The Urge to Merge: Streamlining US Sanction Lists Targeting China

As efforts to harmonize US blacklists expand, we examine scenarios under a potential Harris or Trump administration and measure the impact on Chinese firms.

Over the past decade, sanctions and entity listings targeting China have ballooned across federal agencies as policymakers attempt to cover a range of national security risks, from Chinese military modernization to human rights abuses and cyber vulnerabilities. But as the regulatory net expands, the holes are growing more visible. This has spurred some members of Congress to call for harmonizing different lists to ensure designated “bad actors” are wholly restricted from US tech, market access, capital, and know-how.

In this note, we examine scenarios for list streamlining to assess their impact on Chinese firms, their likelihood under a Harris vs. Trump presidency, and what investors need to watch ahead. We find that:

- A potential Harris administration is likely to continue the current administration’s incremental steps toward streamlining lists, with Commerce and Treasury in the lead. This includes a significant evolution in export controls covering “support” for military, intelligence, and security end-users.

- A potential Trump 2.0 administration would likely favor a blunter approach, and a revived role for the Pentagon in list-making.

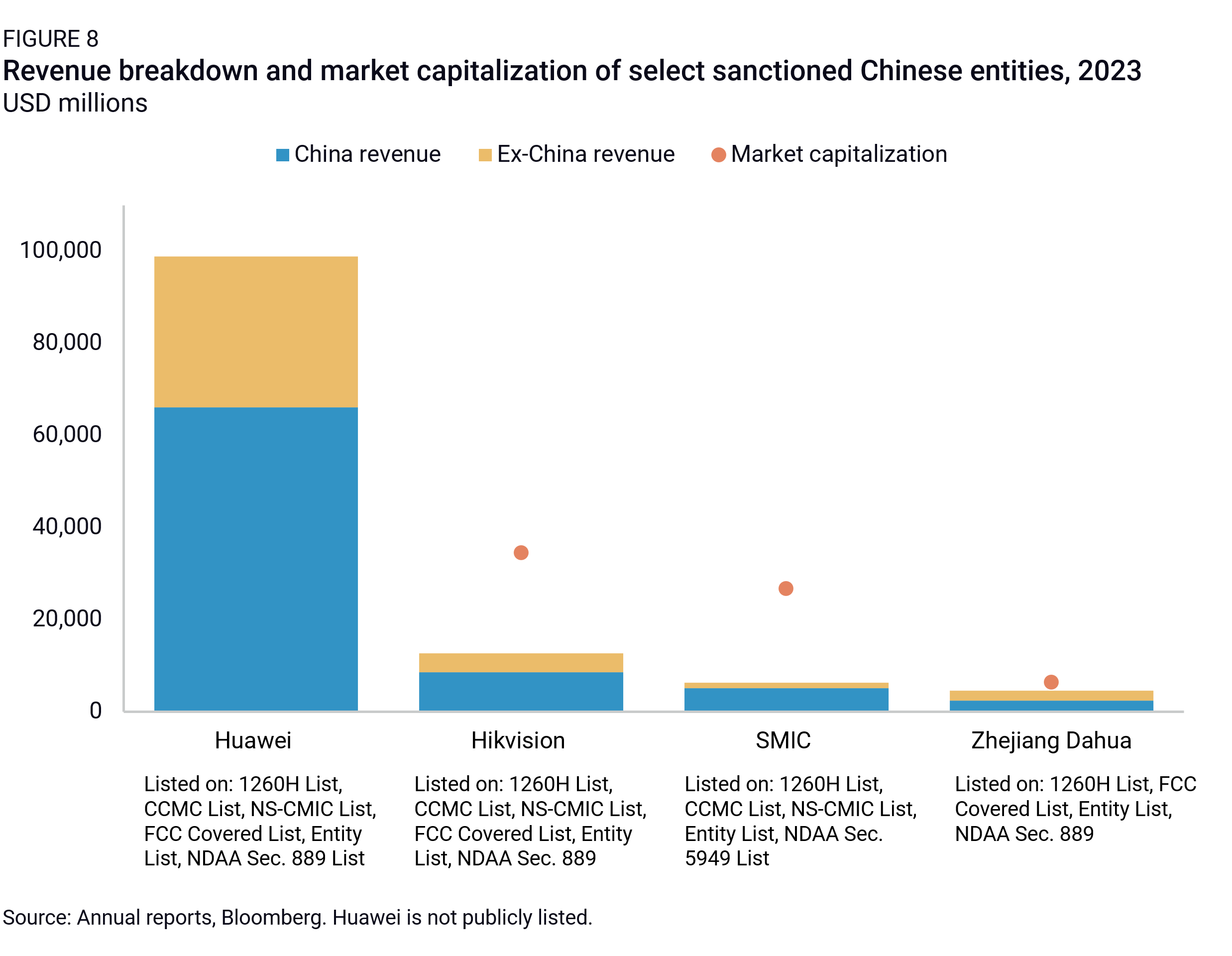

- In a maximalist scenario of full blocking sanctions applied to targets such as Huawei, SMIC, Hikvision, or Zhejiang Dahua, at least $40.2 billion in ex-China revenue and up to $67.5 billion in aggregate market cap could be at risk. Such a long-arm move would create significant global spillovers.

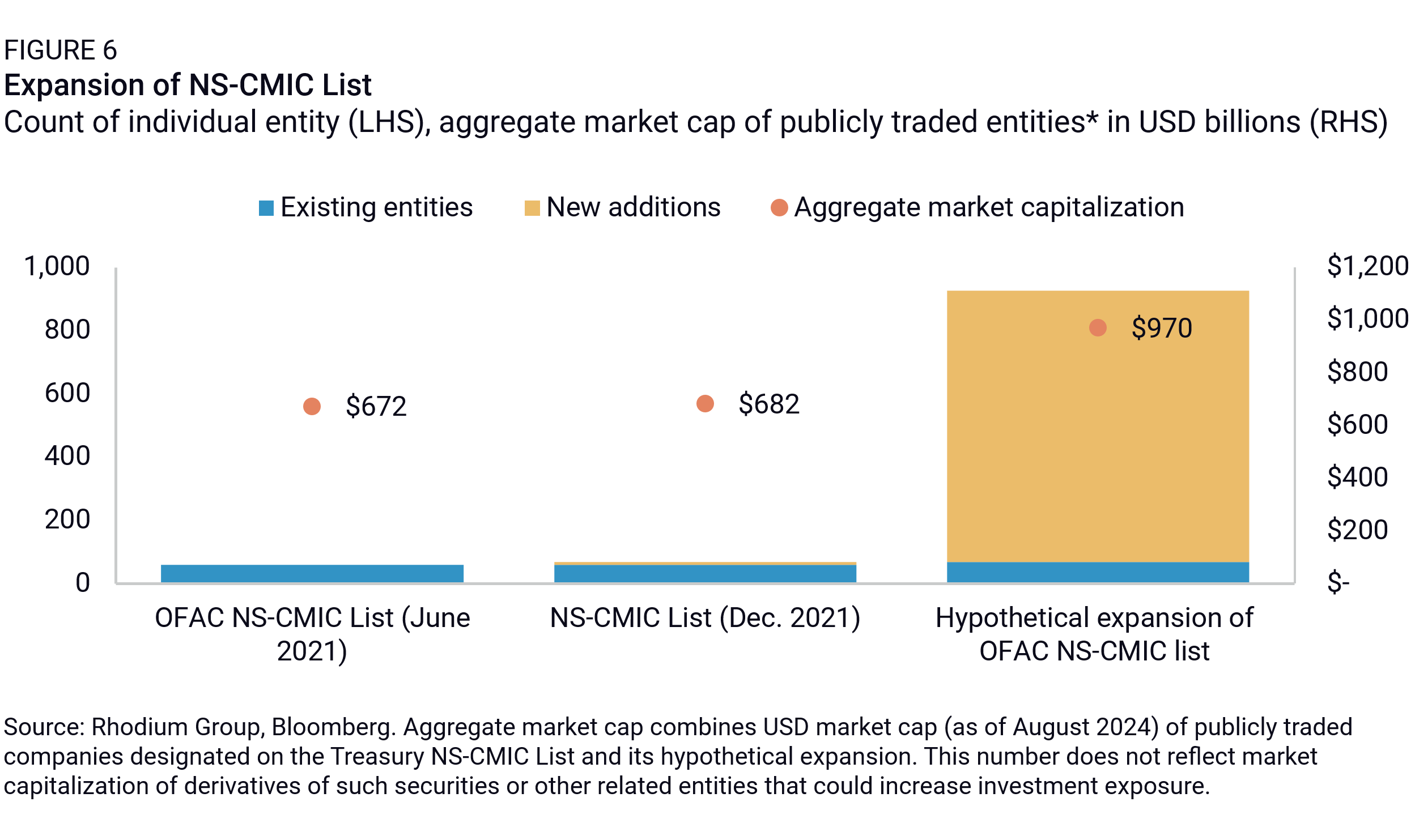

- An expansion of the Treasury NS-CMIC List, which restricts US persons from trading in securities of listed entities, is among the likeliest options. If Chinese entities on other US sanctions and red-flag lists were added, the NS-CMIC List could expand from its current 68 entities to 927 entities, representing a combined market capitalization value of $970 billion.

- If key government procurement lists were pooled together, more than 100 entities, including major Chinese semiconductor and biotech companies, would be covered. A procurement priority list could be the gateway to further restrictions.

From list proliferation to harmonization

Over the past decade, US regulators have employed more than ten different lists to target Chinese firms deemed harmful to US interests (Table 1). By July 2024, more than 1,000 Chinese firms had been designated under US sanctions and red-flag lists (Figure 1).

With Washington increasingly focused on competition with China, many legislators have pointed out holes in the expanding regulatory net. The arguments fall into three main prongs:

- Resolve contradictions: If a Chinese firm has been labeled a “military company” via the DOD’s 1260H List, should it also be subject to export controls via the Commerce BIS Entity List to prevent US technology from enabling China’s military? And if a company is already being denied US technology (BIS Entity List), has been designated a military company (DOD 1260H), or uses forced labor (UFLPA Entity List), then should that company also be denied access to US capital (Treasury NS-CMIC)?

- Whack-em-all vs. whack-a-mole: Companies will likely create shell firms and spinoffs to evade sanctions, and efforts in Washington to track those movements and update sanctions listings are laborious. An increasing number of lawmakers have called for lists to automatically extend to entities’ subsidiaries, affiliates, and successors.

- Expanding the ‘small yard’: The Treasury Department is close to finalizing new rules restricting outbound investment in a core set of force-multiplying technologies (semiconductors, AI, and quantum). Treasury’s attempt to keep the scope of the new regulation narrow has fueled a larger debate in Congress on whether to cover more ground (for example, by taking an entity-based approach to US capital restrictions, including additions to the Treasury NS-CMIC List or even full blocking Treasury SDN sanctions). This impulse by Congress to cover more ground has also spawned new preemptive categories, such as “biotech entities of concern” (BIOSECURE Act) to preemptively target Chinese firms that are currently outside of Treasury’s outbound rule scope.

Pardon our dust: Lists under construction

While elements of these arguments may hold merit, the reality of simply streamlining red-flag and sanctions lists is much more complex. For example, government agencies have varying levels of rigor and criteria for making designations. This can come down to the resources any one agency has to do their homework on the firms in question and analyze spillover effects before making new designations. Resourcing this effort, not to mention coordination among government agencies, can be trying to say the least. For these reasons, the Biden administration has resisted a blunt approach of harmonizing lists and has instead taken incremental steps to rationalize the debate.

The Biden administration saw the limits of an inherently reactive approach to entity-based sanctions. This is, in part, what led the US to embrace preemptive measures applied to an entire geography—consider China-wide semiconductor export controls and import restrictions scoped to certain goods made in Xinjiang. Even as entity listings have continued in parallel to these broader controls during the Biden administration (Figure 1), some lists have gone dormant. For example, a BIS list for military end-users has languished while the focus has been on the BIS Entity List. Republican lawmakers have often lamented Treasury’s inaction in expanding the Treasury NS-CMIC List and claim that Treasury and Commerce officials have sidelined the DOD in identifying Chinese companies that are harmful to US national security. More broadly, lawmakers are divided over whether a sector-based or entity-based approach to sanctions is the optimal path to regulating trade and investment with China.

The Biden administration is striking a balance in the debate over sector- versus entity-based sanctions. For example, in Treasury’s updated proposed rules for outbound investment screening, a prohibition category was added for investments in semiconductors, AI, and quantum if a transaction also involves an entity on certain sanctions lists (Treasury SDN List, BIS Entity List, BIS MEU List, Treasury NS-CMIC List, and State Foreign Terrorist Organization List.)

The Biden administration is also making significant housekeeping moves that set the stage for a new wave of entity listings. On July 29, Commerce BIS proposed a new rule to both streamline lists and expand designations for entity listings (Table 3). For example, BIS wants to do away with the blanket “military-intelligence” designation and has proposed instead to create footnote designations for a) military end-users, b) military support end-users, c) intelligence end-users, and d) foreign security end-users on the BIS Entity List. BIS also intends to consolidate the moribund Military End-User List with the BIS Entity List. Certain footnote designations also trigger restrictions on US persons tied to “support” for military, intelligence, or security activities, thereby raising the compliance burden for MNCs trying to screen for linkages to listed entities. Altogether, these moves enable BIS to expand its scope to capture more entities operating in the nebulous “support” function, more precisely justify new entity listings, and apply various degrees of restrictions depending on which footnote designation is triggered.

In selectively marrying list-based sanctions with sector-based measures and laying the groundwork for more expansive export controls with new footnote designations for end-use, the US administration is being responsive to congressional appeals for a stronger entity-based approach to China measures. At the same time, the US administration is trying to ensure that there is a robust regulatory framework in place so that entity listings can stand up to legal challenges, especially in the wake of a Supreme Court ruling that has curtailed the influence of federal agencies in interpreting laws they administer. When deploying the US persons rule, which can have significant long-arm effects, the need for tailoring measures to mitigate broader spillovers is critical.

The Trump vs. Harris approach to list harmonization

List harmonization is one of the many questions hanging over the US election outlook for businesses on the lookout for emerging disruptions. Though both a Harris and Trump administration would employ list-based controls as part of their China strategy, the tactics of how each would deploy these tools would differ markedly, with big consequences for companies caught in the crossfire.

Maximalist vs. incremental: A Trump 2.0 administration would likely favor a blunter approach to streamlining sanctions and is unlikely to put significant resources into impact assessments before rolling out new measures. This could lead to abrupt and dramatic consequences for companies already struggling to screen multiple tiers in their supply chains for emerging sanctions risks.

In contrast, a Harris administration is likely to continue the Biden administration’s approach of incremental measures with phased-in timelines for implementation to mitigate supply chain disruptions. A Harris administration would also be more mindful of potential blowback from foreign partners if, for example, the US were to expand the number of Chinese entities subject to full blocking sanctions. This level of restriction can amount to a de-facto extraterritorial measure forcing foreign firms to choose between losing access to the US financial system or continuing business with a Chinese firm. Some Republican lawmakers, like House Representative Andy Barr, advocate for full blocking sanctions to ensure that American as well as foreign competitors are barred from transacting with the restricted entity to ensure a level playing field for US companies. But this argument downplays the economic and political consequences of the US unilaterally freezing out a firm that may be pervasive in global infrastructure and imposes equal costs on US and foreign investors.

Minding the “rip and replace” conundrum: A Harris administration would likely be wary of the rip-and-replace burden from restrictions that effectively ban critical tech inputs and involve a steep cost of replacement. FCC Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel reminded Congress in May that it is still $3 billion short in the funds needed to remove Huawei and ZTE equipment from their telecommunications networks. Even in cases where restrictions would not require a replacement of existing gear, but rather ban new purchases, regulators would still need to consider the cost of alternative suppliers. This issue is at the heart of the debate over when and how to place Chinese drone maker DJI on the FCC Covered List when farmers, emergency first responders, and other operators that depend on drone use would face much higher costs in replacing and growing their fleet with an alternative supplier.

Sidelining vs. elevating the Pentagon’s influence: Partiality toward certain agencies to administer sanctions lists will vary by administration. For example, in its final months, the Trump administration created the Communist Chinese Military Companies (CCMC) List in an executive order that introduced new investment-based restrictions. The list drew from the predecessor of the DOD’s 1260H List and placed DOD in the driver’s seat for new designations. The Biden administration later superseded that executive order with the creation of the Non-SDN Chinese Military Industrial Companies (NS-CMIC) List, which clarified that Treasury, rather than DOD, would drive designations for investment-based controls. The Biden executive order also expanded the scope of the NS-CMIC List to include companies involved in human surveillance technology.

While a Trump 2.0 administration would likely favor a greater role for DOD in managing sanctions designation, a Harris administration would likely lean on Treasury and Commerce. A May 2021 court decision overturned DOD’s decision to include handset maker Xiaomi on the Trump-era CCMC List, citing its “deeply flawed” designation process. This dealt a severe blow to the legitimacy of DOD as a sanctions program manager. In August 2024, it was reported that DOD reportedly removed LiDAR manufacturer Hesai from the 1260H List less than eight months after its inclusion. DOD may have concluded that it did not have strong enough evidence to withstand Hesai’s legal challenge. Nonetheless, the Hesai flip-flop could end up triggering a legislative amendment to expand the scope of the DOD’s 1260H List. As other Chinese entities pile on top of the Hesai legal challenge to 1260H Listings (Chinese semiconductor equipment maker Advanced Micro-Fabrication Equipment has filed a similar lawsuit), we expect a strong congressional counter-response. Republican lawmakers still see the DOD as the most pliable agency for designating Chinese entities and will be motivated to patch up legislation to avoid such mishaps in the future.

The scale and impact of list streamlining

Based on recent actions and proposals to cross-reference existing government red-flag and blacklists (see Table 2 in Appendix), this section envisages three scenarios for list harmonization and quantifies, where possible, the scale and financial implications of such scenarios.

Scenario I: Consolidating procurement restrictions lists

Procurement restrictions can act as a gateway to broader measures since federal authorities have more latitude to impose strict restrictions on suppliers that directly feed into government-funded and owned infrastructure. Once an entity is restricted for procurement, the door can open to further restrictions in the commercial sphere. Several US government lists are specifically designed to enforce procurement restrictions on companies and technologies deemed to pose a threat to US national security. However, the modalities of such restrictions differ, with some tailored to contracting agencies, while others target specific technologies. Some lawmakers argue that this creates “loopholes” in the security of federal supply chains and that a more consolidated approach is needed to both halt procurement from listed entities and prevent contracting with any entity that uses the products or services of the listed entity.

Parallel to this, there has also been a growing legislative effort to leverage federal contracting opportunities to pressure firms in sectors such as consulting or lobbying to sever their commercial relationships with listed Chinese entities altogether, not just as it relates to their use of technology products and services (see Table 2 in Appendix).

If the entities named across the main lists imposing procurement restrictions (i.e. the DOD 1260H List, FCC Covered List, Sections 889 and 5949 as well as the provisional BIOSECURE Biotech Companies of Concern List) were consolidated, it would cover a total of 86 parent entities. This would include major semiconductor firms like SMIC, CXMT, and YTMC, as well as leading biotech companies such as BGI and MGI Tech. Since restrictions often extend to subsidiaries and affiliates, the actual number of affected entities would be much higher. These 86 companies have at least 29 publicly traded subsidiaries which would also fall within the scope of these restrictions, not to mention their non-traded subsidiaries and other affiliates.

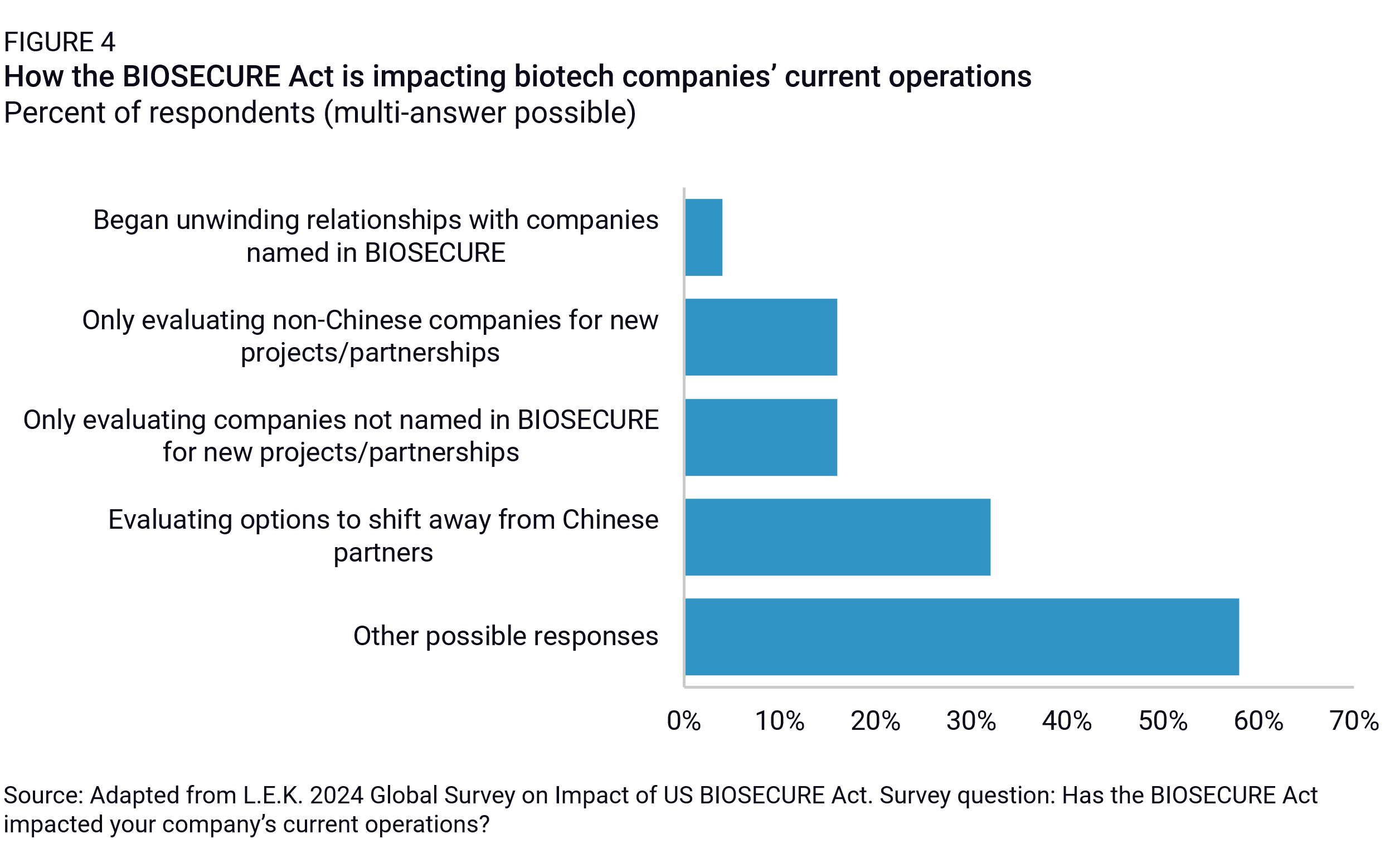

Besides the direct impact on Chinese company revenues, consolidated procurement restrictions would also have significant second-order effects on other government contractors reliant on input and services from these companies. For example, looking at the five companies named on the provisional Biotech Companies of Concern List from the draft BIOSECURE Act, these firms collectively generated at least $4.8 billion in the Americas in revenue, with Wuxi AppTech and Wuxi Biologics especially reliant on the US market (Figure 3). While not all of their US revenue is directly tied to federal contracts, broad procurement restrictions would likely decrease upstream demand for these companies’ products and services. A survey of US biopharma companies showed that 79% of respondents have at least one contract or product with a China-based or China-owned contract research or manufacturing partner like Wuxi AppTec. Another survey of US biopharmas indicates that 32% of respondents are already evaluating options to move away from Chinese partners, while 4% have already begun unwinding relationships with companies named in the draft legislation.

Scenario II: Expanding the NS-CMIC List

As Treasury inches closer to finalizing the rules for restricting outbound investment into China for a narrow set of technologies, Congress has been split between those supporting Treasury’s sectoral approach and those favoring an entity-based sanctions approach to restricting capital flows more broadly, including passive investments into Chinese equities via index providers and asset managers. Several lawmakers have lamented the Biden administration’s inaction on expanding the NS-CMIC List, leaving US investors free to invest in securities that have elsewhere been flagged as “bad actors” on other lists.

Against this backdrop, several lawmakers are now pushing for legislation to prohibit investment in entities named on any of the key US sanctions and red-flag lists, including any subsidiary, affiliate, and successor entities. Using the Treasury NS-CMIC List as a base and adding entities from other sanctions and red-flag lists (here we included the Trump-era CCMC List, the 1260H List, BIS Entity List, BIS MEU List, UFLPA List, FCC Covered List and Section 889 and Section 5949 Lists), the number of entities on the list would surge from the current 68 to 927. Furthermore, if the investment restrictions were extended to cover subsidiaries, as well as parent or holding companies, at least 68 additional entities would be impacted. The 68 entities currently on the NS-CMIC List represent $681.5 billion in combined market cap today, which would jump to increase to $969.7 billion if the list were expanded to include the 927 entities mentioned above.

To quantify the potential scale of such an expansion of the NS-CMIC list, we examine the China holdings of seven US-domiciled asset managers and funds. We find that the China portfolio of actively managed funds will likely not be heavily impacted by these potential expansions. However, passive index funds that were built to create broad exposure to Chinese equities could see up to 8% of their holdings being impacted by these changes. Sector ETFs that create exposure to specific sectors, including technology stocks, could also see significant pressure to change their investment strategy if an expanded NS-CMIC list comes into effect (see also De-Risking US Securities Investment in China).

Scenario III: Maximalist measures

More hawkish policymakers are calling for a more maximalist approach, arguing that investment restrictions like those tied to the NS-CMIC List are not sufficient to cut off all financing options. Proposals such as Rep. Andy Barr’s (R-KY) Chinese Military and Surveillance Company Sanctions Act would require Treasury to determine which entities from the Treasury NS-CMIC List, DOD 1260H List, BIS Entity List, and BIS MEU List should be moved to the Treasury SDN List, the “nuclear option” amongst all US government sanctions and red-flag lists. Such a move would subject a potentially large number of Chinese entities, including major tech companies with global exposure, to full blocking sanctions. Particular attention would be given to entities engaged in specific tech sectors such as semiconductor development, AI, quantum, and biotech.

In such a scenario, companies like Huawei, SMIC, Hikvision, or Zhejiang Dahua, which have the highest number designations across governments lists, would be at highest risk of facing an SDN designation. Looking at just these four companies, at least $40.2 billion in ex-China revenue and up to $67.5 billion in market cap could be at risk under full blocking sanctions, not to mention the costs borne by firms around the world that depend on their equipment and services.

Deploying SDN sanctions is a bazooka option with significant spillover effects. Such a move would effectively freeze out the company from global markets, creating significant rip-and-replace costs and disruptions. Other countries would resent such an extreme unilateral move, especially if applied against a broad set of entities. Critically, China could perceive such a move as a severe act of economic aggression and resort to more extreme tactics in retaliation.

We see the maximalist SDN List expansion scenario as the least probable. SDN sanctions are designed to be used narrowly and sparingly for maximum effect.

Looking ahead

A more likely pathway to the US ratcheting up sanctions would entail the following:

A proliferation of BIS entity listings under new footnote designations for military support, intelligence, or security end-use: For select targets, export control measures may be ratcheted up to Foreign Direct Product-level restrictions to deny US-origin IP more broadly. US persons restrictions are also likely to be employed more frequently.

Scope expansion for the Treasury NS-CMIC List: To resolve the gap between the technology focus of Treasury’s outbound investment screening regime and the large number of listed entities that are not subject to financial restrictions, an expansion of the Treasury NS-CMIC List appears inevitable. This would likely entail expanding the scope of the NS-CMIC List to cover additional theories of harm beyond “military-industrial complex” companies (harmonized with the revamped BIS entity listings for end-use) and including forced labor (harmonized with the UFLPA Entity List).

Inter-agency coordination on priority lists? The US election will likely determine whether sanctions listing across government agencies will become more streamlined. We expect a potential Harris administration would continue the work of consolidating lists, prioritizing key lists, and establishing an inter-agency process for determining list additions. Shifts in administration always run the risk of government expansion as new initiatives and areas of focus are announced, however. A Trump 2.0 administration’s preference for the DOD to assume the lead in list-making would also hinder this process.

Beyond the list: The Biden administration has already set an important precedent for preemptive technology-specific and geography-wide controls. Additional tools, such as expansive Commerce ICTS rules for cybersecurity and emerging DOJ data security rules will be employed to shut out Chinese entities from certain markets altogether. This trend will continue parallel to an expansion of entity listings.

Appendix