What to Expect from China’s New Five-Year Plan

Beijing’s upcoming Communist Party conclave will discuss the 14th Five-Year Plan, covering economic targets for the first half of the next decade.

Beijing’s upcoming Communist Party conclave will discuss the 14th Five-Year Plan, covering economic targets for the first half of the next decade. The meeting comes amid geopolitical and economic uncertainty, with China’s economy bouncing back from the shock of COVID-19 but facing a far more challenging external environment and threats of decoupling in high-technology industries. There will be few details in the statement issued immediately after the meeting, but a more detailed document with policy guidelines is likely be released in the following week. We see the following elements as the most important to watch:

The presence or absence of a longer-term GDP target. These targets have always featured in past Five-Year Plans, but the days of China doubling GDP every decade are in the past, and Beijing may gain policy flexibility by eliminating a target.

Details on how China plans to implement its “dual circulation” strategy. This could include measures to support domestic consumption and changes to technology and industrial policy goals in the face of a more hostile external environment. Whether the strategy is primarily focused on import substitution in high-tech supply chains or a more conventional consumer-focused stimulus for domestic demand will influence global views of this new policy element.

Environmental and energy policy changes that support Beijing’s recent pledge of carbon neutrality by 2060. The focus will be on whether Beijing adjusts near-term fossil fuel utilization and greenhouse gas emission targets, and sends signals about broader changes to energy policy.

National Policy Blueprint

The Communist Party of China (CPC) will convene the Fifth Plenum of its 19th Party Congress from October 26 to 29. The primary agenda item for the fifth plenary session is China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP). A Five-Year Plan is, simply stated, a top-level national blueprint for a wide range of policy goals—primarily economic and social, but also touching on defense and government organization. China rolled out its first FYP in 1953, and with the exception of 1963-1965, Beijing has continued to publish a new plan every five years. The 14th FYP will set a policy road map for the 2021-2025 period, and the statement released after the Fifth Plenum meeting next week should summarize the Party’s overall policy guidance. Following the statement, there should be a more comprehensive guideline document released in the first week of November providing additional details on key priorities in the plan. However, full details of the 14th FYP will not become public until March 2021.

Originally a Soviet industrial planning tool, a national FYP is only the beginning of a five-year policy planning cycle. After the central government ratifies the FYP, provincial governments will issue their own five-year programs for regional development, which will mirror the national FYP but be tailored to regional conditions. Then ministries and government agencies responsible for meeting certain targets of the FYP will announce their own plans for implementation. The 13th FYP released in 2016 contained 25 targets: twelve were “indicative” with implementation more flexible (such as GDP, urbanization, internet coverage) and thirteen were “binding” and rigidly enforced (such as poverty reduction, shantytown reconstruction, air quality improvement).

A FYP is often supported by separate economic initiatives. Recent examples include Made in China 2025 (MiC2025) and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), both of which were designed separately but incorporated into the 13th FYP unveiled in late 2015. Official fanfare is usually attached as well—in 2015 the government sponsored a catchy music video in English (The 13 What), to introduce the otherwise tedious policy document to international audiences.

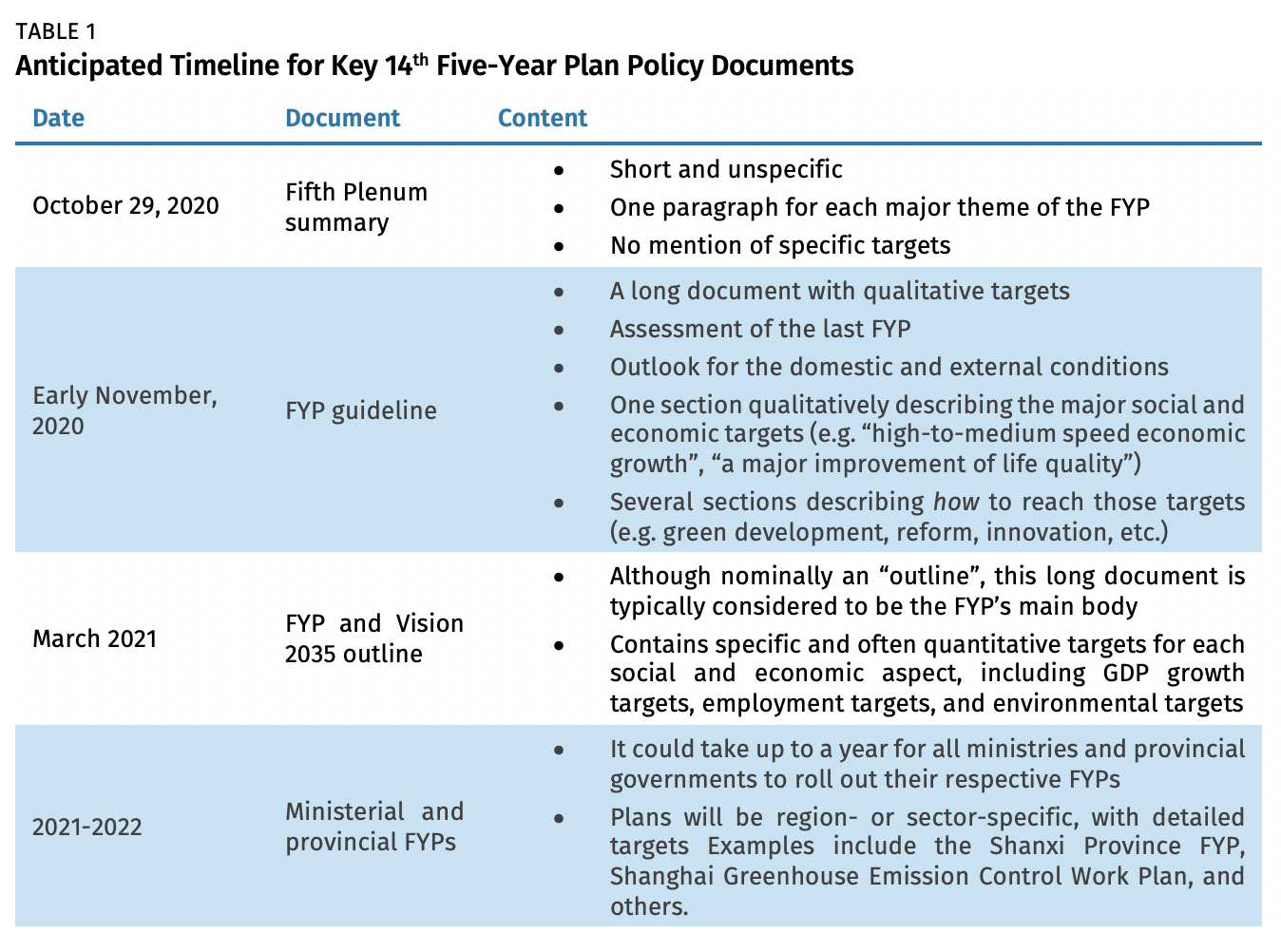

In terms of the specific timeline for the release of policy documents related to the plan, here is what we expect to happen in the coming months (Table 1):

A special feature of the upcoming 14th FYP cycle is that a “Vision 2035” Plan will also be announced. Vision 2035 is a longer-horizon strategy, which may overlap with the current 14th FYP in its focus of near-term priorities, but could also set the tone for future FYPs through 2035. These 15-year plans are formulated on an irregular schedule and tend to reflect political narratives rather than prescribe concrete economic goals. The CPC 19th Congress in 2017 laid out two “centenary goals”. The first is to “completely finish building a moderately affluent society” by 2020 (2021 is the CPC centennial), and we would expect China’s leadership to declare victory in achieving this objective this year. The second centenary goal is to make China a “modern socialist great power” by 2050 (2049 is the centennial of the People’s Republic). Although the plan has more political than economic significance, it might contain some implied economic targets, such as a goal of doubling GDP by 2035 from the 2020 level.

Easier to Work Without Firm Growth Targets

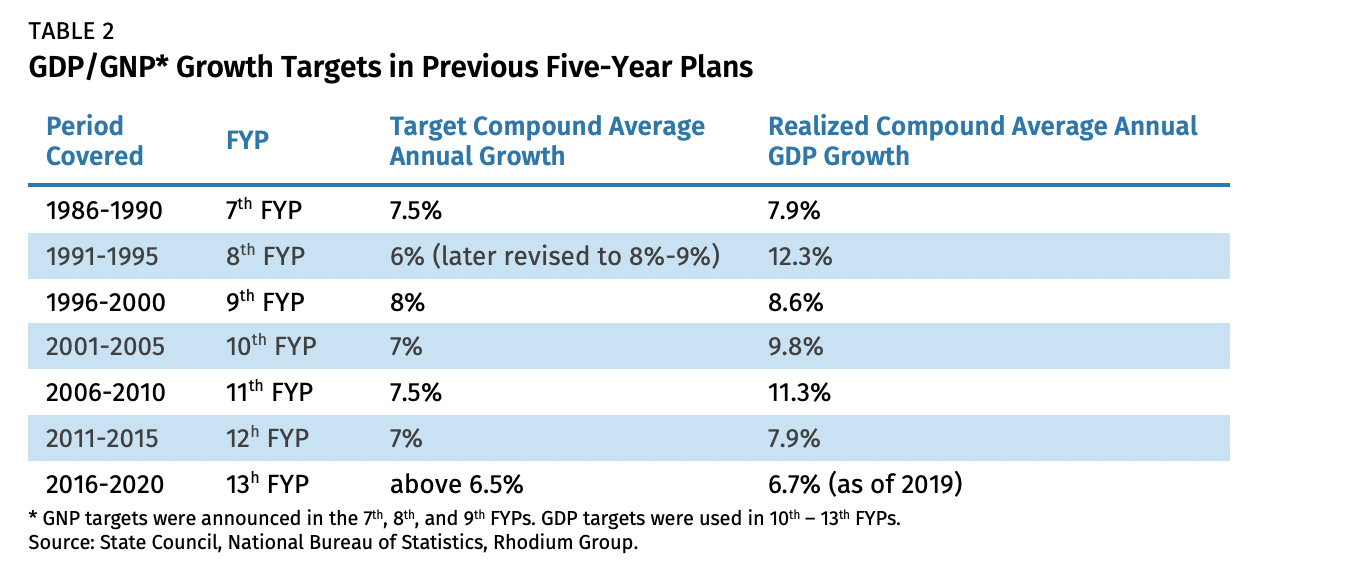

Five-Year Plans have always included numerical growth targets for multiple indicators. In the planned economy era, an overwhelming list of targets would cover almost every aspect of economic activity: how many steel plants to build, how much energy to consume, how much in taxes to collect, and sometimes how much the population should grow. Starting from the Seventh FYP (1986-1990), the new GNP/GDP accounting concept, which at the time was relatively new in China, became the single most important economic target within the FYP. There is nothing magical or scientific behind past growth targets, which were typically in the 6%-8% range for annual growth, and consistently turned out to be underestimates (Table 2). One explanation for these targets is that it is easier to publicly communicate a more tangible goal of GDP “doubling in ten years” (originally inspired by Japan’s “Income Doubling Program” in the 1960s) than to provide concrete annual targets, as doubling GDP in a decade mathematically translates to 7.2% growth per year.

However, the narrative of GDP doubling every decade might have finally run its course. China’s growth has come in below 7% every year since 2016, and it suffered a large setback during the COVID-19 shock this year. This year, Beijing may reach for a 15-year doubling of GDP (4.7% per year), since China’s long-run growth potential has clearly declined.

But Beijing is not required to set a GDP target at all, and may be better off without one. These types of political ornaments only introduce constraints in managing the economy, as headline growth targets tend to discourage honest economic data reporting (See Aug 2019, “China’s GDP: The Costs of Omerta.”) Keeping a long-term GDP target out of the FYP for the first time in 35 years would send a positive signal that, going forward, markets rather than politicians will play a more decisive role in resource allocation—even though this message would still be delivered as part of a central planning exercise.

If Beijing does leave a GDP target out of the 14th FYP, it will be important to watch the plan’s wording concerning the desired speed of economic growth, which will likely shape China’s policy bias. In the 13th FYP, Beijing still targeted “medium to high-speed” growth, but there is a reasonable chance that “high” will be dropped in the upcoming plan.

A First Look at “Dual Circulation”

One of the most important elements coming out of the Fifth Plenum will be the interpretation of Beijing’s “dual circulation” strategy in the FYP (see Aug 5, “Understanding ‘Internal Circulation’”). The key questions raised by the policy concern how China plans to stimulate domestic demand and production (“internal circulation”), and the balance of policy emphasis between maintaining an export-oriented economy with foreign technology and investment inputs (“external circulation”) and focusing on domestic demand-driven growth. China’s recent post-COVID rebound has received strong support from external demand, while domestic consumption indicators have been slower to return to trend levels.

Supporting Household Consumption

So far, China’s post-COVID stimulus efforts have focused primarily on industrial production and extending terms of bank credit for enterprises, rather than maintaining employment and boosting household incomes. At the same time, China’s personal income tax collection is very low (just over 1% of GDP), so more traditional countercyclical policies to boost consumption are unlikely to be very effective. Consumption coupon programs have been attempted in the past, particularly in the auto sector, but generally have the effect of pulling demand forward and distorting inventory cycles. Any initiatives to provide additional support to the domestic consumer within the 14th FYP will be closely watched. One long-awaited potential reform would be encouraging additional land market liberalization, which could help to boost rural household incomes if these rural residents were allowed to rent out or sell their land to generate income (See our Dashboard analysis of progress in this area).

The Party’s declared assessment of the external environment will offer valuable clues on the degree of China’s intended internal shift. In past plenum readouts, the country was often described as being “still in the period of strategic opportunity”. This suggested optimism about the external environment, signalling support for China’s engagement with the global economy. However, in recent months the tone of high-level political messages started to shift to caution and vigilance, with the Politburo’s July meeting statement that “the world is in the middle of a once-in-a-hundred-years sea change” just one example. A pessimistic assessment of the global environment would be expected to lead to measures to increase China’s self-reliance.

Industrial Policy

A crucial aspect of “dual circulation” is industrial policy. China’s FYPs, by definition, always designate priorities to develop certain sectors. But they do not necessarily drive substantial industrial policy programs, which we narrowly define as policy measures that aim to stimulate investment and growth within specific sectors. The number of China’s industrial policy programs remained low before the 2000s, covering a narrow range of industries. After the mid-2000s, however, China’s industrial policy programs began to surge and expand. A milestone was the 12th FYP (2011-2015), which identified seven “strategic emerging industries” as development priorities. These included energy-saving and environmental protection, next generation information technology, biotechnology, advanced equipment manufacturing, new energy, new materials, and new energy vehicles, with digital innovation added to the list in 2017. This central guidance later spurred a total of 21 ministerial FYPs for sector-specific development—indicating real implementation of industrial policy plans.

Especially controversial in China’s industrial policy approach within recent FYPs have been the use of explicit quantitative targets. For example, the 13th FYP (2016-2020) decreed that strategic emerging industries should account for 8 percent of GDP by 2015 and 15 percent by 2020. Made in China 2025 (MiC2025), which was a key part of the 13th FYP, designated market share targets for a list of 10 priority industries. This generated a broader international backlash amid fears that China would ultimately close its markets to foreign competition in these industries.

Beijing faces a difficult choice. On the one hand, an increasingly hostile external environment is inviting an approach that doubles down on industrial policy—building backup production capacities, covering supply chain vulnerabilities, and breaking foreign technology blockades. On the other hand, Beijing likely understands that the “wish list” of industries it is trying to promote in the FYP could easily be used as a US “hit list”, further restricting exports of components critical to those industries. The US Section 301 Investigation in 2018 cited several programs from the 13thFYP, such as MiC2025 and Military Civil Fusion, as evidence of China’s distortive policies. Chinese officials have since stopped publicly discussing the controversial MiC2025 program altogether. Beijing has also quietly removed public promotion of the Thousand Talents Program, which has generated accusations of espionage and technology theft.

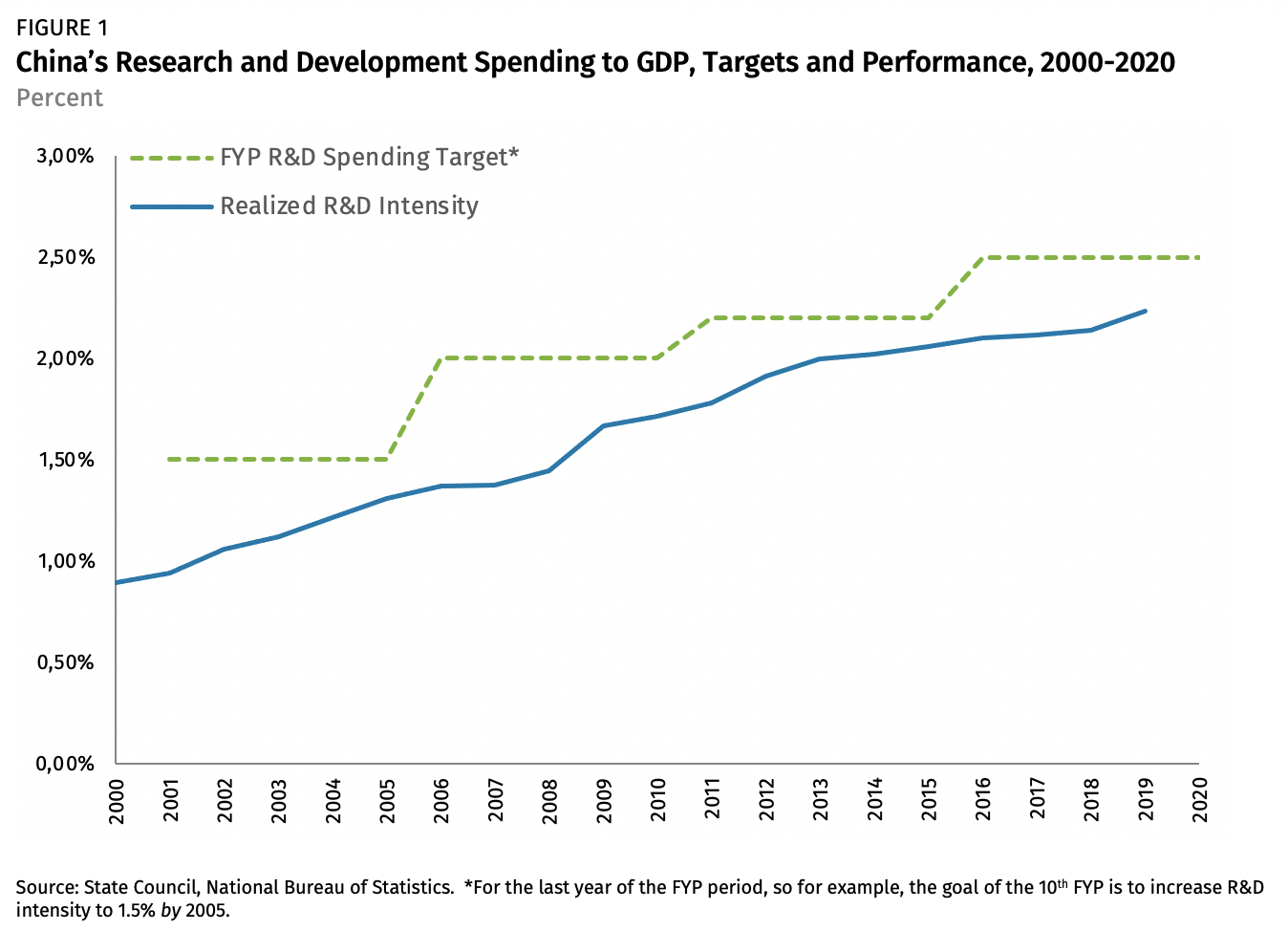

It is quite likely that the upcoming Five-Year Plan will allocate more resources to domestic research and development (R&D) and attempt institutional reforms of the domestic R&D system. The proportion of R&D spending within the economy was one of the few areas where China fell short of its FYP targets (Figure 1). Spending more on domestic R&D is consistent with the dual circulation narrative while not being externally controversial. In 2020, the leadership has repeatedly emphasized the importance of innovation, and the government rolled out a few reform programs that aim to revamp the R&D system, with measures such as offering bigger financial incentives to researchers, and better protection for intellectual property. The R&D section of the 14th FYP is likely to be closely connected to the National Medium and Long-term Science and Technology Development Outline 2021-2035, which is expected to be released in early 2021. This 15-year strategic technology roadmap will shed more light on what foundational technology bottlenecks China plans to break first (and how). China’s technology policy planning and industrial policy planning are often mutually reinforcing.

At the same time, China will also be motivated to modify its industrial policy approach—avoiding specific market share targets and stepping back from targeting too many sensitive industrial subsectors under one policy program. A differentiation of urgency is necessary—for sectors that are already under US blockades (such as semiconductors), China is likely to double down and strengthen government support. But for other sectors, Beijing will have to think hard before committing to an overt industrial policy strategy.

Looking for “Green” Shoots

China’s recent pledge to be “carbon-neutral before 2060” was somewhat surprising, and European observers in particular will be watching the FYP to see if Beijing provides additional details on progress toward this goal. The pledge appears to have been driven in part by geopolitical considerations. The EU had been pressing Beijing to commit to new climate targets and by doing so, Chinese leaders may have hoped to ease growing tensions in the relationship and reduce the chances of a transatlantic front developing against Beijing under a possible new US administration. But without a detailed roadmap for achieving carbon neutrality it will be difficult for Beijing to persuade European and American skeptics of its good intentions. Observers will be looking for “green” shoots in the upcoming FYP—mentions of near-term fossil fuel utilization targets, greenhouse gas emission goals, and general changes in energy policy.

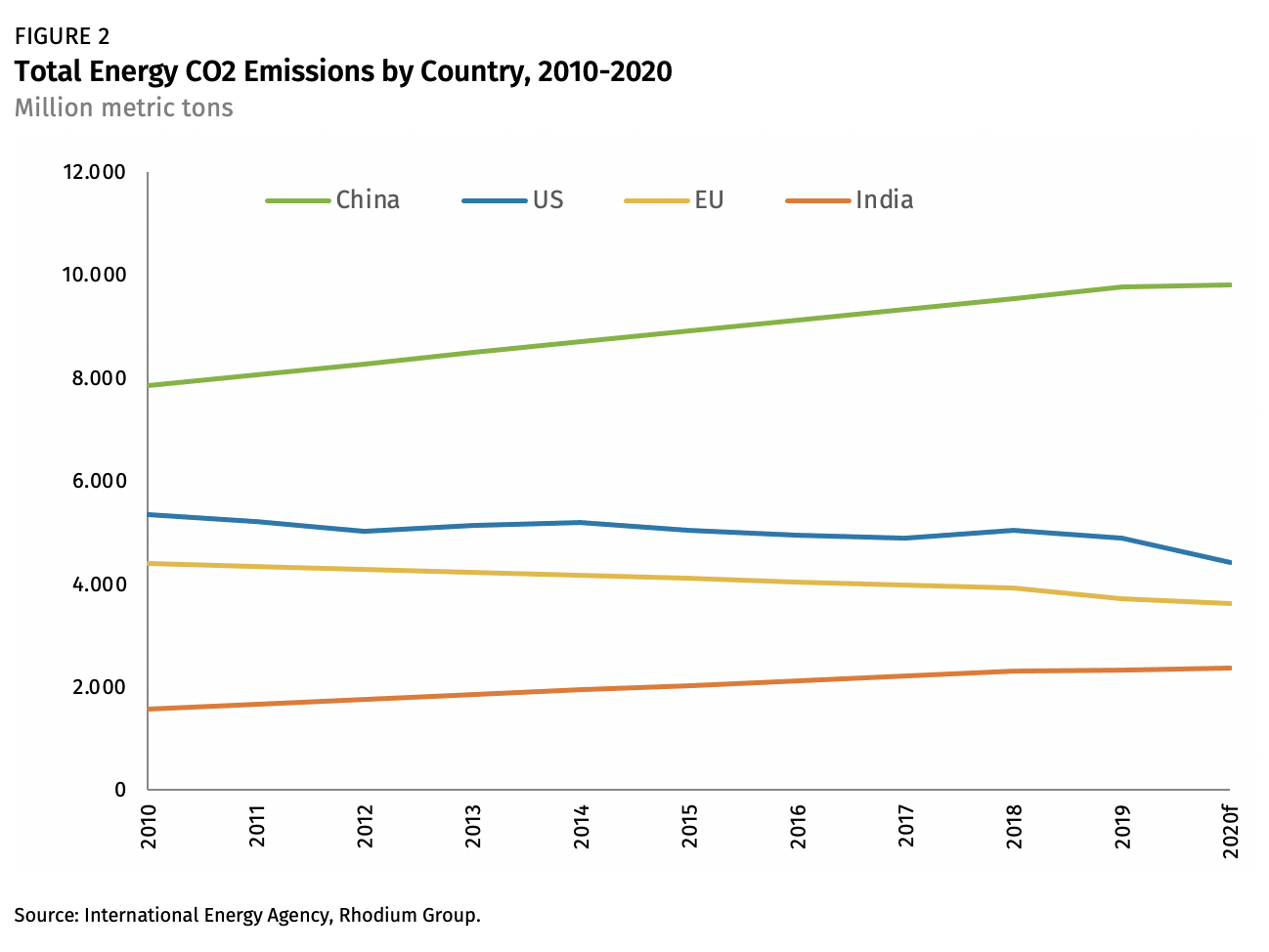

China is the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases and therefore a vital player in the global effort to combat climate change (Figure 2). Steps it could take to signal an accelerated near-term climate push would be to move up its goal of achieving a 20% non-fossil energy share by 2030, and by setting new targets to limit coal power capacity and total coal consumption (in the form of a peaking target or even a decline by 2025). Inclusion of non-CO2 goals (such as reducing methane and hydrofluorocarbons) could be an indication that the 2060 goal may go beyond carbon to include other more potent greenhouse gases. The extent to which China prioritizes clean energy will be somewhat of a bellwether for prospects of greening the global economic recovery.

The official readout of the Fifth Plenum will probably contain some description of Beijing’s preferred climate roadmap, but probably not enough to support a definitive assessment. In the 13th FYP cycle, a detailed climate policy plan (the “State Council 13th FYP Work Plan to Control Greenhouse Gas Emissions”) was released one year after the Party plenum that formulated the FYP. Nevertheless, with President Xi himself announcing the climate pledge this month and Vice-Premier Liu He’s October 21 public remarks (at the Financial Street Forum) discussing a low-carbon economy outlook in the context of “dual circulation,” there is political momentum behind the carbon neutrality pledge, so it may garner a significant share of the headlines from the post-plenum statement.

Disclosure Appendix

This material was produced by Rhodium Group LLC solely for the recipient. No part of the content may be copied, photocopied or duplicated in any form by any means without the prior written consent of Rhodium Group. Redistribution, forwarding, translation, or republication of this material in any form by you to anyone else is prohibited. Rhodium Group LLC is not an investment advisor. Any information contained herein not intended to be relied on as investment advice and this information is not purported to be tailored advice to the individual needs, objectives or financial situation of a recipient of this information. This report is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation, or an offer, to buy or sell any securities or related financial instruments. The information contained herein accurately reflects the opinion of Rhodium Group at the time the report was released. The opinions of Rhodium Group are subject to change at any time without notice and without obligation of notification. Rhodium Group does not receive any compensation from companies that may be mentioned in this report. No warranty is made as to the accuracy of the information contained herein.

© 2020 Rhodium Group LLC, 5 Columbus Circle, New York, NY 10019. All rights reserved.