COVID-19 and China’s Household Debt Dilemma

Economic fallout from the COVID-19 outbreak now threatens to intensify the financial risks arising from the increase in Chinese household borrowing, with implications for financial stability, consumption growth, and the broader economy

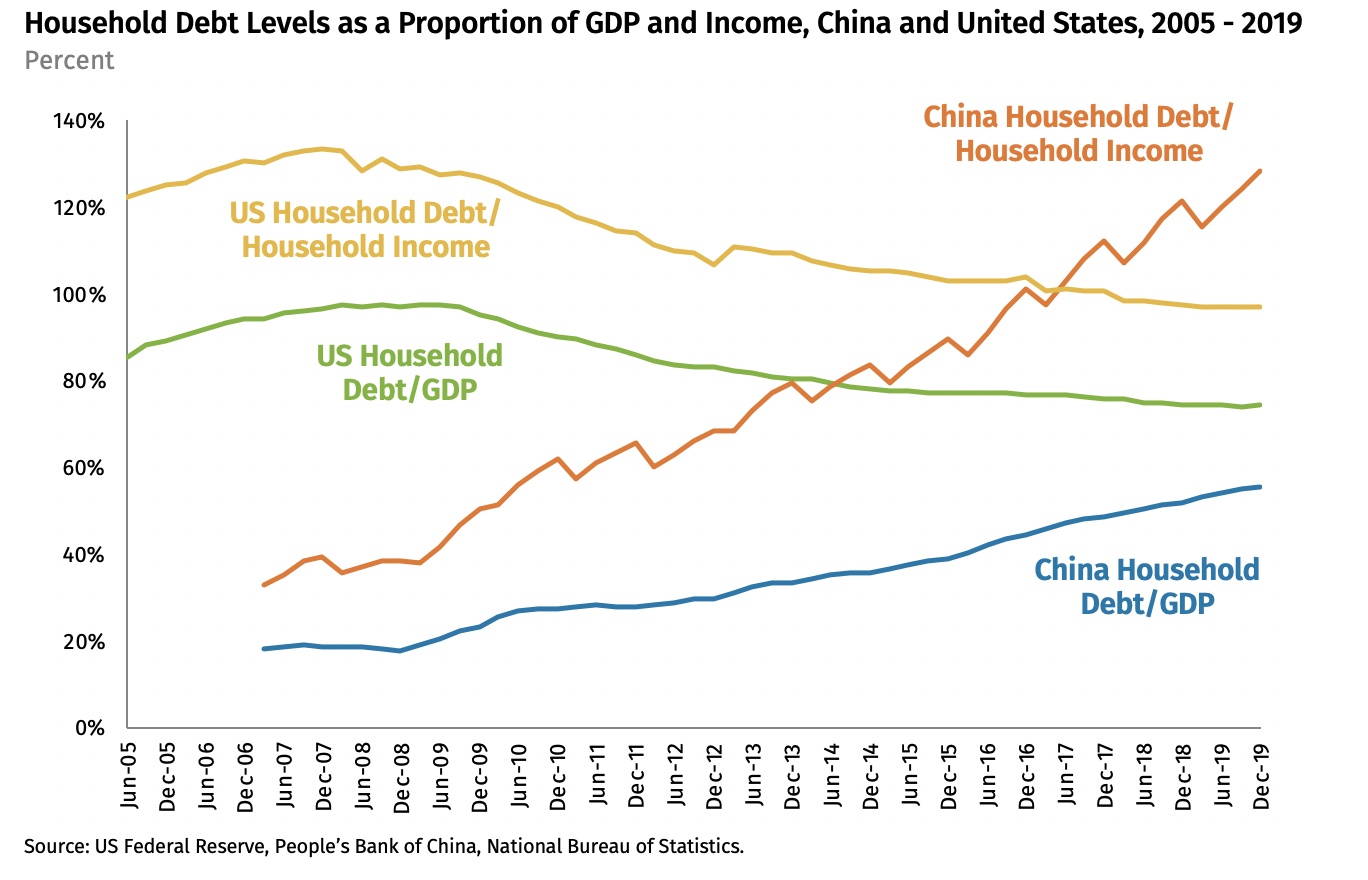

China’s households have been among the world’s best savers—until recently. In only five years, household debt has surged to 128% of household income, and 56% of Chinese GDP. While most of this growth is tied to China’s property market in the form of mortgage debt, consumer credit has expanded rapidly as well: credit card debt in China now exceeds US levels in absolute terms. Economic fallout from the COVID-19 outbreak now threatens to intensify the financial risks arising from the increase in household borrowing, with implications for financial stability, consumption growth, and the broader economy.

We recently examined China’s rising household debt burden in detail, including the financial vulnerabilities from virus-related shutdowns. Our key findings are:

- China’s recent household debt expansion rivals that of the United States pre-crisis, within a smaller economy. Over the past five years from 2015 to 2019, China’s households have added $4.6 trillion in borrowing, compared to a $5.1 trillion expansion in US household debt from Q3 2003 to Q3 2008.2008.

- Most household debt is linked to the property market, so household debt growth should slow this year.Property sales have been impacted by the virus, and mortgage loan growth should decelerate, along with overall household debt.

- The economic fallout of the virus outbreak may include rising household defaults. The industries hit hardest by virus-related shutdowns are among the lower-wage industries in China.

For years, China’s financial system grew rapidly, but most bank credit was allocated to state-owned enterprises. Loans were generally backed by fixed assets as collateral or government guarantees, and the proceeds were invested in new fixed capital rather than consumed. As a result, even though credit expansion was extremely fast, China’s credit growth was thought to be different in nature from the consumer debt bubbles that had produced financial institution defaults and insolvencies in developed markets when they finally burst. Corporate leverage to fund new investment was generally viewed as more stable than household leverage to fund consumption.

What a difference five years makes. From the end of 2014 to 2019, China’s corporates added an astonishing 37.9 trillion yuan in new formal borrowing ($5.5 trillion). But China’s households joined in the party for the first time, adding 32.2 trillion yuan in debt from banks alone ($4.6 trillion). The surge in China’s household borrowing is comparable in size to the runup in US household debt in advance of the global financial crisis (although household debt was not the only factor involved in that crisis, of course). US household debt rose by $5.1 trillion from Q3 2003 to Q3 2008.

Simply put, the structure of China’s debt has changed significantly in the last five years, and risks from both corporate and household borrowing are now prominent. There are already limits to how much new debt corporates can add, given the rise in defaults, the declining marginal returns to new credit and investment, and the rising proportion of credit used to service older debt. The historically underleveraged household balance sheets were the last frontier of China’s historic credit expansion.

Some expansion in household borrowing was therefore predictable, as households have historically been underbanked in China, when the system favored state-owned corporates. The question now is whether or not the rise in household debt has been too fast, given the pressure that the virus outbreak and its corresponding economic shutdowns will place on employment and household incomes. The imbalanced structure of the Chinese economy is a key source of financial system risk: household incomes make up a far smaller proportion of China’s economy than in a more developed one. They are estimated at only 43% of GDP in 2019, a proportion that has remained relatively stable throughout the past decade. As a result, even though the aggregate level of household debt in China (conservatively estimated via bank loans at 56.5 trillion yuan or $8.0 trillion at the end of March) is only a bit over half of US levels, the debt level is now similar in size to the pre-crisis United States level as a proportion of household income

There is no magical threshold of danger in household debt to income ratios: those in other developed economies are higher and likely sustainable. But as the second-largest economy in the world, the absolute levels of debt incurred in China are already quite large. Throughout the past decade, China’s households have outpaced their American counterparts in adding new incremental borrowing in absolute US dollar terms every year since 2009.

How did we get here?

How and why did China’s household debt rise so quickly? We would argue that four factors were involved, which are critical to understand how household debt growth might change in the future.

First, because of slowing economic growth in 2014 and 2015, China’s leaders directly and indirectly encouraged household borrowing. The sharp slowdown in China’s property sector and the deflationary forces gripping China’s industrial sector in 2014 and 2015 left the government with few options. More credit flowing to zombie enterprises was producing surpluses of raw materials and manufacturing goods, and deepening deflationary pressure, while demand was weak. The 2015 stock market boom and bust, and the corresponding capital outflow following the exchange rate adjustment in August 2015 forced policy-makers to look around for new drivers of growth. Consumer credit was seen as facilitating the rebalancing of the economy at the time by accelerating consumption, and Chinese authorities encouraged consumer borrowing.

Second, the still-buoyant property market facilitated and then required a rapid expansion in household borrowing. Most of China’s expansion in household debt in recent years has been mortgage debt, which the PBOC places at 30.1 trillion yuan ($4.3 trillion) as of the end of 2019, up from 11.5 trillion yuan at the end of 2014. As official mortgage debt has almost tripled in five years, property prices have also risen, and households have needed to borrow more to participate in the market. Without strong investment-driven demand for property, it is unlikely that China’s household debt would have grown so quickly. But the rise in property prices also requires additional borrowing by households to sustain the market. Even the average purchase of a house at the average price nationally currently requires annual mortgage service costs higher than urban per capita annual income at present (See Apr 2, “Property Developers’ Dollar Bonds: Dancing in a Minefield”).

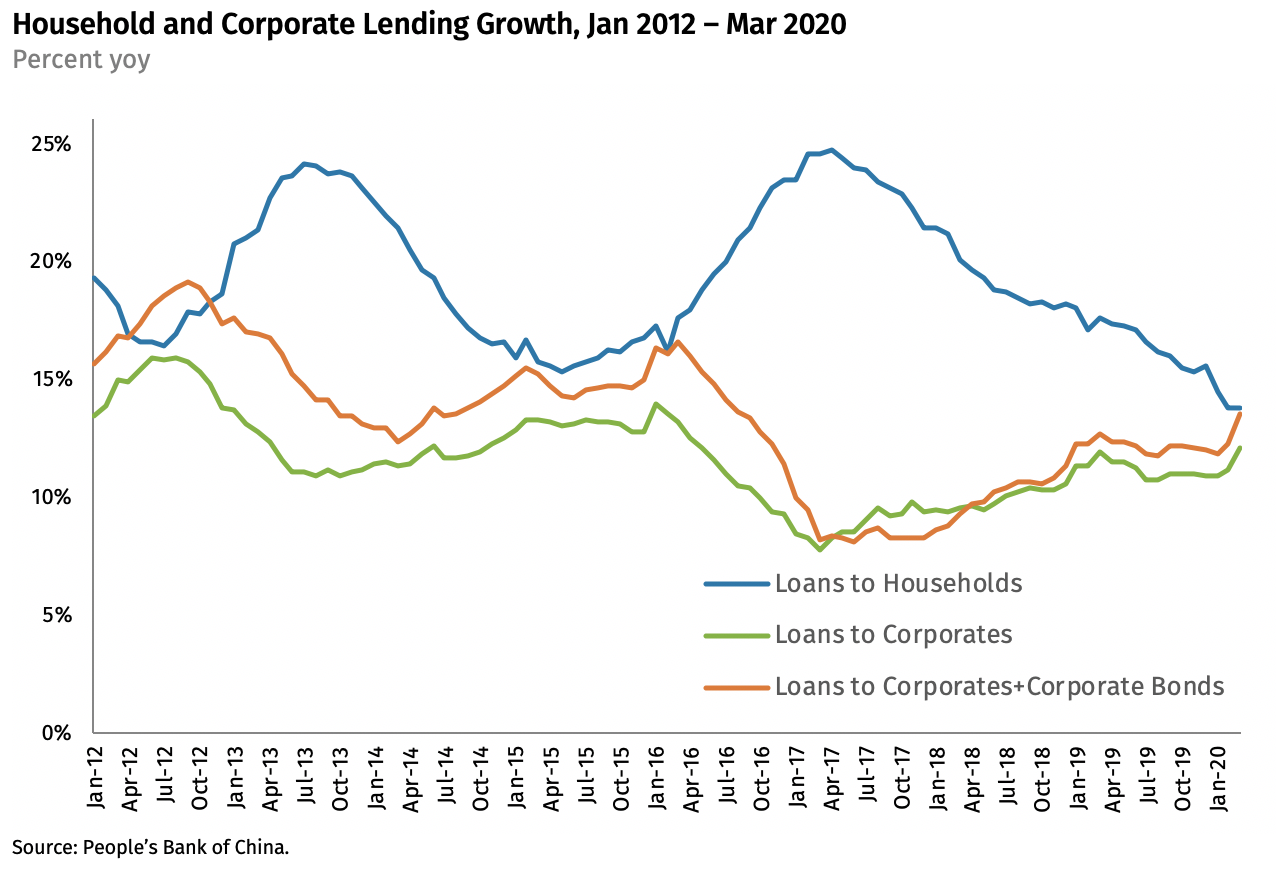

Third, the deleveraging campaign launched in late 2016 redirected banks’ incentives to lend to households rather than corporates. The deleveraging campaign first saw banks’ funding costs in China’s money markets rise, and then saw regulatory crackdowns on shadow financing instruments that had previously delivered higher returns. Regulators pressured banks to migrate assets back to formal balance sheets, which reduced banks’ net interest margins. The net result of this was to encourage banks to add lending to households, since mortgage interest rates were higher than corporate lending rates, particularly on loans to state-owned enterprises and local government financing vehicles. As a result, lending to households actually outpaced lending to corporates during the most intense six quarters of the deleveraging campaign (Q3 2017 to Q4 2018).

Fourth, online payment platforms and new financial technologies created new mechanisms for households to engage with the financial system and borrow, from both banks and non-bank intermediaries. Some of the debt incurred by households via peer-to-peer lenders or online payment platforms is not included in the totals above, which reflect official totals from the banking system. But the availability of financial services on mobile platforms also helped consumers to service their debt burdens by borrowing for bridge payments. The growth of financial technologies has helped to normalize consumer credit for Chinese citizens and has helped to facilitate other forms of borrowing, such as credit card debt.

The Virus and the Outlook for Household Debt

The COVID-19 outbreak and corresponding economic shutdowns now pose new risks to the stability of China’s household debt, and thus the broader economic recovery. While state-owned enterprises were capable of returning to work quickly in March after the February shutdowns, many migrant workers and employees in the private sector and the services sector have been much slower to return, costing them incomes (See Apr 6, “China Industrial Recovery Chartbook”). Employment prospects are weakening at present in the construction sector and export-oriented manufacturing as the property sector and global demand sputter, while services sector activity has yet to return to normal levels. Activity levels are increasing gradually, but remain below typical patterns in production and capacity utilization.

Low-wage industries are among those most likely to be affected by virus-related closures. This increases the risk of defaults on consumer credit, because lower-income borrowers are more likely to be impacted by the recent shutdowns. Even if the overall household debt burden appears sustainable in a macro sense, the distributional impact of household debt on lower-income borrowers may drive additional risks as the economy slows. Particularly at risk from this potential hit to household incomes is short-term credit card debt. China’s credit card debt now totals 7.59 trillion yuan at the end of 2019, or $1.09 trillion, compared to $927 billion in the United States at the end of last year. Credit card borrowing in China has risen by 87% since the end of 2016, and credit lines available now total 17.4 trillion yuan ($2.5 trillion). Even though household lending growth has slowed, it continues to outpace corporate lending growth.

While China’s household debt burden is currently slowing discretionary spending, household consumption continues rising gradually as a proportion of China’s economy. Should the virus-related shutdowns weaken household incomes and employment, the impact on consumption may dwarf any pickup in investment-led growth from more traditional stimulus measures. This is what makes the prospect of defaults on household debt so dangerous for the overall growth outlook, by magnifying the ongoing slowdown in household consumption.

Exposure by regions and banks

Our research also delved into which Chinese regions and banks are most exposed to the rise in household debt. It showed that most household debt is concentrated in eastern and southeastern coastal provinces, where property prices are higher. This includes the four so-called “tier one” property markets – Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen.

As for the banks, we expect those with heavy exposure to retail borrowing, especially credit card loans, to see more delinquencies. Forbearance measures by regulators may help banks postpone recognition and provisioning for non-performing loans, but these assets will remain on their balance sheets, amplifying capital pressure on China’s commercial banks. We expect that most of the impact of the virus outbreak on banks’ asset quality will not emerge until the Q2 or Q3 interim reports.

For more information on regional and banking exposure, please contact the authors.