Trade Diversion: Blessing or Curse?

If tariffs remain high, US-China trade flows will be redirected in the medium term: Third countries may find opportunities to serve US demand, but will also face an influx of low-priced Chinese exports.

Regardless of the eventual outcome of US-China trade negotiations, higher trade barriers are likely the new norm, reducing bilateral trade between the world’s two largest economies. In the medium term, that trade will likely be redirected, with third countries backfilling China’s market share in the US and Chinese exporters seeking alternative markets elsewhere. Compared to the last trade war, higher and more volatile tariffs could even end up hobbling global demand, worsening the existing overcapacity crisis. If so, Chinese firms will likely be better positioned than their competitors to expand their share of a shrinking pie by leveraging state support and aggressive pricing. How third countries respond is crucial. An uncoordinated increase in market barriers would still leave manufacturers exposed to Chinese competition in third markets. On the other hand, a coordinated trade bloc partly closed to Chinese goods could divert trade to intra-bloc exchanges and away from Chinese exports. However, such alignment faces major political, technical, and economic obstacles.

Shades of trade diversion

The US effective tariff rate on Chinese goods now stands at 115%, according to IMF estimates as of April 14, and overall US tariffs are at their highest point in over a hundred years. These levels are unsustainable and will likely come down substantially in the weeks or months to come—US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and President Donald Trump have already acknowledged as much. Meanwhile, China announced that it would not increase tariffs further, calling it economically pointless. China might also exempt some essential imports from retaliatory tariffs, just as occurred during the first trade war, even at much lower tariff levels.

Yet even if tariff rates ease, the deeper architecture of the US-China trade relationship is unlikely to revert to the status quo ante. The US is pushing forward with a flurry of bilateral negotiations, spurred by its April 9 decision to suspend reciprocal tariffs on all countries other than China for a 90-day period. These talks are moving quickly and unpredictably, but two basic features of the trade landscape will probably emerge after the dust settles: First, US-China tariffs and politics will remain highly disruptive to bilateral trade flows. Second, US tariffs on China—even if they end up lower than they are today—will likely be very high compared to those on most other trading partners. The result? A comprehensive reshuffling of global trade flows.

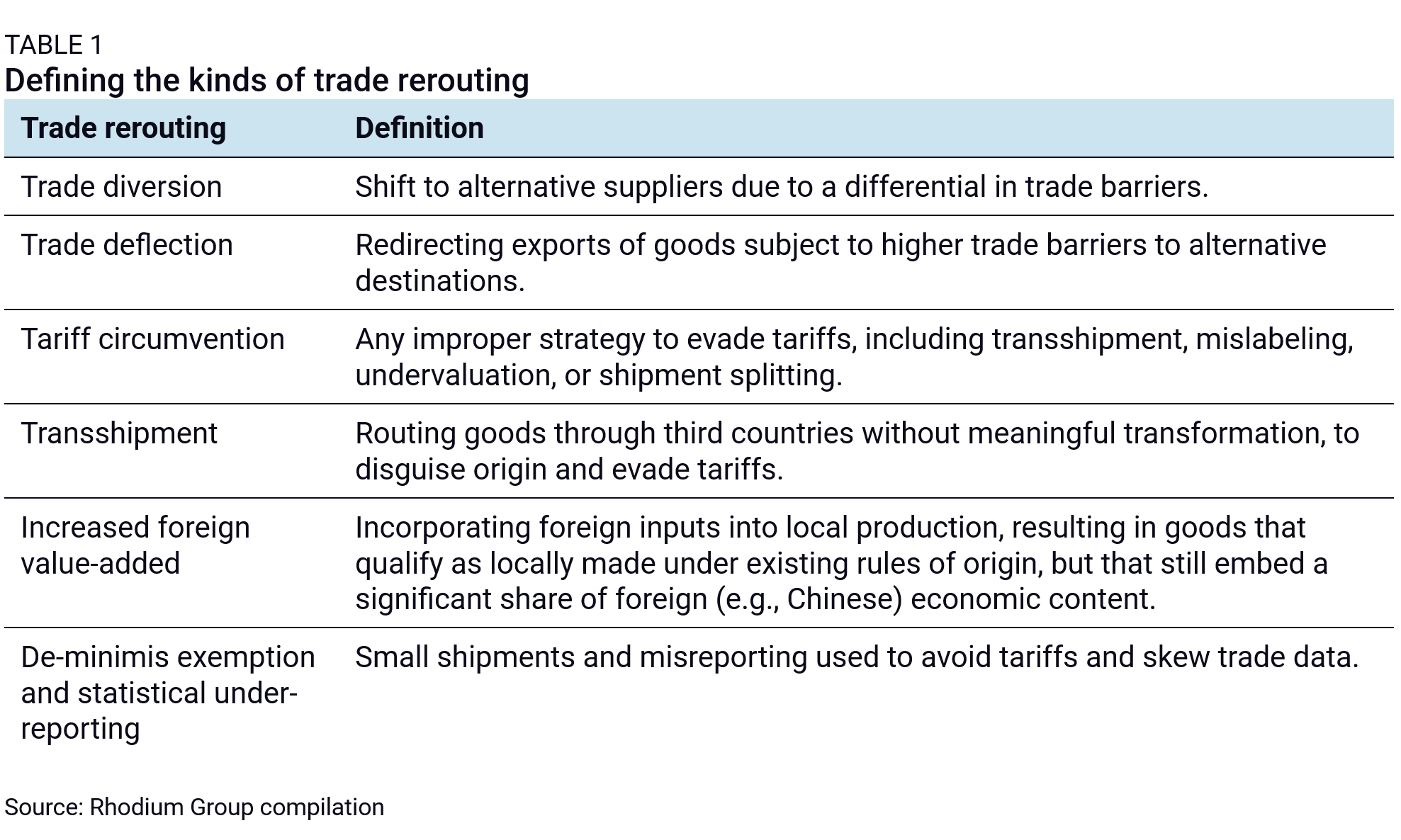

In the 1950s, the economist Jacob Viner laid out a helpful concept to understand this shakeup: Trade diversion is the rerouting of imports from a more efficient external supplier to a less efficient partner within a trade bloc, typically following the creation of a customs union or free trade agreement. Subsequent work introduced the concept of trade deflection, a mirror image of diversion, where exporters respond to trade barriers by redirecting shipments to alternative markets when primary destinations become inaccessible or less profitable (Table 1).

Although both concepts were developed to explain the effects of preferential liberalization, they apply just as well in the context of a trade war. In this case, US demand once reliant on Chinese supply must now be met by other partners, while Chinese goods that once moved into the US are being rerouted elsewhere. The central question is not whether this reshuffling will occur, but who will benefit and who will lose out.

Lessons from the first trade war

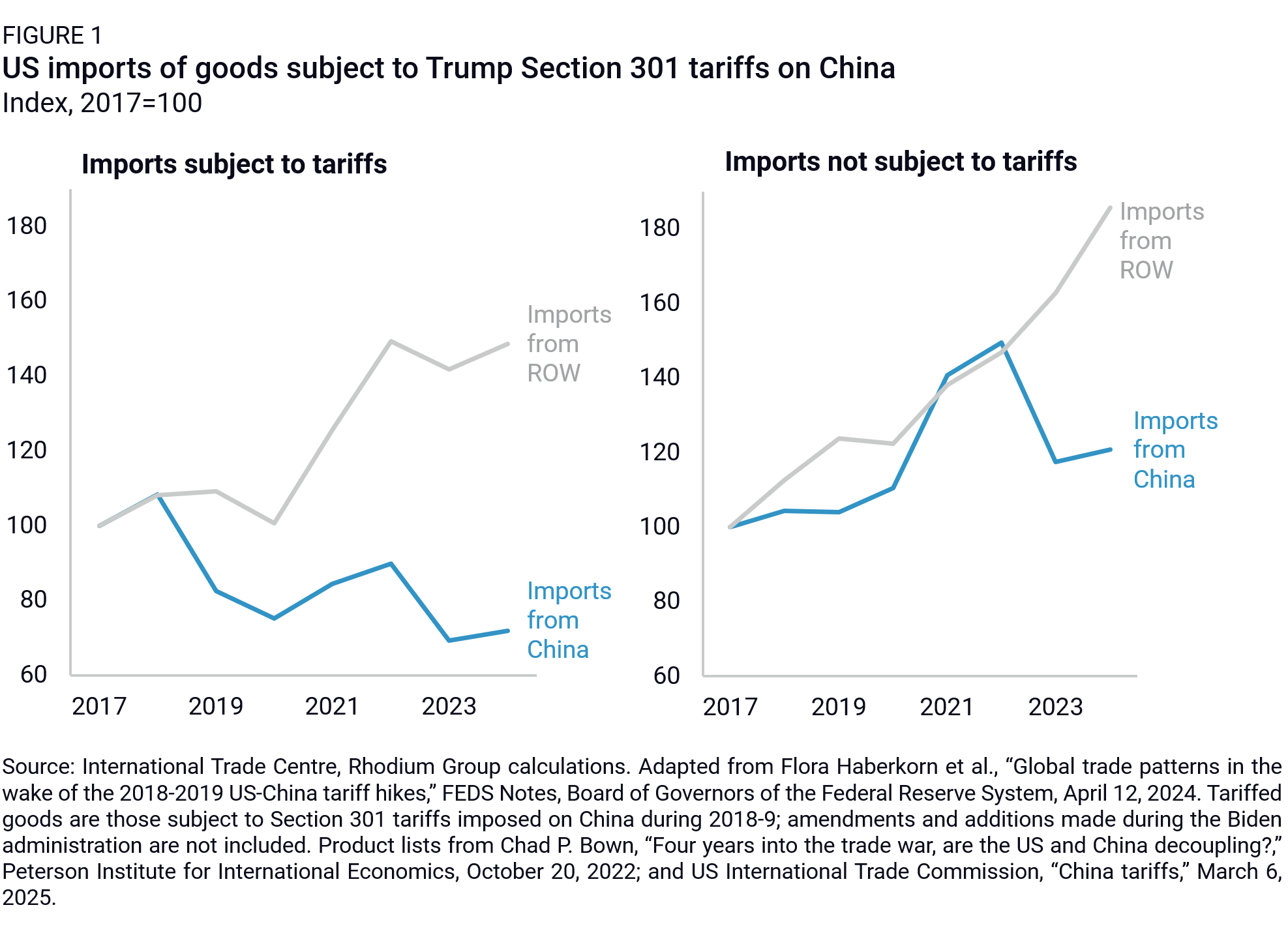

To understand how this US-China trade war will reshape global trade, the previous one is a useful guide. At first glance, the 2018 round of US tariffs on Chinese goods—ranging from 7.5% to 25% on approximately two-thirds of imports from China—did appear to significantly redirect trade. Between 2017 and 2024, China’s share of US imports dropped from 21.9% to 13.8%. By 2024, US imports of tariffed Chinese goods were 28% below 2017 levels, while imports of all other goods rose by 21% (Figure 1).

Yet the underlying picture is more complicated. Despite substantial tariffs, the US still recorded $439 billion in direct imports from China in 2024, second only to Mexico. Most Chinese imports did not disappear—they simply became more expensive. Near-complete tariff passthrough raised prices for US firms and consumers, and retailers absorbed much of the increase.

In addition, trade circumvention likely led to understating the true extent of US-China trade. De minimis shipments and statistical misreporting have obscured the degree of US reliance on Chinese imports. The widening gap between Chinese export records and US import figures highlights this bias: While the US data shows US imports from China falling by 18% between 2018 and 2024, Chinese data shows Chinese exports to the US growing by 9%. Transshipment, Chinese goods transiting through third countries before being re-exported to the US, further contributed to the continued reliance on Chinese goods.

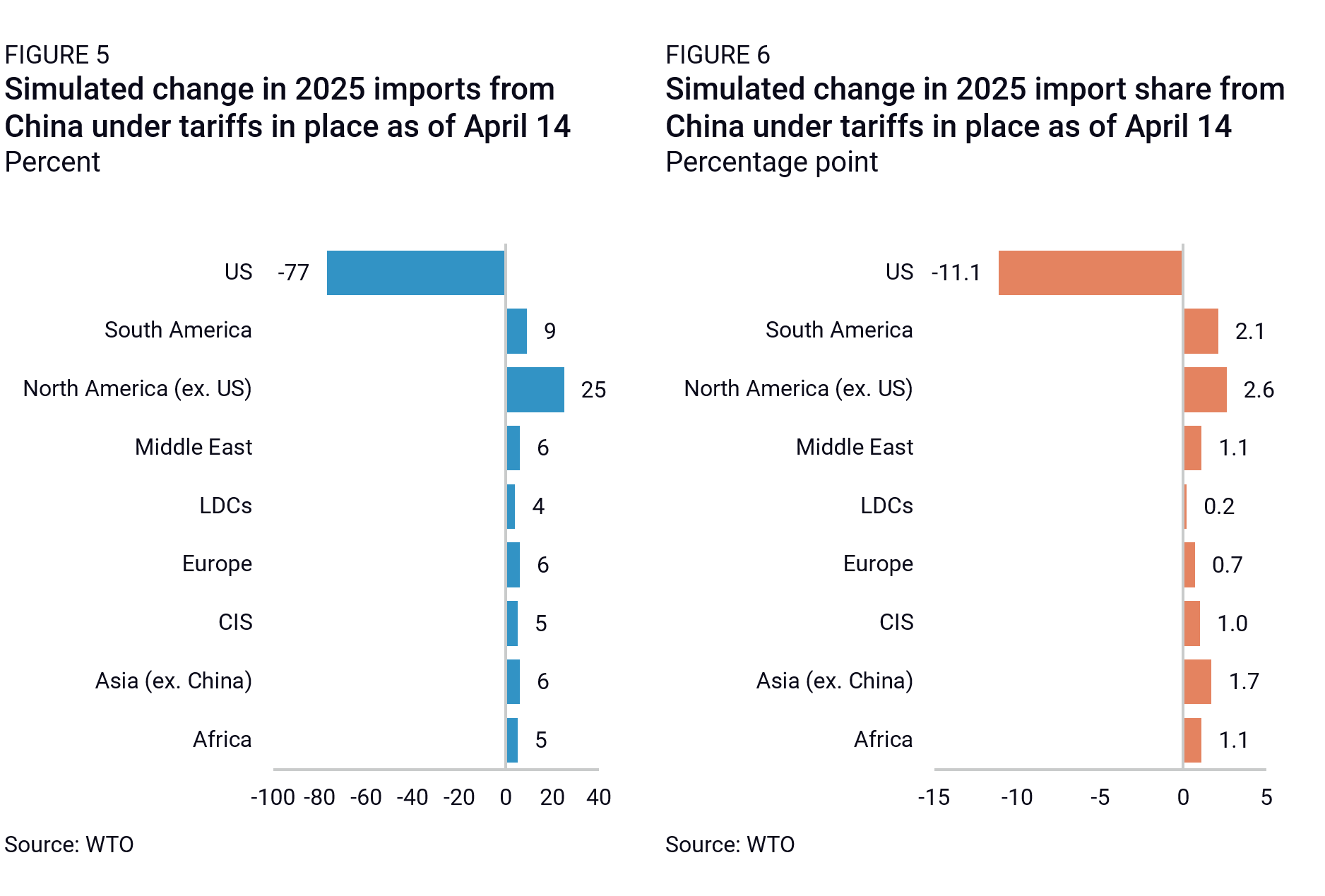

What should one expect this time around? Given much higher tariffs, US consumers and firms are less likely to be willing or able to absorb cost increases. Meanwhile, Chinese exporters have little room left to meaningfully offset tariffs with either price cuts or currency depreciation. The result will be a deep and rapid decline in direct US sourcing from China. Already, many US retailers are reporting canceled import contracts and are warning of a sharp drop-off in cargo import volumes. To convey a sense on the magnitude, in its latest Global Trade Outlook, the World Trade Organization (WTO) estimated a 77% decline in US imports from China in 2025 and an 11.1 percentage point reduction in China’s share of US imports, based on simulations of policies in place as April 14.

Under-reporting imports from China will also be more attractive than during the first round of tariffs, and trade data could become increasingly misleading. While the Trump administration has ended the de-minimis exemption for packages coming from China effective May 2, enforcement will also prove difficult. Exporters are nimble and can adapt by rerouting through transshipment hubs like Cambodia, or by undervaluing shipments to reduce their declared customs burden. As a result, official import data may significantly understate actual flows in the coming months.

But circumvention tactics can only partially offset the effects of tariffs and Chinese exports to the US are still likely to fall very significantly. The Trump administration is aware of the challenges associated with transshipment and has begun securing offers of cooperation from key transit hubs, such as Vietnam. New AI and high-tech tools to better detect Chinese content at the border may also make enforcement more effective over time. Customs enforcement will be critical to watch in assessing the true impact of the new tariff regime in the coming months and years.

Who wins and who loses in the reshuffle?

As the dust settles in the coming years, the winners and losers of this global trade realignment will start to take shape. At the outset of the first trade war, many countries hoped to backfill China’s market share in the US. Early modeling and analysis identified the EU as a possible beneficiary because its existing industrial structure appeared well-suited to capture market share in sectors targeted by tariffs. However, the way the trade war unfolded ultimately failed to deliver the expected opportunities for most countries.

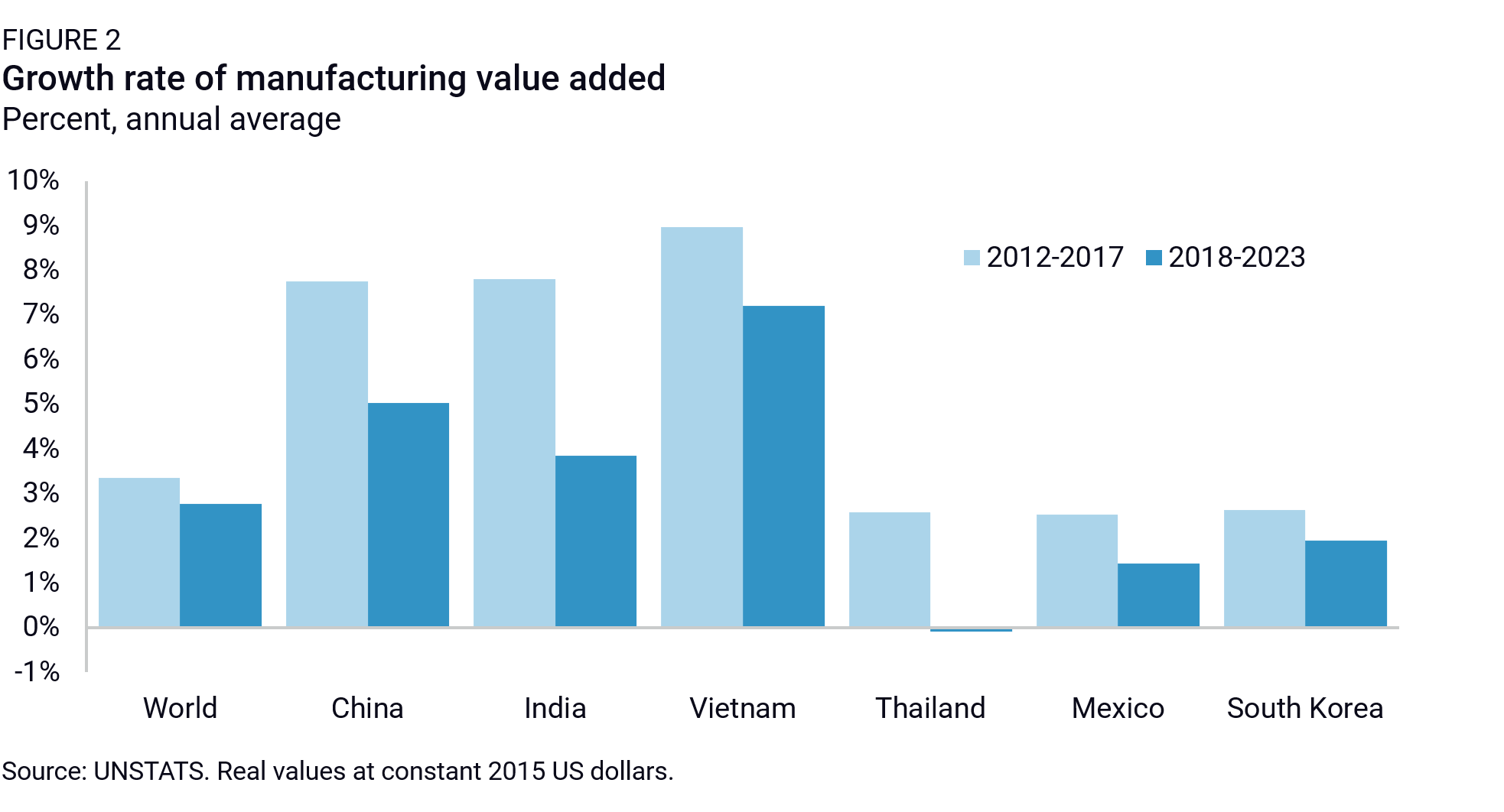

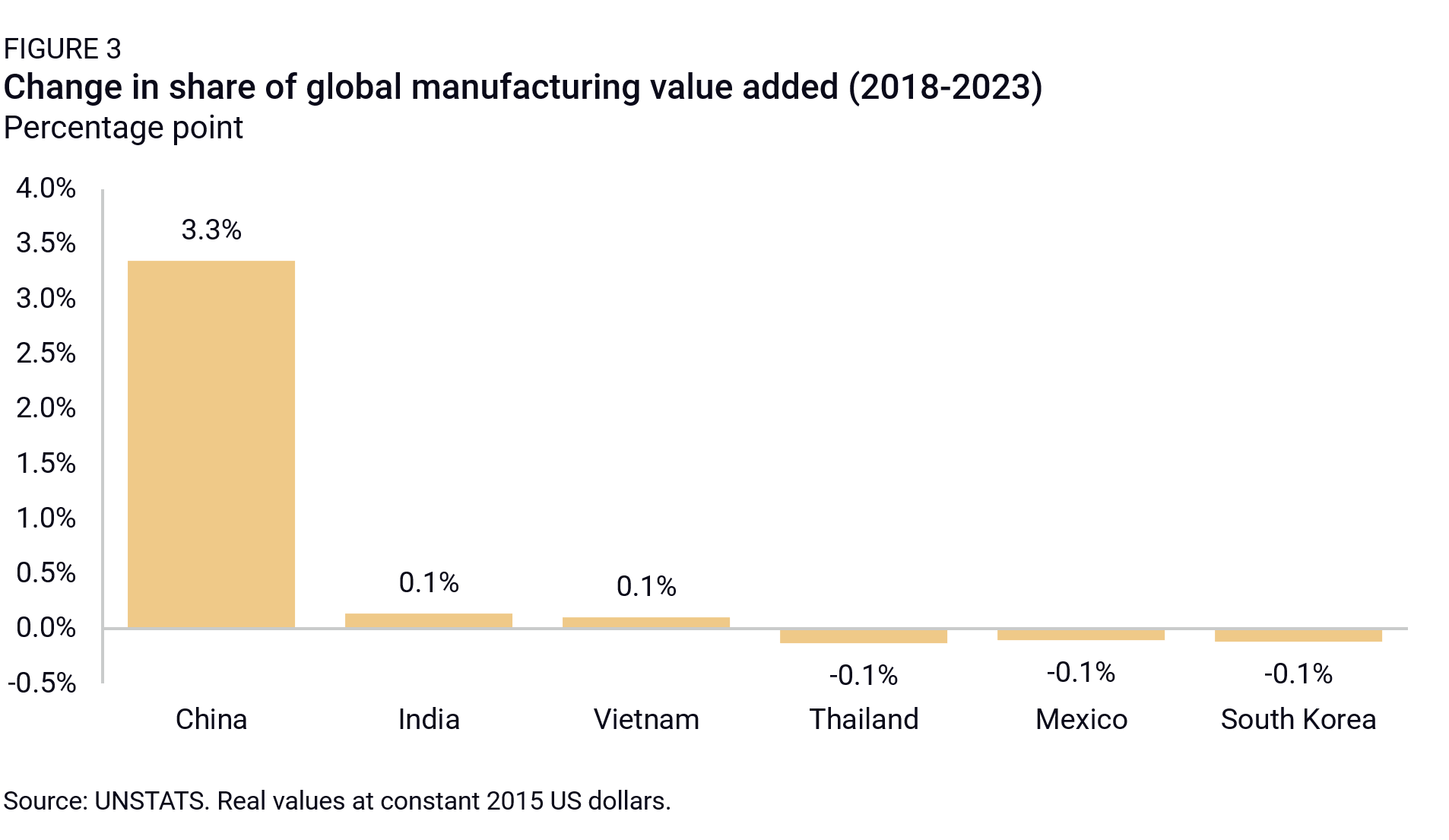

While 2018-19 tariffs led to significant trade diversion (the redirection of US imports of affected goods from China to other trading partners), China remained the global manufacturing powerhouse. China’s share of global manufacturing value added increased by a striking 3.3 percentage points, while the five countries that grew their share of US imports the most (Vietnam, Mexico, India, Thailand, and South Korea)1 collectively saw their share of global manufacturing value added diminish by 0.1 percentage point (Figures 2 and 3).

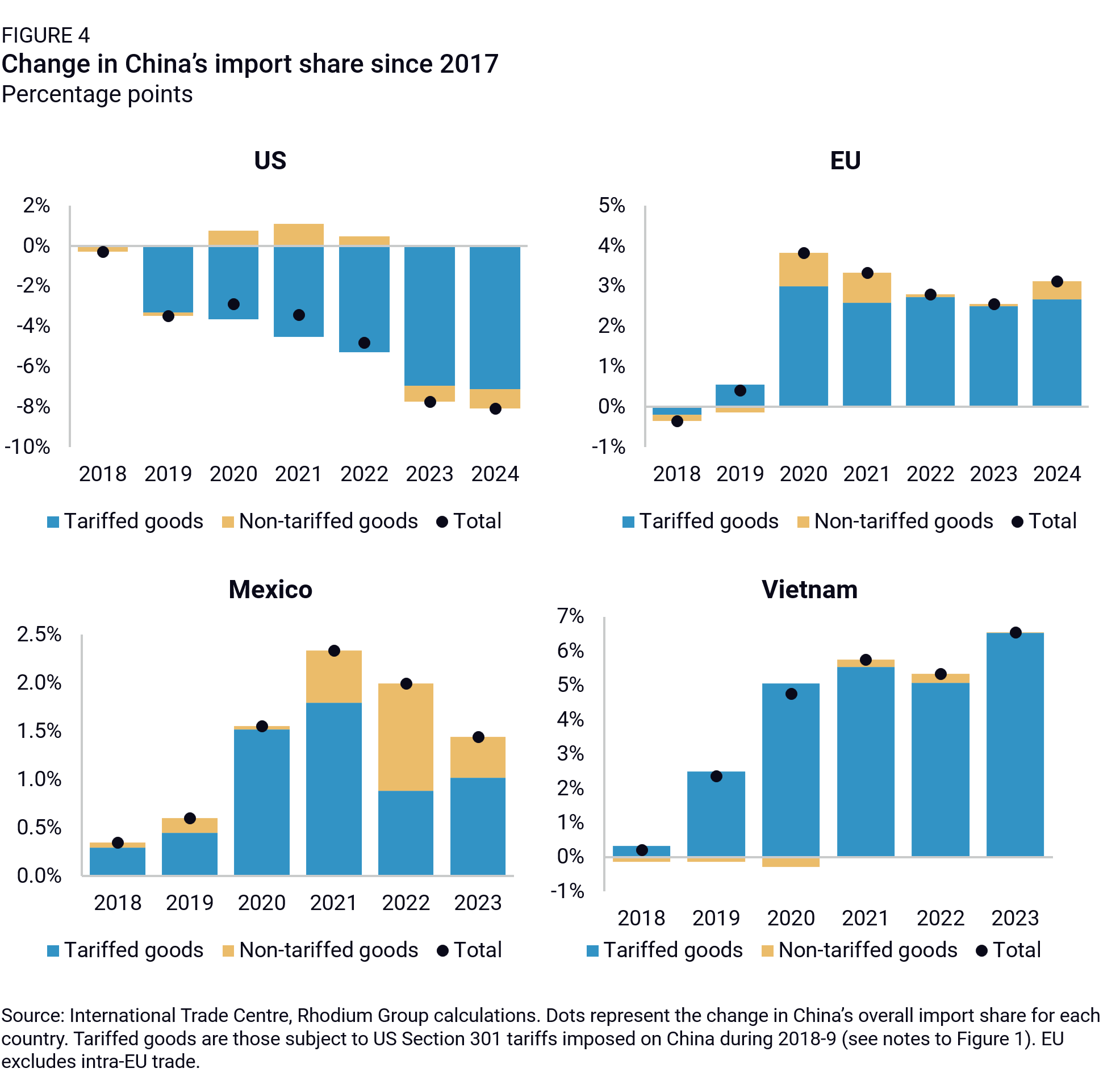

Of course, not all of this shift is because of the trade war: factors such as pandemic-era production disruptions and overcapacity also played an important role. But trade redirection contributed significantly to China’s continued global competitiveness. Part of the explanation lies in trade deflection: As Vietnam, Mexico, India, and other countries shifted their production of tariffed goods toward supplying the US market, China stepped in to fill the gaps they left behind in other destinations. Overall, as the share of US imports from China declined in tariffed goods, China’s import shares in the rest of the world increased in those same goods (Figure 4). For products hit by US tariffs, the percentage of Chinese exports absorbed by the rest of the G20 rose from 43.4% in 2017 to 52.3% in 2023.

Another key factor is the deepening linkages between Chinese firms and third-country exports—either via Chinese intermediate inputs in locally produced goods or direct investments by Chinese firms in foreign manufacturing. These patterns have been especially pronounced in alternative export hubs, notably ASEAN and Mexico, and are reflected in increasing amounts of Chinese value-added content in US imports from them. Chinese manufacturing investment in ASEAN has accelerated rapidly, particularly in sectors such as clean technology, where Chinese firms are building production bases closer to key consumer markets.

What should one expect this time around? Trade diversion is likely to be more significant in this trade war, given that the tariff differential between China and other countries is now wider. While the Trump administration is betting on a revival of US manufacturing to fill the gap, this is unlikely to occur at the scale or speed needed to replace Chinese goods. As a result, a large share of US demand will inevitably be redirected toward other suppliers, creating new opportunities for countries well-positioned to step in. Which countries can benefit will depend on their tariff rates relative to China’s, economic fundamentals, human resources, and logistical infrastructure, as well as policy responses. Most of these shifts will play out over the medium term, as supply chains, sourcing contracts, and trade policies adjust over the next two to three years.

Trade deflection is also poised to rise sharply. Again using the WTO’s latest Global Trade Outlook, Chinese exports are expected to increase everywhere except the US in 2025—with projected growth of 6% in Europe and 25% in Mexico and Canada (Figure 5). China’s share of regional imports is also set to rise, by 0.7 percentage points in Europe and 2.6 points in Canada and Mexico (Figure 6). Those countries, but also other emerging markets, will likely absorb more Chinese exports. According to a survey by the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade, 75% of 1,100 surveyed Chinese exporters intend to expand into emerging markets to compensate for shrinking exports to the US. This suggests a rapidly growing global dependence on Chinese goods, even as many governments seek to diversify away from China.

Both trade diversion and trade deflection, however, could be significantly challenged by the US administration’s evolving stance toward Chinese content embedded in third-country exports. An April 2025 report to the president highlighted revising rules of origin (RO) to limit the deepening of Chinese value added in foreign production. ROs are already reportedly the subject of negotiations with key trading partners. The America First Investment Policy released in February 2025 also signaled a hardline approach toward Chinese-owned investments in the United States—an approach that could extend to limiting Chinese-controlled activities in third countries that wish to maintain preferential access to the US market. For example, Washington could demand ASEAN and other partner countries reduce Chinese content and linkages in their manufacturing operations. This would make it much harder for Chinese goods to be used as intermediate inputs, constraining Beijing’s ability to offset US tariffs by expanding its footprint in alternative destinations. Beijing is already attempting to preempt this outcome, calling on countries not to strike deals with the US at China’s expense.

Overcapacity on steroids

Another major factor in China’s growing share of global manufacturing in the past few years has been the country’s overcapacity crisis. It pushed surplus goods into global markets and drove out foreign producers. That overcapacity has not eased—in many sectors, it has only worsened. Now, layered on top of it, the world faces a new overcapacity shock—this time not triggered by Chinese stimulus, but by a sharp contraction in US demand for Chinese goods. Tariffs could hit US domestic demand in a variety of ways, including declining consumer confidence and purchasing power, negative wealth effects, rising costs, policy uncertainty for businesses and investors, and the possibility of higher-for-longer interest rates. These risks would be even more pronounced if the original reciprocal tariffs are imposed on key alternative suppliers such as ASEAN countries in July, amplifying inflationary pressures and further depressing demand. Moreover, if the US tips into recession, the resulting contraction in American consumption would spill over internationally, causing demand to plunge elsewhere and deepening the overcapacity problem.

While the magnitude and duration of these impacts are deeply uncertain, economists are broadly marking down their expectations for near-term US growth. The Bloomberg survey median forecast for 2025 US real GDP growth has come down by nearly a full percentage point since February, sinking to 1.4% in April. The IMF made a downward forecast revision of similar size in its April 2025 World Economic Outlook, from 2.7% to 1.8%.2 Moreover, the IMF warned that weaker US private consumption and investment will have negative spillovers worldwide, particularly hurting export-oriented economies. Mexico, highly exposed through its trade links to the US, saw an especially large 1.7 percentage point cut to its 2025 growth outlook.

In that scenario, Chinese firms in already overcapacity-driven sectors would likely double down on a familiar strategy: aggressive price-cutting to defend sales volumes and expand global market share. This time, they will do so with much thinner margins. The current trade war comes on the heels of a previous overcapacity cycle that left manufacturers with historically low profitability: The sector’s profit-to-sales ratio fell to 4.5% in 2024, down from 5.9% in 2018. Fiscal revenues and bank profitability have also weakened, meaning firms may have less room to absorb further price cuts and more bankruptcies could follow. Still, China’s politically-driven credit system, despite its inefficiencies, will likely keep key exporters afloat longer than would be possible elsewhere. Meanwhile, a depreciating RMB would further sharpen Chinese firms’ cost advantage against producers in other major economies, whose currencies have so far broadly appreciated against the dollar. As a result, producers in third countries will likely face intensified competition from underpriced Chinese goods, both in their domestic markets and in overseas markets, eroding their competitiveness on multiple fronts.

Third countries’ reactions

The response of third countries will be decisive in shaping future patterns of trade diversion and deflection. Some countries will likely adopt a mix of unilateral trade defenses, such as anti-dumping and safeguard actions. Many already do: In 2024, overcapacity spillovers prompted countries around the world to launch an unprecedented 198 anti-dumping and countervailing duty investigations. This includes the EU, which launched a record 20 cases last year.

So far, however, third country reactions have been fairly uncoordinated. Each economy has limited capacity to tackle all Chinese trade deflection and will likely concentrate on protecting a few sensitive sectors, leaving plenty of less strategic sectors open to Chinese competition. Some countries will likely aim to avoid direct confrontation with China and respond only indirectly, like via non-tariff barriers, or not at all. Without coordinated global action, unilateral trade defense efforts will offer only limited relief, as diverted Chinese exports and spillover from Chinese overcapacity will pressure producers in third markets. This will be particularly challenging for export-oriented economies that compete with Chinese firms overseas on a range of similar products. The EU, but also ASEAN countries, which are among the most dependent on exports for their growth, will likely be among the most affected. For a highly open economy like Vietnam, for example, exports are worth as much as 80% of GDP, with textile exports alone accounting for 10% of GDP. If Vietnam’s export destinations do not raise trade barriers, the country risks facing intense competition from Chinese exporters and losing crucial export revenues as a result.

A key question here is how much China factors into Washington’s trade negotiations with its partners, and in particular whether the US pressures partners into coordinated trade actions against China. While the Trump administration’s commitment to this strategy is unclear, if it does apply strong pressure during trade talks, this could signal an effort to build a new trade bloc less dependent on China. This redesigned trade bloc could be characterized as an effort to wall off China’s overwhelming market power—built on the back of uniquely large and systemic market distortions—in order to prevent further de-industrialization in third countries. It could also be driven by a range of security-minded measures, in which members accept the heavy economic costs of collectively reducing Chinese market access in in certain sectors in return for reducing the potential for disruption in critical products and infrastructure.

This course of action would cause large global efficiency losses and supply chain disruptions, as less cost-competitive firms from within the bloc would step in to fill the gap, raising prices globally and creating redundancies. However, a shift to less efficient exporters isn’t always a loss: Economists like Richard Lipsey and Harry Johnson showed that under the right conditions, customs unions could boost welfare by creating new opportunities for trade within the group. Whether economies in such a bloc would stand to benefit would depend heavily on its scale and coherence. Countries would have to weigh whether revenues from capturing market share previously held by Chinese suppliers would outweigh the risks and losses from potential Chinese retaliation via trade restrictions, lost market access, or disrupted supply chains.

What to watch for

Trade diversion patterns will be shaped most impactfully by the difference between US tariffs on China and on other countries. Beyond trade negotiation outcomes, several key variables will affect how trade patterns are reshuffled in the medium term.

First is the extent and pace of damage to the US economy. US economic weakness will not only shape the Trump administration’s political ability to sustain its tariff strategy, but will also heavily influence global demand in the months and years ahead. Already, leading indicators are flashing red, including plunging consumer sentiment, escalating inflation expectations, downbeat business surveys, severe economic policy uncertainty, and “yippy” bond markets. April data on prices, employment, imports, and consumer spending will offer early indications of the fallout.

Second is Beijing’s economic policy response. A meaningful demand-side stimulus in China could alleviate global overcapacity pressures, by expanding domestic demand to absorb a larger share of output. The trade war shock could possibly provide some political cover for Beijing to make hard, but necessary, choices on economic reform: A recent People’s Daily commentary even hinted at the possibility. So far, however, Beijing’s rhetorical pivot toward domestic consumption, which has intensified since late 2024, has been accompanied by only modest concrete measures. As we explained earlier this year, boosting consumption would require deep restructuring of China’s fiscal and financial system, a shift that remains unlikely in the near term.

Last is Washington’s ability to design a clear strategy toward China and restore and rebuild trust as a coalition leader—trust that has been strained by unpredictable and shifting policies. As a result, key US trading partners are already hedging their positions. Beijing will actively push back against any effort to isolate China—and will likely succeed in many cases.

In this context, while a coordinated bloc-based trade system excluding China is theoretically possible, it remains unlikely. The most probable outcome over the next few years is a more fragmented global trading system, marked by uncoordinated responses, a proliferation of trade defenses, and increasingly complex patterns of diversion and deflection. Countries will likely respond in piecemeal fashion, focused on shielding a few strategic sectors, while Chinese firms expand their global market share.

Footnotes

Taiwan, which also saw its share of US imports grow very fast, is excluded for lack of data.

The baseline projections in the IMF’s April 2025 World Economic reflect the Fund’s “reference forecast” based on policies announced as of April 4. This does not reflect the 90-day pause of US reciprocal tariffs announced on April 9, nor does it include the full set of US-China tariff escalation and retaliation that followed the April 2 reciprocal tariff announcement.