China Pathfinder Update: Lack of Policy Solutions in Second Half of 2023 Belies Official Data

In the second half of 2023, Beijing's efforts on market policy reorientation were limited.

Through the second half of 2023, the gap between China’s impressive official data and visibly underwhelming consumer demand, unresolved local government debt problems and an unprecedented drop in foreign direct investment was stark. The China Pathfinder framework scans for evidence of market policy reorientation to fix these problems. But in this coverage period (July–December 2023), Beijing’s response was limited. Officials redoubled efforts (and incentives) to encourage foreign investment and trade, pledged to loosen cross-border data transfer rules, and increased deficit spending limits to stoke anemic demand. China’s government also simultaneously threatened economists with consequences for even talking about bearish signals and discontinued unflattering economic data, severely aggravating credibility concerns. Policymakers did next to nothing to tackle the real structural problems. Though we expect the severity of 2022–23 declines to set China up for a modest cyclical rebound in 2024, long-term growth potential will disappoint until fundamentals are addressed.

China’s Macro Story: Policy Directions Coming into 2024

A first quarter 2024 stocktaking of China’s economic policy and growth outlook is made difficult by the murkiness of the 2023 picture. In the first quarter of 2023, recovery was expected, but doubts arose by the second quarter. By the second half of the year, confidence had broken down entirely, as we discussed in our October 2023 Pathfinder Annual Report. The debate over why China is slowing continues, even while the cycle is bottoming out.

The difficulty is that official Chinese statistics have still not conceded this reality. Through the end of the year and start of 2024, Beijing continued to claim performance above the 2023 target of 5% GDP growth, despite a running battle to roll out extraordinary support measures including lifelines for property developers, mid-year expansion of the fiscal deficit ceiling, monetary policy easing and other steps, and unexplained distortions in the national accounts data. As 2024 gets underway, new emergency steps to prop up stock markets are being added to the mix, yet another sign that all is not well.

Beijing was not alone in telling this hopeful story. In late 2023, the IMF and other international organizations published the same rosy picture of conditions that Beijing painted, even upgrading their forecasts on the grounds that consumer demand was thriving. This is a problem because the vast majority of people who hear these “forecasts” assume they are independently calculated, whereas they are generally not: they are better understood as forecasts of what Beijing plans to announce.

This politicized picture of economic activity, shaped by repeated state interventions to suppress data and disincentivize independent analysts, grew more confusing still at year’s end. Because the downturn had been so much more severe than the data showed, China was approaching a modest cyclical bounce despite lacking real structural reforms. This doesn’t make sense if you believe the official data saying that growth was on target. A 2024 recovery is possible, but only because property fell almost 60% in just two years.

As we progress into 2024, these nascent signs of life in previously moribund sectors will at first be disbelieved by observers late to the China slowdown conversation, who are loath to be caught wrongfooted again. As we have stressed, credibility built up over decades let Beijing manage expectations even while the drivers of China’s growth were shifting. But credibility is not inexhaustible. In 2023, the disconnect between official numbers and performance indicators reached the breaking point, triggering the wave of recent commentary. In our future Pathfinder updates we expect to discuss how hopes are bolstered by improved property data. That recovery will be real, but cyclical and transitory. Long-term stability will still require urgent market reforms, and the present danger will be that recovery makes the pain associated with real reform harder to justify.

In the remainder of this China Pathfinder update, we look for notable policy moves in the second half of 2023 in the six core market economy domains we track. For each, we remind the reader what significant structural reforms would look like if they happened. Following that policy review we finish with what to watch for next in 2024.

July–December 2023 Policy: Courting Hearts, but Not Minds

Financial System

In the second half of 2023, financial system policy focused on improving domestic and foreign business sentiment, but did not treat the underlying causes of financial stress. In October the National People’s Congress Standing Committee approved a revised government budget, raising the fiscal deficit ceiling for the year from 3% to 3.8% of GDP. The surprise mid-year revision, which last occurred during the Asian financial crisis, increased central government bond issuance by RMB 1 trillion. This was an attempt to lift the real economy and boost sentiment in Chinese equity and commodities markets without adding to local government debt—the central government bears those obligations, but local governments will spend the proceeds. The move made plain that authorities perceive major shortfalls in GDP growth.

At the same time, media reports hinted at a refinancing policy package to address local government debt problems, though the measures have not been formally announced. The basket of policy measures would involve extensions and rate cuts for local government financing vehicle (LGFV) loans. This move puts maintaining near-term financial system stability above long-term growth, because it risks “zombifying” banks by assigning this burden to them. November 2023 reports suggested that a RMB 1 trillion increase in pledged supplementary lending (PSL) for urban redevelopment would also occur. People’s Bank of China (PBOC) data show RMB 350 billion of this in loans to policy banks were made by year end. Presumably the rest will show up in 2024 to support property construction.

These policy moves resemble those applied in 2014 and 2015 to deal with the property sector, weaker growth, and LGFV debt. Once again, this only kicks the structural can down the road, and lacks what is needed to address systemic issues. Structural problems require structural reforms. A public acknowledgment of and commitment to restructuring LGFV debt and recognizing losses would show seriousness and transparency. Real tax reform to address central-local fiscal imbalances is also crucial, together with the other side of the fiscal coin: public expenditure reforms that wind down unproductive spending that impedes marketization and reprograms outlays for human capital investments and consumption support.

Market Competition

Chinese policymakers made welcome efforts to improve market sentiment in the second half of 2023, but the benefits remain limited by a lack of structural changes. The State Council invited public input on obstacles to private sector investment, including market entry barriers, unfair competition, and arbitrary fines. Local officials were instructed to intervene directly in serious cases of interference with private interests, or supervision teams would be deployed. The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) announced a new bureau to streamline bureaucratic processes for and communications with private companies.

Officials reassured industry that controls on cross-border data transfers would be rationalized and relaxed. The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) is considering exempting certain areas such as cross-border manufacturing, international trade, and academic cooperation from data export security assessments, when personal information or “important” data are not involved (though “important” is ill-defined and leaves many questions open). Some instances that require the transfer of personal information—visa processing and cross-border shopping, for example—may also no longer need security assessments. However, the CAC was unable to finalize these relaxations by year end, leaving firms, and especially foreign companies, to contemplate more of the same uncertainty about the business environment. The rising weight of political ideology in policymaking depresses business investment by Chinese and foreign firms alike, because it reduces the net present value of business opportunities by adding unmanageable risks.

Exactly one decade prior to this review period, President Xi Jinping announced actions to make the market decisive in resource allocation, downsize the role of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and tackle dozens of structural challenges. Talk about restraining the state is nowhere to be heard today. As data security regulations and standards are refined in 2024, ensuring equal treatment of foreign companies would inspire more confidence in competition policy conditions. Likewise, credible national income and GDP statistics are an acid test of intent to have a market economy and growth. Current practices continue to indicate that politics, rather than transparent data, are driving how market competition performance is assessed.

Innovation

China’s innovation environment saw mixed results in the second half of 2023. The CAC released interim measures on generative AI, which softened more restrictive draft regulations released in April. Under the new rules, only providers who want to offer services to the public, unlike enterprise-facing products, would need to submit security assessments. The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology also published a draft plan to develop robust standards for the Internet of Things (IoT) by 2025. While the document stated that domestic standards would be developed in line with international IoT standards, it made clear that China intended to play an active role in setting those standards. The National Data Bureau introduced a three-year action plan, focusing on data application in key industries and setting ambitious 2026 growth targets.

Toning down draft measures on AI management was a positive development, but state industrial policy activism is on the rise. In this period, four large generative AI models passed a government assessment, which gives them a leg up in China’s AI race. With government-sponsored language models dominating the industry, Beijing is anointing winners, which reinforces government control over a nascent sector. More strident guidance on data use targets for industries and local authorities also leaves less and less room for the market to play a role, let alone a decisive one.

In 2024, the mood at innovative firms is somber because state sector damage to dynamism has been severe and will be difficult to reverse. Credible policy signals would need to convince anxious private companies, foreign businesses and venture investors that market driven innovation will not only be tolerated but promoted. Clear definitions and practical examples of what “important data” means in the CAC’s “toned-down” cross-border data flow regulations would encourage investment. China-world value chain derisking driven by rising security pressures is also reducing room for technology transfer and therefore hurting the innovation outlook. There are conciliatory steps Beijing could take to arrest that trend, such as tempering brash foreign policy postures, but no one is expecting such a pivot.

Trade

China’s trade openness contracted in the second half of last year, marked by increased controls. Trade dragged on GDP growth in the second half of 2023, despite surging exports in some sectors that are fueling foreign concerns about dumping and spillovers from Chinese overcapacity. Exports of electric vehicles, lithium-ion batteries, and solar products to the EU took off in 2022 and remained high through 2023. China maintains domestic subsidies and supply-side policies, while policy support for consumer demand is decried as welfarism, an asymmetry that leads to overcapacity, aggravating trade imbalances. Rather than acknowledge the unfair implications for producers in other nations and propose some sort of voluntary export restraints, Beijing emphasizes the decarbonization potential and appeals to anxiety regarding global warming.

Parallel to these exports, China imposed export controls on key intermediate inputs for EV batteries, semiconductors, wind turbines, and other technologies. The curbs on graphite, germanium, gallium, and the technology used for making permanent rare earth magnets—for all of which China is the top producer globally—would make it more challenging for other countries to diversify their supply chains. The Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) and Ministry of Science and Technology jointly invoked national security concerns in rolling out export controls on drones, laser radars, and technology used for making optical sensors, among other items. These measures are ostensibly in reaction to US controls on equipment exports and chips related to China’s high-end semiconductor sector. At the end of 2023, China announced the end of tariff cuts on 12 chemical imports from Taiwan, and accused Taipei of violating WTO rules, while also rescinding tariffs on Taiwanese grouper and Australian meat and barley. The tariffs on Taiwan chemicals resumed at the start of 2024, just prior to Taiwan’s elections. China’s use of economic statecraft and political influence over trade policy are not likely to change soon.

There is ample room for Beijing to change this impression by stepping up reporting of subsidies to the WTO, or eliminating existing trade coercion measures. Specific actions that would indicate greater trade openness include moving away from the practice of raising or lowering the value-added tax, which distorts global crop markets; revising China’s decrees on food imports, which were implemented in 2022 and required the registration of all foreign food manufacturers; and publishing data on how Intellectual Property Action Plans have been enforced. This would demonstrate effort to achieve fair and transparent trade practices, outside of the more common trade opening measures such as adding free trade zones that China has adopted.

Direct investment

Through September 2023, foreign direct investment (FDI) flows to China were down a whopping 34% year-over-year, the most substantial fall recorded by MOFCOM. China’s foreign exchange administration also reported direct investment liabilities declining by $11.8 billion in Q3 2023, turning negative for the first time since the data were collected starting in 1998. The commerce ministry reported actual utilized foreign capital from January to October 2023 decreasing 9.4% year-over-year. Yet MOFCOM offered a positive spin on the data, highlighting an increase in the number of foreign-invested enterprises, and focusing on the sectors that saw FDI growth. This continued pattern of downplaying bad news for inbound FDI is unhelpful to confidence building.

While limiting negative reporting about H2 2023 FDI trends, officials worked to restore foreign investment flows, especially in services. A State Council plan with 23 tasks to boost Beijing’s services sectors released in November was followed by the Central Economic Work Conference in December, which pledged to boost foreign investment in sectors including telecommunications and medical services in 2024. This included a plan to lift foreign ownership caps in specific sectors. China’s Commerce Minister Wang Wentao said China would remove industries from the negative list for foreign investment. To further improve the environment for overseas firms, the State Council issued opinions calling for foreign invested enterprises to have increased participation in government procurement activities, a long-standing goal for foreign companies.

Several of these measures are meaningful for direct investment, though they seem more a reaction to terrible data and economic headwinds than a considered shift toward a market-driven system. Beijing can further demonstrate commitment to attracting foreign investment by removing the threats and intimidation directed at foreign due diligence professionals last year. Expanding the more market oriented terms available in China’s free trade zones and ports beyond the current six to the broader economy would be compelling. Similarly, expanding the number of cities that allow “general data” to move across the border (currently only Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai are in consideration) would resolve many FDI concerns.

Portfolio investment

In the second half of last year, Beijing’s support for capital markets took three forms: bolstering demand, reducing supply, and lowering transaction costs. The broad spectrum response was necessitated by heavy portfolio capital outflow pressures brought about by a yawning interest rate gap with the US and other market economies. On the demand side, in October China’s Central Huijin state investment fund bought ETFs in an attempt to stabilize stock markets, while in December, China Reform Holdings Corp (another state-owned strategic investor) purchased tech-focused index funds. Beijing also allowed social platforms such as WeChat to direct retail investors to the stock market.

On the supply side, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) has slowed the pace of initial public offerings (IPOs) and imposed tighter restrictions on refinancing activities for listed companies that are underperforming. In an initiative to protect small investors, the CSRC tightened rules on share sales by large shareholders of listed firms and increased scrutiny over program trading to address market volatility concerns. At the close of 2023, the CSRC imposed a ban on mutual fund managers selling more shares than they bought daily for market stability. The ban was lifted at the start of 2024, but before the end of January it appeared to be back in place, along with other measures to stabilize capital markets through government intervention.

In an effort to reduce transaction costs, China halved the stamp duty on stock trading and reduced transaction handling fees submitted by brokers to the exchanges. Chinese stock exchanges also lowered margin requirements to boost investor financing. Additionally, under regulatory guidance, mutual fund companies in China reduced management fees for equity funds.

In contrast to these efforts artificially shaping supply, demand and prices in portfolio investment flows, a structural approach to improving portfolio market performance would emphasize efficiency over ideology, market discipline over administrative solutions to stock exchange problems, and credible constraints on political interventions. China had the world’s worst performing major stock markets in 2023. If portfolio flows are to be marketized and help support China’s long-term growth, Beijing will have to learn to live with less control over private capital, and to respect the political discipline imposed by the prospect of capital flight.

Policy Directions Across China’s Economy: The Big Picture

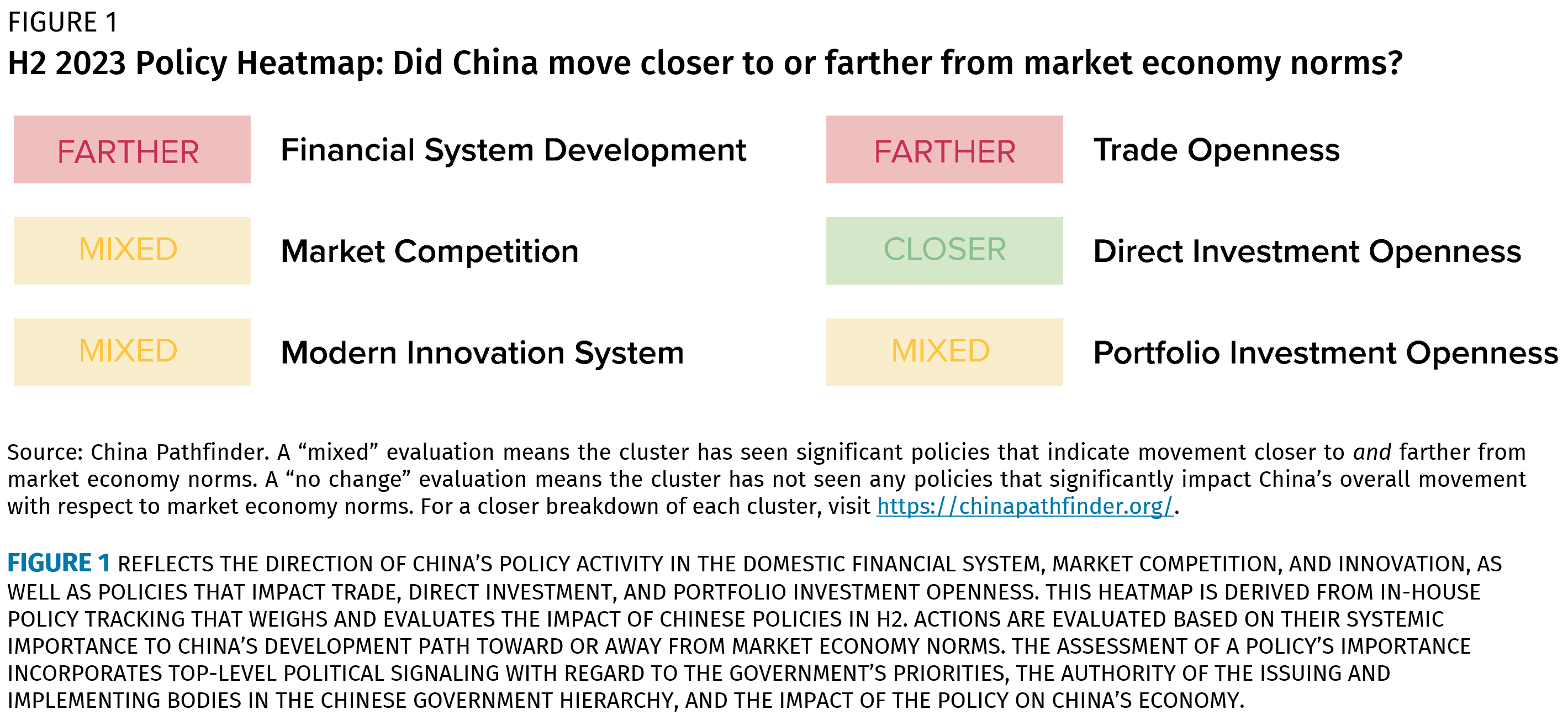

In H2 2023, Beijing’s moves to maintain its narrative of economic growth meeting official targets and reassure investors ran counter to a lack of needed structural reforms in the financial system, market competition, innovation, and trade. The progress toward or away from market economy norms is systematically tracked in the heatmap below (Figure 1).

What to Watch in 2024

Over the past decade, China cycled from “decisive market reform” to the post-COVID faith-based expectation that recovery would just happen. That did not pan out. Though official statistics still deny that miss, as seen in the January 18, 2024 preliminary growth statistics, it is probably the case that policymakers—including President Xi Jinping—are getting the message. We will likely see a change of conditions in 2024, driven by the combination of urgent support efforts described above and the reality that all bad things must come to an end, including the property sector collapse. Importantly though, this will be a cyclical reprieve, not the end of China’s travails.

First, in the quarters to come, property will shift from a massive drag to a modest boost to GDP growth—though from a much lower base. We expect this stabilization due to the three years of destocking that have already taken place, bringing the real estate industry near a long-term equilibrium level of activity.

Second, there is a reasonable likelihood that policymakers will try to use this breathing room to get more reforms on track, rather than defer them further as in recent years. Look for signals of this at the February China Development Forum gathering, and the Two Sessions in March. As of this writing, no plans of a Third Plenum—the traditional twice-a-decade gathering of the Central Committee where decisions on China’s economy and reform agenda are usually made—have been announced, but it is reasonable to expect that this will occur in the first half of 2024 as well.

Third, while cyclical conditions will stabilize this year, Beijing must soon acknowledge that slower growth, in the 3% or 4% range, is here to stay. On the one hand, this may lead to more modest geoeconomic ambitions like the Belt and Road Initiative, as leadership will be focused on the transition from investment- to consumption-led growth at home. On the other hand, lower growth will bring spillovers. For instance, lower Chinese demand will impact foreign firms in industries that rely on China as an importer. Some foreign firms will be edged out by lower-priced Chinese competition as Beijing boosts domestic manufacturing, like in lithium-ion batteries and other renewable energy products.

Fourth, China will continue to face weak exchange rate conditions, as PBOC balance sheet operations will remain the main mechanism for the central bank to inject liquidity into the banking system. Capital outflows are expected to continue in 2024, with further normalization of international travel and a continued, though narrower, interest rate gap to the United States’. This may contribute to RMB depreciation.

Finally, Beijing’s capacity to influence growth via government spending will remain constrained by local fiscal stress and an already burdened monetary policy. Traditional fiscal policy channels could be unclogged by higher central deficits and the modest return of land sales to property developers, but a positive fiscal impulse is not assured. The central bank risks weakening the RMB further if it cuts interest rates. In January 2024, the PBOC’s decision not to cut rates for one-year policy loans suggested that this is already taking place, to the disappointment of investors anticipating support for the economy. Bank reserve requirement cuts have been employed instead to improve near-term liquidity; however, as of this writing, concerns about Beijing’s room to support demand are still rising.

Acknowledgments

Written by Daniel H. Rosen and Rachel Lietzow.

The authors wish to acknowledge the members of the China Pathfinder Advisory Council: Steven Denning, Gary Rieschel, and Jack Wadsworth, whose partnership has made this project possible. Niels Graham and Jeremy Mark were the principal contributors from the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center.