Who’s Buying Whom? COVID-19 and China Cross-Border M&A Trends

The COVID-19 pandemic depressed equity values around the globe, triggering fears of a distressed asset buying spree by Chinese companies. Several months into the pandemic, however, the data tell a different story. There are no signs of a Chinese outbound investment boom. Instead, takeovers are headed in the other direction: into China

The COVID-19 pandemic depressed equity values around the globe, triggering fears across the United States, Europe and Asia of a distressed asset buying spree by Chinese companies. These concerns drove many governments to enact policies – some temporary, some permanent – to shield their companies from Chinese takeovers. Several months into the pandemic, the data tell a different story about cross-border M&A trends. There are no signs of a Chinese outbound investment boom, like the one seen after the global financial crisis a decade ago. Instead, takeovers are headed in the other direction: into China.

This Time Is Different: China’s Investors Are Staying Home

The global financial crisis of 2008/2009 was a catalyst for Chinese outbound investment. PRC companies were insulated from the financial shocks hitting the US and Europe, saw opportunities in falling overseas asset prices, and took advantage of ample liquidity at home and a newly permissive attitude in Beijing toward taking money abroad. That outbound boom cooled after 2016, but the disarray caused by COVID-19 rekindled concerns about another Chinese takeover wave.

In March, we argued that China’s outbound investors are not in a good position to ramp up overseas buying and capitalize on the pandemic in a big way. Compared to the boom years, Chinese companies with global ambitions face a very different environment today, due to the combination of heavy debt loads, tighter domestic liquidity conditions, Beijing’s controls on outbound capital flows and an activated political allergy to Chinese investment abroad.

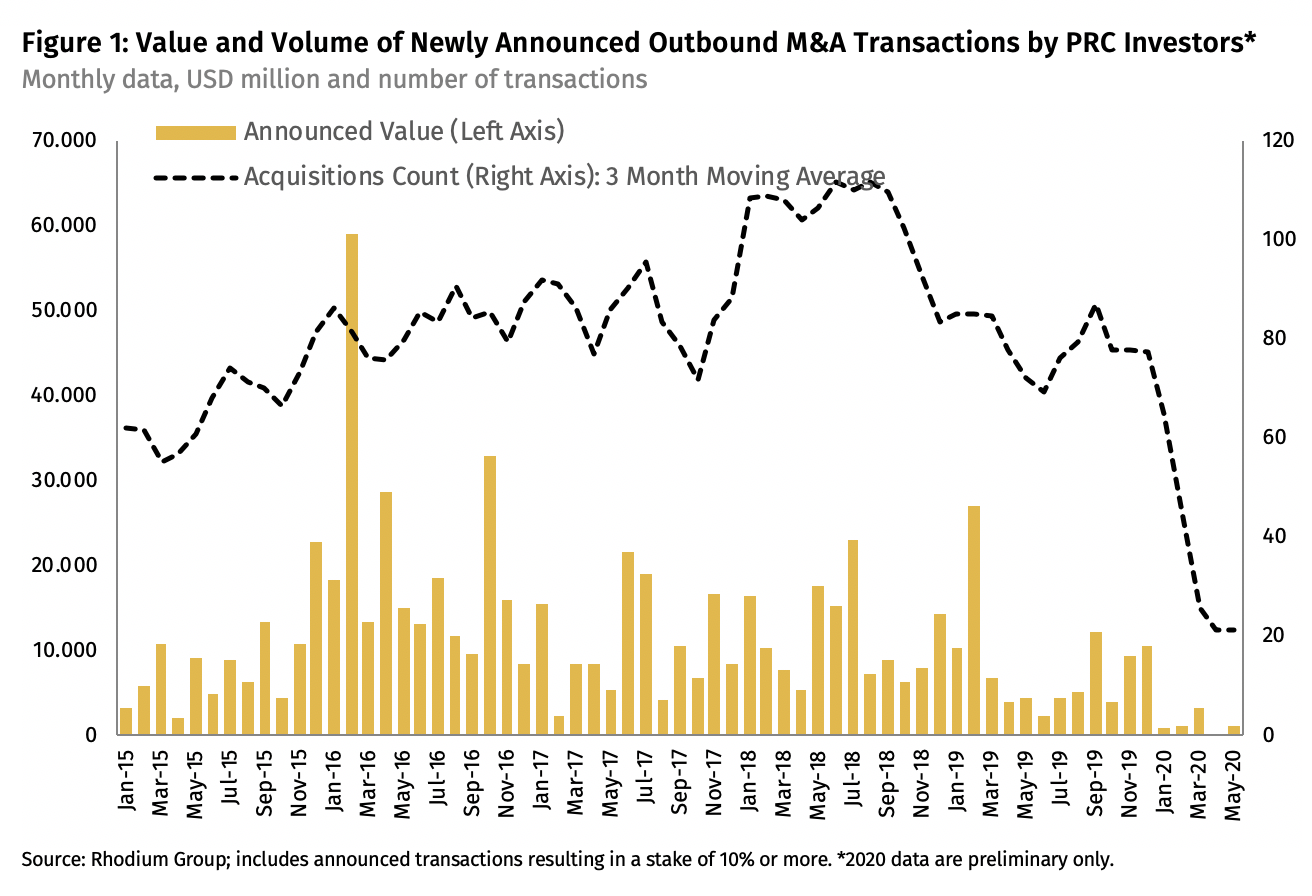

As the second quarter of the year nears a close, the latest data confirm our initial point of view. In the first five months of 2020, Chinese outbound M&A activity collapsed compared to previous years (Figure 1). The number of newly announced transactions dropped from around 90 per month in the 2016-2018 period to barely 30 per month between January-May 2020. Compared to the same period in 2019, new outbound deal making by Chinese firms is down 71% in volume and 88% in value terms. Average monthly transaction values dropped from a peak of more than $20 billion in 2016 to $12 in 2018 and a mere $1.3 billion in 2020. So far this year, all companies in China combined have spent around the same amount on overseas acquisitions as HNA Group did in 2016 on one transaction – its purchase of a 25% stake in Hilton Worldwide Holdings ($6.5 billion).

Knocking at Whose Door? Foreign M&A in China Remains Resilient

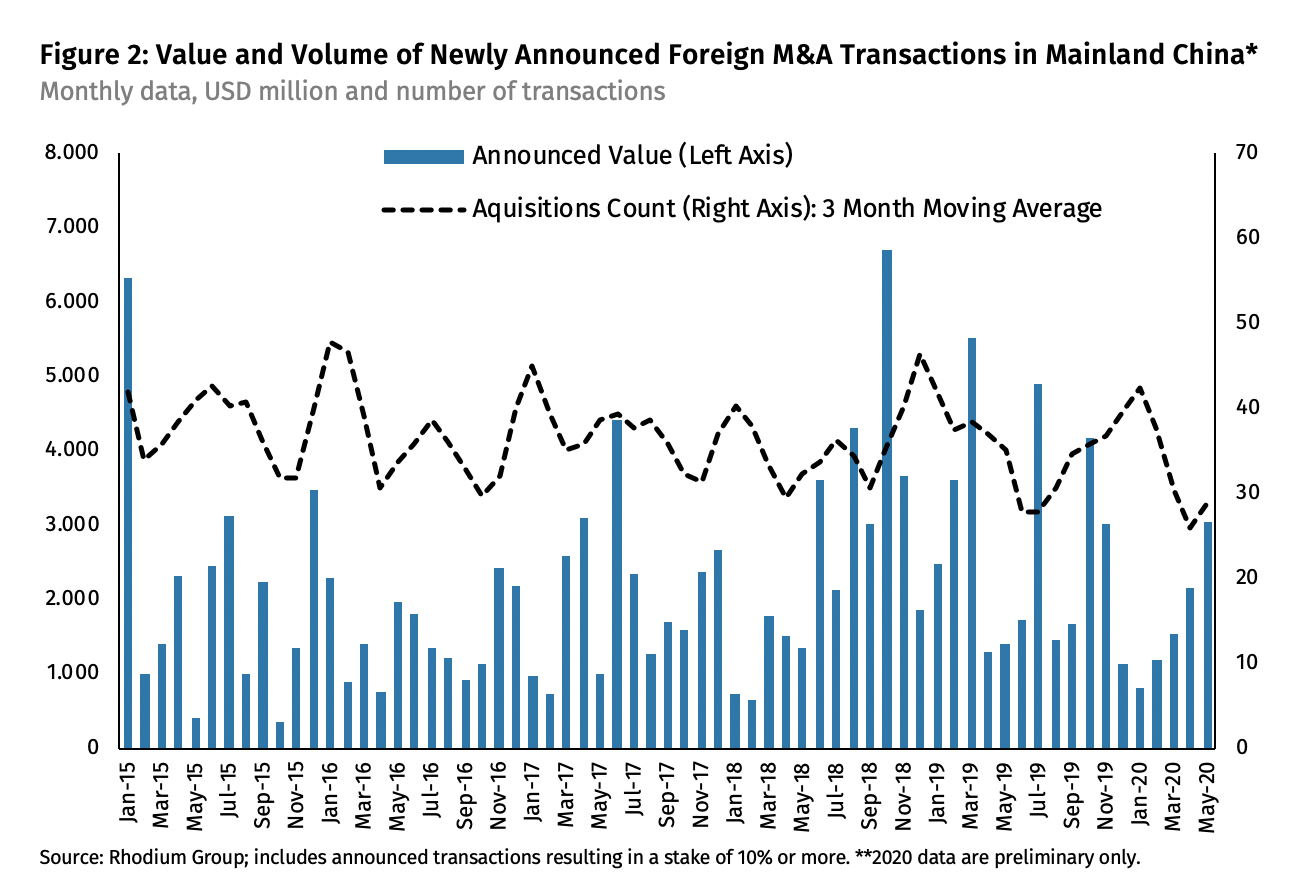

With the spotlight on Chinese outbound investment, few have noticed how resilient foreign M&A in China has been over the past 18 months. For years, FDI in China was dominated by greenfield investments. Over the past decade, foreign M&A activity in China has averaged $20-25 billion per year, a paltry level for an economy worth $13 trillion. Since mid-2018, however, foreign deal making has picked up. In 2019, it reached a 10-year high of $35 billion (Figure 2).

The COVID-19 outbreak has slammed deal-making in both directions this year. But flows into China have picked up every month since January. In the first five months of 2020, foreign M&A into China totaled $9 billion, surpassing Chinese outbound M&A activity in both volume and value terms for the first time in a decade.

Recent deals offer clues about what is driving foreign appetite for Chinese assets. First, Chinese consumption. While consumption has taken a hit – as it has everywhere else – firms are still betting on the secular rise of China’s middle class. One example from 1Q 2020 is Pepsi’s $700 million acquisition of Chinese snack brand Be & Cheery. Second, policy liberalization. Foreign firms are buying shares in their own joint ventures, after China lifted foreign equity thresholds. Volkswagen announced it would take control of its joint venture with Anhui Jianghuai Automotive Group in a $1.1 billion deal, and JP Morgan is acquiring full control of its Chinese mutual fund joint venture for an estimated $1 billion. Third, Chinese firms have matured (through entrepreneurialism, industrial policy and other means) to become leaders in some industries. For the first time, therefore, it is attractive for foreigners to buy technology and industrial assets rather than build from scratch. Volkswagen’s plans to acquire a 26% stake in Chinese battery maker Guoxuan High-Tech for $1.2 billion is a prime example.

Policy Implications

The data points above are just a snapshot of a rapidly changing environment and should be treated as such. But the trends that have emerged over the first five months of 2020 offer some valuable insights for policymakers grappling with China’s role in global cross-border investment flows.

First, reduced FDI flows will be a global reality for some time and China is no exception. The COVID-19 pandemic is dragging on international trade, people flows, and cross-border capital movements. UNCTAD predicts that global FDI flows could drop up to 40% in 2020. China is not an exception and is experiencing diminished capital inflows and outflows.

Second, slowing Chinese outbound investment over the 2017-2020 period shows China’s rise as global investor is not inevitable. China remains vastly under-invested in the world relative to the size of its economy, so it is reasonable to expect Chinese outbound FDI growth to continue. But that does not mean it will happen. China’s future as a global investor depends on two factors: first, the successful implementation of policy reforms at home that have bedeviled leaders in Beijing for years; and second, foreign comfort with Chinese capital, a condition that has shifted starkly to the negative in recent years.

Third, foreign appetite for assets in China will remain robust, despite the chorus of political decoupling and economic re-shoring talk, as long as China represents a sizable share of global growth. Over the past 18 months, we have recorded levels of foreign M&A into China that were not seen in the previous decade. Most of that activity has been driven by American and European firms taking advantage of looser foreign ownership limits or betting on Chinese consumer demand. Over the past century, these firms have continued to do business in challenging locations like Venezuela, Burma and Libya. If China remains an important source of global demand growth, they will exert themselves to invest into that opportunity.

These data points underscore how important it is that OECD policymakers get the balance right between addressing valid security concerns and maintaining openness to foreign capital – both inbound and outbound. Robust investment screening mechanisms exist not just to mitigate national security risks, but to provide the confidence needed to stick to principles of economic liberalism in times of crisis. The pandemic is putting our systems to the test, increasing the role of the state in many economies and accelerating the deployment of investment screening tools to guard against foreign takeovers that could impinge on national security. That is natural and to some extent necessary. But it is important that governments do not go too far and end up undermining the dynamism and competitiveness of open market economies they are trying to protect.