From Fast Lane to Gridlock: Have Chinese Car Exports Peaked?

Trade barriers and outright bans in major markets like the US threaten to stall export momentum for China's automakers. Slumping export growth will put pressure on Chinese automakers, potentially leading to industry consolidation.

China’s auto industry has been a success story in recent years, with car exports emerging as a bright spot in an otherwise slowing economy. Between 2021 and 2024, the number of cars shipped from China surged by 300%, propelling China past Japan to become the world’s largest car exporter by units. However, this rapid growth now faces significant challenges. Trade barriers and outright bans in major markets like the US threaten to stall export momentum. Slumping export growth will put pressure on Chinese automakers, potentially leading to industry consolidation. But incumbent carmakers shouldn’t celebrate too much—even with slower export growth, Chinese carmakers are transforming into formidable global competitors in the auto market.

China’s car exports stall

Amid rising global EV adoption and Western automakers’ retreat from Russia, China has undergone a striking transformation—from an auto importer with limited exports to the world’s biggest auto exporter. However, after extraordinary growth in 2022 and 2023, China’s passenger vehicle exports are showing clear signs of deceleration in 2024.

Export growth reached 59% and 74% year-on-year during January–October 2022 and 2023, respectively, but has slowed to 26% over the same period in 2024. In value terms, monthly passenger vehicle exports reached a peak in October 2023, coinciding with the EU’s launch of its anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese EVs. In unit terms, export volumes continued to climb until August 2024, then driven by a rush to ship vehicles to Russia ahead of a planned hike in recycling fees in October 2024.

The export slowdown is primarily driven by waning demand, considering China’s auto sector has the capacity to produce significantly more vehicles and they are often offer higher margins in international markets. China’s passenger vehicle capacity utilization rate (CUR) fell from 74.7% in 2023 to 70.3% through Q3 2024 according to China’s official data due to a continued buildup of factories. While a handful of manufacturers, such as leading NEV producer BYD, are operating near full capacity, the industry as a whole lags behind the 80% CUR benchmark considered healthy in the auto sector. This means China could potentially produce and export an additional 4 million vehicles annually before reaching the healthy 80% CUR.

Six factors contribute to the apparent slowdown or early peak in export growth:

- Rising trade barriers: Both advanced and emerging economies are erecting a growing number of trade barriers against Chinese passenger vehicle exports (Figure 2). This underscores that the principal constraint on China’s vehicle exports is demand-related rather than supply-side.

- Inventory pressure: Our analysis of Marklines and Chinese customs data reveals that Chinese OEMs’ overseas sales have severely fallen behind exports since mid-2022. Chinese OEMs now hold nearly a year’s worth of unsold inventory abroad, much more than the two months of average retail sales inventories in China or the US (Figure 3). As firms frontload exports ahead of tariff hikes (or recycling fees in Russia) and adopt premium pricing strategies, inventory levels have surged since late 2023, especially in regions raising trade barriers. In the EU, they have reached a record 28 months,1 driven by weak electric vehicle (EV) demand and high Chinese EV prices (compared to China’s domestic prices). In Brazil, EV inventories hit 22 months after exporters frontloaded exports ahead of tariff increases, while inventories of Chinese exporters in Russia reached 16 months.

- Competition from Chinese overseas plants: While Chinese OEMs (with the exception of Geely’s acquisitions of Volvo and Proton) have traditionally concentrated production in China, this is changing rapidly. By 2027, we expect Chinese OEMs to increase their overseas production capacity by 1.5 to 2 million vehicles. A major driver of this growth is BYD, which has announced seven new overseas plants in recent months. These plants, some built due to growing trade barriers, will increasingly compete with Chinese exports. This is already evident in Thailand, where Chinese exports declined as Chinese OEMs’ local production ramps up.

- Joint venture (JV) constraints: Many producers suffering the most overcapacity are mass volume JV brands between Chinese and Western automakers. Our own calculations2 indicate that their CUR is far from healthy at only 36%. Foreign luxury brands, large private Chinese OEMs, EV startups, and even SOEs fared much better with CURs of 90%, 72%, 66%, and 64%, respectively. JV companies may hesitate to aggressively pursue third-market opportunities by exporting from China because they would directly compete with their own operations in ASEAN, Latin America, and Europe. They would also have to share profits from those efforts with their Chinese JV partners.

- Saturation of Russia’s market: China-based exporters have capitalized on low-hanging fruit in markets with high demand but limited supply, such as Russia, which has accounted for nearly 20% of China’s total car exports in 2024. Western OEMs exiting Russia in the wake of the Ukraine conflict and associated sanctions created a temporary vacuum that Chinese automakers filled. However, market opportunities in Russia are finite and cannot provide endless growth going forward. Carmakers expect sales in Russia to drop in 2025 due to extremely high interest rates.

- Slowing EV adoption: Outside of China, the growth of EV sales—both battery EVs (BEVs) and plug-in hybrids (PHEVs)—has slowed to 8% year-on-year through September 2024, down from 44% in 2023 and 23% in 2022. This is problematic for Chinese OEMs that have been more successful in capturing EV than ICE market shares globally. Chinese OEMs ex-China EV market share rose from 13% in 2023 to 17% in 2024, while their ICE vehicle market share has remained nearly flat at 4.7%. In this context, PHEV sales could offer some relief. These have fared slightly better than BEV sales in several overseas markets in recent months and are also less dependent on charging infrastructure, often a key obstacle to BEV adoption.

Who will remain open for Chinese cars?

China’s sustained supply-side support for its automotive sector and its unused production capacity position the country for continued global growth in the industry. However, this expansion depends on two critical factors: which major markets remain accessible to China-based car exporters and Chinese OEMs, and how Chinese companies adapt their strategies to enter and compete in these markets.

Host countries have three principal reasons for remaining open to imports of Chinese cars. The first is reciprocity. Many countries rely on access to China’s market and are reluctant to adopt measures that could provoke retaliation. Likely candidates for this include major exporting economies such as Germany, Korea, and Japan, as well as smaller countries that are economically intertwined with China. The second reason is practicality. Chinese vehicles are competitively priced, and importing them is a sensible solution for countries with limited or no domestic car manufacturing capacity. Finally, China’s EV leadership, particularly in areas such as lithium-iron-phosphate battery technology, lets host countries use innovative technologies developed by Chinese manufacturers to advance decarbonization goals.

Conversely, there are two primary arguments for restricting Chinese vehicles. The first is to protect local industries. The automotive sector is a significant source of well-paid manufacturing jobs and is politically sensitive in countries with established industries, particularly those with national carmakers like GM in the US, Toyota in Japan, and Togg in Türkiye. These countries are more likely to adopt protective measures, as seen in the EU’s decision to impose duties on Chinese EVs. The second argument is to protect national security. In countries that view Beijing as a strategic adversary, Chinese vehicles are increasingly seen as potential security threats. For example, US rationales for restricting Chinese connected vehicles encompass cybersecurity and data security risks, rather than just the erosion of domestic industry.

The main question is whether direct car exports from China will remain viable or if Chinese carmakers will have to invest in local production or partnerships. It’s also possible even that is not enough because Chinese ownership is seen as a risk. To tease out the answer, we analyzed the openness of global car markets to Chinese vehicles, both today and through 2027. This analysis considers current tariff levels, the significance of each country’s automotive industry, the presence of local champions, national security concerns around China and already ongoing policy discussions on tariffs and security-related restrictions.

Given the stagnation of global auto markets, with a few exceptions such as India, this framework enables us to assess the opportunities for China’s auto export potential in the years ahead. A number of blocs emerge that will determine the strategy of China-based exporters and Chinese OEMs:

- (De facto) banned bloc: An increasing number of countries are likely to close their markets to Chinese cars, even if locally produced, citing national security concerns. This bloc will likely make up around 17 million vehicles sold each year or 21% of global demand. Leading this group are the US and its USMCA partners, Canada and Mexico, which face strong US pressure to scrutinize Chinese imports and investments to safeguard the trade agreement. Close security allies like Israel are also introducing barriers, such as cybersecurity requirements for government tenders, which could end up becoming a ban on Chinese cars. While China remains an important market for Japan and Korea and they are eager to avoid Chinese retaliation, we expect that they will also effectively close their market to Chinese carmakers. First, there will be substantial US pressure to impose national security related restrictions, but they are also likely to maintain formidable non-tariff barriers to protect Korean and Japanese OEMs near-monopolies in their home markets.

- The restricted bloc, comprising around 21 million vehicles or 23% of the global market, includes the European Union, ASEAN, and close Chinese allies like Brazil and Russia. While outright bans on Chinese cars are unlikely, these markets have implemented or are expected to introduce trade barriers, primarily tariffs or duties, that make direct exports commercially unviable. ASEAN countries have set up incentivizes to promote Chinese investment. In Brazil, the EU, and Türkiye, there is also an uptick of Chinese carmakers manufacturing investment. In the EU, ongoing risk assessments on connected vehicles could lead to stricter national security restrictions, though a complete ban is improbable due to Chinese investments in Hungary and Spain, German carmakers’ fear of retaliation, and Geely’s ownership of Volvo. Instead, cost-competitive exporters like Tesla and BYD may absorb tariffs and continue exporting, especially if the yuan depreciates strongly.

- The open bloc represents approximately 10 million vehicles annually or 12% of the global market, including Australia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, the UK, and several smaller markets with annual demand below 300,000 units. Most of these markets either have no auto industry of their own or are trying to reset strained ties with China. This is why Australia and the UK, despite being close US allies, are likely to avoid putting tariffs or bans on Chinese cars in the near term. However, upcoming elections, particularly in Australia, could shift these dynamics and lead to greater restrictions on Chinese cars.

- Prospects for Chinese OEMs in India remain uncertain. India’s auto market, accounting for 5.5% of the global market, poses challenges for Chinese OEMs due to high tariffs—up to 100% on premium models—and restrictions on investment. While some exports continue under reduced tariffs—BYD’s knocked-down kits for local assembly, for example—strained India-China relations have limited broader market access. While exports will likely remain shackled, some Indian officials have recently advocated for more Chinese EV investment, suggesting opportunities for local production may slowly increase. That said, it remains unlikely that Chinese OEMs will dominate the Indian market.

Implications

This review of host countries’ openness indicates a likely ceiling for overseas demand for Chinese passenger vehicle exports. While exporting 10 million vehicles to open markets would represent a significant increase over current levels, and some Chinese manufacturers might even succeed in penetrating higher-tariff markets like the EU through exports, it is highly unlikely they will achieve complete market dominance in destinations such as Australia, Saudi Arabia, or the UK. Additionally, some of the open bloc markets will be served by Chinese OEMs’ overseas production, for example, Chinese brands made in Thailand being sold in Australia.

As a result, China will face substantial challenges in significantly expanding its passenger vehicle exports. This limitation has critical implications for China’s growth strategy, the evolution of its automotive industry, and its competitive positioning against established carmakers in third markets.

China’s growth strategy is changing

Given the rise in trade barriers, car exports—which made up 2.5% of China’s total exports or 0.5% of GDP through Q3 2024—are unlikely to become a major driver of China’s growth. At the start of 2024, Beijing highlighted exports of the “new three”—batteries, solar cells, and EVs—as part of its high-quality growth strategy. However, mentions of these sectors have become less frequent in policy documents and state media in recent months. Exports (in value terms) of lithium-ion batteries and solar cells declined year-on-year by 8% and 31% through November, while growth in passenger EV exports has slowed to 14%, due to overcapacity-driven price pressures (for solar), emerging trade barriers, and competition from Chinese-owned plants overseas.

While rising overseas production by Chinese EV manufacturers could boost auto parts exports, particularly batteries—this is what happened when German and Japanese OEMs started to invest overseas—this will not fully offset declining vehicle exports. This may become apparent in Thailand, where Chinese carmakers have shifted to local production to meet subsidy quotas, reducing overall auto export levels. Though some caution is warranted, as weak demand and production in Thailand this year likely also contributed to lower parts and battery exports.

For Chinese OEMs, there is a risk that Beijing could curtail overseas investment plans in an effort to keep auto exports high. In July 2024, China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) advised carmakers to avoid investing in certain regions, such as India and Turkey, and to limit activities to assembly operations rather than establishing full-scale manufacturing plants abroad. Still, while such directives may slow the pace of overseas investment, they are unlikely to halt it entirely. Beijing recognizes that establishing production facilities overseas is crucial for its automakers to secure market share and strengthen their global presence.

With passenger vehicle exports offering limited growth potential, Beijing must look for new sources of economic momentum. Boosting domestic demand is an obvious priority, especially since China’s domestic vehicle per capita ratio is still considerably below other middle-income economies like Brazil, Mexico, or Russia.

While China’s policymakers have long deprioritized consumption, there are some initial signs of shifting focus amid mounting challenges to export-driven growth. At the recent Central Economic Work Conference (CEWC), domestic demand and household consumption were identified as the top task for 2024. MOFCOM also announced plans for 2025 auto trade-in subsidy programs ahead of schedule, aiming to stabilize market expectations. Without these subsidies, domestic sales would likely have fallen further as consumers pulled forward purchases.

The trade-in programs have helped stimulate low-priced car sales by removing older vehicles from the market, creating opportunities for young and low-income buyers to afford their first car. While effective in the short term, achieving sustained growth in domestic consumption will require more fundamental reforms, particularly to China’s income distribution and tax systems.

Consolidation of China’s auto industry

Constraints on China’s future export growth could accelerate the ongoing process of industry consolidation. Many Chinese carmakers, particularly those operating at low margins like SAIC or currently lossmaking like Hozon, have been eyeing export growth as a pathway to profitability. In recent months, high export growth has enabled these firms to scale operations, optimize domestic production, and secure financing and policy support. Nearly all Chinese OEMs have recently increased the export share of their domestic production (Figure 7). New entrants have regarded exports as a lifeline, allowing them to survive in a domestic market that lacks the demand to support such a large number of players.

The stagnation of export growth poses significant challenges for carmakers with ambitious plans or exposure to markets with rising trade barriers. For instance, state-owned GAC aims to export 500,000 vehicles by 2027, a steep jump from 100,000 in 2024, but the target appears unrealistic amid heightened barriers. Failure to meet export goals, coupled with domestic sales slumps, could force even state-owned companies like GAC to downsize, sell assets, or face acquisition because they also see a decline in domestic sales due to woes in their JVs with foreign firms. In extreme cases, liquidation may be unavoidable. Even established exporters like SAIC will struggle as high duties in key markets like the EU render exports unprofitable. To access markets with trade barriers carmakers will need to set up overseas plants, a costly option only possible for the biggest players.

Challenges for incumbent carmakers in third markets

A peak or slowdown in China’s car exports will not provide incumbent carmakers much respite. Chinese car exports will increasingly be funneled to countries that have opted to remain open while the uptick in overseas auto production by Chinese OEMs will also create more competition in markets with trade barriers. China’s low production cost, leadership in EV technology, and its OEMs’ ability to sustain losses for longer due to subsidies will erode market shares for established carmakers in these regions, mirroring trends in China’s domestic market.

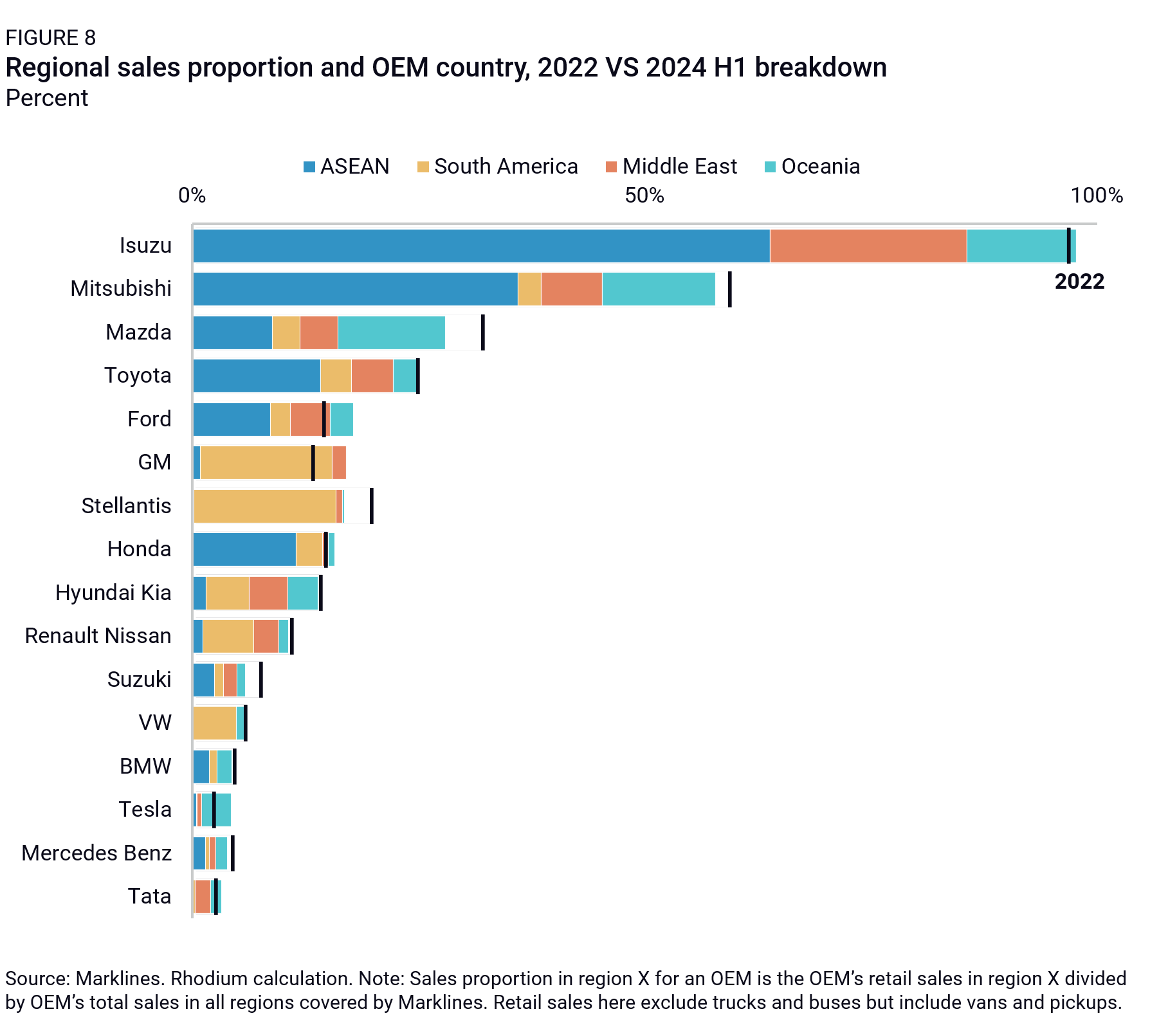

The firms most threatened by Chinese competition are smaller Japanese OEMs like Isuzu and Mazda, but also larger companies like Toyota and Ford that generate a lot of their sales and profits in markets that have low tariffs—Australia, the Middle East, the UK—or ASEAN, where Chinese OEMs can already produce locally (Figure 8). In Thailand, where Chinese OEMs have increased their market share from 5.3% in 2022 to 12.4% in 2024, this is already playing out: Suzuki and Subaru have announced plans to close their local plants. It also puts pressure on OEMs to merge, as in the proposed Honda-Nissan merger, coupled with their ongoing restructuring of their operations in Thailand.

In markets with high trade barriers but openness to Chinese investments, such as Brazil, the EU, and Turkey, the expansion of Chinese automakers will proceed at a slower pace and Chinese OEMs are unlikely to completely dominate these markets. But while tariffs and trade restrictions will hinder the internationalization of Chinese carmakers, they are not insurmountable obstacles. Subsidies from both Chinese and host governments, as well as Chinese carmakers’ access to cheap inputs from China, may allow Chinese OEMs to achieve cost advantages and undercut local competitors even overseas. With stagnating growth in these markets and local Chinese plants starting mass production in 2026 and 2027, declining market shares for incumbent carmakers seem inevitable. For instance, if Chinese OEMs achieve 80% of their planned production targets by 2027—granted a challenging goal—they could secure up to 15% of the South American market through local production alone. The share in Brazil would likely be much higher. This slower expansion through local production would impact a broader basket of Western OEMs. Stellantis and Volkswagen are particularly exposed, given their high sales share in both Europe and South America, but fellow mass-volume producers GM, Hyundai, Renault, and Toyota would also be hit.

We expect the USMCA region, Japan, and Korea to remain largely closed to Chinese competition. A slim chance remains that the Trump administration will selectively allow Chinese car investment but Chinese carmakers will not be able to claim a substantial share of the market in the US for the foreseeable future. However, even without direct competition, incumbent OEMs in these protected markets will feel the impact of Chinese manufacturers transforming into global players. As Chinese OEMs intensify competition in China and third markets, incumbents are likely to focus on growing their share in protected markets like the US, increasing competitive pressure. At the same time, the Trump administration will push for export opportunities for US OEMs in Japan, Korea, and the EU, potentially intensifying market share losses for incumbents in these regions.

Footnotes

Excluding Volvo and Smart for EU since some local production is for exports to other markets.

Rhodium calculation based on Marklines data.