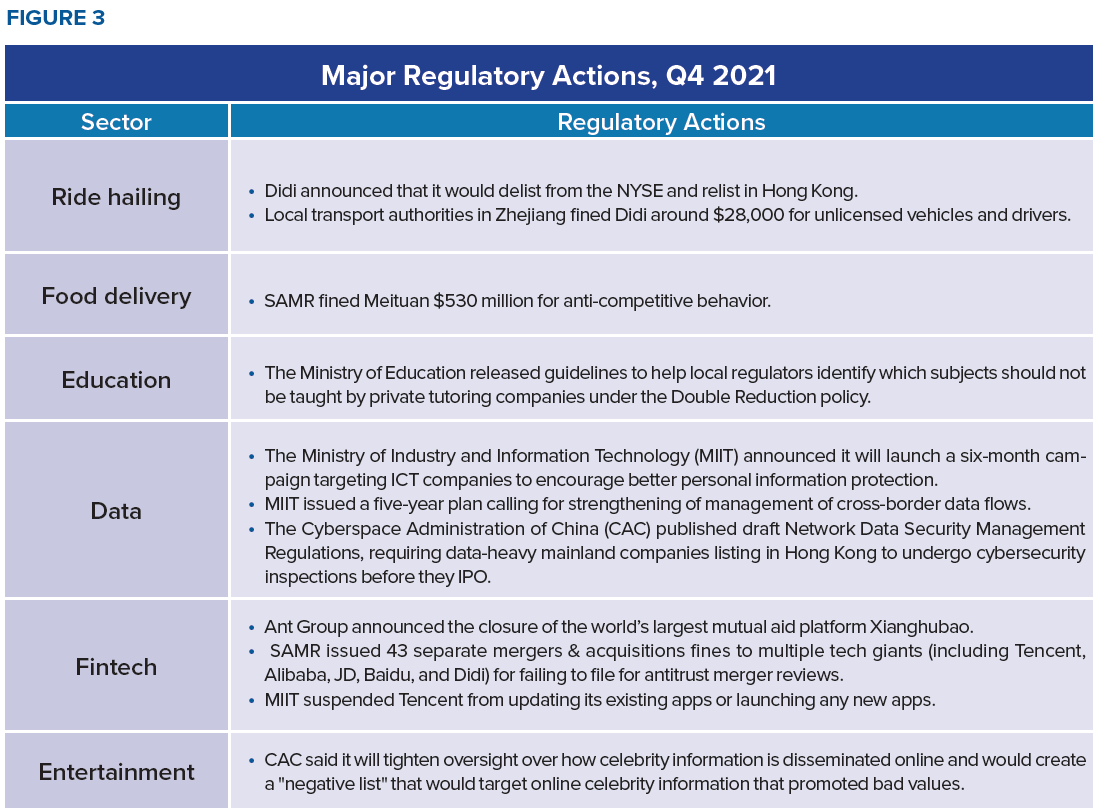

Developments in China’s market-competition environment also trended negative, driven by the government’s tightening grip on access to data and companies that operate in data-heavy sectors (Figure 3).

The government strengthened protections for consumer data from abuses by businesses, but not from itself. The draft Network Data Security Management Regulations, published in November 2021, classify data into three groupings accompanied by increasing safeguarding measures: general, important, and core. The definition of core data has not changed since the Data Security Law was passed last June, but the regulations further describe “important” data. This expansive category includes data on technologies and industries ranging from telecoms and financial services to artificial intelligence, as well as a catch-all class of data that may impact China’s political system, economy, and culture. While the regulations limit the access that private corporations have to consumer data, the classification system increases the state’s role in determining data rules and access. Absent clear delineation, most data held by China’s large companies could easily fall into one of the covered categories.

Under these data regulations, foreign companies operating in China face growing compliance risks. Because companies are prohibited from sharing data stored on the mainland with foreign government agencies such as law enforcement, abiding by both Chinese and foreign jurisdictions may become untenable. Meanwhile, the Shanghai Data Exchange opened for business about a week after the draft data security regulations were released—the latest in a series of moves by China’s government to boost its digital sector. Private companies previously showed hesitation in trading data on the other dozen-plus exchange platforms established across China over the past few years, with concerns that authorities may tack on regulations that transform businesses’ data into government property. The rise of local government-backed data exchange platforms and the government’s draft regulations to rein in companies’ possession of data notably do not limit the Chinese government’s own access to data.

China’s Anti-Monopoly Law could become a tool for the CCP to pursue industrial priorities. In October 2021, the draft amendment to the Anti-Monopoly Law (AML) was submitted to the National People’s Congress Standing Committee for review. The amendment specifically targets the digital economy, increases penalties on individuals and businesses that violate the AML, and provides the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) with more authority in conducting merger reviews. Though the AML has the potential to curb problematic practices of Chinese Internet giants, it also provides the Chinese government with increasing leeway to selectively regulate sectors according to CCP-established goals and favored industries.

In the last quarter, Beijing ratcheted up its campaign to punish Lithuania for allowing Taiwan to open a representative office in the country. European and US companies have reported that their exports are not being allowed into China by customs officials because they contain Lithuanian inputs. There are also reports that companies are being pressured to drop Lithuanian inputs from their supply chains. Though Beijing has used punitive economic tools against European Union (EU) countries in the past, the steps taken against Lithuania represent a serious escalation in its use of economic coercion. If they persist, these measures risk doing further damage to increasingly tense EU-China relations. This marks the first instance in which China has blocked imports from companies that are not based in the country they are targeting. In this case, having operations in, or working with suppliers from, Lithuania appears sufficient cause to face retribution. For foreign companies, the dispute highlights the risks of a further politicization of market access in China, an issue that is already a long-standing sore point. This campaign’s timing was particularly awkward—just as China was celebrating the 20th anniversary of its accession to the World Trade Organization.

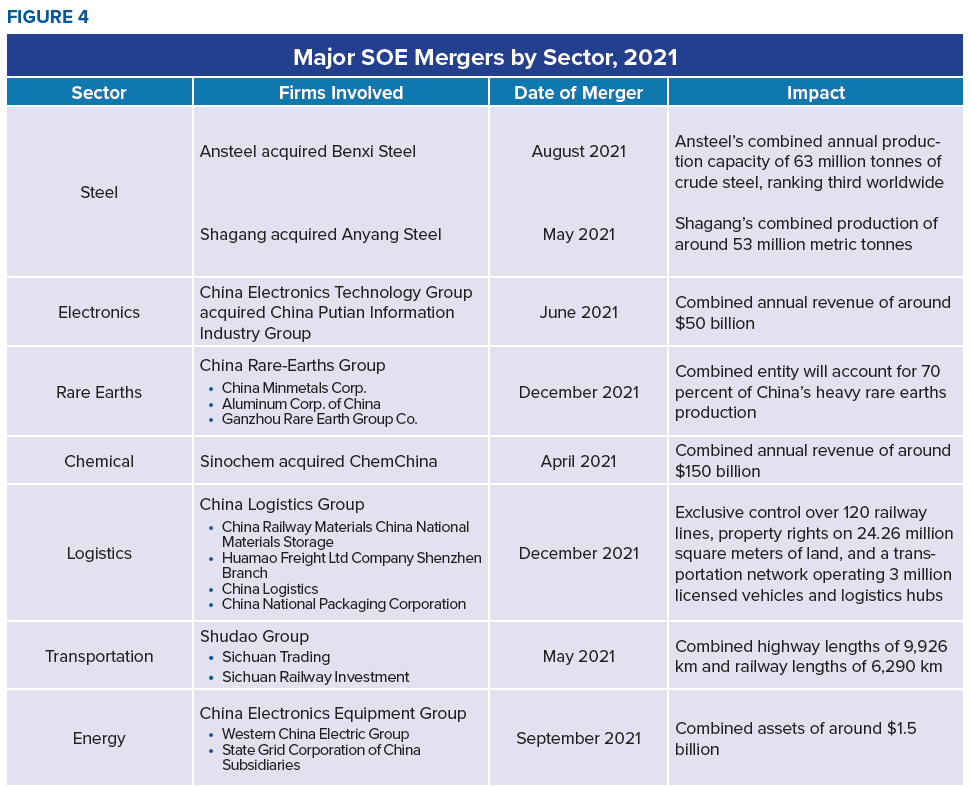

New mergers of SOE giants increased the concentration of market power and the risks that such power is abused in key sectors. In December 2021, China’s government approved a merger of three rare earths SOEs, paving the way for the creation of a “global rare earths giant.” This move reduces the competition between SOEs, enabling three firms to control 70 percent of China’s rare earths output and hold pricing power in the already-concentrated industry. It also runs counter to the Chinese government’s recent push to root out monopolistic practices and enforce fair competition for small- and medium-sized enterprises. China’s dominance in the global rare earths market means this merger would consolidate control over prices, with global implications for industries such as EV batteries and other clean technologies dependent on access to these minerals.

During the same month, China formally founded the state-owned China Logistics Group, merging five companies (most of which were state-owned) and expanding the new company’s logistics coverage to 30 Chinese provinces. China’s State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) and SASAC-managed China Chengtong Holdings Group will own the majority of China Logistics Group’s shares. The new logistics giant will have exclusive control over 120 railway lines, property rights on 24.26 million square meters of land, and a transportation network operating three million licensed vehicles and logistics hubs in 30 Chinese provinces and on five continents—an unprecedented concentration of government power. The two megamergers in Q4 were not isolated incidents—last year saw an acceleration of mergers, many involving SOEs (Figure 4).

Innovation System

At the end of 2021, the Chinese government released a flurry of development plans outlining goals for the country’s innovation system. These covered big data, green development in industrial sectors, and intellectual property protection. The documents contain high-level statements on growth and improvement in these areas, but little detail on how targets will be met and what defines progress in these fields. While it is too early to evaluate the plans individually as pro- or anti-market reform, the continued use of five-year plans (FYPs) to shape industry development indicates the government continues to believe it should determine which industries should grow and how innovation should be defined. For instance, the big data industry previously appeared in government documents that broadly discussed innovation and was featured as a category within the “Internet Plus” initiative, which was incorporated into the 13th FYP.

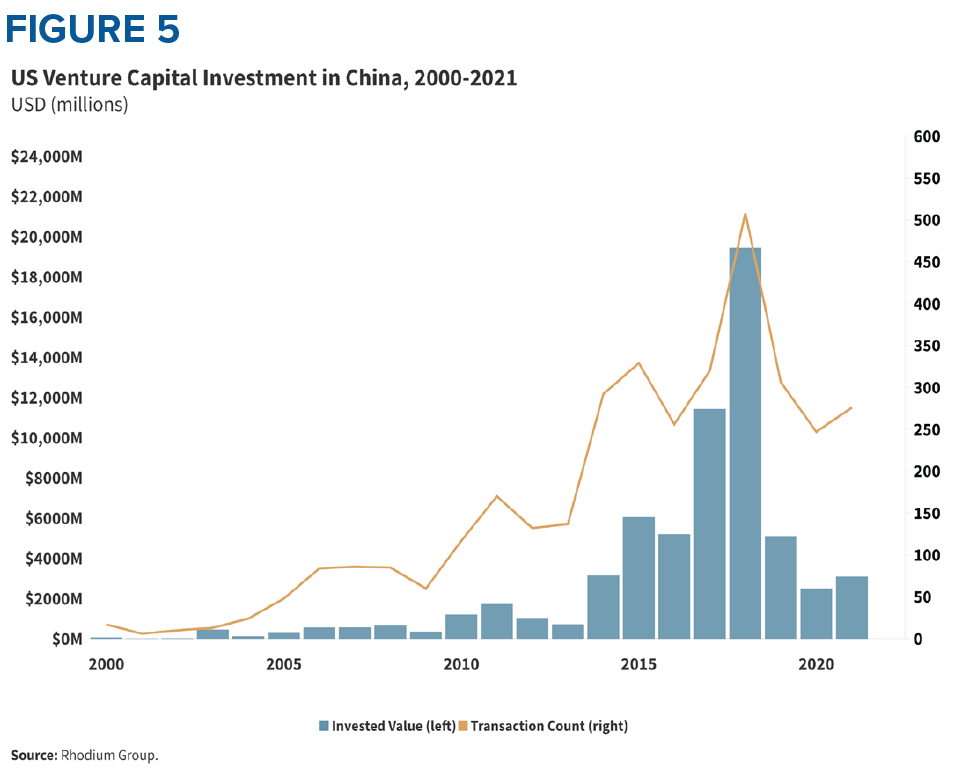

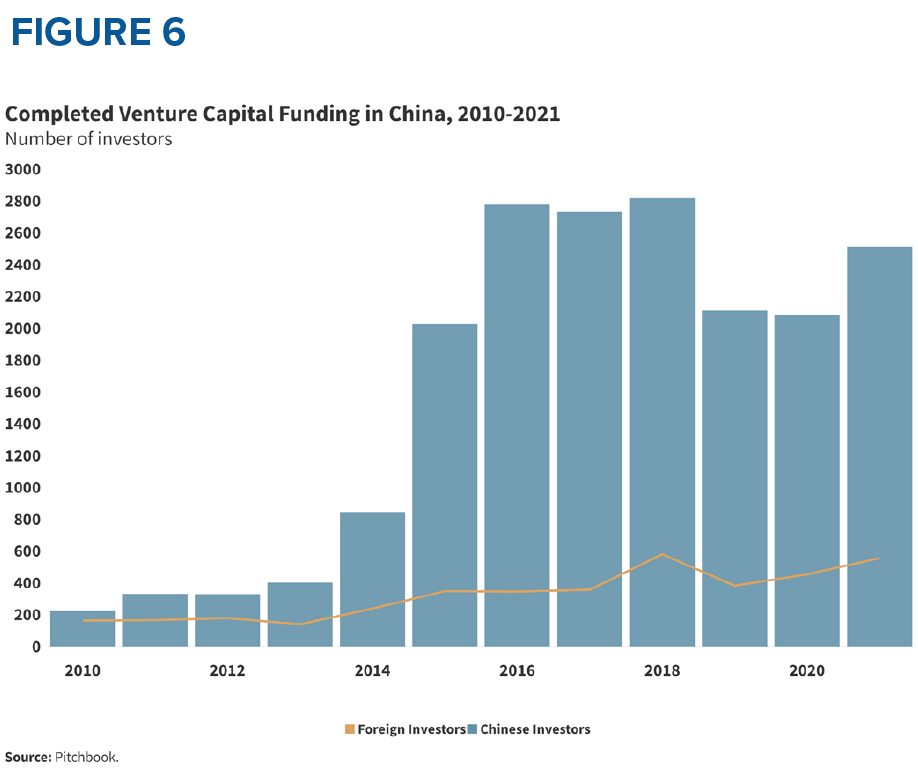

Big data’s appearance in its own FYP signals that the government has designated it for special attention and intends to closely direct big data development. In the long run, this may have a chilling effect on innovation, as companies will need to adjust their practices to meet national innovation goals. China’s tech companies have become one of the most vibrant segments of its economy, attracting international renown. Despite the regulatory storm, venture capital (VC) funding reached more than $130 billion in 2021, with US VC funding into China up 23 percent from 2020 (Figure 5) and the number of foreign investors in Chinese VC exceeding the 2020 total (Figure 6). However, the main targets for this investment were hardware technology sectors favored by Beijing, such as biotech, semiconductors, and robotics, instead of traditionally popular Internet sectors. The overall increase in VC investment also tells a macroeconomic story: as many market economies retained low interest rates due to the pandemic, investors sought high-yield investment options such as stocks and VC.

Openness to Investment

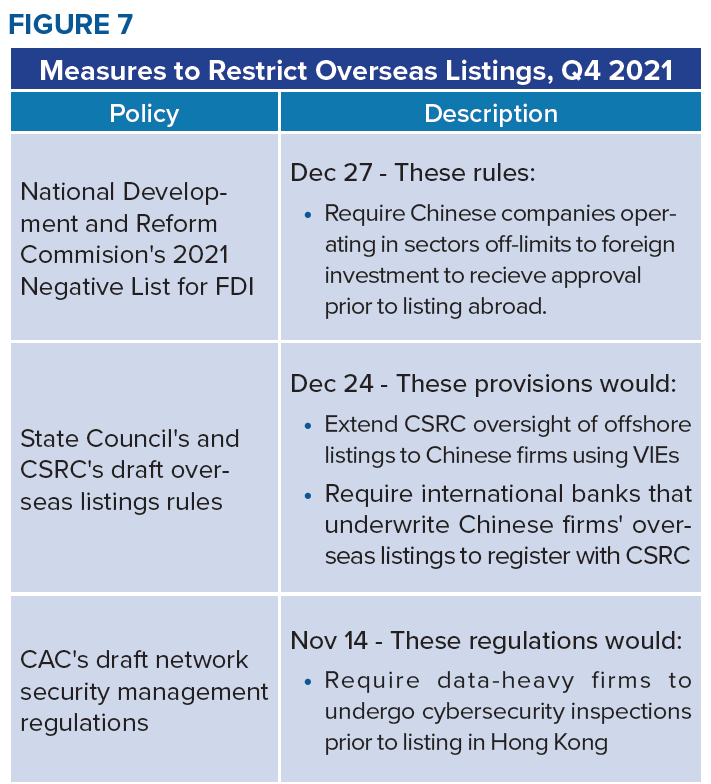

While there have been some positive signs this quarter for portfolio investment openness, including reforms that promote the broader use of derivatives instruments and relatively strong inbound portfolio flows, the regulatory activity that triggered the delisting of ride-hailing giant Didi Chuxing from the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) was a landmark event. On the regulatory side, the draft Network Data Security Management Regulations contain several provisions that could be used as a blunt instrument to discourage large, data-intensive domestic firms from listing abroad in the future. Clause 13 of the draft regulations would require firms seeking to list abroad to undergo security inspections if they handle data from more than one million users—which covers most of China’s prominent companies.

The China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) has responded to the concerns of investors, stating that it has no intention of imposing restrictions on foreign listings and promising cooperation with US auditing officials to meet compliance requirements. While an outright ban is unlikely, the decision by CAC to push Didi to delist demonstrates that, even without such a ban, many firms are likely to face data-associated restrictions to listing abroad through variable interest entities (VIEs). For Chinese firms already listed on foreign exchanges, the latest developments in China’s regulatory space could spell trouble if the firms run afoul of the strict data security parameters.

Special Topic: Didi’s Forced Delisting

In December 2021, the ride-sharing leader Didi announced it would delist from the New York Stock Exchange, only about five months after its initial public offering (IPO). Didi simultaneously announced plans to list in Hong Kong, with the promise that existing investors’ shares could be converted. Didi’s delisting comes after months of scrutiny from China’s regulators. The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) expressed concerns about data security and suspicions of the company’s use of foreign services for data storage, advising Didi not to go forward with the firm’s US listing until the cybersecurity regulator completed an internal security review. However, with approval from the CSRC, the regulator formally in charge of the listing process, Didi charged forward. Within days of its IPO, seven government ministries together announced investigations into Didi’s actions.

Didi’s conduct scrutinized from multiple directions: In the months between its IPO and ultimate delisting, regulators forced Didi to pull its apps from app stores and increase driver pay. Didi is also facing an anti-monopoly investigation over the acquisition of Uber China in 2016, which is ongoing. The crackdown wiped 25 percent from Didi’s share price and the company reported a 1.7 percent decline in its third quarter revenue. Didi tried to address the CAC’s concerns, even proposing to use a People’s Liberation Army-approved cybersecurity and cloud storage provider, but the cybersecurity regulator was not deterred. Ultimately, the CAC’s pressure resulted in Didi becoming the first Chinese firm forced by Chinese regulators to delist from an overseas equity market.

Is Didi’s forced delisting an isolated case or the start of a trend? The CAC’s rapid emergence as a super-regulator for all things related to data security signals that its approach has backing from the top. This will likely motivate other regulators to harden their scrutiny of China’s tech sector. As regulatory headwinds grow, the allure of an NYSE listing may fade for Chinese firms. In fact, seven Chinese firms shelved their plans to IPO on US stock exchanges in 2021. Ultimately, companies may come to see a domestic listing as a way to curry favor with increasingly emboldened bureaucracies.

Innovation and steering clear of the CCP’s red lines: Didi’s story sends a warning to private companies in data-heavy industries that running afoul of regulators will result in severe penalties, regardless of the company’s size. Beijing’s intervention in the Didi listing resets risk assumptions. It is no longer theoretical that the state might sacrifice economic dynamism in pursuit of what it perceives to be greater national security. Now, the question is how often and how far down the value-added ladder authorities will use these tactics. This alters how firms raise capital and share information, but no one can be sure yet to what extent.

China’s government has ambitious plans for the development of the digital economy—aiming to raise the proportion of the added value of core digital economy industries in its GDP to 10 percent by 2025, up from 7.8 percent in 2020. But Beijing’s decision to make an example of Didi has cast a shadow over the innovation scene. In trying to stay out of the government’s way, companies are likely to overcompensate, only entering sectors where the political economy outlook appears predictable. High-technology frontiers may suffer as a result. Burdensome requirements for companies may undermine for-profit competition, which is essential to innovation.

A Year in Review

Distinguishing cyclical state responses to extraordinary pandemic conditions from structural drifts away from market mechanisms was challenging in 2021, as governments everywhere resorted to emergency measures. But by year end, it was difficult to ignore evidence that China’s policies were taking the country in a more authoritarian direction, not least in economic terms. Officials in Beijing claim that this policy course is warranted given the special conditions in the country—though they also deny that the tenor of “reform and opening” has, in fact, ever changed.

Forced overseas delistings, extraterritorial pressure to shun Lithuanian suppliers, sanctions on moderate foreign think tanks for raising human rights issues, political threats against multinationals operating in China if they abide by home country laws—all these and other moves reflect a growing state role in steering economic activity. Insisting otherwise makes constructive dialogue about bilateral or multilateral management of systemic differences difficult, if not impossible. Little, if any, progress on economic policy issues such as trade, investment, or subsidies was achieved between China and advanced market economies in 2021. If China can only offer market access under carefully managed conditions or if it is consistently falling short of the reform expectations it has cultivated, then the future will be worse, not better.

Some economists worry that the risks of an economic crisis in China are rising rapidly and that this will reduce the government’s appetite for reform in 2022. Unless they change, Beijing’s self-satisfied zero-COVID policies will only increase the vulnerabilities of an economy that is already suffering from weakness in domestic demand, and further fray international supply chains. Each citywide lockdown to prevent the spread of Omicron takes another bite out of growth.

With China’s real estate sector—a key engine of national growth—in meltdown, China’s domestic economy is already in financial distress. All of this will have trade implications. China will import less for construction, and its vast exports—almost $3.4 trillion in 2021, half the value of all industrial sector output—can only subside, as global demand shifts away from goods and towards services. Exchange rates will move to reflect new realities, as will interest rates as the investment landscape changes. How does this shape China’s outlook and options for 2022? The CCP’s calendar is bracketed with two milestones: the National People’s Congress in the spring and the Party Congress in the fall—meant to fête the Party’s achievements and anoint Xi Jinping for a third term. On current trajectory, those meetings may be more emergency planning councils than celebrations.