China’s External Debt Renegotiations After Zambia

Beijing finally appears to be changing its approach in providing debt relief to emerging markets.

Beijing finally appears to be changing its approach in providing debt relief to emerging markets, given a recent deal on restructuring bilateral loans to Zambia. Our proprietary dataset concerning China’s external debt restructurings, now updated through March 2023, reveals over $78 billion in China’s external debt under renegotiation since 2020.

The shifts in Beijing’s positions are still only incremental. China participated in the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), but continues to negotiate separately from other creditors. The Zambia deal reveals that China’s Export-Import Bank may still not be speaking for all of China’s lenders in the course of negotiations. In addition, Beijing’s banks remain insistent on extending loan terms and adjusting financing costs rather than accepting haircuts on principal. But Beijing’s tactics may change further as financial stress in emerging markets builds.

Our data also casts doubt on recent claims that China has engaged in widespread rescue lending over the past decade. Instead, new funding appears to be concentrated among China’s most indebted borrowers, such as Pakistan, and limited in other cases.

The Zambia Effect

The June 22 announcement that Zambia had reached a tentative restructuring deal with its bilateral creditors—including China—opens up a new stage in global negotiations over debt relief to emerging markets in financial distress. Since defaulting in 2020, talks had languished, while outside analysts blamed China’s banks and their apparent unwillingness to accept either IMF debt calculations or haircuts on their substantial loans. The tentative deal has the potential to offer real relief to Zambia, pending the outcome of negotiations with private creditors, but also involves contingencies based on a review of Zambia’s progress. The deal also represents China’s creditors resorting to more traditional preferences, while preserving the principal on the original loans.

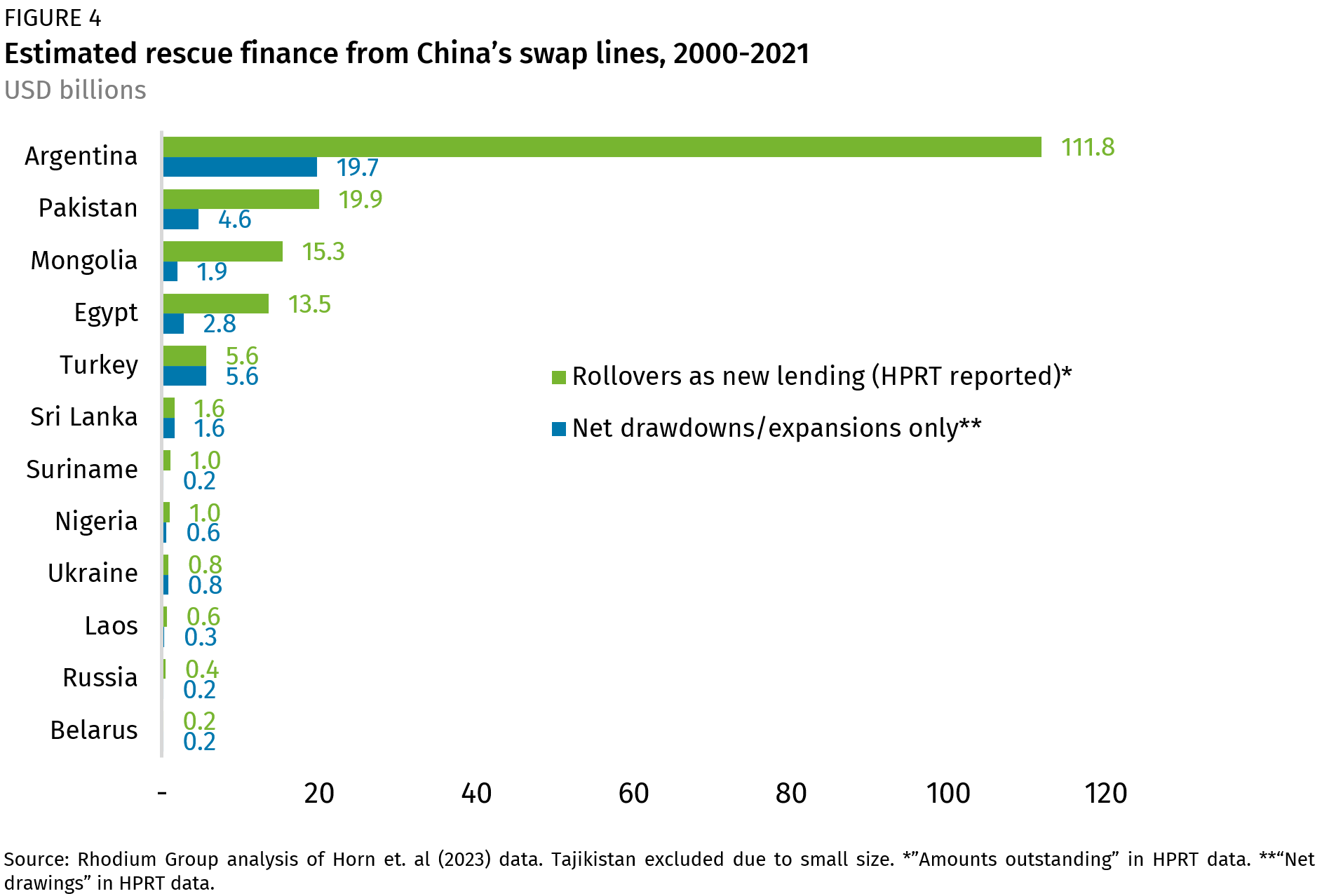

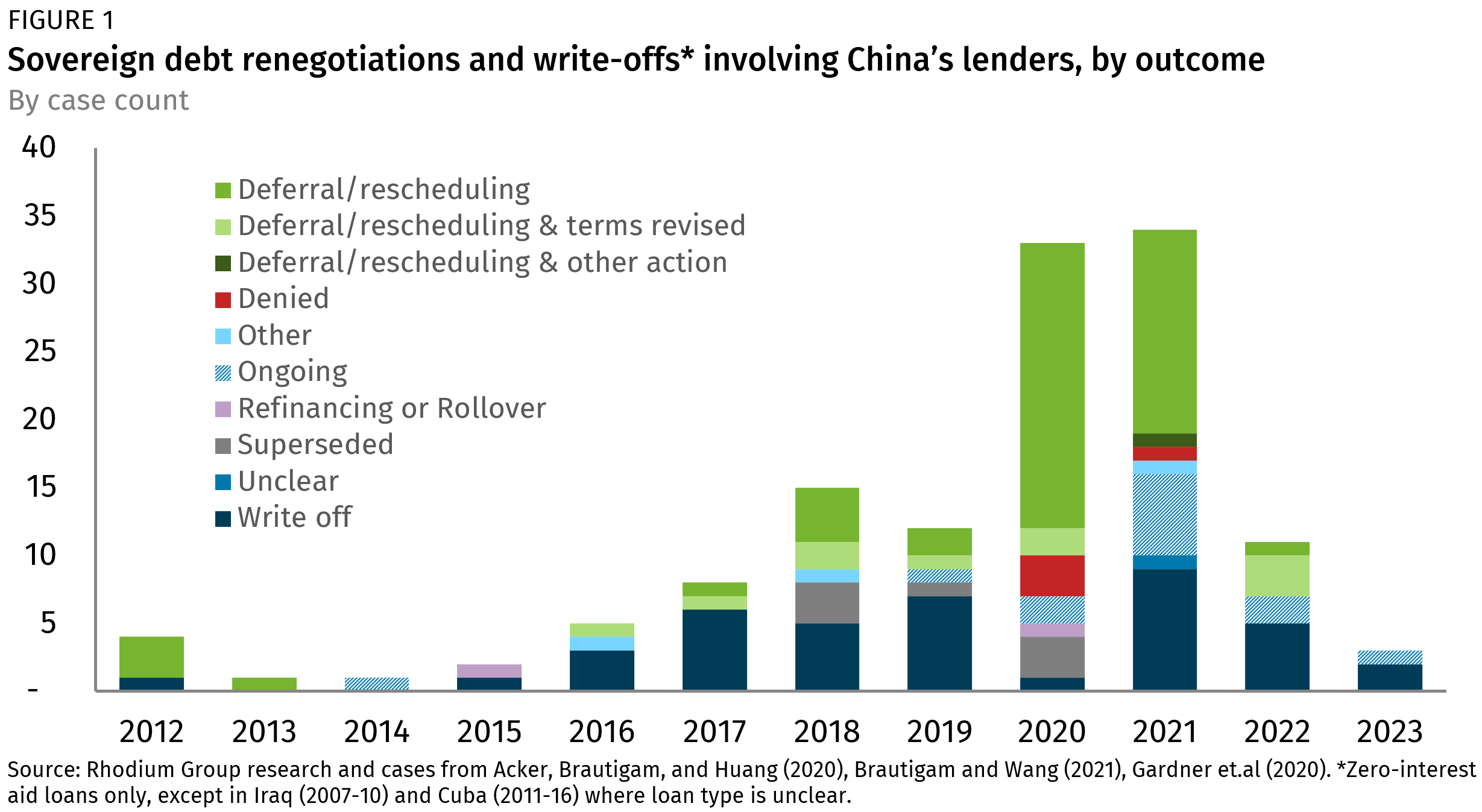

The key question is what will happen next, and whether or not the change in Beijing’s approach in the Zambia negotiations, which corresponded with an in-person appearance by Premier Li Qiang in Paris last week, will be reflected in other cases. To aid this discussion on the prospects for alignment between China and key external creditors in other countries, from Sri Lanka to Suriname, in the context of a new deal on Zambia, we have updated our proprietary dataset on China’s external debt renegotiations since 2020, with the results presented in Figures 1 and 2.

We estimate the total amount of sovereign debt under negotiation since 2020—a mix of principal and deferred income—is over $78 billion. New sovereign debt negotiations(- Includes government debt and government-guaranteed debt (primarily debt to SOEs), where identifiable. ) and zero-interest loan write-offs involving Chinese creditors(- These creditors include China’s policy banks (Export-Import Bank of China/CEXIM and China Development Bank/CDB); commercial banks like the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), and the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA), which administers zero-interest foreign aid loans.) totaled $9 billion in 2022 (11 cases) and $1.7 billion in 2023 through April (3 cases).*(Outcome classifications are included in Appendix A. ) This is a decline from 2021 ($19 billion), which featured a large volume of deferrals during the final year of the DSSI, as well as new negotiations under the Common Framework.(- Officially, the Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI.)

Recent cases show China’s lenders slowly shifting their approaches to multilateral debt renegotiations. China’s lenders have long preferred to negotiate separately from other international creditors and on a case-by-case basis.*(Although China provided some write-offs in parallel to the multilateral Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative in the early 2000s, it did not fully participate; it did not negotiate as part of the Paris Club or enforce policy conditionality, though it did require countries to recognize the PRC (and not Taiwan). See Deborah Brautigam, The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa (2009); and World Bank, Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) Statistical Update, July 26, 2019. ) Against this backdrop, China’s decision to participate in the DSSI beginning in 2020 was a substantial development, and reflected the recognition by Chinese lenders and policymakers that China cannot address sovereign debt issues unilaterally.

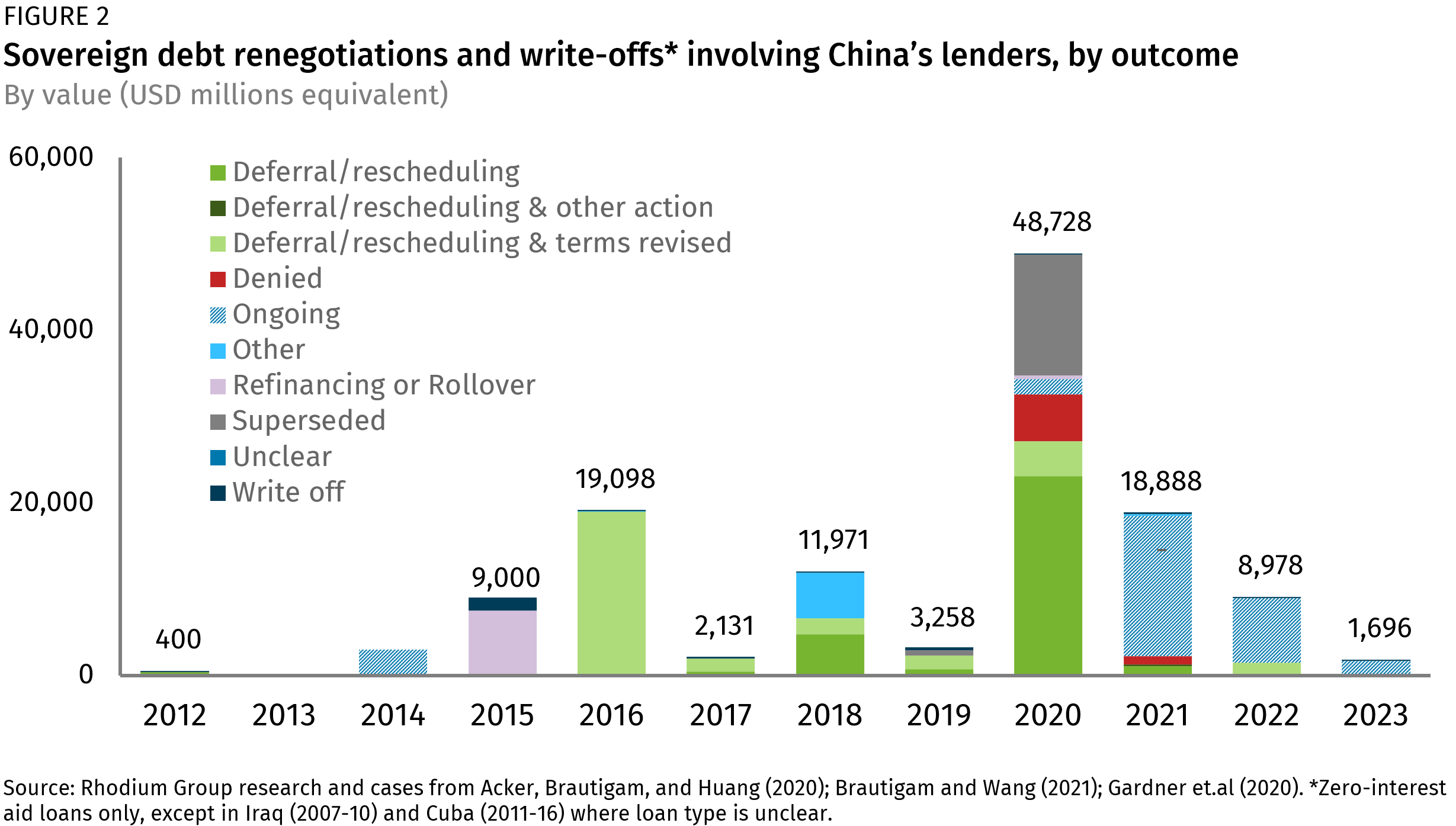

But the DSSI did not represent a complete paradigm shift. The initiative’s terms matched creditors’ existing preferences to reschedule payments on net present value (NPV)-neutral terms, paving the way for China’s participation, and Chinese officials continued to negotiate suspension agreements bank-by-bank, independently from the Paris Club creditors. But China’s participation was still meaningful, with Brautigam and Huang (2023) estimating that China deferred $8.2 billion in payments in 2020 and 2021.

However, borrowers did not equally share these benefits. Based primarily on national-level sources, we assemble an alternate measure of DSSI deferrals as part of our larger dataset of China’s debt renegotiations. Our data suggest DSSI relief was highly concentrated in a handful of countries with large loan exposures to China (Figure 3). Angola had more debt to Chinese creditors deferred than any other country, though estimates depend on how deferrals by the China Development Bank (CDB) and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) are treated. In the face of incomplete national source data for Angola, we adopt well-justified estimates from Brautigam and Huang (2023), which show around $5 billion—almost two thirds of total deferrals—went to Angola alone. Pakistan received approximately $1 billion in deferrals, followed by Kenya and the Republic of Congo.

While for most countries in our dataset, national-level data is consistent with World Bank data (totaling $4.2 billion), in some cases, our estimates are much lower, or available national sources do not provide deferral amounts. One example is Zambia, where the World Bank records $500 million in DSSI deferrals, compared to our estimated $110 million in deferrals. In other cases, like Myanmar, we can confirm deferral agreements were signed, but cannot isolate specific amounts. These discrepancies appear related to CDB debts. In Zambia and Myanmar, and a handful of other countries, CDB agreed to defer debt payments for short periods. Yet national authorities, the World Bank, and sometimes even Chinese sources disagreed on whether these CDB deferrals should be counted as DSSI activity or “voluntary” actions outside the scope of the DSSI, and these differences have yet to be rectified. Brautigam and Huang describe coding discrepancies in World Bank databases may be partly to blame, but our dataset suggests that the blurry lines between concessional and commercial lending persist. These distinctions between “official,” “bilateral,” and “commercial” lenders did not much matter for the highly circumscribed DSSI program, but are important for navigating more complex negotiations such as the deal in Zambia’s case.

Besides the DSSI, China’s most visible action on debt relief since COVID-19 has been zero-interest loan write-offs, but the pace of new write-offs also appears to be slowing. We tracked 16 write-offs between 2021 and April 2023, all in African countries. Chinese officials had previously pledged to cancel a total of 37 loans maturing in 2020 and 2021, without naming the specific countries involved.*(At the 2021 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) China claimed that it had written off interest-free loans for 15 African countries that matured in 2020. A year prior, China pledged it would cancel loans of “relevant African countries” without mentioning specific amounts or partners.) The total value of write-offs from 2021-2023 in our dataset was $231 million(- USD equivalent, as China’s zero-interest loans are denominated in RMB.). At an average of around $15 million, this suggests that the total value of China’s write-offs during the pandemic may be towards the low end of recent estimates by Boston University researchers, ranging from $45 million to $610 million. Fewer zero-interest loans will be available for China to write off in coming years, and they remain politically sensitive, limiting the rhetorical benefit to Beijing.

Marginal Shifts in Beijing’s Approach to Negotiations

China’s participation in the DSSI has not facilitated more complex negotiations involving multilateral actors and the IMF, at least so far. Outside analysis suggests that China’s participation tends to slow both the arrival of IMF funding as well as ultimate debt restructuring agreements, and current negotiations are no exception. That Zambia took more than two years to get to financing assurances, and then a further 11 months to announce initial debt restructuring terms, does not show China’s financial institutions moving with alacrity. The known details of the Zambia deal suggest that these dynamics will persist:

China’s creditors are still negotiating separately. Although China EXIM represented “official creditors” in the bilateral creditor committee, it is unclear (and ultimately unlikely) that CDB debt is included in the deal.*(This would be consistent with Zambian financial disclosures, which consistently refer to CDB as a private or commercial creditor, including during the DSSI period.) Subsequent statements by Zambian officials clarified that $1.75 billion in commercial debt covered by Sinosure export credit insurance—which might otherwise qualify as official finance—is excluded and must be handled in subsequent private-sector talks. Zambian debt statistics suggest that the loans covered by this $1.75 billion in credit insurance represent the remainder of Zambia’s central and government guaranteed debt, excluding a loan for the Kafue Gorge project.

The strategy for China EXIM—delay and extend—is not new. The Zambia deal is well in line with the broader patterns in our renegotiation dataset, which suggests deferrals and rescheduling remain China’s (and China EXIM’s) preferred options. Long extensions are not unprecedented, and extension of facilities by 15-20 years were used in China EXIM’s approach to the Republic of Congo (2019) and Ethiopia (2018), and extensions between 5-10 years featured in Ecuador (2021).

China EXIM may still come out ahead. Much of China EXIM’s known exposure to Zambia consists of government concessional loans and preferential buyers’ credits that carry a standard 2% interest rate, which are partially subsidized by China’s government. Although the agreement includes a three-year grace period, only under the so-called “base” scenario would these loans feature an interest rate reduction (to 1%) for most of the new payment period; even under that base scenario, rates will increase to 2.5% in later years. The upside or “contingency” case—based on an IMF assessment of debt capacity at the conclusion of the program in 2026—would see interest rates increase to 4% and the maturity shortened. This feature potentially allowed China EXIM negotiators to sell the deal internally and externally, and harkens back to the Republic of Congo case, when China EXIM required a third of all outstanding debt be repaid within three years.*(IMF reports suggest that the Republic of Congo continued making payments on these “Strategic Partnership” loans even during the COVID-19 pandemic, when it was eligible for the DSSI. See “Résumé de l’Accord de restructuration de la dette du Congo envers la Chine,” May 22, 2019; “Partenariat stratégique Congo/Chine,” June 21, 2021; and IMF Country Report No. 23/98, February 2023.)

High-level political diplomacy may still be required to reach an outcome. The Zambia deal was announced during premier Li Qiang’s visit to France to attend the Summit for a New Global Financing Pact, and follows numerous bilateral meetings between Zambia and China since 2020. There has been a consistent pattern in our dataset: large restructurings are often associated with high-level bilateral meetings, including with Xi Jinping. Borrowers likely recognize these dynamics, as Ecuador’s successful 2022 restructuring followed early visits to Beijing by the Ecuadorian president, and Ethiopia has held bilateral talks in China with high-level officials outside of the official Common Framework creditor committee.

Beyond coordination issues, other hurdles remain for the other ongoing negotiations. There have been complaints from Beijing that debt sustainability analyses (DSAs) were not sufficiently disclosed, but in the cases of Zambia and Sri Lanka, China’s creditors have taken larger issues with the DSA methodology. When a creditor makes financing assurances to the IMF that it will provide relief—a necessary precondition to IMF bailouts for the borrower country—the DSA ultimately determines how much relief that creditor must provide. While China may have legitimate objections to the DSA, outside analysts have pointed to the potential for China to drag out—or threaten to drag out—negotiations by continuing to object to DSA assumptions to reduce their losses. The Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable aims to address these issues by bringing together MDBs, all major official bilateral creditors, borrower countries, and a handful of international bank representatives, and has helped clarify information-sharing agreements, and the IMF and World Bank have moved to share DSAs more widely.

Beyond these constraints, however, negotiations and haircuts alone will not be enough to resolve emerging market debt problems. Mobilizing new financing, including from the private sector, is urgently necessary. There are good reasons to doubt the capacity of Beijing to provide additional funding, after defaults on China’s previous loans have surged, and domestic debt problems continue to plague China’s policy banks, particularly the China Development Bank, which affect the prospects for overseas lending.

China’s Limited Role as a Rescue Lender

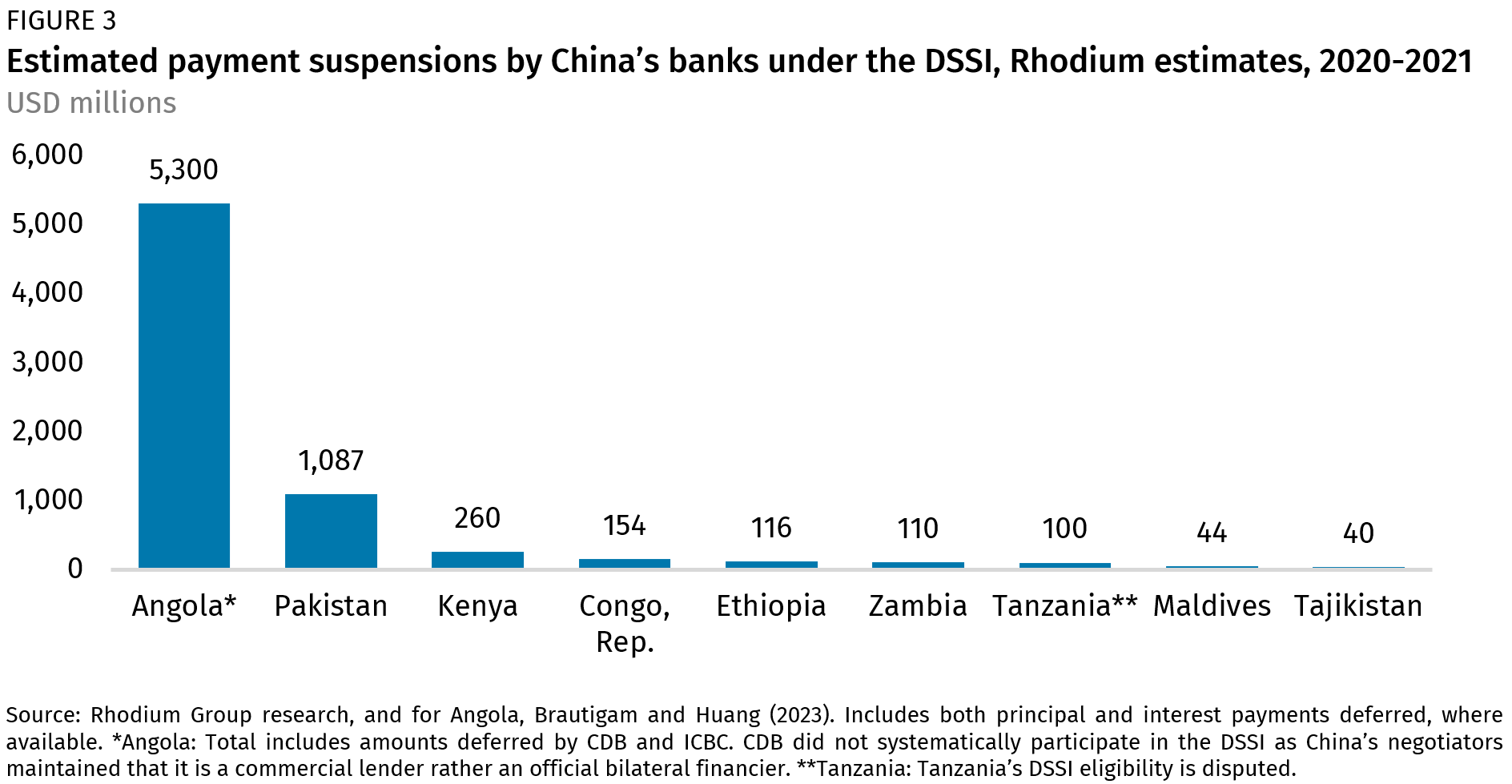

With questions over the World Bank’s capacity to surge lending, and IMF procedures under scrutiny, attention has turned to China’s role as a provider of liquidity and “bailout” finance. A recent paper by Horn, Parks, Reinhart, and Trebesch (“HPRT”) claims that China has extended $240 billion in rescue lending between 2000 and 2021, including PBOC foreign currency swap lines, large foreign currency facilities from CDB and commercial banks, and general budgetary support loans. These financing modes have been in the spotlight as Pakistan, Egypt, and other countries struggle under balance of payments pressures, and have been key to unlocking IMF support in several cases.

Some media reports, and HPRT, characterize these flows as refinancings or rollovers of China’s loans. This is at odds with our renegotiations dataset, where explicit refinancings and rollovers are less common. BOP support and other loans are an important part of China’s financial engagement with certain countries, but our data suggest that bailouts and rollovers are not the primary outcome (or desired strategy) for Chinese lenders to manage their overseas loans. This may be partially explained by our outcome definitions (Appendix A). But our review of HPRT data also suggests the authors may overstate the volume of bailout finance from China by several billion dollars.

The HPRT estimates are potentially skewed by authors’ treatment of foreign currency swap lines and swap line rollovers. As HPRT note, rollovers are commonplace, as are renewals of the underlying three-year swap agreement. However, the authors treat each swap line rollover as an expansion of financing, identical to a wholly new swap line or loan, with a value equivalent to any drawn amounts outstanding at the end of the year. The effect is to count the same swap line multiple times, inflating the total. This can be seen when data is broken out by country, and especially in HPRT’s estimates for Argentina (Figure 4).

As reported, the HPRT data claim Argentina received $110 billion in rescue lending via swap lines alone from 2012-2021—65% of the total estimated bailout lending in the HPRT dataset. With credible estimates of China’s overseas finance to emerging markets during the BRI period ranging from roughly $800 billion to around $1 trillion, this would imply Argentina received roughly 1 of every 8-10 dollars of Chinese lending during the same period—an implausibly high proportion. An alternative data approach would be to treat only net expansions of the amount available under the swap as new financing. Taking new net financing suggests that Argentina received less than $20 billion in rescue lending. Applying this to the rest of the dataset reduces the estimate of China’s rescue lending by over 50%, to approximately $100 billion over 20 years—a much more realistic total. This is not to say that that China has not provided any loans to shore up third countries’ balance of payments positions or expanded swaps since 2021, when the study period ends; in the interim, Pakistan has been a major beneficiary. However, these can be valued in in the low double-digit—not triple-digit—billions of US dollars, and most countries should not think of China as a lender of last resort.

The Next Chapter for Beijing’s Negotiations with Emerging Markets

The data on renegotiations since 2020, including the recent developments in Zambia, suggest that China is slowly adapting its approach within these discussions. On the other side, the IMF’s approach to China has been relatively lenient. For example, the Fund has accepted delays and sometimes ambiguous financing assurances from China to unlock bailouts, even as it held the line on the issue of multilateral haircuts. That approach appears to have finally paid off, defusing (for now) the question of lending-into-arrears. But our dataset and the Zambia agreement show China’s preferences and internal economic and political constraints remain unchanged.

Deferrals and rescheduling—rather than explicit rollovers or refinancing—remain the most likely outcomes for most countries engaging with China on debt. Future debt agreements will likely need similar upside-preserving features to make them tenable within the policy banks, as well as high-level political support from outside the creditor committees. As in the DSSI, the question of non-China-EXIM debt remains unresolved. And with the possible exception of Pakistan, most countries should not expect China to provide a surge of new rescue lending, whether via bilateral currency swaps or other means. All eyes now turn to Sri Lanka, where China has thus far participated only as an observer to the bilateral creditor committee. If the Zambia outcome does not pave the way for a prompt resolution, and negotiations appear intractably stalled, the IMF and emerging markets may not be able to wait for China forever.