Beijing’s Russia Reckoning

Russia's military aggression in Ukraine and the concerted Western response to it will force Beijing into some hard choices

Russia’s military aggression in Ukraine and the concerted Western response to it are forcing hard choices in Beijing. Regardless of how China balances its support for Russia and its long-term interest in ensuring access to the global financial system, Beijing’s decisions in the coming months will be carefully scrutinized. So long as the G7 consensus on sanctions against Russia holds and the United States can credibly threaten secondary sanctions on Chinese institutions, China is likely to prioritize those institutions’ continued access to US dollar and euro financing. This means it is likely to encourage its big banks to comply with the financial sanctions aimed at Russia and tread carefully in helping Moscow navigate export controls on key technologies. Beijing will want to avoid becoming a bigger target for Washington. While there is some space for China to continue non-dollar trade with Russia through banks that are less exposed to sanctions, there are limits to how much Beijing can ease Moscow’s economic stress through trade.

Over the past week, we have witnessed a remarkably robust Western response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, including growing European support for cutting Russian institutions off from the SWIFT network, the freezing and seizing of the assets of Russian elites, and most significantly, the decision to extend financial sanctions and asset freezes to the Central Bank of Russia (CBR).

In the coming weeks, China must decide to what degree it will try to work around G7 sanctions in defiance of Western objectives as it tries to stay engaged with the Russian economy. On Wednesday, we received the clearest answer to this question so far from Beijing: Guo Shuqing, chairman of China’s banking regulator, stated that China opposed “unilateral” sanctions and would continue normal trade and economic relations with affected parties. China traditionally defines unilateral sanctions as those imposed outside of the United Nations, but given the robust sanctions that have been erected via G7 coordination, Beijing may be singling out US secondary sanctions and leaving the door open to counter-sanction moves down the line.

Beijing would clearly prefer to pursue a third way somewhere between the binary choice of supporting Russia or refusing to do so. That middle path involves quietly maintaining existing channels of economic engagement with Russia, as Guo’s remarks suggest, while minimizing the exposure of China’s financial institutions to Western sanctions.

The problem for Beijing is that maintaining economic and financial engagement with Russia will be hard to conceal under the current sanctions architecture. Moreover, the White House appears to be putting Beijing on notice that it intends to enforce secondary sanctions with the strategic intent of undermining the Eurasian entente. If the Biden administration follows this path, Beijing may have to consider a more aggressive strategy for countering secondary sanctions on Chinese institutions that continue to do business with specially designated nationals (SDNs) and blocked persons in Russia.

Chinese banks are already acting cautiously due to the risk of sanctions, with Bloomberg reporting that the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China’s offshore units and the Bank of China are restricting USD-denominated letters of credit for transactions between Russian and Chinese firms. Coal trading firms are apparently doing the same, awaiting policy guidance on these transactions. Beijing will need to tell them soon what they are allowed to do and what they should avoid.

Beijing faces a number of difficult choices in responding to the recent barrage of sanctions which we detail below.

Central Bank Sanctions

By far the most significant step thus far was freezing the assets of the Russian central bank, effectively leaving China as Russia’s main potential source of foreign exchange to defend the ruble and Russia’s financial system amidst significant capital outflows. Beijing will presumably allow the CBR to continue trading and accessing the portion of its foreign exchange reserves deployed in Chinese markets. That totals around $90 billion, according to the CBR’s January 2021 annual report, or 14.2% of Russia’s total reserves. The data shows that $81 billion of that Russian money in China — or almost all of it — is in RMB-denominated holdings.

It would be one thing for the CBR to access those reserves and trade in Chinese financial markets, but quite another for Beijing to allow the CBR to sell RMB-denominated assets for US dollars or euros. This could expose the Chinese entity involved in providing that foreign currency to sanctions. We expect that this would be a bridge too far for Beijing. The alternative—expanding an existing 150 billion yuan ($23.7 billion) RMB swap line with the CBR for trade settlement in energy or other areas—would also be seen as an aggressive deepening of China’s financial relationship with Russia, and would be difficult for Beijing to conceal.

Blocking Sanctions and Energy Carveouts

The United States, European Union member states, the United Kingdom, and Canada have also announced that they are cutting off some Russian banks from the SWIFT international payments system, including VTB and VEB. For now, it appears that their list excludes Gazprombank, key for energy transactions, and Sberbank, which has already been blocked from accessing dollar payments through the US financial system. The sanctions include carveouts for energy trade as the Western coalition (notably Europe) tries to mitigate the blowback on their own economies. There is plenty of room for the list of financial targets to expand in response to an escalation of Russia’s military aggression in Ukraine.

Even with these sanctions in place, Chinese firms can still conduct transactions, particularly those denominated in rubles or RMB, with Russian firms through other banks. However, despite a years-long push to increase the proportion of China-Russia trade denominated in home currencies, trade is still overwhelmingly invoiced in US dollars and euros (88% of Russian exports)[1]. Russia has replaced most of its dollar-denominated invoicing, but with euro invoicing, rather than RMB.

This composition can shift, of course, but it would require China to take steps to increase both RMB trade settlement of Russian exports (no problem for Beijing) and Russian imports denominated in RMB (which is more complicated). This would hypothetically create a “closed loop” of RMB and ruble-financed trade. However, that approach is unlikely to be sustainable beyond the short term, as traders would bear heavy risks from variation in prices, potentially ballooning trade imbalances if Russia’s position evolves to depend even more on China for all its imports, and the inability to properly hedge against shocks. As imbalances emerge, continuing this closed loop would require Chinese banks to bear the credit, currency, or sanctions risk from trading with Russian counterparties: it is improbable they are willing to do that, making a substantial increase in RMB-denominated Russia-China trade unlikely.

China can be expected to employ banks with less international exposure to maintain some level of trade with Russia. China’s transactions with Iran, for example, took place via the Bank of Kunlun, which was sanctioned in 2012. This was acceptable for China because the smaller lender did not have extensive linkages in the international financial system or large volumes of USD-denominated assets. If China wants to continue trade with Russian counterparties, it could use a similar approach, using smaller city commercial banks that could bear the brunt of US sanctions without risking extensive collateral damage to the rest of China’s financial system. It would then be up to the US Treasury to determine how many resources to devote to pursuing these banks’ counterparties.

Export Controls and Restrictions

Chinese executives will also have to contend with the threat of secondary sanctions on companies that supply Russia with technology using US-origin inputs, which sell sensitive dual-use goods, as well as the financial institutions which facilitate such transactions. For most established China-based technology firms, many of whom are already squarely in Washington’s crosshairs, the Russian market is not substantial enough to risk losing access to US technology over, and we expect these firms to tread cautiously.

For example, China’s largest export category to Russia is phones, accounting for 8% of overall bilateral trade worth $5 billion in 2021. This amounts to just 2.1% of China’s global phone exports, which total $220 billion. This trend also holds at the company level. Xiaomi in 2021 led the Russian market in total sales, generating some $1 billion in revenue from phone sales in the country. This accounted for just 3% of its estimated $30 billion in phone sales in the same year. For computers, the second largest Chinese export to Russia, Russian imports in 2021 amounted to $3 billion, a paltry 1.65% of China’s $181 billion in global computer exports.

Similarly, direct sales of integrated circuits (ICs) to Russia are minimal, comprising only $300 million of China’s total $108 billion in 2021 IC exports. Chinese semiconductors are exported to Russia as components in a variety of goods, including cars (2.5% of total exports), electric generators (2%), and televisions (1%). Notably, the current Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR) application against Russia focuses on military-industrial applications and has explicit carveouts for consumer electronics. While many consumer products may avoid inclusion in sanction-prone dual-use applications, major technology players in China that are still heavily reliant on US inputs may exercise more caution, while smaller consumer electronics firms could see a market opportunity in Russia’s growing economic isolation.

Beijing is painfully aware of how secondary sanctions against Iran ensnared a Huawei subsidiary in the Meng Wanzhou case as part of a broader pressure campaign against the Chinese telecom company over national security concerns. US application of the FDPR dealt a heavy blow to Huawei and exposed China’s vulnerabilities.

Even as China has poured resources into industrial and self-sufficiency policies to mitigate this risk, it remains dependent on US-origin technology inputs, particularly in the semiconductor space. Beijing does not want to see the United States apply FDPR to critical firms like Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), which already sits on the Department of Commerce Entity List. Still, Beijing could decide to invoke its Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law in defiance of US secondary sanctions, forcing its companies to choose between complying with US or Chinese law and creating the potential for bigger disruptions in high-technology value chains.

RMB Settlement

There has been some discussion that the international use of the RMB could expand in response to sanctions, but that possibility is remote. The basic constraints of China’s trade surplus and capital controls (as well as the present restrictions on outbound travel) prevent large volumes of RMB from leaving China and entering the international financial system. The internationalization of the RMB under these conditions depends on other countries’ willingness to accept RMB-denominated loans from Beijing and currency swaps for trade financing. (This includes the PBOC’s digital currency as well.) Russia could certainly increase those forms of borrowing, but Beijing would not be able to keep this secret: Russia would have incentives to publicly declare they had access to these new financing channels, for them to do any good. This would risk secondary sanctions for Beijing.

Similarly, the China Interbank Payment System (CIPS) is not likely to be a significant tool for sanctions avoidance, as it involves only RMB-denominated transactions and features just 75 direct participants, all of which are overseas branches of Chinese banks. The idea of the CIPS system when it was created back in 2015 was to serve as a replacement for the previous arrangement of designated individual RMB clearing banks within a particular country or jurisdiction. CIPS is not a replacement for SWIFT, an interbank messaging service, and SWIFT can be used within CIPS transactions. But for China to add Russian financial institutions to CIPS would be a notable and obvious step, even if the intent was just to expand RMB-denominated trade settlement while complying with existing sanctions.

Difficult Choices Ahead

Given the breadth and depth of G7 sanctions against Russia, Beijing will have little cover if it chooses to extend financial and economic lifelines to Russia in the near term. China’s leadership must consider several factors, including:

- How serious is the United States about pursuing secondary sanctions against major Chinese entities at a time when its primary focus is Russia? Will economic consequences of the sanctions, including cascading supply disruptions, alter Washington’s willingness to impose heavy punitive measures on China?

- Would Chinese sanctions-busting at a time of Russian military aggression accelerate joint action by the US, European and Asian partners to restrict technology exports to China and move supply chains out of the country?

- To what degree can China rely on other players such as India in circumventing sanctions? New Delhi is trying to balance trade ties with Russia against growing engagement with the West. It appears to be testing how far Biden will push for compliance at a time when the US wants Indian participation in regional blocs, like the Indo-Pacific Framework and the Quad, to counter China.

- Should the political imperative to push back against what China perceives as an overuse of US-led sanctions take precedence over practical economic considerations? Or should Beijing wait to see how the war and the international backlash against Russia play out, keeping tools like the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law in reserve?

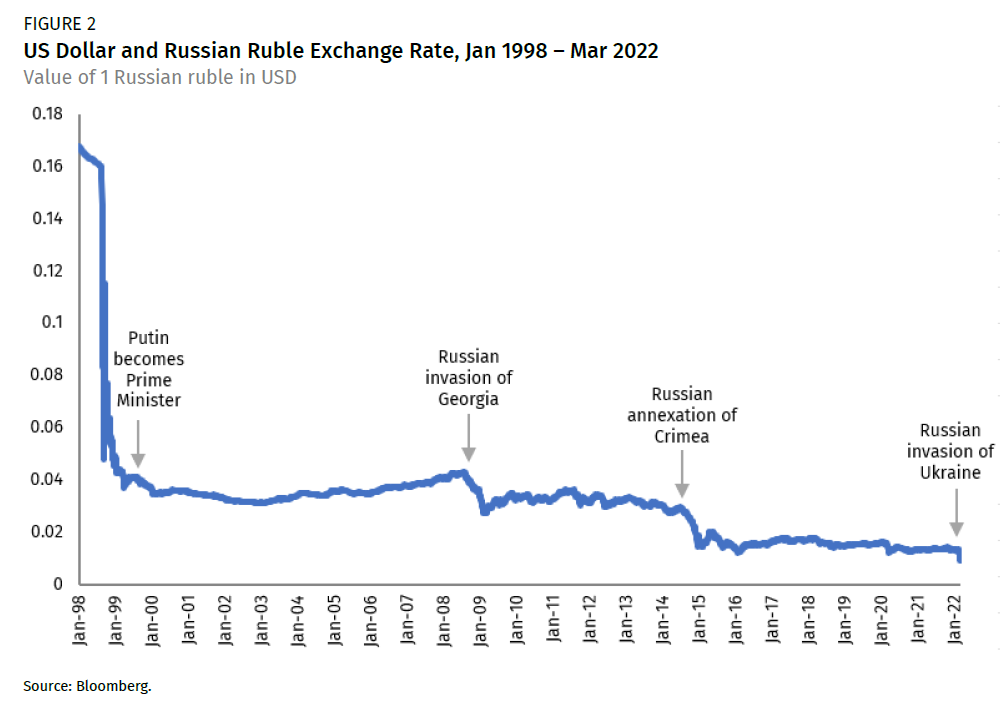

Both Moscow and Washington are pressing Beijing to make choices, which will either compound the pressure on the Russian economy or provide a safety valve. We suspect that Beijing’s guidance to banks and SOEs will err on the side of compliance in this heated stage of the conflict, while China’s spokespeople publicly declare opposition to “unilateral” sanctions. Beijing appears to have been taken by surprise by how far Russia has escalated its military campaign in Ukraine and is probably trying to assess, along with other governments, what a return to economic crisis conditions like those of 1998 will imply for political stability in the Kremlin.

There are still ways for China to maintain some level of RMB-denominated trade and push back on sanctions in less sensitive areas, but Beijing will not want to accept collateral damage to its economy because of a Russian military misadventure. When the hot phase of the conflict ends, China could try to position itself as a mediator. From this position, it could look to undermine G7 solidarity and reinforce its narrative of an emerging multipolar order — one in which China is the dominant Eurasian power, maintains important economic ties to the West, and is not constrained by political choices made in Moscow.

[1] Mrugank Brusari and Maia Nikoladze, “Russia and China: Partners in Dedollarization,” Atlantic Council, February 18, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/econographics/russia-and-china-partners-in-dedollarization/.