Buying the Dip? China’s Outbound Investment in 2020

While COVID-19 weighed on Chinese outbound investment in 1Q 2020, many are concerned that market volatility may create fire sale opportunities for Chinese buyers. But is China really in a position to take advantage of low asset prices globally?

After two decades of double-digit growth, China’s outbound investment boom slowed after 2016 as policy tightened domestically and scrutiny overseas increased. By 2019 activity had fallen back to 2014 levels. While the COVID-19 outbreak further weighed on Chinese outbound investment in 1Q 2020, many governments are concerned that market volatility may create fire sale opportunities for Chinese buyers. But is China really in a position to take advantage of low asset prices globally? This note explores the Chinese outbound investment outlook at this critical juncture.

The key findings are:

- The virus outbreak brought China’s outbound investment to a halt in early 2020: Chinese outbound investment was already on a downward slope since 2016 and the draconian measures to fight the virus outbreak prevented deal making in the first quarter of the year, with only a few exceptions.

- Macro and domestic policy hurdles are larger than realized: Domestic macroeconomic headwinds and resulting capital controls were responsible for most of China’s outbound investment decline since 2016. COVID further aggravates these problems and China’s financial stability is even more at risk now.

- Global market volatility may create buying opportunities: Some Chinese firms are positioned to take advantage of the sharp drop in global company valuations. Just as in 2009-12, most such investment will be mostly profit-oriented and in no small part reflect bearish sentiment about China from investors eager to hedge their home-market exposure. How to filter out strategically concerning activity while permitting benign commercial investment remains a difficult question.

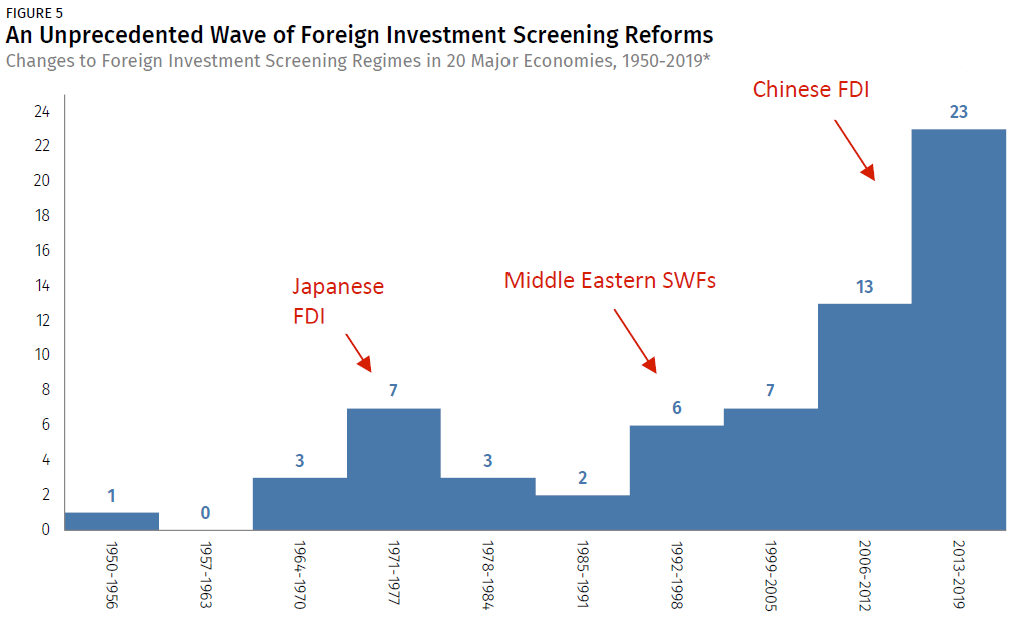

- China’s investors face tougher screening and regulation abroad: Many OECD countries have overhauled their investment screening regimes over the past decade, giving regulators power to block deals that raise national security concerns or otherwise run afoul of national interests. Some governments are contemplating special rules to protect companies from foreign buyers for industrial policy reasons.

- Any acquisitions from China are at high risk of politicization: Aside from formal regulatory scrutiny, virtually any high-profile acquisitions will likely be viewed as predatory under the current circumstances, given the Chinese origin of the COVID pandemic, risking public backlash and drawing in political intervention.

China’s Outbound Investment Trajectory: Rising High, Falling Deep

China was not a major player in global investment until the mid-2000s. Driven by policy loosening by Beijing and favourable global conditions, its outbound FDI (OFDI) grew from next to nothing to an average of almost $50 billion per year in the late 2000s. Easy money and loosening of Chinese policy in 2014 boosted flows to more than $200 billion in 2016, eliciting both enthusiasm about fresh capital and anxiety about economic and security risks.

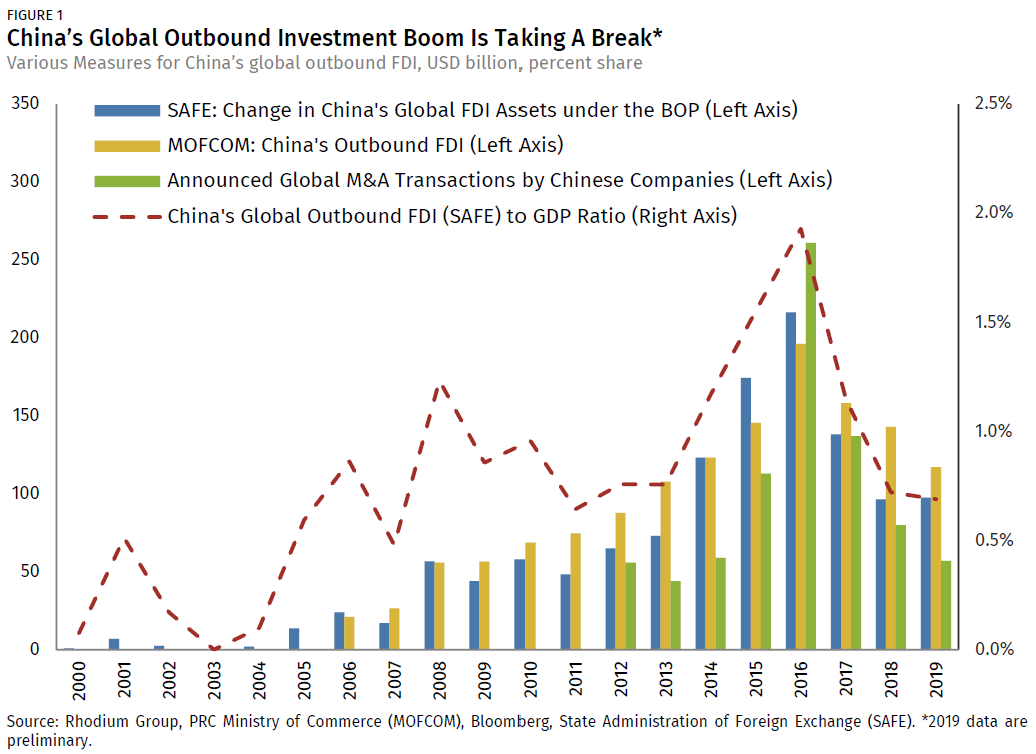

Since 2016 China’s outbound investment has been on a downward trajectory. Outflows dropped precipitously in 2017 and 2018 after Beijing restricted “irrational” outflows. In addition to domestic regulators, Chinese investors also were confronted with greater regulatory and political scrutiny abroad, as economies tightened investment screening regimes due to concerns about China’s compatibility with their democratic market economies. This slowdown is visible across all available data sources (Figure 1) and has changed the narrative of the inevitable rise of China as a global investor.

In 2019 this downward trajectory continued with China’s global OFDI dropping back to 2014 levels. Official Chinese statistics show a modest decline in outbound FDI for the year: MOFCOM reports outbound FDI at $117 billion for January-December 2019, a decrease of 9.8% from the same period in 2018 in dollar terms. The global M&A component shows a deep drop, with newly announced 2019 deals at $50 billion, versus $80 billion in 2018, amounting to the lowest level in eight years.

The Impact of Covid-19: Roadblock or Catalyst?

The COVID-19 pandemic is disrupting the global economy, with implications for cross-border investment flows in the short and long run.

China was the origin of the outbreak and the first country to be hit economically, with a big negative impact on deal-making. Domestically, the level of M&A transactions has slowed sharply: total announced deal volume dropped by more than half in 1Q 2020 compared to previous years. On outbound investment, preliminary transaction data and anecdotal data points indicate that 1Q 2020 will show the lowest volume of new deals from China in almost ten years.

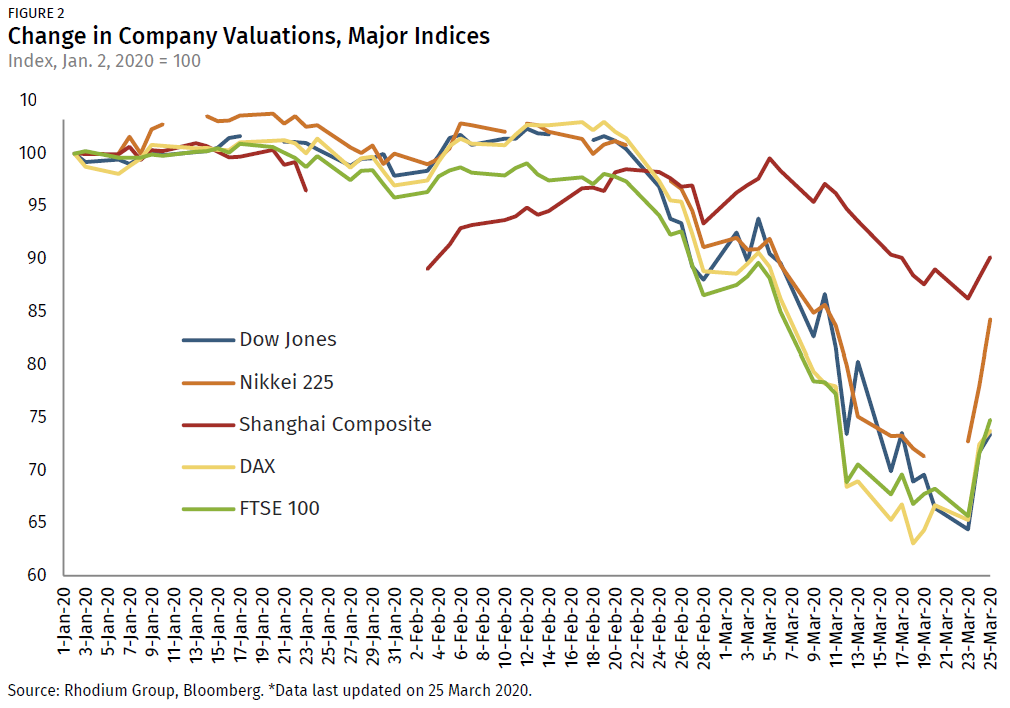

As the economy is gradually heats back up, we will see recovery of outbound investment activity in 2Q/3Q 2020 from this low base. The question is: how much upside is there, given the rapidly changing situation in global markets? As the virus spread markets plummeted, with equity markets around the world down by double digits. US equities were down 36% at the trough (so far), and German stocks lost 37% and Japan’s Nikkei 225 was down 29% at the lowest point so far (Figure 2).

After the 2008-09 crisis Chinese firms ventured out to acquire discounted assets around the globe, especially those with strategic utility: iron and nickel ore, oil, and myriad other commodities that China became dependent on. With China’s economy having a head start coming out of the present crisis and its appetite for technology and other strategic assets as strong as ever, will history repeat itself?

Domestic Variables: Macro and Policy Hurdles Will Persist

The most important variables for China’s 2020 outbound investment outlook are the same policies that were steering down OFDI since 2016: tighter administrative controls of outbound capital flows; a crackdown on “irrational” outbound investors; and a broader campaign to reduce leverage in the domestic economy.

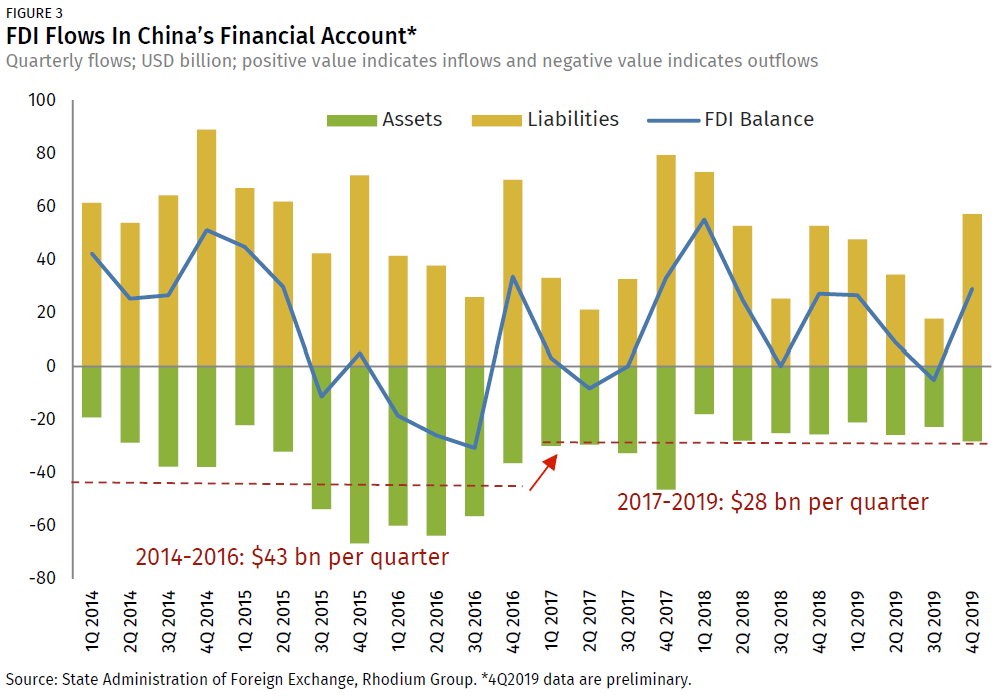

In response to large-scale capital outflows and a widening financial account deficit Beijing tightened its grip on outbound investors to squeeze out “irrational” outbound flows in late 2016, first informally through an internal State Council directive and then formally in mid-2017 through new regulations including a blacklist for certain sectors. These steps correlated with a sharp downturn in outbound M&A since late 2016. China’s balance of payments data show that these rules have effectively curtailed outbound FDI flows: for the period 2014-16 China recorded an average of $43 billion of FDI outflows; after capital controls were imposed, outflows became less volatile quarter-over-quarter and instead stayed within a close range, averaging $28 billion per quarter (Figure 3).

Parallel to these broader controls Beijing went after specific individual companies perceived to be investing “irrationally”. The highest profile example was Anbang, which was taken over by China’s insurance regulator, its overseas assets sold and its founder and chairman Wu Xiaohui sentenced to prison for fraud and embezzlement. In 2017, China’s banking regulator instructed local banks to conduct financial reviews on firms including Anbang, HNA (which was taken over by the Hainan provincial government in February 2020), Wanda, Fosun, and Zhejiang Rossoneri Sport Investment (the former owner of AC Milan). In addition to going after individual firms, Beijing also issued new rules to improve risk management for outbound investors, including releasing a new OFDI approvals and registrations measure in 2018 and extending the social credit system to cover outbound investors.

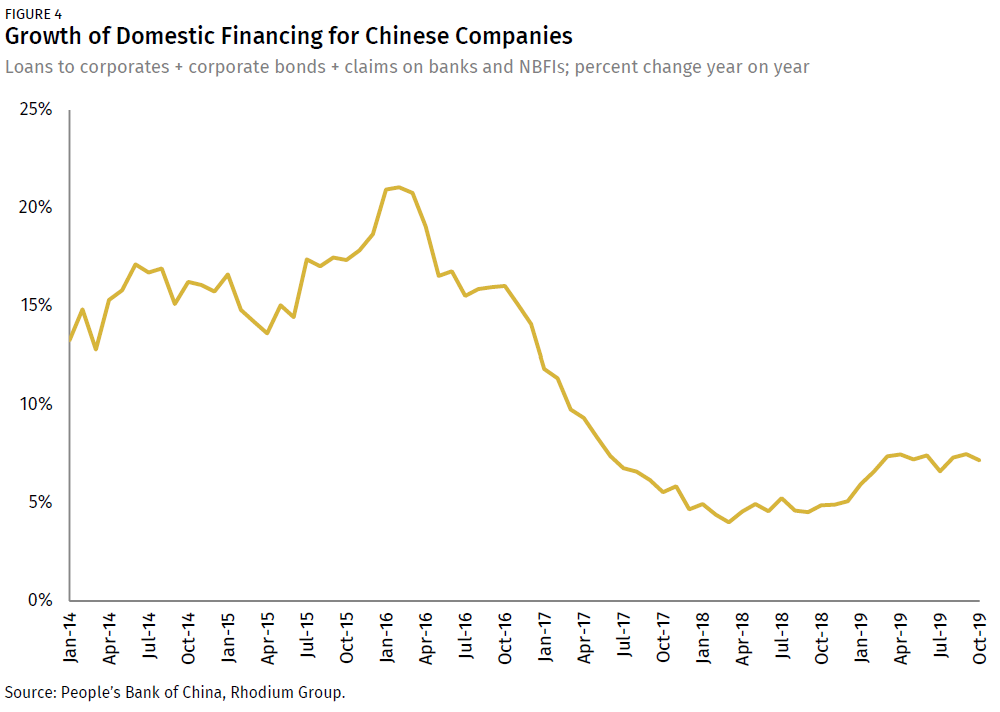

A crack down on excess leverage in the domestic economy further amplified the headwinds for outbound investors. Starting in 2016, China launched a deleveraging campaign to curb excessive borrowing, including reining in shadowing banking and tightening money supply in order to clean up systemic risks. Figure 4 shows how this deleveraging campaign reduced growth of available onshore financing from more than 15% from 2014-2016 to low single digits in 2018. This tightening of liquidity took an immediate toll on highly-leveraged outbound investors (where the banking regulators ordered loan checks on the specific investors mentioned above) and weighed on the financing abilities of Chinese companies reliant on onshore capital.

These conditions and policy measures persist in 2020. China’s room for a monetary response to the COVID-19 crisis is limited and its stimulus program will not be as aggressive as in the aftermath of the 2008-09 crisis (see our note from March 24). Likewise, the external situation remains volatile. Lower commodity prices and lower outbound tourism spending add to the current account position, creating room for outflows through the financial account. However, the spread of the virus globally will hurt external demand, dragging down Chinese exports. China’s currency remains under depreciation pressure as households and companies remain eager to move money offshore. This is evident in persistent and high unexplained outflows through the net errors and omissions account. These factors prevent Beijing from taking the permissive stance on outflows that prevailed during the boom years up to 2016.

Overseas Attitudes Toward Chinese Capital: More Restrictive

In addition to domestic variables, Chinese firms face a different international environment compared to 2008-09.

One difference is that governments in most advanced economies have been swift and aggressive in responding to the present financial crisis, providing relief to the banking system and emergency funds to the most impacted sectors. The US Federal Reserve cut its target for the federal funds rate to near 0 percent and pledged limitless asset purchases. On March 25, Senate and the White House came to an agreement on a $2 trillion stimulus package to help stabilize the US economy. Similarly, in Europe the ECB announced a EUR 750 billion asset purchase program in order to help mitigate the impact of the coronavirus outbreak, and many national governments are implementing fiscal stimulus programs and measures to stabilize struggling firms. While companies will undoubtedly remain under deep financial pressure in coming months, there is less pressure for most firms to find “White Knight” investors to save them from going under.

Long before the current emergency, many nations had begun to beef up their toolsets for identifying and preempting foreign acquisitions of sensitive assets. The past ten years have witnessed a wave of government regime building to screen and block foreign takeovers for national security, public order interests, and even the market structure of industry ecosystems considered critical (Figure 5). This trend was driven by the emergence of China in combination with technological progress that has blurred the lines between civil and military use technologies and created greater vulnerabilities from foreign ownership of critical infrastructure and data.

Aside from narrow national security considerations, governments will likely expand their scrutiny to include a broader set of economic and societal considerations in such times of crisis. Some countries – for example Australia or Canada – already have explicit provisions in their laws that allows government to consider the “net economic benefit” or the “national interest” when screening foreign investment. Others have made clear that they intend to step in and take extraordinary measures to protect local companies from foreign takeovers in the aftermath of COVID-19. The European Commission issued guidelines to ensure strong EU-wide investment screening to “protect critical European assets and technology” during the coronavirus crisis. German government officials stated that they will take measures to “avoid a sell-out of German economic and industrial concerns”, including state financial support or participations in takeovers.

Finally, in the current environment, any high-profile Chinese acquisition runs a high risk of turning into a public relations disaster for the parties, and for China. There is a long history of politicization of Chinese deals and it is hard to imagine politicians and special interest groups not aggressively spinning any major transaction as “predatory”. Beijing is aware of this risk and would likely lean in to prevent such outcomes through its outbound approval process.

Conclusions

Chinese outbound investment was already in decline since 2016, and the COVID-19 outbreak crippled deal making in 1Q 2020. We will likely see a recovery of outbound activity for the remainder of the year just from “low base” effects, as the economy recovers and investors decide to bolster existing overseas operations or seize new opportunities created by market volatility.

Persistent domestic policy restrictions and macro conditions as well as scrutiny abroad make a return to the outbound investment bonanza of 2015/2016 unlikely. However, certain Chinese investors will step up in coming months, especially large private firms with relatively stable revenue streams and access to offshore capital, and state-related firms and funds with an explicit mandate to invest in strategic assets including high tech, commodities and infrastructure. Under current circumstances it is most likely that Chinese buyers will target small and medium-sized technology firms in countries with less robust screening systems and relatively friendly relations with China.

Investors see crises as times of opportunity and are scanning the market for targets. Mergers and acquisitions are a necessary element of restructuring and recovery in any financial emergency, and they will be in 2020 as well. As during previous crises, political leaders will face the challenge of defending openness to foreign capital and safeguarding national security and other national interests. In today’s environment of mistrust and misalignment, investment from China will pose particular challenges for policymakers, who will need to carefully disentangle commercial endeavors from strategic gambits that might tilt the geopolitical balance after the virus has been tamed.