China’s GDP – 2015 Target and Outlook

China just released preliminary 2014 gross domestic product (GDP) results. At 7.4% they missed their annual target (7.5%) by a mere breath – not a huge deal practically, but significant symbolically. More important is the composition of this growth. Consumption is playing a bigger role, as investment falls from former growth rates. Services activity continues to rise relative to heavy industry. These are positive signs. Beijing is whispering a 2015 GDP target to friends and thought leaders: the number we are hearing – 7% “or thereabout” – would reflect doubling-down on nascent reforms. We extrapolate the most likely pattern of 2015 expenditure growth to see what 7% growth on top of the 2014 base would look like. This target portends one trillion dollars in new Chinese activity at the margin on top of 2014 output. Ask yourself: where will that come from?

2014 in the RearView Mirror

In January 2015, China reported a respectable 7.4% GDP growth for 2014, barely missing Premier Li Keqiang’s decreed 7.5% target, but still defying predictions of an inevitable, deeper slowing. This performance comes after an upward rebasing of 2013 GDP by 3.4%, following the most recent once-every-five-year economic census, so whatever growth was achieved was from an even larger underlying foundation. With an additional $800 billion in annual output, China joined the United States as the second member of the 14-digit club – more than $10 trillion in headline GDP – drawing China closer to becoming a peer competitor with the United States, despite a year of painful economic restructuring, harrowing political showdowns at home, and an external environment fraught with geopolitical risks and fragile recoveries.

The drivers of this growth are changing. Services activity outpaced overall GDP with 8.1% growth in 2014, in real terms, and rose by 1.3 percentage points to reach 48.2% of total GDP. Beijing’s official data say 2013 was the first year services surpassed the secondary sector – including industry and construction – to become China’s largest sector, an important milestone for an economy long over-dependent on investment and heavy industry, and now betting on untested intangible sub-sectors to deliver future jobs, taxes, and returns. Our recount of China’s GDP (see Broken Abacus, in partnership with CSIS: forthcoming this spring) concludes that services value-added actually exceeded secondary activity by 2009, when properly counted. Values for transportation, information and communications, wholesale and retail trade, and real estate should all be augmented.

Was last year’s “rebalancing” attributable to new structural reforms or simply to better accounting then? A little of both. The final 3.4% adjustment was only a fraction of the necessary revision if all current national accounting shortcomings were addressed. At least a little credit for this initial rebalancing must therefore be granted to the Xi leadership’s reform efforts. Besides helping Beijing claim some initial policy success, continuing services growth is also essential for mitigating the employment pressures hanging over leaders’ heads. Each unit of investment in services generates far more jobs than deploying capital in heavier industries and rising services output correlates more closely with household consumption. Seen in this light, China’s 2014 growth story is not about coming up a fraction shy of a reference target set a year ago, but about green shoots of progress toward the goal of transition to higher value-added, cleaner, more labor-intensive growth in a “new normal” era.

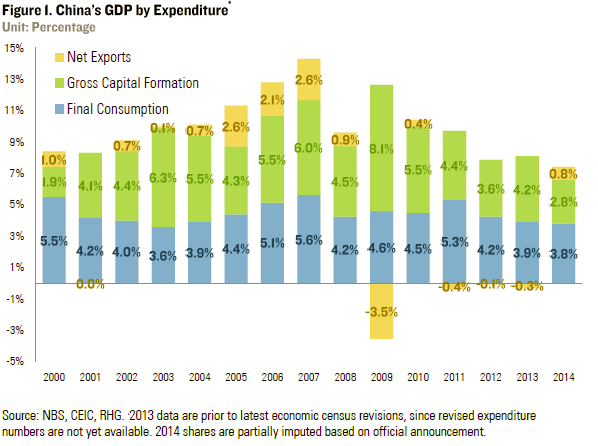

The mix of investment and consumption in the composition of China’s GDP moved in the right direction last year. Final consumption expenditure – government and households combined (the breakdown is not available yet) – contributed 51.2% of 2014 GDP growth: still low, but improved by three percentage points from 2013. Net exports played a critical part in delivering China’s 2014 growth performance, after the previous three years of negative contributions. But the relative discipline on investment was the real story: if you got that right for the year, you got the basic China structural story right for the year. Not everybody did, with many expecting Beijing to give in to the seduction of palliating worries with easy credit in 2014. Extrapolating from other data (Beijing has yet to release 2014 gross capital formation figures, which are necessary for a proper estimate of investment in GDP) we find that a mere 2.8 percentage points of the 7.4% headline growth, or 38.3% of new economic output above the 2013 base, was thanks to investment growth. That is the lowest share since the first quarter of 2013, and the lowest on an annual basis since 2000. President Xi’s reforms deserve some credit for that too; with state banks crying for easier credit nearly every day of the year, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) could not have held the credit line as well without support from the most senior leadership.

Since both the industry- and expenditure-based pictures of China’s economy are showing these healthy rebalancing tendencies and Beijing has already moved to rely less slavishly on annual growth targets, some may ask whether China still needs a target. We turn to that question, and the outlook for the year ahead, next.

Rationale for the Growth Target

In mid-December 2014 Xi Jinping, Premier Li, and other officials gathered in Beijing for an annual economic work conference. They set goals for managing the extent of monetary and fiscal loosening to keep the economy afloat, which were only partly communicated to the public to maintain a degree of tactical ambiguity in the markets. They enshrined Xi’s doctrine of “the new normal”, a term the President has employed since early last year to emphasize that current growth rates do not reflect an output gap and will not be the bottom of a range, but closer to the middle; the focus must remain on the quality of growth not the quantity. They also decided upon a growth target for 2015, such as China has issued annually since the mid-1980s. This was not announced; by convention it will be announced this coming March around the annual sessions of the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. The number that will be announced, we surmise, is either 7% or a range of values clustered around 7%.

As discussed above, the 2014 target was set at 7.5% after considerable internal debate that included arguments in favor of not offering a target, in favor of a range, and in favor of a lower target. The drama of coming in below the target for 2014 and the negative press it fostered (“China misses target with lowest growth in 24 years!”), may have chastened leaders and made them inclined to set a lower bound or range rather than a point target.

But why does this even matter anymore? It would be great if we were at a stage of China’s economic development where it did not, but the reality is that such maturity has not yet been achieved – or so leaders conclude. There are at least three reasons why the growth target is still perceived as important and will be continued.

First, a number of fiscal budgeting lines are based off annual GDP level or growth. This is a legacy of the planned economy era in which the scale of growth was chosen, rather than being an organic outcome. Thus, certain accessories to growth had to be set in advance by economic engineers. Examples include education, science, agriculture, social security and health care spending. There is no reason why provisioning for these expenditures cannot be separated from a central growth target in the future: this is an element of the center-local fiscal reform process we have written about before. But the preliminary work to enable better fiscal planning is not finished, so the old “training wheels” approach of keying off a national target remains necessary. If you’re thinking that it is a bad idea for basic, long-term fiscal systems to be entangled with the political needs of short-term signaling on GDP growth, we agree.

Second, the official growth target is as clear a guide as any to whether the leadership believes the economy is operating at potential or suffering from an output gap. In the fourth quarter of 2014, debate between state financial firms and their regulators on China’s macro performance remained tense. Many state owned banks, not to mention the myriad financial firms below them, argued that China was growing below potential. The chief economist of one of the biggest said in November that “it’s common sense…that 7.5% is below potential. The demographic is not fully employed.” A senior PBoC official, countered in the same dialogue that, “No. There is no general output gap in China.” The output gap is, of course, a euphemistic way of talking about whether the PBoC should loosen liquidity to sate the voracious appetite of banks for capital to lend and generate fees on. State banks have continued screaming that rates are high relative to the accommodative levels needed to sustain business as usual. PBoC’s response (as it was in November), was that, “interest rates may be a little high, but not significantly. There is only very limited room for loosening. There are other ways to lower the cost of borrowing.” The PBoC remains more concerned with the rising burden of adjustment that is building up even with a neutral monetary stance – let alone under an accommodative one.

The national GDP target for the year is an obvious reference point for determining who is right in this shadow play. Of course there are many factors other than a careful analysis of current potential that go into the growth target, such as managing social expectations and building public confidence in the government. Different actors will refer to it for different reasons, depending on their interests. Setting it at 7% in 2015 and tying those expectations to the “new normal” messaging would be a step towards more sustainable growth, and – make no mistake – a planned deceleration from a target of 7.5% to 7% just one year later is a bold embrace of reform realities in the Chinese context.

Notably, after the December economic work conference, quasi-official Chinese economists shifted from referring to the outlook for PBoC’s monetary policy as prudent or neutral to describing it as guided by “targeted action to be net expansionary”. PBoC’s official position on this is a “neutral and moderate” monetary policy for 2015, which combines a prudent bottom-line stance and targeted credit tools to facilitate economic restructuring and industrial upgrading (the “moderate” part, as in moderately accommodative, is new). To many this sounds ambiguous or contradictory. It allows PBoC to claim the emphasis is on the tight monetary stance, but preserve flexibility for restructuring and reform. PBoC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan told World Economic Forum audiences in Davos that the Bank did not intend to provide “too much liquidity”; rather, its principal role was to maintain a stable policy environment. But no doubt the overseers of industrial policy at less public Beijing podiums were simultaneously telling industry that looser credit was headed their way; indeed, press reports of RMB 600 billion China Development Bank loan packages to Fujian province for the next five years are already circulating, along with many other indications of “stimulus-light”.

The fact that Beijing is planning for a slower 7% growth in 2015 amidst this more accommodative credit stance amplifies the reality that neither investment growth nor net exports growth as we’ve known them can deliver the results China counted on in the past. That leaves consumption growth. While household consumption holds massive promise, it differs from investment and trade growth in China in this important respect: it cannot be so easily delivered through government edicts and interventions like stimulus or exchange rate distortions.

Which brings us to the third role the growth target plays: as a demonstration of central authority. Headline GDP growth rates have been cut in half over the past eight years, from 14.2% to 7.4%. But with results always surpassing expectations set well in advance, the narrative has generally emphasized China’s strength, not weakness. To bet against China is to bet against a regime with options which has almost always made its targets. Since the beginning of growth targets in the mid-1980s China has only missed twice: after the Tiananmen crisis of 1989 and the Asian financial crisis of 1998. So what is the crisis today?

Even the most aggressive speculators are cautious not to get in China’s way. This control is important for disciplining not just markets, but China’s own provinces as well. Provincial officials are still judged by the growth results they turn in, though there are efforts afoot to alter that. What is outperformance and what is reckless abandon? Without an efficient local government bond market or similarly objective means for answering that question, the great majority of local officials will err on the high-side and gun for faster growth. The national GDP target is therefore an important reference point for sub-central fiscal behavior. Without a central target, there is no universal benchmark against which to calibrate provincial activity – both in terms of real activity and for making the national accounts add up at the end of the year when the gap between provincial and national production figures is assessed.

Finally, the central authority displayed by growth targeting has been an important geo-economic tool for Beijing on the foreign policy front. By sticking to a growth target, China demonstrates to other nations – especially those with big domestic fixed investment outlays required to service China’s appetite for raw materials and inputs – that it offers a more predictable beacon than advanced economic incumbents. While Europe and Japan bounce around, and the United States is haunted by the constant specter of economic disruption driven by political discord, Beijing offers GDP assurance – at least on paper.

As discussed above, Premier Li’s “read my lips: 7.5%” pronouncement of mid-2014 came up modestly short, and the symbolic power attached to the number on the right side of the decimal point was significant. Chinese economists are defensive of the notion that global oil price weakness reflects – in part – misgivings about China’s outlook. Oil is complicated. But commodity prices for rubber, bitumen, copper, lead, and iron-related inputs – to offer just some examples – have all fallen in recent years in line with China’s growth outlook. China’s ability to publish a credibly bullish growth expectation is critical to producers of all these inputs; but credible and bullish are not compatible anymore in terms of what that target looks like.

2015 GDP Outlook

After the growth target discussion above, one might think there is not much left to say about the outlook: 7%, plus or minus a few tenths. But, in fact, there are four questions about China’s 2015 GDP growth that deserve attention: will they make it, what will it be composed of, what price will be paid to get there, and will it be true? We will touch on each of these briefly.

First, Beijing said “around 7.5%” in both 2013 and 2014, and came in at 7.7% and 7.4% respectively; if Premier Li decrees 7 +/- 0.2% in 2015, is there any reason to doubt he can deliver it? Not really. This deceleration trajectory – 7.7, 7.3, 7ish over consecutive years – is closely aligned with our long-term projection of potential growth with Chinese characteristics, as laid out in our fall 2014 work on China’s reform program and 2020 goals. Bloomberg’s grouping of several dozen predictions presently shows a mean (and median) of 7%, with 40 of 42 predictions between 6.7 and 7.3%: few contrarian views here! Importantly, despite an overall augmented debt to GDP ratio north of 260%, everyone generally accepts that Beijing has room to spend if it wants to prop up results this year; leaders are making clear that there is a limit to the slowdown they will permit. So far they say that employment is solid, despite the slower headline numbers, precluding the need for more stimulus. But, as noted, a more accommodative stance – fiscal and monetary – has been evident for the past month. Physical indicators, like import volume of iron ore, crude oil, and coal spiked back up at the tail end of 2014, in response to expectations of demand from infrastructure projects green-lighted in December – a reminder of what Beijing can still do.

Second, the composition of China’s 7% growth continues to evolve, as discussed above in terms of 2014 performance. At the macro level, services sector output (value-added) exceeded industrial and construction activity in 2013 by official accounts, and by 2009 according to our Broken Abacus study, as noted earlier. Leaving aside questions about statistical accuracy until the end of this note, the rise of services – the fastest among all three sectors in 2014 – helps resolve a paradox: how can employment be as strong as Premier Li claims if investment and GDP growth are slowing? Simple: GDP is slowing because capital-intensive investment (thus, expenditure-based GDP growth) in heavy industry that creates few jobs is slowing, while services, which use less capital and create more jobs, are growing. A headline value around 7% for GDP growth is consistent with employment requirements, provided reform continues to open room for new activity, especially in the services sector.

The short-term, one-year outlook is usually analyzed in terms of growth in the expenditure components of GDP (Figure 1). China’s 2014 GDP was $10.4 trillion. For China to deliver 7% growth on that base in 2015, it will need to add about one trillion dollars (at current exchange rates) to that level of output: one year of marginal Chinese growth is more than half the entire Indian GDP.

A trillion dollars in new activity is a lot of demand: where is that going to come from? Let’s consider each component.

Growth in net exports played a big role in 2014, but is unlikely to do so in 2015. China’s full-year goods trade surplus grew from $259 to $382.5 billion in 2014 – a $123.5 billion upswing that reversed a three-year run of negative contributions. This was the result of weak domestic Chinese demand, a relatively stable external demand picture (especially from the United States), and to a great extent from lower import prices. At today’s prices versus six months ago, China’s annual oil import bill would be $100 billion lower, adding to net exports and, hence, GDP growth. In its latest World Economic Outlook, the IMF projects cheaper oil to add 0.4 to 0.7% to China’s 2015 GDP (versus 0.2-0.5% for the United States). China’s industrial demand should recover mildly in 2015, thanks to government-driven infrastructure investment and other stimulus, moderately increasing both the value and quantity of imports. This should help restore global commodity prices, to some extent, while foreign demand for China’s exports will be stable or mildly stronger. Export growth may continue to outpace import growth in 2015, but just to maintain its existing share of GDP, external surpluses would need to rise by over $90 billion this year. International resistance to such an external imbalance will be strong. Expecting trade to be a plus factor in 2015 GDP growth is unrealistic. We foresee net export growth as at least slightly negative in 2015; we speculate, with a heavy dose of subjectivity, a -0.1% contribution to 2015 GDP.

The most predictable source of China’s GDP growth is household consumption, which has grown at 8-12% a year in real terms for most of the past two decades. Business investment changes with the economic cycle and foreign demand can be volatile, but household income growth and the resulting consumption have progressed fairly evenly, though at an average below investment – hence the oft discussed problems of rebalancing. We expect this expansion pattern to continue, with nominal household consumption growth of 10.7% in 2015, adding RMB 2.5 trillion in new marginal demand on top of 2014 numbers. Government consumption expenditures have grown increasingly in line with household consumption in recent years, as a greater share of outlays are transfers to the household sector – such as education and healthcare – rather than subsidies for industry. We project 10.7% growth in government consumption for 2015 as well – the same as we use for households. This translates into RMB 960 billion in new government consumption this year, on top of the RMB 9 trillion 2014 base. Combined growth in government and household consumption activity in 2015 should amount to RMB 3.5 trillion in growth, for 3.9 points of GDP growth in 2015 – one-tenth of a point higher than 2014.

It comes down to money. Gross capital formation – or GCF, the measure of investment used in GDP – contributed a heady 4.2 points of the 7.7% growth China achieved in 2013, but only 2.8 points in 2014, as shown in Figure 1. With +3.9 point from consumption and -0.1 points from trade, as explained above, Beijing needs +3.2 points from investment growth to get to its likely 7% GDP growth target – about RMB 3 trillion higher than last year’s RMB 30.6 trillion in gross capital formation, according to our estimates. That comports with PBoC’s “neutral and moderate” (growth) formula. It means gross capital formation will expand slower than 2013, but faster than 2014; not so fast that reform is put on hold, and not as fast as consumption growth so we see continued rebalancing.

This is an expenditure growth story compatible with recent patterns, external realities, and Beijing’s stated priorities. It’s not the only scenario, but it’s currently the one we find most compelling. However, any number of problems could derail this plan. A deeper drop in exports would leave China resorting to even higher, unhealthy levels of investment growth; a further surge in net exports, conversely, could push growth above potential and interrupt reforms. Private reluctance to commit to the high-quality investment needed to boost GCF numbers would be offset with more government-directed lending that solves a short-term problem while exacerbating a longer-term imbroglio – a concern we turn to next.

The third relevant question about the 2015 growth outlook is what are the potential costs to achieving the stated target? While Beijing has the wherewithal to deliver 7% or more growth in 2015, doing so could impose a cost in terms of reform credibility and future debt. With limits on its ability to deliver household consumption and net exports to buoy China toward 7%, and government consumption budgets difficult to fine-tune in the short-term, Beijing will lean on investment growth to bridge any gaps. Part of that investment growth has, of course, been off-balance sheet government spending though local financing vehicles, which the central government has turned on and off as a short-term stimulus since 2007, piling up massive bad debt in the process. By opening up state-dominated sectors to greater private investment, Beijing will reduce the future costs entailed by bad lending in an effort to manipulate market outcomes. If Beijing is unwilling or unable to embrace greater market liberalization by carrying out deeper policy reforms, then it will inflate the costs incurred to deliver 7% growth.

Fourth and finally, there is one additional question that we didn’t expect to find ourselves asking until about a month ago: will China’s 2015 reported growth be true? For some time analysts have questioned Chinese GDP, in light of observable consumption of inputs like electricity. For years, real GDP growth and electricity consumption growth moved together at a ratio averaging 1 to 1 over the cycle. This has trended down in recent years; as of late 2014, industrial electricity consumption was growing at less than 3.8%, versus official GDP growth of 7.4%, leading some to speculate that the latter was overstated. But recall the rise of services and the struggle of heavier industries. In our view, 3.8% electricity consumption growth is fairly consistent with reported GDP growth given the rising weight of services.

That is not our reason for doubting the numbers. Rather, our concerns arise from Beijing’s decision not to upwardly revise China’s GDP estimate according to new information and best practice following the 2013 census, having previously committed to doing so. If Beijing were to have fully revised up existing GDP, the value of new marginal activity necessary to report a given rate of GDP growth would be even higher in the future. By keeping the base lower, a given rate of growth is easier to achieve. Further, if the revisions to the base are introduced slowly over the years to come, without clear explanation from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), it might appear as though GDP growth were higher than it is. The unusual machinations around the December 2014 release of the latest census results leave us no choice but to at least consider that possibility.

Conclusion

We expect reported 2015 GDP growth in the vicinity of 7%, with continued structural adjustment to the mix of activity that makes up the headline figure. The biggest risks to that outcome are on the upside, in the event that there is an over-deployment of stimulus, always a strong possibility in China, which would delay needed policy reforms in all likelihood. On the external side, we expect moderate recovery in investment growth to restore some hope to natural resource exporters, while aggressive efforts to maximize net exports (and the natural out-spilling of overcapacity goods) will fuel trade frictions with those competing with China’s exporters. To manage those tensions, Beijing’s trade diplomacy will turn more accommodating to help assuage frictions and hedge against loss of the foreign market access China needs now more than ever. The subject of China’s external economic policy priorities for 2015, and their connection to internal reforms is, however, a subject for a separate discussion.