The Clawback: Reclaiming Strategic Assets from China

The United States is on an unspoken mission to claw back strategic assets from China.

The United States is on an unspoken mission to claw back strategic assets from China. This is not a policy that began with the current US administration, nor has it been articulated in a speech or policy document. Instead, this is a pattern of observed behavior driven by growing US anxiety over growing dependencies on China in critical industries and infrastructure. Of course, the urgency to diversify away from China in sensitive sectors is not just a US phenomenon: Partner countries are working toward a similar goal, but their tactics will be subtler than their American counterparts and may still leave a door open for (conditional) Chinese investment. As the clawback becomes more visible in the coming months and years, expect Beijing to push back with tighter restrictions on outbound investment as it tries to hold onto prized assets from a decade-long M&A spree.

Big regrets

While there is a growing consensus in Washington that dependencies on China for critical goods and infrastructure constitute a major national security risk, the task of unwinding them has proven vexing. Tariffs or outright bans on China-origin products, from critical minerals to wireless routers, still requires time for other companies to fill the void and bring new production online, all while trying to remain cost-competitive amid rising trade uncertainty. But there is also a swifter path to resolving the dependency dilemma: the clawback, which we define as using various policy instruments to make it untenable for a strategic asset to remain under Chinese ownership on national security grounds. We have observed a collection of signals over the past year that indicate the clawback is taking shape, not just in the US, but also in partner countries that share similar anxieties over the presence of Chinese companies in strategic industries.

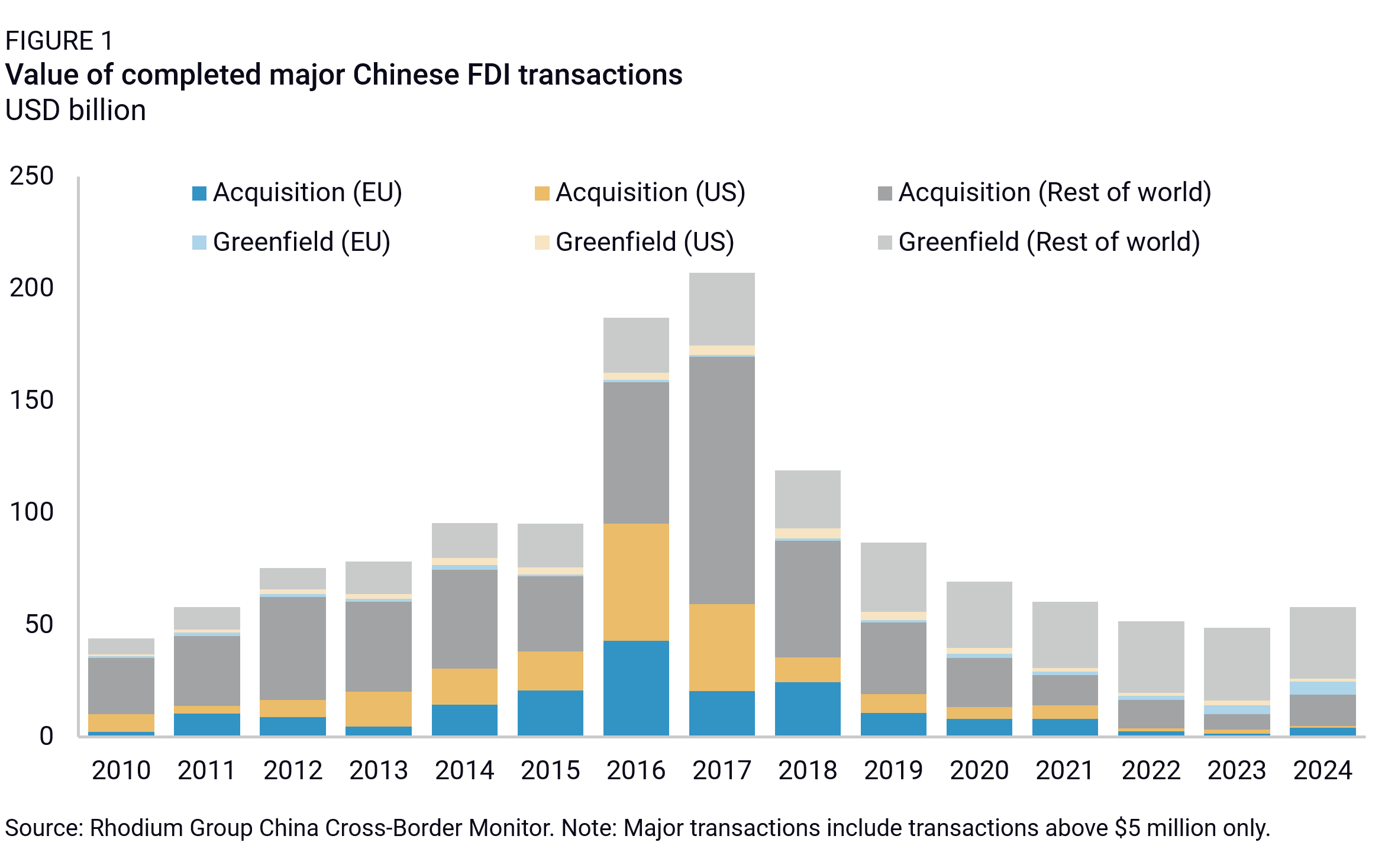

The clawback story is rooted in remorse. China’s global outbound investment saw rapid growth in the 2010s as Chinese firms—largely shielded from the worst effects of the global financial crisis—looked to new markets to expand and diversify. Companies were hungry for capital and geopolitical disruptions were waved off by investors as tail risks. When Beijing loosened restrictions on outward FDI in 2014, Chinese investment reached record highs of $200 billion in 2016 with an explosion of large-scale M&A deals. The bulk of China’s investment flows went toward acquisitions in developed markets in the US and Europe. But there are scores of transactions that took place during this period that would have had little chance of making it past national security filters in today’s geopolitical climate.

Such “big regret” deals include Chinese biotech giant BGI’s acquisition of US DNA-sequencing startup Complete Genomics in 2013, Hong-Kong conglomerate WH Group’s acquisition of US pork producer and food-processing giant Smithfield Foods in 2013, Chinese firm Midea’s acquisition of German robotics industry leader Kuka AG in 2016, the acquisition of Dutch legacy chip manufacturer Nexperia by a consortium of Chinese investors in 2017, and the ChemChina acquisition of Swiss agricultural technology firm Syngenta in 2017, among others (Table A1).

Rebuilding an industrial base and reorganizing global trade is hard. The US is bound to seek out shortcuts in response to growing urgency to diversify away from China in critical sectors. As the US works to create ex-China technology and trade blocs, it will naturally be tempted by assets that once belonged to a network of trusted allies, or even by Chinese-owned assets that have become dominant in certain sectors of the US economy much to Washington’s regret. These are prime targets for policies aimed at rebuilding supply chain resilience and technological competitiveness at full tilt.

The clawback in action

Several examples have surfaced over the past year of US attempts to claw back assets, usually through policies that force the question of whether Chinese ownership of assets in critical sectors is a sustainable business strategy. Each case study is unique in circumstance and methods, and many are still in early stages of the divorce process, but all speak to this broader trend of the US (and other like-minded governments) pursuing creative pathways to downsizing or outright eliminating Chinese stakes in key assets. This even includes some cases where the original owner and creator of the asset is Chinese or simply China-linked, yet the asset itself is critical enough to justify a takeover.

Hutchison Ports and BlackRock

When addressing the US Congress on March 4, Trump stated, “my administration will be reclaiming the Panama Canal, and we’ve already started doing it.” He was referencing a deal negotiated at breakneck speed for a consortium of investors involving BlackRock, its subsidiary Global Infrastructure Partners, and Mediterranean Shipping Co.’s Terminal Investment Limited, to acquire a controlling stake of Hong Kong-based CK Hutchison Holdings Limited in a $22.8 billion deal covering 43 ports across 23 countries. The mega deal includes a 90% stake in the Panama Ports Company, which operates the ports of Balboa and Cristobal, not to mention nearly the entirety of the company’s international port portfolio save for its port operations in Hong Kong and mainland China.

Trump has made no secret of his expansionist ambitions to redraw the map of the United States. The US president is applying 19th century geopolitics and his real estate instincts to the dependency dilemma, trying to create the conditions for the US to assert control over territory to bridge critical supply and infrastructure gaps. In the Panama Canal example, the Trump administration asserts that critical port infrastructure was effectively in Chinese hands (since the US government regards Hong Kong as a political appendage of Beijing since the 2019-2020 crackdown), and that a naval chokepoint controlled by China constituted a national security risk to US trade flows and military movements. The Trump administration was already signaling its intent to litigate the provisions of historical treaties governing the Panama Canal. When the US transferred control of the canal to Panama in 1999, it was on the condition that “neutrality” of the international waterway would be preserved—a provision that could be challenged by the US allegation of Chinese control over port infrastructure. The treaty also explicitly states that the United States has the primary responsibility to protect and defend the Canal, to include the right “to take unilateral action to defend the Panama Canal against any threat.” In a sign that US pressure was working, Panama withdrew from China’s Belt and Road Initiative on February 6.

Seeing the writing on the wall and eager to take the check, the CK Hutchison family conglomerate signed off on the $22.8 billion deal but must now answer to authorities in Beijing who regard the transaction as a betrayal of China’s global ambitions. On the heels of multiple opinion pieces in pro-Beijing media condemning the deal as “spineless groveling,” Beijing-backed Hong Kong Chief Executive John Lee said “any transaction must comply with the legal and regulatory requirements.” The ball is now in Beijing’s court: Chinese officials could assert pressure on Hong Kong to invoke its National Security Law to disrupt the transaction on the grounds that the deal stemmed from collusion with foreign officials. Beijing could also assert extraterritorial writ via its Anti-Monopoly Law given CK Hutchison’s market exposure in China. While Beijing would be challenging the deal on anti-competition and national security grounds, the US would argue that the carveout of Hong Kong and mainland ports mitigates this risk. This dynamic effectively pits a Chinese national security argument against a US one, with Washington ready and willing to re-litigate the Panama Canal treaties to get its way.

Wuxi Group’s pre-emptive restructuring

In some cases, US policy proposals are preemptively forcing corporate selloffs of Chinese assets even before those policies become law. This can be seen in the effects of the draft BIOSECURE Act, which is a response to rising US concerns over Chinese firms’ deepening role in American health supply chains and in the sensitive domain of biotech in particular. The bill, which was introduced in January 2024 and had companion versions in the House and Senate, sought to prohibit US federal agencies from contracting with certain named “biotechnology companies of concern.” The bill explicitly named five Chinese companies—BGI, MGI, Complete Genomics (which was acquired by BGI in 2013), Wuxi AppTec, and Wuxi Biologics, along with their subsidiaries, affiliates, and successors—but also left the door open for additional firms from foreign adversary countries to be added to the list. The proposed restrictions extend beyond these named firms, barring federal agencies from working with any biopharmaceutical manufacturer which would use equipment or services from these entities in fulfilling federal contracts.

The BIOSECURE Act advanced steadily through committee, gaining bipartisan traction along the way and comfortably passed the House in late September. The bill failed to make it in the final cut of the year-end of National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) and continuing resolution (CR), but there is strong potential for the bill to be reintroduced in the current Congress.

Even though the bill has not been formally enacted into law, it has already created a chilling effect on Chinese biotech firms. In late December 2024, Wuxi AppTec—one of the firms most exposed to the proposed restrictions, with 65% of its revenue derived from the US market—announced the sale of its cell and gene therapy manufacturing units in the US and UK to American investment firm Altaris. A month later, Wuxi Biologics—the second most exposed, generating 47% of its revenue from the US—disclosed the sale of its vaccine manufacturing site in Ireland to Merck, the facility’s sole client.

Neither company has explicitly linked these divestments to the BIOSECURE Act, but the timing suggests that the not-yet-enacted bill is already prompting strategic restructuring to shed assets ahead of any formal restrictions, and to optimize margins in anticipation of mounting geopolitical headwinds.

Other Chinese biotech players also appear to be shifting into preemptive damage control mode. A notable recent example is US firm Legend Biotech’s boardroom maneuvering to distance itself from the Chinese contract development and manufacturing organization GenScript, its majority shareholder. The board suspended some of GenScript’s voting rights—a possible attempt to limit control without triggering direct divestment. The move came just months after lawmakers from the House Select Committee on the CCP requested an intelligence briefing from the administration on GenScript and its US-based subsidiaries: Bestzyme, ProBio, and Legend Biotech. This has fueled speculation that GenScript could be added to the list of “biotechnology companies of concern.” While GenScript still retains a sizeable 47% stake in Legend Biotech, making the company highly susceptible to US regulatory scrutiny, Legend’s board may be making pre-emptive move ahead of regulators’ questions on its Chinese links.

Volvo’s Geely dilemma

The US has a powerful clawback weapon in the form of Commerce’s Information and Communication Technology and Services (ICTS) rule. With this rule, the US can leverage its economic clout to force companies to restructure their supply chains and sever ties with Chinese ICTS suppliers if they want to preserve a foothold in the US market. As a result, Chinese ownership can become an instant liability for companies that need to preserve US market share.

ICTS restrictions that went into effect on March 17 require automakers selling into the US market to rapidly phase out certain Chinese hardware and software on the grounds that such technologies create undue national security risks, including sabotage (See Car Trouble: ICTS Rules Rewire Auto Supply Chains). The restrictions also ban sales of vehicle (model year 2027) if the manufacturer is owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction of China. This is troubling news for Volvo, a Swedish company, which is majority-owned by Zhejiang Geely Holding Group. Given that Volvo cars are popular among American consumers and that the US market makes up roughly 16% of Volvo’s global sales, we can infer that Volvo’s leadership is unlikely to forfeit the US market in response to the new restrictions. And this is precisely the point: The US rule allows for “special authorization” licenses for companies caught in a bind, so Commerce can leverage the license to press a firm like Volvo on its plans and timeline to “resolve” its Chinese ownership problem. We would expect that Volvo will face significant pressure to undergo a corporate restructuring. This could entail selling off its US operation or further discussion around the viability of Geely’s majority stake.

Pirelli’s tire pressure

The case of Italian tire maker Pirelli reveals how twin pressures coming from both Washington and a foreign government can combine to create the clawback effect. Chinese state-owned Sinochem invested in Pirelli in 2015 through its subsidiary, ChemChina, which acquired a controlling interest in the Italian tire maker for $7.7 billion. (ChemChina later merged with Sinochem). When Pirelli notified Rome of its intention to renew Sinochem’s shareholder agreement in early 2023, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s government saw an opportunity to intervene. The Italian government used its so-called Golden Powers, which allow Rome to review transactions in a broad set of strategic sectors, to impose several governance measures. These included capping Sinochem’s board presence to nine of fifteen seats (with key decisions requiring an 80% supermajority), stripping Sinochem of the ability to appoint the CEO, severing organizational and functional ties between Pirelli and Sinochem, and banning transfer of cyber-derived data to China. Rome’s justification for the intervention was notably a bit of a stretch, arguing that advanced sensors embedded in Pirelli tires collect sensitive data.

After Italy opened an investigation targeting Sinochem for a potential breach of the mitigation terms in November 2024, the controversy over Sinochem’s ownership is once again coming to a head. This time, however, US moves in the auto market are driving justification for the company’s leadership to demand that Sinochem shave down its 37% stake. The FT reported that a proposal has been put forth for Sinochem to reduce its stake to less than Italian shareholder Camfin’s 26.4% holding through share buybacks that can be immediately resold on the market. US ICTS restrictions on connected vehicles were cited as the justification: Restrictions covering Pirelli’s tire sensor technology could result in the firm losing 25% of its total North America revenue due to the rules banning use of certain components by Chinese-owned suppliers. The current ICTS scope does not cover tire sensors, so this may be a preemptive move that the firm is making to justify another intervention to shave down the Sinochem stake. Moreover, the Trump administration’s 25% tariff on vehicles and auto parts is yet another pressure point on the company. The tariffs are designed to drive manufacturing investments in the United States, but Pirelli’s high exposure to a Chinese-owned company like Sinochem could complicate the company’s continency planning to preserve its North American market share.

Nexperia and Wingtech

The US can extend a long arm to force the clawback of strategic assets back into the partner fold. A prime case study centers on the Netherlands-based firm Nexperia, which produces mature node semiconductors and components for the automotive and industrial sectors.

Nexperia is a dizzying story of changing hands. Nexperia spun off from Dutch semiconductor firm NXP in 2017, when it was sold to a consortium of PRC state-affiliated investors led by JAC Capital and Wise Road Capital. Two years later, those initial investors turned around and sold Nexperia to Wingtech, a Chinese contract manufacturer of mobile phones and other electronic devices. After the acquisition, Nexperia claimed it would remain an independent Dutch company. But four months later, Wingtech founder Wing Zhang took over as CEO and instituted a broad management change that UK investigators described as a “stealth board takeover.” The result is a 100% Chinese-owned and Netherlands-based firm producing legacy chips primarily for the Western market.

This proves problematic as the US and G7 countries grow increasingly anxious that China’s rapid buildout in semiconductor manufacturing capacity will make them dependent on China for another foundational technology critical to the defense, automotive, and medical industries (see Thin Ice: US Pathways to Regulating China-Sourced Legacy Chips). Given the immense cost and time it takes to bring new fabs online, not to mention the challenge in incentivizing chipmakers to allocate production capacity to mature node chip production when advanced node chipmaking fetches much higher revenue, it is only logical that European and US governments will look first to assets within their borders to address their growing legacy chip dilemma.

In this case, it was the UK government that initiated a partial clawback from Nexperia. The British House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee lobbied for a review on the grounds that the UK’s largest semiconductor manufacturer owned by a company backed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) posed a critical national security risk. The UK government completed a security review in November 2022 and retroactively forced Nexperia to sell its stake in Newport Wafer Fab. After adopting an investment screening act in 2023, the Dutch government did its own retroactive review of Nexperia’s purchase of chip startup Nowi the same year. However, the Hague ultimately approved the deal after imposing security safeguards and made a controversial determination that Nexperia could be considered a Dutch company despite the fact that the firm remains 100% owned by Wingtech and is headed by Wingtech founder and CEO Wing Zhang.

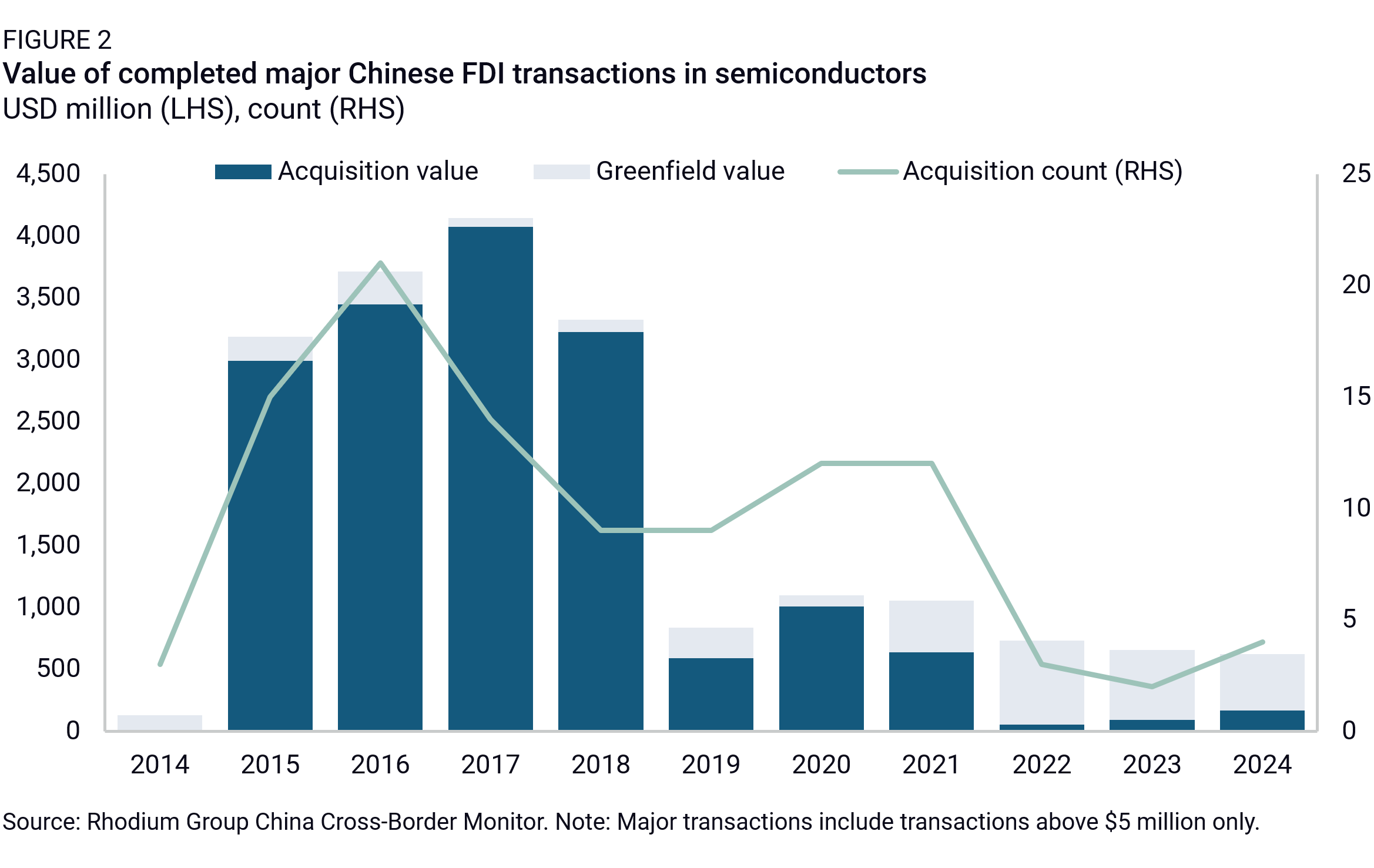

The US now wants to push the Hague to finish the job on the Nexperia clawback. In December 2024, Commerce BIS added Nexperia’s Chinese owner Wingtech, along with the financiers of the Nexperia acquisition, Wise Road Capital and JAC Capital, to its Entity List for promoting China’s chip development via strategic investments and acquisitions. JAC Capital and Wise Road Capital sought out investments in strategic semiconductor assets and primed them for Chinese takeover. As investment scrutiny grew, Chinese-owned semiconductor firms shifted increasingly to greenfield investments with a focus on expanding capacity for mature node semiconductors (Figure 2, Table 1).

With their inclusion on the BIS Entity List, the US turned the Chinese stakeholders surrounding Nexperia into liabilities. But the US move appears to also have had an unintended consequence: On the heels of the listings and subsequent cancellations of big purchase orders by clients like Apple, Wingtech immediately sought to raise cash by striking a deal to sell Wingtech’s entire product assembly business to Chinese electronics giant Luxshare. As a result, Apple and other former Wingtech clients for product assembly are now even more dependent on a Chinese electronics manufacturer, while Nexperia (for now) remains in Wingtech’s hands.

Big questions lie ahead. Will Washington or the Hague attempt to disrupt the Wingtech-Luxshare transaction? Will a severe downturn in US-EU relations under the Trump administration impede the Hague’s quiet efforts to address Nexperia’s Chinese ownership? Alternatively, will heavy US pressure on the Netherlands over semiconductor export control alignment and economic security standards for legacy chip production end up accelerating a Nexperia restructuring? This clawback story appears to be approaching its climax.

Qualified divestiture: TikTok on the clock

TikTok, which faces an April 5 deadline to perform a “qualified divestiture” from its Chinese parent ByteDance, is the most high-profile example of the US taking over a Chinese asset. The move has been based on concerns that the popular social media app puts American data security at risk and exposes Americans to Chinese censorship and influence campaigns. Apart from the fate of TikTok itself, which has become a bargaining chip for the Trump administration, the legal precedent created by Congress’s so-called “TikTok bill” on forced divestitures is the bigger story. We expect this potent clawback tool in the US arsenal will be applied to cases beyond TikTok.

In April 2024, the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act (PAFACAA), also known as the TikTok bill, was signed into law, prohibiting any entity from distributing, maintaining, or updating a “foreign adversary-controlled application” within US borders unless the application completes a “qualified divestiture” within a set timeframe. According to the law, a qualified divestiture requires the president to certify that, after the transaction, the application is no longer controlled by—and has no operational ties to—a foreign adversary.

TikTok, ByteDance, and other stakeholders sought to stop the legislation, but the DC Court of Appeals, and subsequently the Supreme Court, upheld the constitutionality of the law, and the notion of “qualified divestiture.” Notably, the DC Court of Appeals rejected TikTok’s argument that the law constitutes a prohibited legislative punishment under the Bill of Attainder since the qualified divestiture exemption grants the platform a pathway to overcome the prohibitions in the Act and return to the US market..The court also rejected TikTok’s claim that it constitutes a regulatory taking (i.e. an uncompensated taking of private property) because the law’s qualified divestiture exemption leaves TikTok “a number of possibilities short of total economic deprivation.”

The courts’ rulings carry implications well beyond the TikTok case. First, it opens the door for the President to invoke PAFACAA to mandate the qualified divestitures of other “foreign adversary-controlled” apps which meet the law’s criteria. Second, it sets the stage for the concept of qualified divestiture to be replicated in other legislative efforts targeting Chinese ownership in sensitive sectors under congressional scrutiny.

All eyes are now on how Trump 2.0 handles the TikTok case. The deal he brokers will establish the baseline for what constitutes an acceptable restructuring—and will test the limits of his transactional approach when it comes to how much residual Chinese ownership or influence, if any, is considered tolerable.

Expanding the toolkit

Eye on CFIUS: Retroactive reviews?

Though the tactics in the case studies above vary widely—from highly transactional executive deal-making to turning Chinese assets into liabilities via entity listings—the natural place to look for clawback authorities is the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). While CFIUS has become more assertive in recent years in reviewing and blocking investments with problematic Chinese linkages, it still faces jurisdictional limitations especially on unwinding closed transactions. The Trump administration made clear in its America First Investment Memo that it is already considering expanding CFIUS’s jurisdiction to new sectors and new types of transactions. We are now watching whether this momentum also results in a move by the current administration to expand CFIUS’s authority to support clawbacks on retroactive deals.

With the passage of the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act in 2018, CFIUS gained relatively broad powers to retroactively review “non-notified” transactions, or deals that fit within CFIUS’s scope of covered transactions but were not properly notified for review. The committee has a dedicated team to review thousands of potential deals every year, and has taken already action under its non-notified authority to unwind deals well beyond their close. For example, CFIUS reportedly required Chinese gaming company Beijing Kunlun Tech to sell off US dating app Grindr in 2019, ostensibly owing to concerns over access to users’ sensitive personal data and geolocation. The forced unwinding came three years after Kunlun had first gained effective control of the company in 2016. But ultimately, CFIUS’s retroactive review of non-notified transactions is still bound to deals that fall within its scope of covered transactions. For now, this still notably excludes most greenfield investments1—an increasingly visible gap now drawing scrutiny from Congress and the administration.

CFIUS’s power to unwind transactions that it has officially reviewed is even more constrained. Transactions that were formally notified and either cleared without further action or subject to a mitigation agreement receive a so-called “safe harbor” from retroactive review. CFIUS may only waive this safe harbor in cases where parties have “submitted false or misleading material information” or “materially breached”2 a mitigation agreement or condition, and if “the Committee determines that there are no other adequate and appropriate remedies or enforcement tools available to address such breach.” This amounts to a high legal bar that risks lengthy court battles and limits CFIUS from revisiting deals based on shifting perceptions of national security concerns.

CFIUS has increased its enforcement of mitigation agreements in recent years, most notably issuing a $60 million penalty against T-Mobile for breaching mitigation terms. But Trump 2.0’s America First Investment Policy Memo announced an intent to abolish mitigation agreements altogether for deals involving investors from foreign adversary states like China. The memo described mitigation agreements as “overly bureaucratic,” “complex,” and ultimately insufficient for resolving national security risks. The administration’s tweaks to investment screening still need to take shape but we are watching whether the Trump administration and Congress try to lower the bar for revisiting ongoing mitigation agreements.

Quectel and the limits of licensing

The ICTS rule will be deployed against multiple targets, especially as US concerns intensify over data security and cybersecurity breaches from critical infrastructure laden with Chinese ICT components. As the Volvo/Geely example demonstrates, outright bans on Chinese-owned products and services could compel a corporate restructuring to preserve US market share. But one of the ways Chinese firms could try to get around such restrictions is through creative licensing deals with US firms hungry for Chinese tech.

The ICTS final rule (Dec. 2024) included an expanded scope to cover 11 emerging technologies, including:

- Advanced network sensing and signature management, advanced computing;

- Artificial intelligence;

- Clean energy generation and storage;

- Data privacy, data security, and cybersecurity technologies;

- Highly automated, autonomous, and uncrewed systems and robotics;

- Integrated communication and networking technologies;

- Positioning, navigation, and timing technologies;

- Quantum information and enabling technologies;

- Semiconductors and microelectronics; and

- Biotechnology

The final rule also included expansive language on what transactions involving Chinese stakeholders could be subject to investigation. According to the rule, a company can be considered owned or controlled by a foreign adversary “through the ownership of a majority or a dominant minority of the total outstanding voting interest in an entity, board representation, proxy voting, a special share, contractual arrangements, formal or informal arrangements to act in concert, or other means, to determine, direct, or decide important matters affecting an entity.” The broad scope would presumably capture licensing deals, which is particularly notable given attempts by US automaker Ford to forge a technology licensing deal with Chinese battery maker CATL for investments in the US. Ford was creating a template for companies to compensate for technology gaps in an area dominated by Chinese suppliers but has been hitting stiff political resistance at the local and federal level.

The test is whether a company can secure political support to pursue a licensing deal to acquire critical know-how and with the intent of shedding its Chinese linkage when self-sufficiency is attained. The Trump administration’s approach to such transactions still needs to be tested. US companies may try to probe the bounds of the ICTS rule by making the case that outright bans will leave critical gaps and that instead, technology licensing deals are the quickest and most effective pathway to bringing necessary IP into American hands. US startup firm Eagle Electronics is a case in point: The Ohio-based firm is on a mission to reshore electronics supply chains and create American jobs, starting with cellular modules. Notably, the firm has struck a partnership with Chinese internet of things (IoT) giant Quectel to license the Chinese firm’s technology to manufacture cellular modules in Ohio. The IoT domain is already under intense scrutiny by US policymakers over the cybersecurity and data security risks stemming from China’s global dominance in IoT modules and the pervasiveness of such components in US critical infrastructure. If Eagle Electronics can make a convincing security argument that a temporary alliance of convenience with a Chinese tech supplier is the swiftest path to diversification, then other corporates could follow.

But there’s a catch: if Beijing suspects that US companies are following a “reverse IP transfer” playbook, with the goal of ultimately divorcing their Chinese partner once they achieve self-sufficiency, Chinese regulators may tighten up outbound investment restrictions and export controls to prevent such transactions.

When couples therapy fails

Divorcing a Chinese corporate parent is complicated. There is no one method to doing it, but there are several tactics that are known to be practiced and that are usually negotiated behind the scenes among corporate boards and teams of lawyers. Some tactics include the following:

- IPO exit strategy: A negotiated outcome could result in the Chinese owner selling down its stake over time via a public listing. This can typically involve a bargain between the two parties in which the owners of the asset trying to shed Chinese ownership sell non-critical assets to the Chinese owner while the Chinese stakeholder agrees to an IPO to create an escape route and sell down its stake.

- Sell majority stake to a financial investor: If the asset in question sells to a private equity firm on a mandate to cut spending, it can create the conditions to sell the Chinese stake more rapidly once the entity is on the financial hook to restructure.

- Dilute the stake with a merger: The asset in question could pursue a merger with a much bigger entity to effectively dilute their Chinese stake. The Chinese stakeholder can then wind down its share over time.

- Split the baby: Through a negotiated settlement, the asset in question could retain parts of the business that services the Western market while selling the parts of the business serving the Chinese or broader Asian market to the Chinese owner.

- Pick a side: In some cases, a company may make a judgement about where the bigger market opportunity lies and attempt to divorce their host government. Re-domiciling a business would entail changing legal jurisdiction from China to the United States (or other jurisdiction) and de-registering the business in China. This is a complicated pathway, however. The US has grown alert to Chinese companies registering in jurisdictions like the Cayman Islands. For example, US Treasury outbound investment restrictions in sensitive technologies can be applied extraterritorially to entities, even if domiciled outside China, Hong Kong, or Macau. If the Chinese company’s leadership has dual citizenship in the US or partner country and drops their Chinese citizenship altogether, along with any other business linkages in China, this could mitigate the risk in the eyes of US authorities. However, the Chinese entity would still have to be alert to attempts by Chinese regulators to disrupt such moves as well as US regulations that could apply a broader scope to what constitutes exposure to China.

Beijing strikes back

Beijing is growing alert to the clawback playbook. The growing backlash against the CK Hutchison port deal in China’s state media, along with recent reporting that several Chinese agencies have been instructed to examine their options to review the transaction, indicate that Beijing is preparing its toolkit to disrupt clawback attempts as well as preemptive moves by companies seeking to distance themselves from their Chinese parents. Beijing’s response may take multiple forms, ranging from political pressure to legal and regulatory maneuvers.

Export controls

Beijing could attempt to blunt the sale of certain Chinese-owned assets through targeted export controls on key technologies. This was Beijing’s playbook to thwart the initial forced sale of TikTok in 2020: MOFCOM added “personalized information push-service technology” to its technology export control catalogue, which was widely understood to capture TikTok’s prized recommendation algorithm. Since then, MOFCOM has steadily broadened its export control regime to cover a wider array of strategically sensitive technologies, including those related to rare earth refining and extraction, drone systems, and LiDAR. More recently, MOFCOM has signaled possible controls on EV battery cathode production technologies, as well as lithium and gallium extraction. While the controls primarily reflect China’s desire to preserve its technological edge, they also offer preemptive leverage in sectors where Chinese firms are facing growing scrutiny.

Merger control

China’s merger control authority, the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), has the authority to investigate transactions—even those outside China’s borders—when the parties involved meet certain revenue thresholds in China. SAMR also reserves the right to review below-threshold transactions if it believes the deal could impact fair competition in China. This gives SAMR ample leeway to scrutinize a broad range of transactions on anti-competition grounds, including cases where a Chinese majority stake is sold to foreign financial investor, or where the Chinese stake is diluted as part of a merger.

For example, SAMR could investigate the CK Hutchison port deal on the grounds that the BlackRock-led consortium would gain a dominant market position and potentially restrict access for other operators in ways that harm China’s national security. In 2014, MOFCOM (which dealt with some merger review before SAMR was created in 2018) blocked a proposed vessel-sharing agreement between European shipping giants Maersk, MSC, and CMA CGM, arguing it would restrict competition on Asia–Europe shipping routes.

Short of formally or informally prohibiting a transaction,3 SAMR could also impose intrusive conditional remedies that make it difficult for all parties to satisfy SAMR’s demands and complete the transaction. In recent years, SAMR’s remedies have grown more creative in a bid to blunt the effects of US tech controls, with conditions such as requirements for parties to maintain production and R&D in China, maintain prices, transfer IP, and even allow stockpiling for Chinese customers.

But if Beijing relies on SAMR to challenge politically loaded transactions like the CK Hutchison port deal, the move could backfire. China has already weaponized SAMR reviews in probing US big tech firms like NVIDIA. If the US sees SAMR as a tool to disrupt the top priorities on its national security agenda, then it could argue that SAMR’s review is invalid and provide legal backing to its own firms to not recognize SAMR’s authority. It would then be up to Beijing to decide whether to apply punitive action to the asset exposed directly to the China market and rely on intimidation tactics to try and get the China-exposed party to ditch the deal on its own. To this end, China has reportedly instructed state-owned firms to pause new deals with businesses linked to Hong Kong business magnate Li Ka-shing and his family over the CK Hutchison deal.

National security review

There are several provisions of varying levels of specificity scattered across China’s national security laws that Beijing could invoke to review foreign investment transactions that threaten its national security (Table A2). Notably, the NDRC and MOFCOM jointly established a CFIUS-style working mechanism in 2021 under the updated Foreign Investment Security Review Measures. These measures empower the joint working mechanism to investigate, mitigate, or prohibit transactions in certain strategic sectors, including cases where “foreign investors obtain equity or assets of domestic enterprises through mergers and acquisitions.”

There has been speculation that China could invoke this mechanism to review the CK Hutchison port deal, though questions remain as to whether the measures, as currently written, allow Beijing to probe deals involving offshore companies like CK Hutchison or involving assets outside China’s borders.4 That said, Beijing could likely engineer a creative workaround or update the wording of the regulation if it chooses to pursue this pathway. To date, there has been no public reporting of deals being formally reviewed under this authority, making it difficult to precisely gauge the range of China’s defensive options through national security reviews.

Overseas listing review

Beijing could also intervene via the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), its securities regulator, in cases where firms try to IPO outside mainland China to reduce their Chinese stake. The CSRC’s measures governing overseas listings grant it broad discretion to prohibit domestic companies from listing overseas if this would jeopardize national security. The CSRC’s purview extends not just to IPOs, but also to a broad range of post-listing activities including follow-on share issuances, secondary listings, share swaps, transfers of shares or M&A activities. This gives the CSRC a powerful lever on listed firms attempting to wind down Chinese ownership.

Sanctions

Beijing also has a growing arsenal of sanctions mechanisms it can deploy in response to US clawback efforts. These are more likely to be applied asymmetrically than in tit-for-tat fashion. Tools such as the Unreliable Entities List and the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law provide legal grounds for China to target foreign firms or individuals that are seen as threatening national interests. Chinese regulations explicitly state that foreign entities that support, implement, or assist in the implementation of discriminatory measures against China’s national security interests could land on its sanctions lists. US gene-sequencing specialist Illumina’s recent inclusion on the Unreliable Entities List was reportedly tied to its lobbying efforts in favor of the draft BIOSECURE Act, which, as explained above, could force Chinese biotechs to divest from their activities.

Beijing could continue targeting foreign firms it sees as supporting clawback-related policies or escalate by sanctioning Chinese parent companies in the early stages of the “divorce process” as a deterrent to others. It could also turn its focus to intermediaries facilitating such divestments—for example, law firms, consultancies, or financial institutions underwriting or advising these transactions. In a more escalatory scenario, China may even consider sanctioning the acquiring firm itself, though Beijing would have to weigh such a move against the cost of cutting its market off from globally integrated firms like BlackRock in the CK Hutchison port deal example.

Catalyzing the clawback

The clawback—and Beijing’s response—will manifest in a range of tactics depending on the asset, corporate stakeholders, and governments in question. For this reason, we do not expect to see a coherent policy articulated around the theme of (re)taking critical assets on national security grounds. Nonetheless, the clawback trend will be a critical geopolitical undercurrent shaping global investment in the coming decade. This a trend that has real momentum in a de-risking climate that will endure well beyond the blunt tactics and rhetoric of the current US administration.

Footnotes

CFIUS jurisdiction broadly excludes greenfield investment, except in cases where located in proximity to specified US government sites, military installations, or critical infrastructure.

“Intentionally materially breaches” applies to transactions initiated before August 13, 2018. See 31 C.F.R. § 800.501(c)(1)(ii)), https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-31/subtitle-B/chapter-VIII/part-800/subpart-E/section-800.501

SAMR has often preferred to informally prohibit deals by delaying its decision past transactions’ close date, thereby de facto scuttling deals.

Article 2 of the Measures defines foreign investment as “direct or indirect investment activities in mainland China (境内) including (…) foreign investors obtaining equity or assets of domestic mainland Chinese enterprises (境内企业) through mergers and acquisitions.” This could potentially exclude transactions involving companies outside of China’s border.