Credibility in the Balance

The credibility of government guarantees to support a wide range of China’s financial assets and companies is hanging in the balance as corporate bond defaults rise.

China’s financial markets have been spooked by a rise in corporate bond defaults, which are undermining faith in the implicit guarantees investors have come to expect from state-owned enterprises and local governments. China’s central bank has sent investors indirect messages that they must manage credit risks on their own, even as the PBOC has provided some short-term liquidity to the banking system.

Our 2018 report Credit and Credibility highlighted the dilemma for authorities in Beijing. The widespread belief in government guarantees has acted as a bulwark against financial crisis even as China embarked on an unprecedented decade-long credit expansion. Proper financial reform, however, requires the authorities to rein in expectations that they will always be there in times of financial stress. But addressing this moral hazard issue entails significant risks. Facing novel financial risks, no one can be sure when markets are pricing new credit risks appropriately, or potentially starting a larger asset liquidation cycle with systemic implications. The credibility of government guarantees to support a wide range of China’s financial assets and companies is hanging in the balance.

A New Era for Government Credibility

Around a decade ago, a Chinese government economist described to me, in very blunt terms, the dilemma authorities faced in tackling China’s pervasive moral hazard problem tied to local government debt. Allowing local governments to default on debt issued by their financing vehicles (LGFVs) was necessary, of course, to prevent the debt load from growing too large. But permitting a token default or two would not be enough: markets would see this as a one-off. To truly address the moral hazard problem you would need to create real instability in the market, with investors suffering meaningful financial losses. In China’s system, he explained, such losses carried political consequences. People would think that the government had cheated them, by guaranteeing the assets and then backing away. For over a decade, markets have been living with this ambiguity. There has been no real effort to clarify where government guarantees begin and end. And the fact that Beijing always stepped in to stabilize financial markets when signs of stress arose, reinforced the perception that a government obsessed with political stability would ultimately step in.

Those market perceptions are now changing. The shift has been gradual. Back in 2018, signs emerged that peer-to-peer lending products were not going to receive bailouts from Beijing. Then, in May 2019, the shocking default of Baoshang Bank reinforced the idea that even financial institutions themselves would be allowed to fail. But over the past three weeks, bonds issued by companies backed by local governments as well as state-owned enterprises are coming into play. We have seen Brilliance Auto, Tsinghua Unigroup, and Yongcheng Coal default on their corporate bonds. Credit ratings have meant very little as even AAA-rated companies have begun to default more frequently. Doubts are now being raised about the financial information provided by these companies. Some appeared to have enough cash on hand to repay their maturing debt, before suddenly defaulting.

In China’s financial markets, the credibility of local government guarantees is being questioned. Investors are wondering how local governments will manage the assets of local firms facing financial difficulty—will they attempt to negotiate with bond investors or will they protect the firms’ best assets and simply default on the debt? Local and provincial authorities have taken very different approaches so far, and markets are starting to consider the fact that local governments’ actions may represent risks that need to be priced, rather than sources of support.

Bond investors also seem to be evaluating the creditworthiness of local governments themselves, assessing fiscal conditions, GDP growth, and prospects for land sales, rather than the financial conditions of the companies issuing bonds. Even solid firms within riskier localities may suddenly find themselves cut off from financing. This is highly unusual in China’s financial markets.

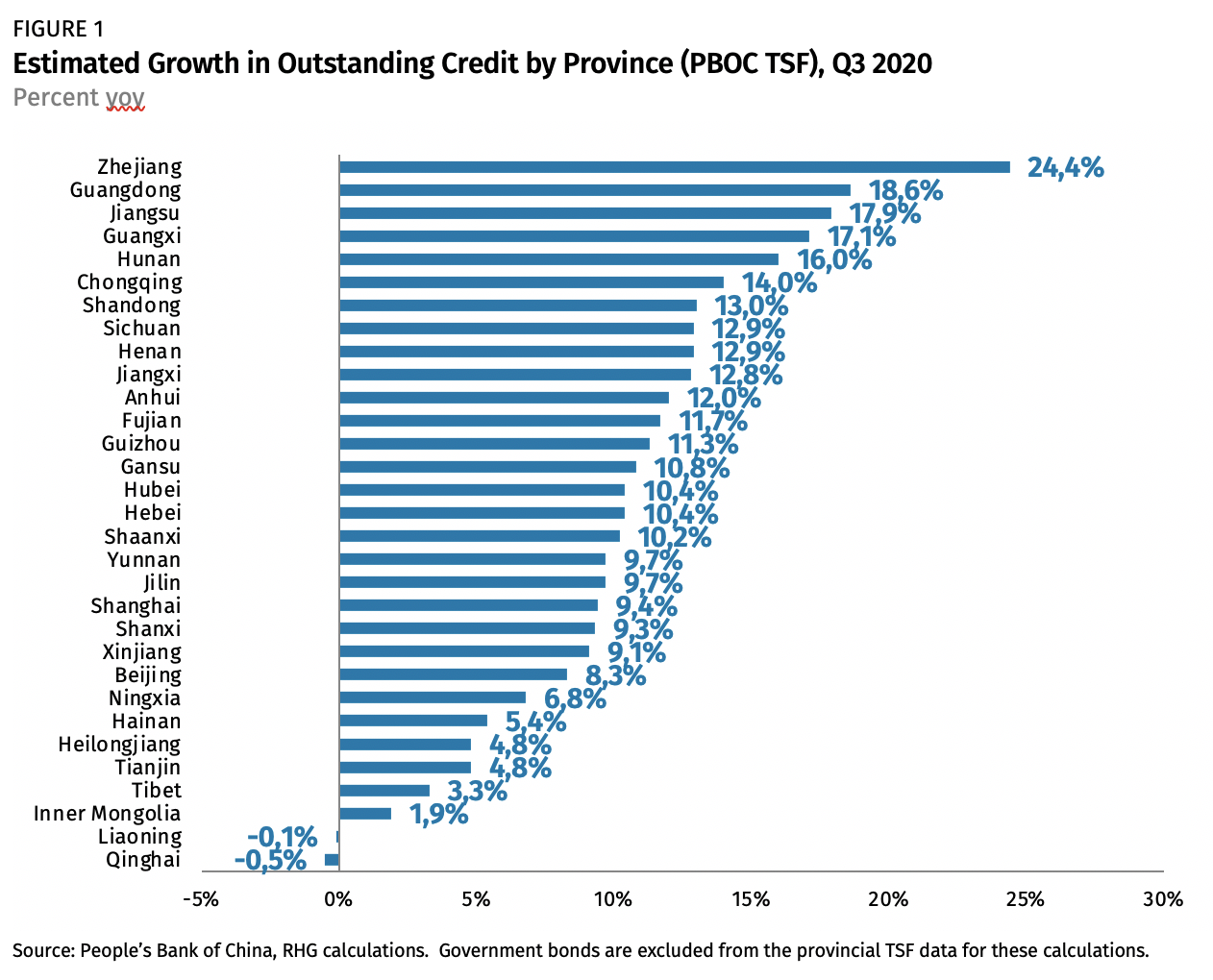

As a result, the variance in credit conditions across Chinese provinces has never been greater than in 2020. Developed provinces on the coast are receiving the lion’s share of new credit this year. Interior and northeastern provinces are seeing much lower growth rates, or even occasional credit contractions.

We have referred to this phenomenon as “geographic counterparty risk”, a form of credit risk specific to China’s political system, because of the importance of local government guarantees for the creditworthiness of local state-owned enterprises, property developers, local government financing vehicles, and other firms. In our recent report, The China Economic Risk Matrix, we discuss these risks extensively in Chapter 6, exploring the possibility that diminished local government credibility in one area could hamstring entire local economies. There is also a risk, if Beijing is slow to react, that problems in one locality could trigger contractions of credit in others.

Beijing’s Dilemma in Balancing Risk and Stability

We discussed the tradeoffs for authorities in managing these types of risks in Credit and Credibility. Beijing can step in and offer central government guarantees if systemic risks build. But financial regulators probably want to see market players manage these new credit risks on their own, without expecting a strong government response. This seems to be the signal that the PBOC itself is sending. This week, the central bank has made no direct statements, but the bank’s WeChat account circulated a speech from Governor Yi Gang from earlier this year, in which Yi emphasizes that bond investors should manage their own risks, while implicit guarantees should end. Yi argued in the speech, “Government bonds, policy bank bonds and central bank paper can be considered risk-free assets for bondholders, where the risk will be assumed by the government. Beyond those, all other bonds’ risks should be absorbed by bondholders.” The signal to the market was clear.

The problem for authorities is that the declining credibility of local governments is an entirely new form of financial risk, and the market is now struggling to price it. Contagion is spreading and more firms are having their creditworthiness questioned. In the meantime, banks are tightening collateral standards for lending against corporate bonds, according to Bloomberg. Although authorities want market discipline for riskier firms, they cannot know how much credit risk might create broader contagion. No one can know this line clearly, given that there is no precedent for this risk in China’s financial system.

This Is Not Beijing’s First Rodeo

China’s financial regulators are no strangers to this dilemma. But their track record suggests that tough talk from the PBOC will eventually give way to emergency measures to calm financial markets when tensions run too high. In June 2013, the PBOC attempted to force banks to rein in their reliance on wealth management products for financing and lending to shadow financial institutions. It withheld short-term funding during a period when China’s interbank market was facing capital outflows and seasonal liquidity pressure. Markets reacted quickly, and overnight interbank financing rates shot up to 20-30%. The PBOC relented quickly, which reinforced market expectations that, when push comes to shove, the authorities will step in to maintain stability.

In May 2019, the sudden default of Baoshang Bank was accompanied by a PBOC decision to impose haircuts on the bank’s corporate and interbank depositors. The prospect of losses on these deposits caused many banks to suddenly lose access to funding in the market for interbank negotiable certificates of deposit (NCDs). The PBOC was then forced to step in and guarantee the interbank liabilities of the Bank of Jinzhou through credit risk mitigation warrants, a highly unusual step. When the Bank of Jinzhou and Hengfeng Bank were eventually restructured, no haircuts on interbank or corporate depositors were announced. China’s financial technocrats had set out to tackle part of the moral hazard problem in the banking system, only to relent when financial market contagion began to spread.

As we argued in Credit and Credibility, a financial crisis in China is more likely to occur when Beijing’s credibility is called into question, not when the country is hit by an external shock like the COVID-19 outbreak. It is more likely to arise from an attempt to reform the system, in which government guarantees are deliberately weakened, and market participants suddenly reassess prices across a broad range of assets. The credibility of government guarantees has been the most important bulwark against crisis so far. Now we are seeing signs that this credibility is eroding.

Beijing policymakers are now turning their attention to how to manage financial losses and potential losses, and how to allocate these losses within the system. Last weekend, in its annual financial stability report, the central bank provided a roadmap for responding to losses at distressed financial institutions. It sketched out a plan under which shareholders and investors in unsecured debt would incur the first losses. In a next step, local governments would try to repay creditors using their own resources. Then deposit insurance would come into play. Only after those avenues were exhausted would the central bank exercise its role as lender of last resort.

In the near term, the PBOC is likely to provide short-term funding to the interbank market when necessary, as it tries to keep financial markets functioning without explicitly reinforcing government guarantees for distressed state-owned enterprises and local governments. In the longer term, however, it is unclear how much stress among firms tied to local governments might be necessary to force Beijing to change course and provide guarantees.

One key distinction between previous cases and the present is that most of the current stress is being felt by corporate borrowers and bond investors, which are primarily non-bank financial institutions, rather than banks. As a result, the PBOC can allow more credit risk to materialize without worrying about the implications for the stability of the banking system itself. There are many steps between where we are now and a scenario of broader market contagion or crisis. But the pace of corporate bond defaults, the market reaction, and the implications for the credibility of government guarantees will need to be watched closely.