Don’t Stop Believin’: The Inexorable Rise of German FDI in China

EU investments in China are being driven by Germany and its carmakers, deepening their dependency on the Chinese market while Berlin and Brussels pursue economic de-risking policies.

In 2022, when China was still paralyzed by zero-COVID lockdowns, we published a note entitled “The Chosen Few,” which highlighted the growing concentration of European foreign direct investment (FDI) in China among a small number of firms, countries, and sectors. Two years on, we take a new look at EU investment in China, assessing what has changed since Beijing abandoned its strict pandemic-era curbs and opened to the world again.

- Completed EU greenfield investment in China rebounded over the past year to reach a record high of €3.6 billion in the second quarter of 2024. This surge came despite growing geopolitical and economic headwinds that led US and Japanese firms to pare back their investments in China. European M&A in China, by contrast, has slowed sharply over the past two years.

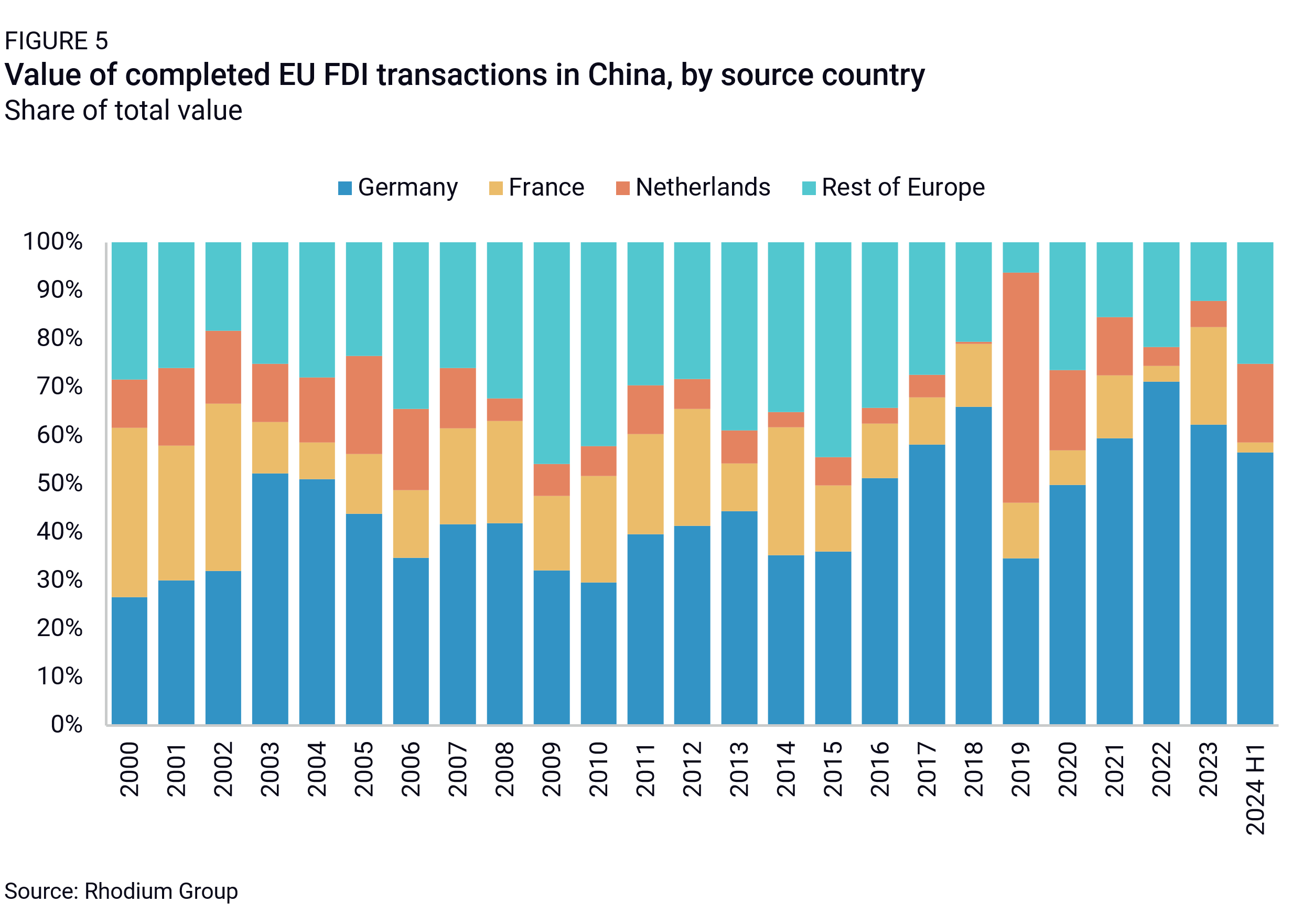

- To a greater extent than ever before, EU investments in China are being driven by Germany and its carmakers. German FDI made up 57% of total EU investments in China in the first half of 2024, 62% in 2023, and a record 71% in 2022. This was driven by auto-related FDI, which has accounted for roughly half of all EU investment in China since 2022.

- These investments are deepening the dependency of some of Germany’s largest companies on the Chinese market at a time when economic de-risking from China is a stated policy goal in Berlin and Brussels. As we saw in October, when the German government voted against EU duties on electric vehicle imports from China, these deepening ties can have a major influence on Germany’s policy toward China. This is likely to become a growing source of tension within the EU and between Europe and the United States.

- Several multi-billion-euro investments were announced in the first half of 2024, meaning that completed EU FDI levels are likely to remain high through the end of the year and into 2025. But these levels will probably come down in the years ahead. Much of the EU’s recent investment in China has been driven by a push to localize production, in part to insulate China operations from geopolitical tensions and trade barriers. Once this defensive capacity is built up, and in the absence of a more positive economic outlook, EU investment in China is likely to slow.

Record high

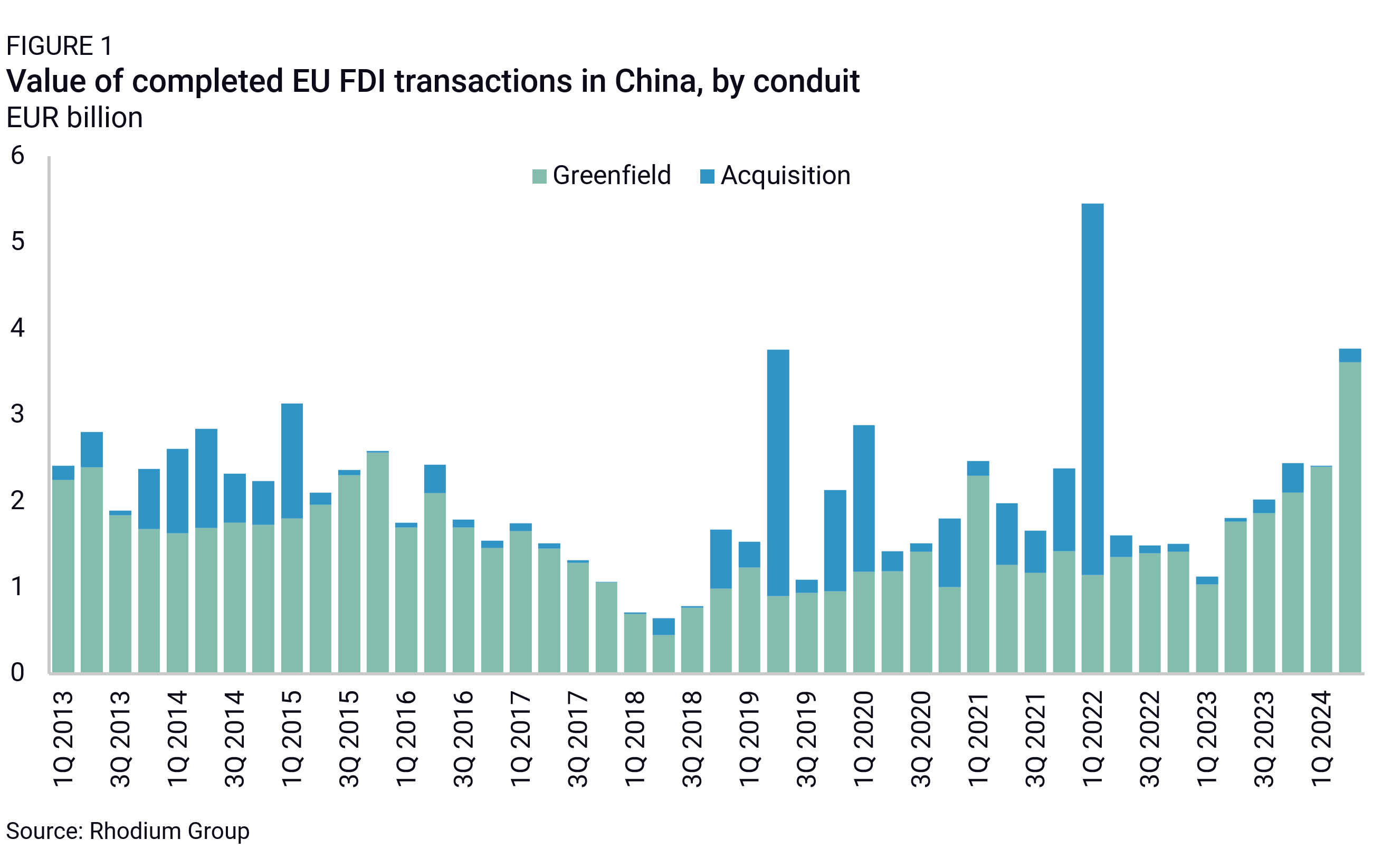

EU FDI in China is growing again after a steady decline between 2015 and 2018 and a period of high volatility between 2019 and 2022 due to several big-ticket acquisitions (Figure 1). Since the first quarter of 2023, European investment in China—including both greenfield investment and acquisitions—has increased rapidly and continuously, reaching €3.8 billion in the second quarter of 2024. This was the second-highest level of the past decade, bringing EU FDI closer to levels seen in the early 2010s—a period of persistently high EU investor interest in China.

The increase is even more striking when looking at greenfield investment, which took off in the past couple of years to reach €3.6 billion in Q2 2024, the highest quarterly level for EU greenfield FDI in China on record. This was not a one-off: EU greenfield FDI has averaged €1.8 billion per quarter since 2022, up from €1.25 billion on average over the previous three years (2019-2021). The growth was much less pronounced in terms of transaction count (22 deals per quarter on average between 2022 and H1 2024, compared to 20 per quarter between 2019 and 2021), suggesting that individual greenfield investments have grown much larger recently.

Our estimates likely understate the true value of European FDI in China. We identified roughly 80 investments over the past two years whose values were not disclosed (and therefore not included in our total value estimates). This suggests that the actual level of EU FDI could be much higher. Against a backdrop of heightened political and media scrutiny around European FDI in China, it is also possible that fewer transactions are being publicly disclosed. Moreover, a greater share of foreign investment may involve brownfield capacity expansions, and deals financed through reinvested earnings—both of which can be difficult to track in a comprehensive manner. Finally, our methodology tends to focus on larger deals (typically over €1 million), with the potential to underestimate small and medium enterprise investments on the ground.

The rise in EU FDI in China has come despite a dearth of M&A deals, with average quarterly M&A activity down 30% between 2022 and H1 2024 relative to the three years prior. In the second quarter of 2024, M&A activity fell to just €160 million. As outlined in our “Chosen Few” note, this sets China aside from usual patterns of EU investments into large, advanced economies, which tend to be dominated by M&A.

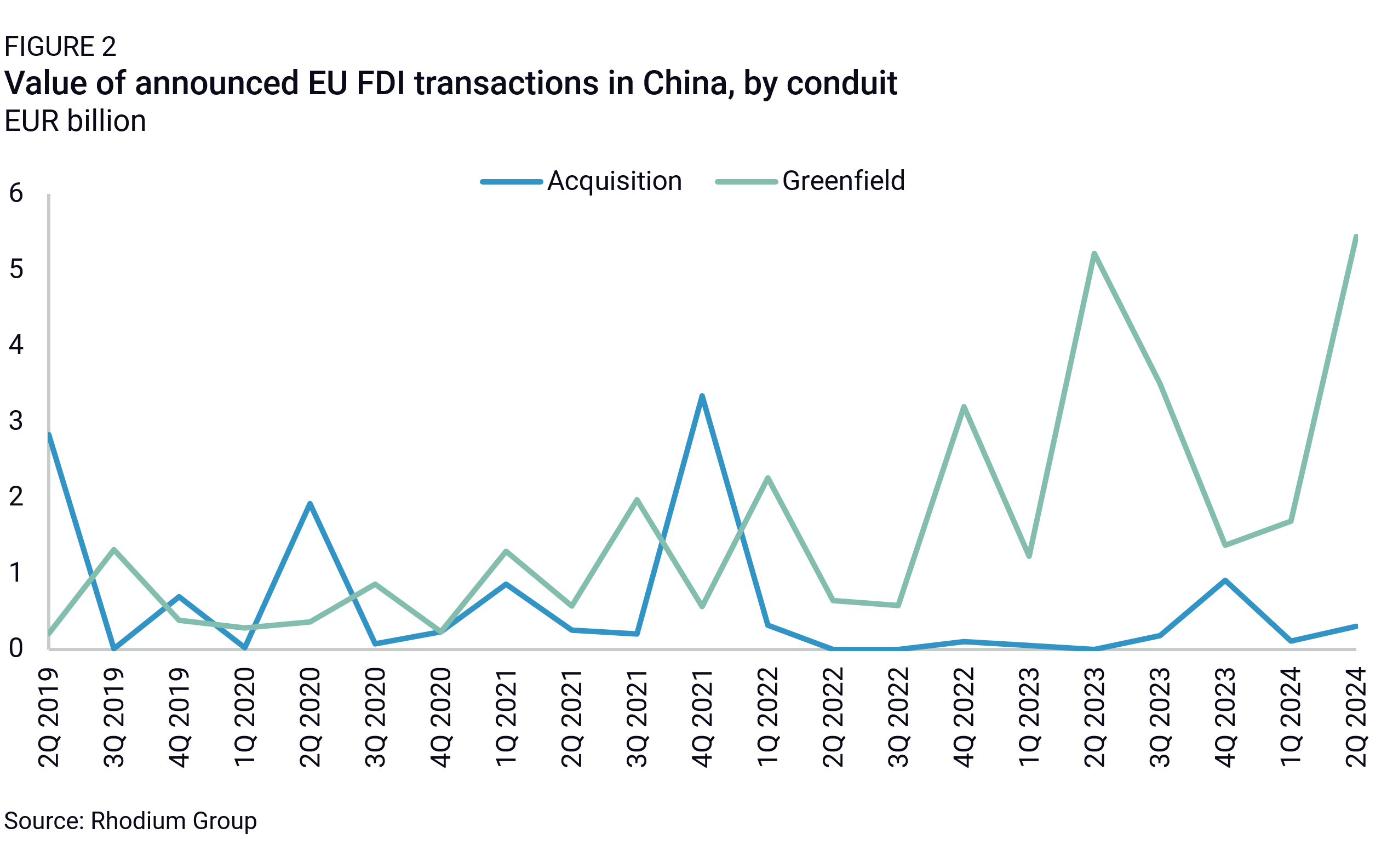

Completed EU FDI in China is likely to remain at high levels over the coming year. Our tracker of newly announced FDI shows a marked uptick in Q2 2024 to €5.74 billion, the highest level of the past five years. Not all announced investments will be finalized, but they point to a continued rise in EU FDI into China through the end of 2024 and into 2025.

A European puzzle

The strength of European FDI in China is surprising. China’s business environment is becoming ever more challenging for foreign companies, as underscored by the European Chamber of Commerce in China’s latest position paper. Business sentiment among European firms in China stands at an all-time low amid growing concerns about a lack of economic reform, increasingly politicized, securitized, and unpredictable policymaking, and faltering growth.

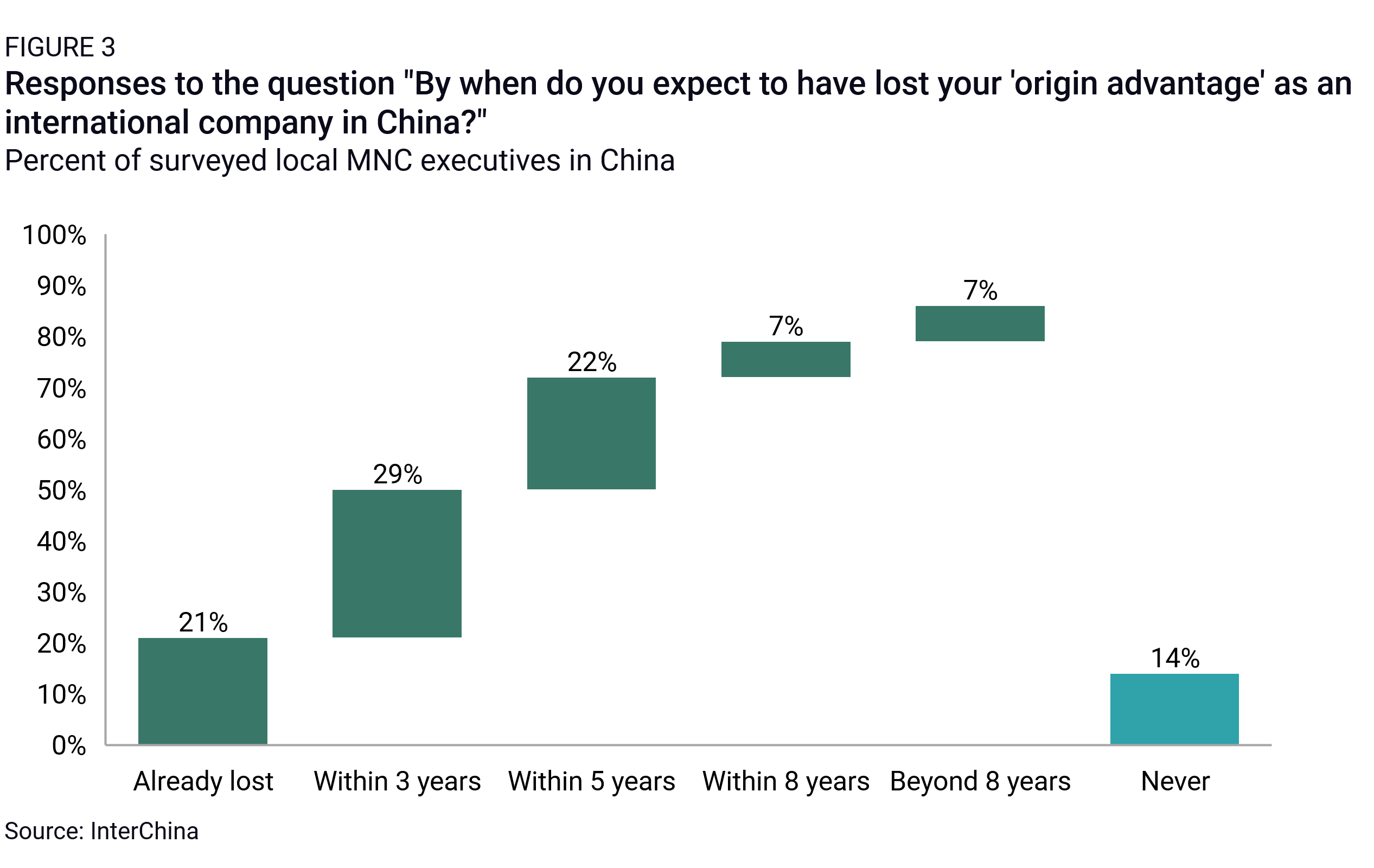

Foreign firms have struggled with China’s challenging policy and business environment for decades. But these concerns paled when set against China’s strong economic growth and the robust market share and high profit margins they enjoyed there. Today, this is no longer the case. Rhodium Group expects the Chinese economy to grow by 3-3.5% in 2024, well short of the government’s official 5% target. Chinese firms have also become fiercer competitors and are capturing market share from foreign peers. According to an InterChina survey of 271 foreign executives in China, roughly half are now convinced that their firm will have lost their “origin advantage” within the next three years (Figure 3). Profit margins are also getting tighter across a range of industries from automobiles to healthcare to machinery, adding to the pressure on foreign firms in China.

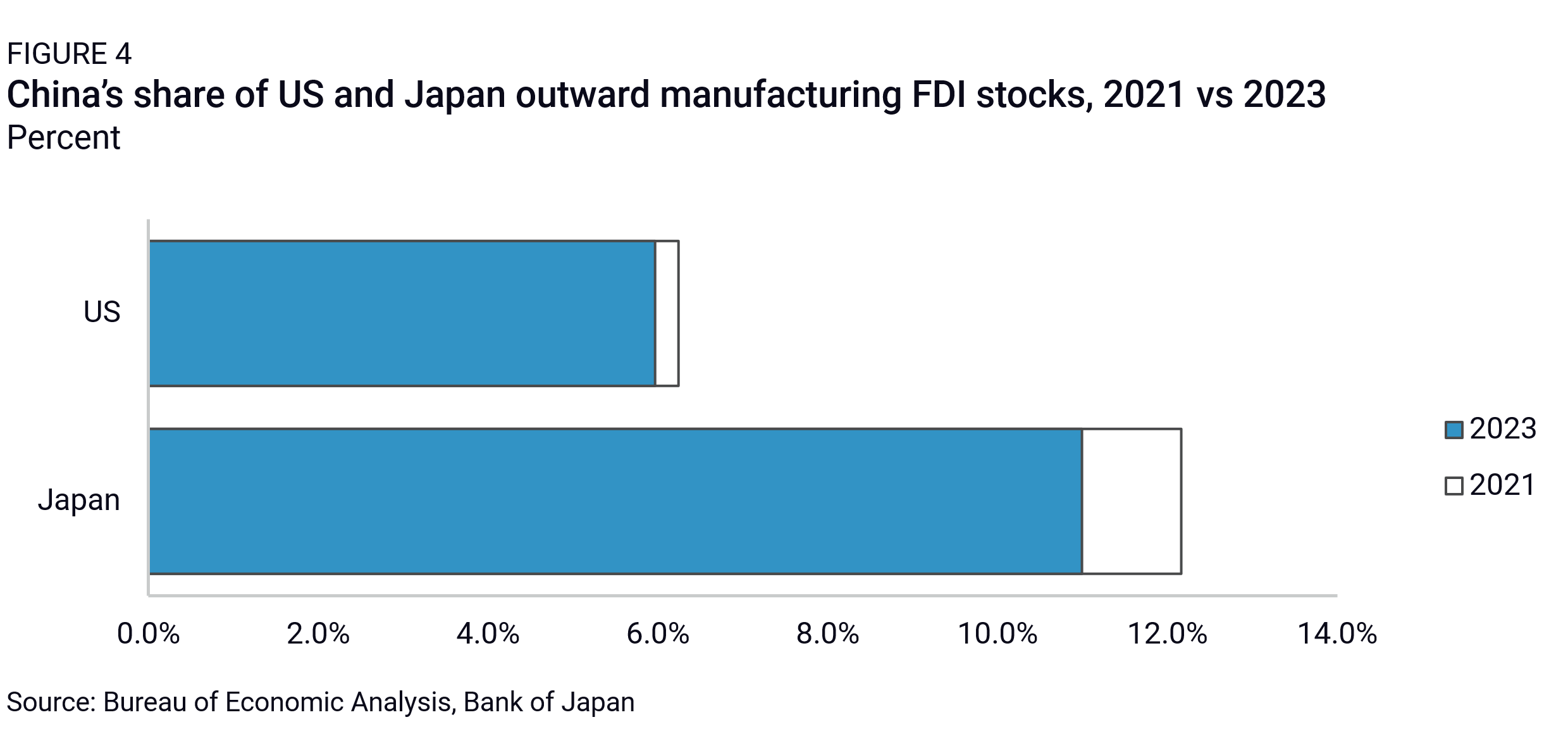

European businesses also face growing geopolitical risks as US-China competition intensifies and trade tensions between the EU and China mount, raising the risk of retaliatory measures by Beijing against European firms and products. The deteriorating environment has led firms from other countries, including the US and Japan, to rethink their investments in China and to diversify to other markets (Figure 4). German business leaders, by contrast, now point to diversification fatigue. After taking a close look at other markets over the past couple of years, many have determined that they can’t compete with China when it comes to costs, supply chains, and logistics. As a result, some are reining in plans to diversify away from China.

German cars still at the wheel

Why, then, has European FDI remained so resilient in recent years? The answer lies in the strength of German investment, which made up over 65% of EU FDI into China in the two-and-a-half-year period from 2022 through the first half of 2024, up from 48% in the period 2019-2021 (Figure 5). The top five European investors in China in 2023 were all German (Table 1). In comparison, the next three biggest EU investors—France, the Netherlands, and Denmark—have each represented between 7-8% of EU FDI since 2022. Together, the other 23 EU member states made up just 12% of EU FDI over the same period.

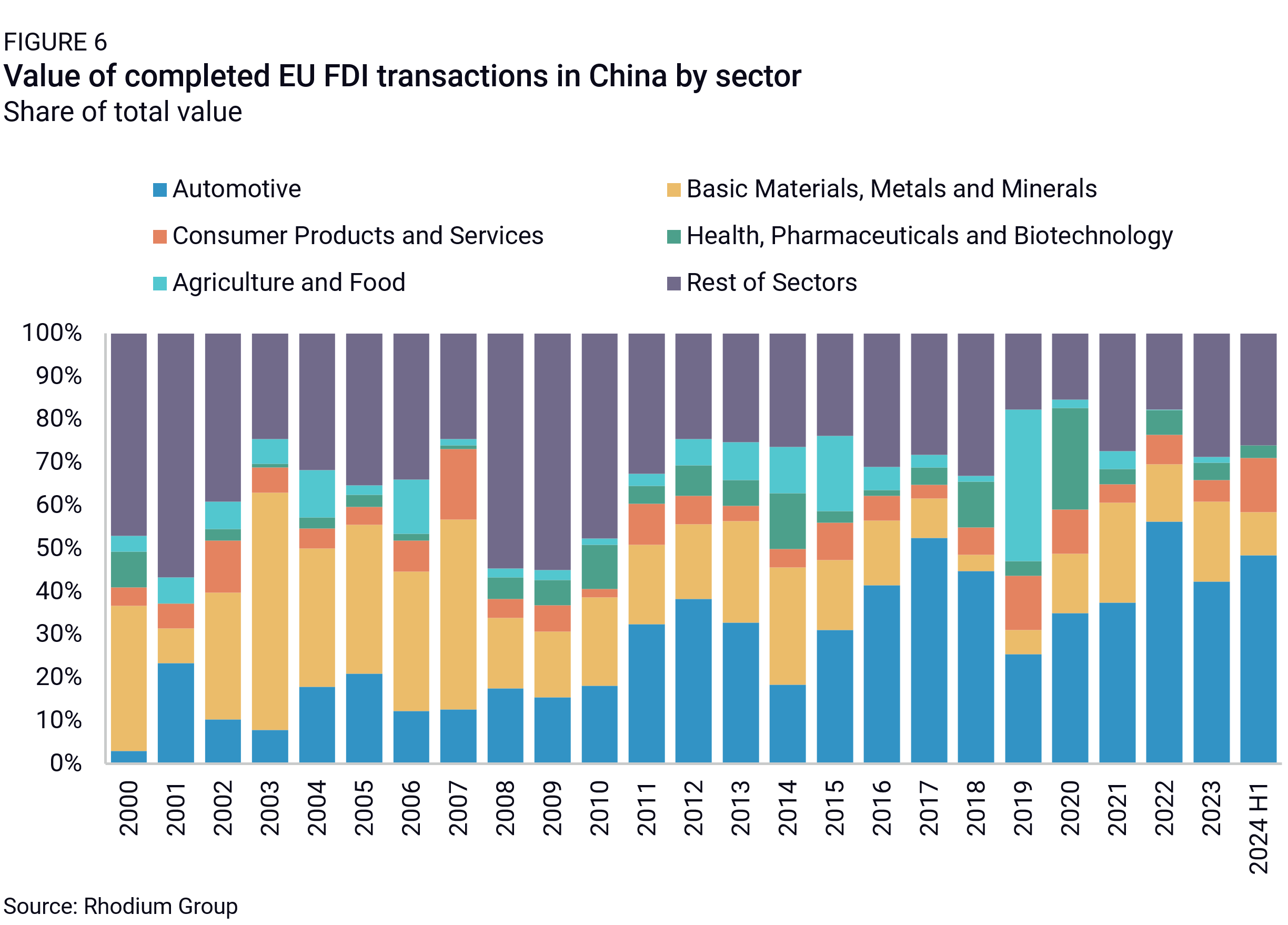

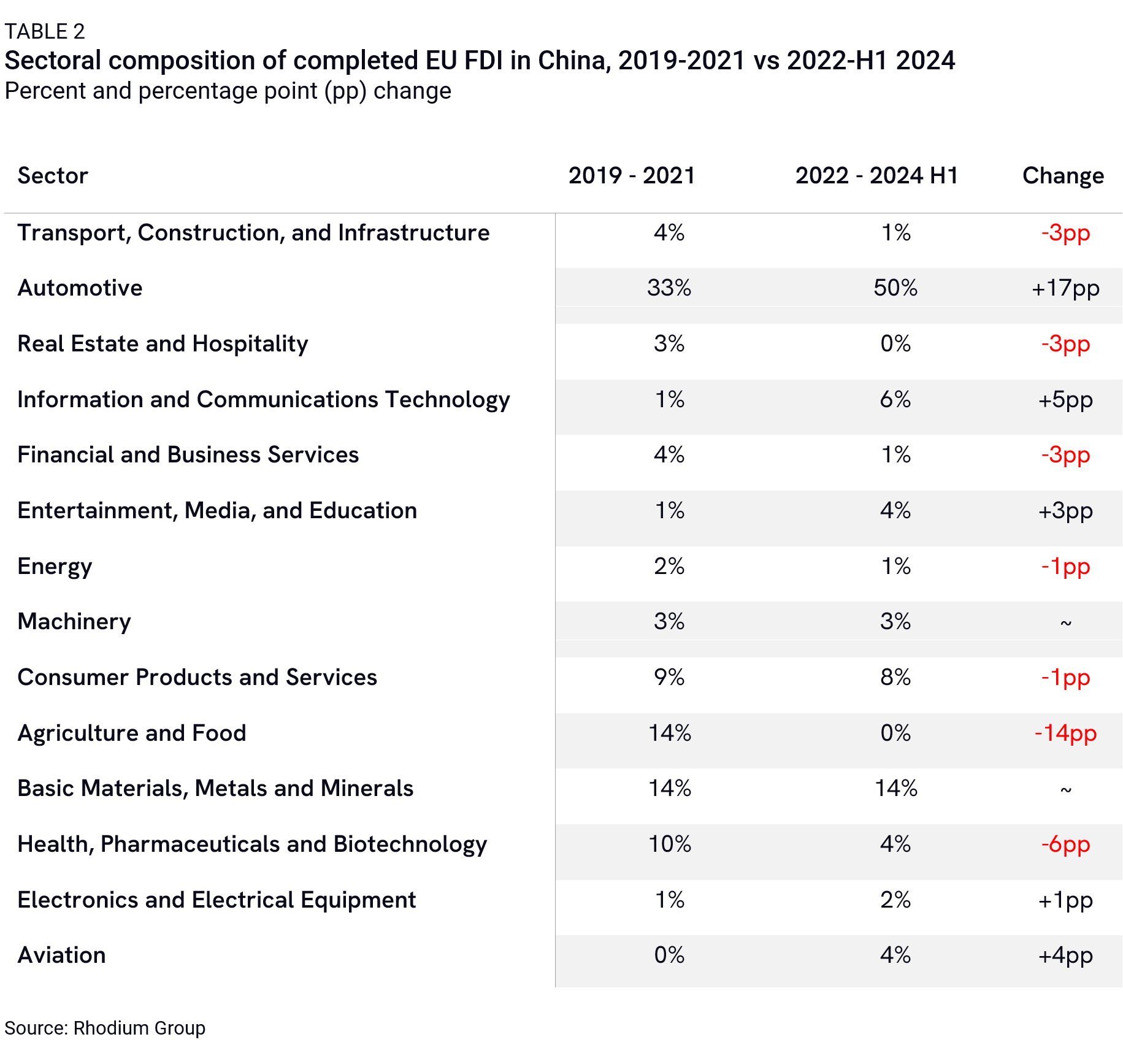

The strength of European FDI in China is also, to a greater extent than in previous years, attributable to the auto sector (Figure 6), which made up half of all EU FDI in China over the past two and a half years, compared to roughly a third in the prior three years (2019-2021). This share likely underestimates the sector’s true contribution as industries like chemicals, information and communications technologies (ICT), and machinery also provide key inputs to the auto sector. The joint venture between France’s STMicroelectronics and China’s Sanan Optoelectronics, for example, will manufacture silicon carbide devices for automotive and energy applications. BASF’s large-scale Verbund site in Guangdong will produce chemicals for the auto industry.

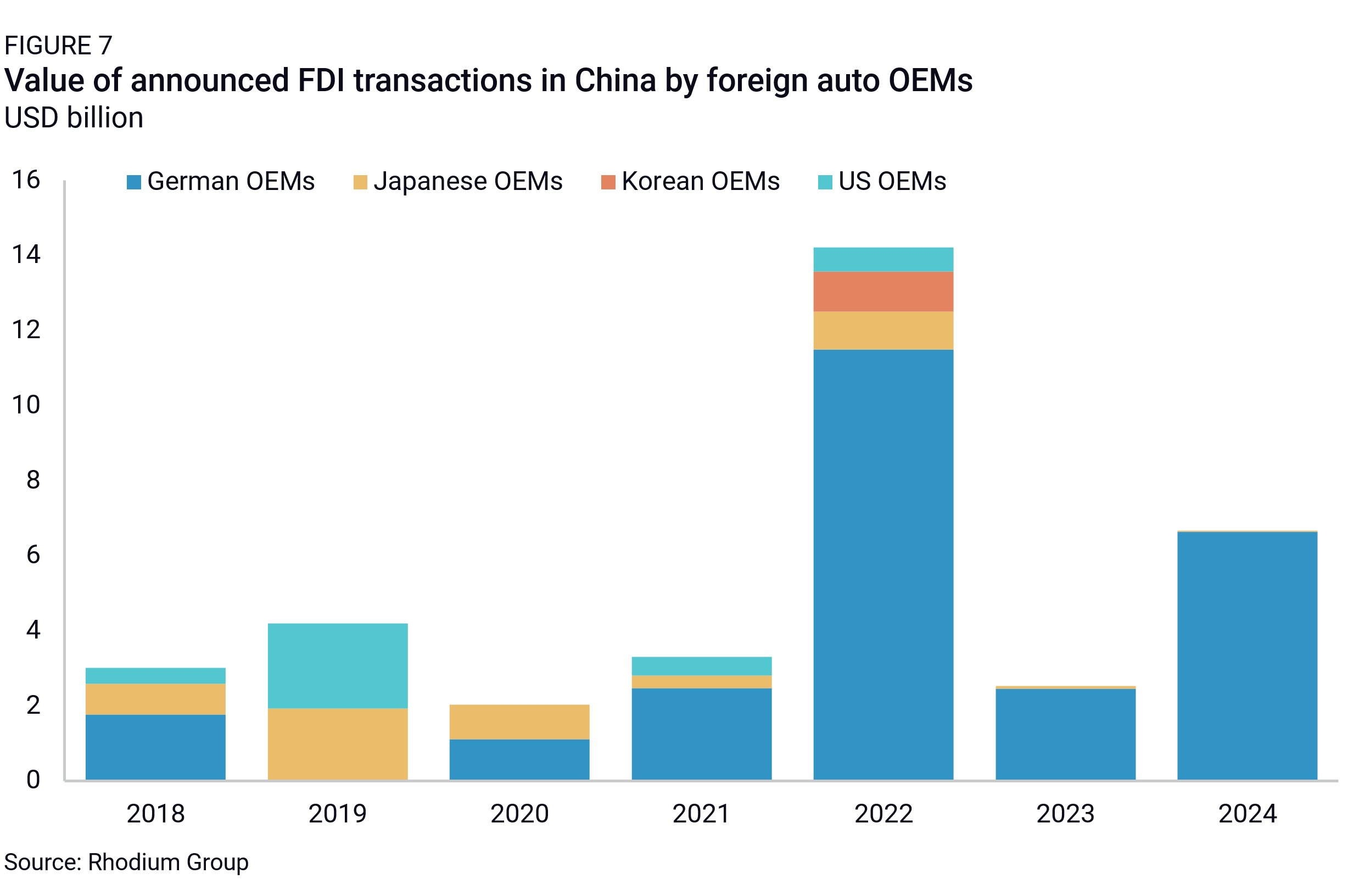

German OEMs, which represent the vast majority of EU auto-related FDI, are intensifying their investments in China as they try to defend their market share against growing competition from domestic electric vehicle (EV) manufacturers. Some have also taken advantage of China’s loosening of JV requirements: BMW and Volkswagen have increased their stakes in their JVs with Brilliance Auto and JAC Motor, respectively, from 50% to 75%. German OEMs are also upgrading existing production facilities to adapt to China’s quick transition to EVs, as well as increasing their local R&D footprint and sealing new technology partnerships.

This contrasts with Japanese, American, and other European counterparts, many of whom are scaling back or adjusting their approach to the Chinese market (Figure 7). Stellantis, for example, is downsizing its operations in China and focusing instead on strategic partnerships, like the one with Leapmotor. Nissan closed its newest factory in China in June 2024, only four years after it began production.

Why the difference? All foreign carmakers have seen their market share decline in China, but German OEMs have fared relatively better, especially in the premium segment. In 2022, they were still reporting record sales in China, while European, American, and Korean competitors were already on a downward trajectory. Many hope that by staying engaged, they can eventually emerge stronger in a less crowded market.

German OEMs may also be calculating that continued investment in China comes with few opportunity costs. China’s passenger vehicle market may be stagnating, but so are all other big markets other than India—a destination with less appetite for high-end German brands. The EU car market is shrinking, and the North American market is bound to become more disputed as Japanese and US carmakers pull back from China and double down on the US.

The behavior of German carmakers may also reflect the state of the political relationship between Berlin and Beijing. While the US and Japan have made de-risking from China a priority, Germany continues to send mixed signals to its companies. Germany’s China strategy, unveiled in 2023, emphasizes the need to de-risk, but German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has made clear that it should be left to companies to decide how to do so. Put simply, German firms face less political pressure to diversify away from China than US and Japanese companies do.

German auto suppliers, such as Bosch and ZF Friedrichshafen, are also doubling down on China, in part to support the upgraded facilities of German OEMs, but also to supply Chinese manufacturers as they gain market share over European rivals and are starting to export from China. Many are similarly ramping up their local R&D efforts to stay competitive in an environment where Chinese suppliers are rapidly closing the technological gap in areas like software, domain controllers, and sensors. In contrast to companies from other countries, they may also be hoping to leverage Chinese innovation for global markets.

Beyond cars

Several other sectors stand out as drivers of European investment in China. The chemicals industry represented 14% of European FDI by value in the period from 2022 through the first half of 2024, which is in line with historical levels (Table 1). Investment in consumer goods made up another 8% of FDI over the same period, followed by ICT at 6% and health and pharmaceuticals at 4% of total FDI value. Health and pharma saw a marked drop compared to previous years, having attracted 10% of total EU investment in 2019-2021. This is likely linked to the decline in European M&A activity in China—a key historical conduit for healthcare investment—as well as the relative restraint of pharmaceutical players on the back of cost-cutting policies and the slow pace of product approvals in China. In sectors like real estate, agriculture and food, transport, energy, and financial services, EU investments in China have virtually dried up.

Outlook

EU firms are facing a new reality in China—one involving stronger competition from local players, an increasingly bleak economic outlook, rising political pressure, and higher market barriers.

For some, notably the German carmakers, this more challenging environment has become, somewhat counterintuitively, a reason to double down on China. These firms are investing heavily to keep up with innovative local competitors—through acquisitions, R&D centers, and local partnerships—to try to protect revenues and market share. For example, they can play the localization and self-sufficiency cards to the fullest and try to shelter their China operations from geopolitical risks by reducing their exposure to trade restrictions through local production.

For others, however, China is no longer a no-brainer investment destination or a generator of high profit margins and rapid revenue growth that helps offset weaker demand in other markets and sustain jobs at home. By 2023, 38% of the 271 foreign executives surveyed by InterChina said they were considering divesting one or more of their firm’s assets or business units in China. And if German firms are removed from the equation, EU FDI in China totaled less than €4 billion in eight of the past nine years, after coming in at €5 to 7.5 billion in each of the preceding six years.

This reflects a yawning divide in how European firms view the China market, pitting a handful of German companies against a majority of firms from other EU countries. This divide could narrow in the years ahead. Once the current wave of defensive investments is finalized, and in the absence of an economic rebound in China, German firms may become more reluctant to expand capacity on the ground further.

Two developments could alter this trajectory. First, a trade conflict between Washington and Brussels could undermine growth in Europe and lead European firms to reassess their prospects in the US market and convince some to lean more heavily toward China. A crisis in the Taiwan Strait or South China Sea, or a step change in China’s military support for Russia could have the opposite effect, forcing even those firms that are heavily invested in China to reconsider their presence there. Some may hope for a government bailout should a crisis arise, although the German government has signaled that it would not come to the rescue. Others may consider splitting off their China operations as tensions rise.

Even without these extreme scenarios, the trajectory of Germany’s economic ties to China represents a major challenge for European policymakers. The dependence of German industry on the Chinese market, which for some big firms is only deepening, will continue to influence German policy toward China at a time when the European Commission is pressing ahead with an ever-broader de-risking agenda. Although the Commission succeeded in imposing duties on electric vehicle imports from China over the objections of the German government, it is difficult in the longer term to envision an EU China policy that is at odds with the perceived interests of its largest economy and member state. This tension threatens to build in the years ahead, as decoupling pressure from G7 partners, most notably the US, increases.