Through the Looking Glass: China’s 2023 GDP and the Year Ahead

China may see a cyclical recovery to perhaps 3.0-3.5% growth in 2024 as the property sector bottoms out, but structural slowdown will remain the dominant story for years to come.

Despite clear evidence that it was slowed down by unexpected economic headwinds this year, China will almost certainly claim to have hit its “around 5%” GDP growth target for 2023. The realities of a still-shrinking property sector, limited consumer spending, falling trade surplus, and battered local government finances mean that actual growth in 2023 was more like 1.5%. Looking ahead, China may see a cyclical recovery to perhaps 3.0-3.5% growth in 2024 as property bottoms out, although structural slowdown will naturally remain the dominant story for years to come.

2023 in Review

China started the year 2023 paradoxically. COVID had throttled the economy, but expectations were high for a boom after lockdowns were over and pent-up demand could flow. Beijing targeted “around 5%” GDP growth for the year. Forecasts from the IMF and OECD, as well as private sector economists, broadly endorsed that expectation. In December 2022, the World Bank wrote in its China economic update that “after an uneven growth performance this year, China’s economy is projected to recover in 2023.” By March, OECD economists opined in their Economic Outlook that household pandemic savings would drive growth to 5.3%. While acknowledging unresolved property risks, the IMF predicted 5.2% Chinese growth for the year.

In stark contrast to these high hopes, our December 2022 forecast was dark. We argued that actual growth was likely to remain stuck below 3%, while official reports would claim it was higher. In our view, the property sector was still far from bottoming out. Government spending would remain constrained by local debt burdens. Reopening would reduce the trade surplus as China’s services trade deficit finally picked back up due to travel abroad. Consumption had reason to be strong, but we argued that if China were to achieve growth near 5%, given the headwinds elsewhere, it would require heroic levels of spending by Chinese consumers. Given the signs of anemic income growth, household deleveraging, elevated unemployment, and the anxiety from slowing construction, we could not see how such high levels of household spending would be possible.

By mid-2023, the evidence of slowdown was abundant. The property sector was still shrinking, with the list of defaults among private developers growing longer. The lagged effect of falling land sales revenues left local governments without needed revenues for existing obligations or stimulus. The elevated trade surplus China enjoyed during the pandemic shrank. Most importantly, China’s consumers were not spending nearly enough to achieve official growth targets. By October, officials were alarmed enough to authorize one trillion yuan in special treasury bonds to boost local government investment, though most of that would not land until 2024. The list of anecdotal signs of trouble kept piling up right through the year.

Yet through this steady parade of slowdown indications, GDP forecasts barely moved. Official quarterly GDP statistics and monthly retail sales statistics were enhanced early in the year by tweaks to prior period data that fluffed up current figures. And that, in turn, was good enough for the international organizations tasked with providing independent validation and for most of the sell-side research economists advising investors.

According to China’s own numbers, its economy is on track to reach 5% growth in 2023. To be sure, there are bright-spot industries such as electric vehicles (EVs) that are outpacing the rest of the economy. But when Beijing publishes a 5%+ 2023 GDP growth number next month, it will be irreconcilable with evidence of general malaise and reactive policymaking that has piled up all year long.

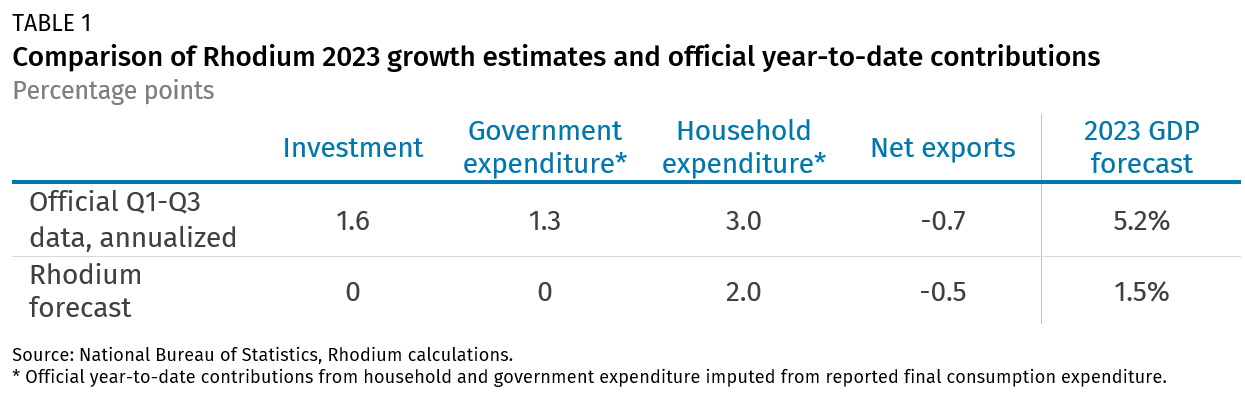

How then can we offer perspective on 2024 growth, when we need a believable 2023 baseline to do so? This year, because the official numbers are too shaky, we offer our own view on the 2023 baseline before looking ahead to 2024. As in previous years, our analysis builds from four expenditure-side GDP components: business investment (gross fixed capital formation), government spending, net exports, and household consumption.

2023 Investment

Official contribution to GDP growth through Q3, annualized: 1.6 percentage points (pp).

Rhodium 2023 estimate: ~0 pp.

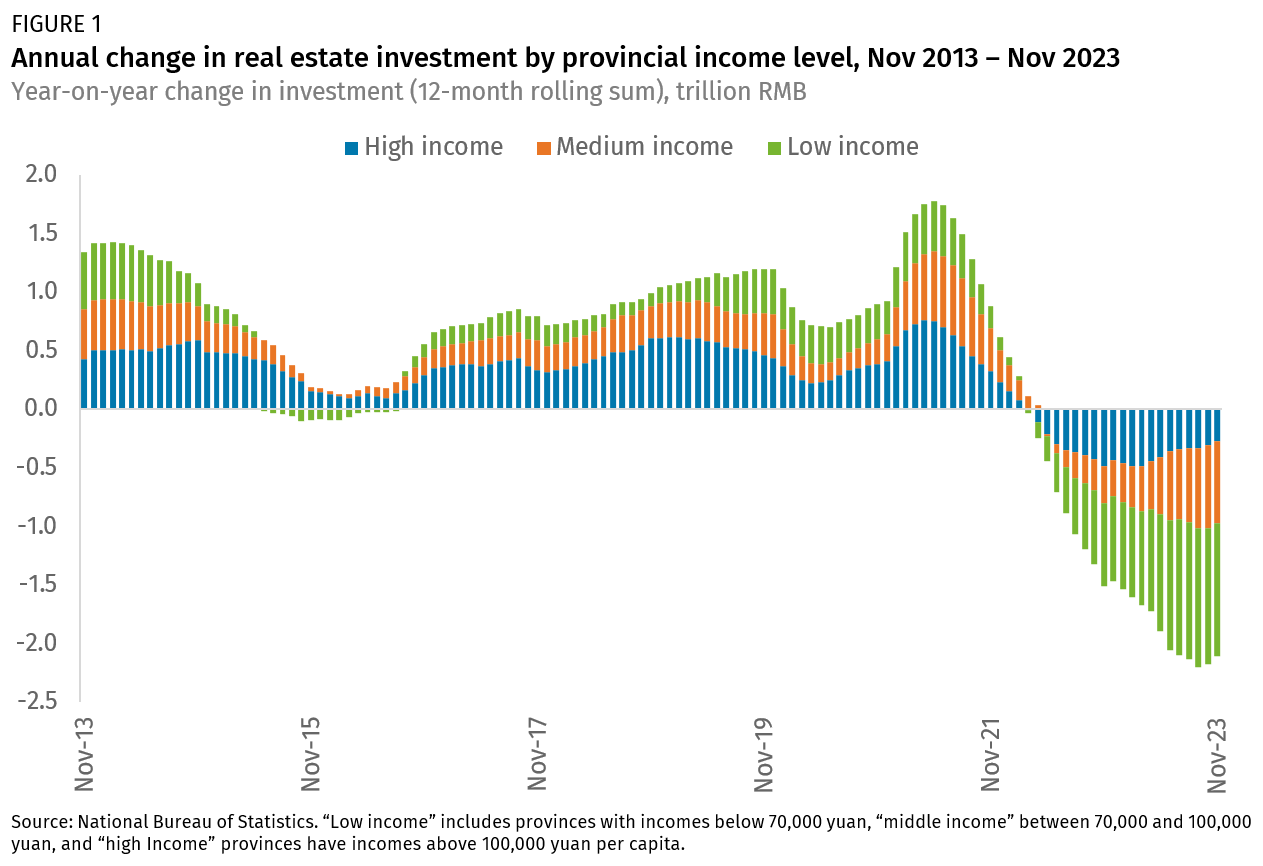

The headline story of 2023 was the continued contraction in the property sector. At its peak, the broad property cluster represented nearly a quarter of all activity in China. In March 2021, China was building new residential property at a rate of 1.71 billion square meters per year. By December 2022, that had fallen by half, to 881 million square meters. From January to October 2023, it fell another 20%, to 699 million square meters, where it may be bottoming out. Based on reporting from the National Bureau of Statistics, in the period year-to-date through November, China invested RMB 2 trillion less in the real estate sector than it did in the same period in 2022—a drop equivalent to 1.6% of China’s GDP. All things equal, some other investment activity would have to fill that hole just to avoid negative growth in investment this year, let alone paint a positive picture.

Could anything offset this property contraction? Officially, private sector investment was also negative so far in 2023 (although this includes some of the decline in real estate investment), dropping by 0.5%. Infrastructure investment rose by 5.8% so far this year, but has slowed late in the year amidst broader constraints on local government investment from high debt levels (see the fiscal discussion below). Other investment proxies are also weak. China saw net disinvestment in the foreign direct investment channel in the third quarter of 2023 for the first time on record (since the 1990s), reflecting firms moving more capital out of China than bringing new money in. Chinese firms are stepping up outbound investment too, as they seek growth. Stock market barometers such as the CSI 300 and the external MSCI China index fell steeply in 2023, reflecting sour expectations about the outlook.

Beijing’s numbers from the first three quarters of 2023—the latest official figures available as of writing—suggest that investment is on pace to contribute 1.6 percentage points to growth. Consider the last time that investment made a similar contribution, in 2019, when investment added 1.7 percentage points to results. The question is whether 2023 investment growth was remotely like 2019, when property investment grew by 10% and the CSI 300 index grew 36%. Does anyone believe that to be the case? No one we know. Given the drag from the property sector slowdown and signals of weak business investment, we surmise a 0% 2023 investment contribution to GDP growth.

2023 Government Spending

Estimated contribution through Q3 based on official data, annualized: 1.3 pp

Rhodium 2023 estimate: ~0 pp

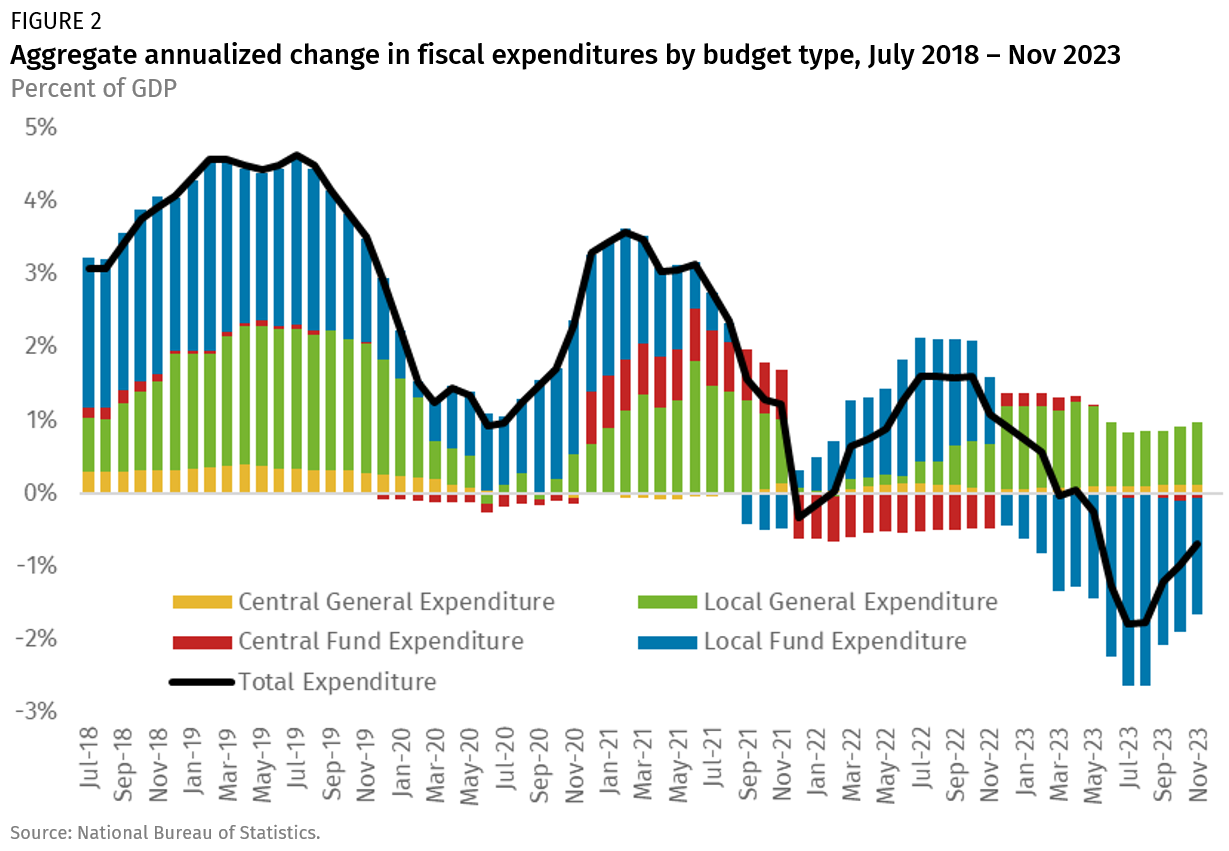

2023 started with a modest rise in the targeted fiscal deficit, from 2.8% of GDP in 2022 to 3.0%. But falling property activity decimated local government revenues as land sales fell sharply. And while the property-related hit to local government finances had the largest impact this year, the decline is structural—government revenues as a share of GDP peaked in 2015 at 22.1%, falling to 16.8% by last year. Rising local debt has meant a growing share of limited revenue being used for debt service. In our survey of 205 cities’ financial data from 2022, half were making interest payments on debt accounting for 10% or more of available fiscal resources.

According to official data, China is on pace to report a 4.3 percentage point contribution from combined household and government consumption in 2023, extrapolating from official quarterly data which does not separate the two. Historically, 70% of consumption in China comes from households, and 30% comes from government spending, which would imply around 1.3 percentage points contributed by government spending through Q3 this year. But as shown in Figure 2, a more complete picture that includes local fund expenditures shows that the year-on-year change in fiscal spending has been negative all year. The best that Beijing could realistically report for the contribution from government expenditure would be closer to zero percentage points, rather than the 1.3 percentage point contribution that is implied through Q3.

2023 Consumption

Estimated contribution through Q3 based on official data, annualized: 3 pp

Rhodium 2023 estimate: 2 pp

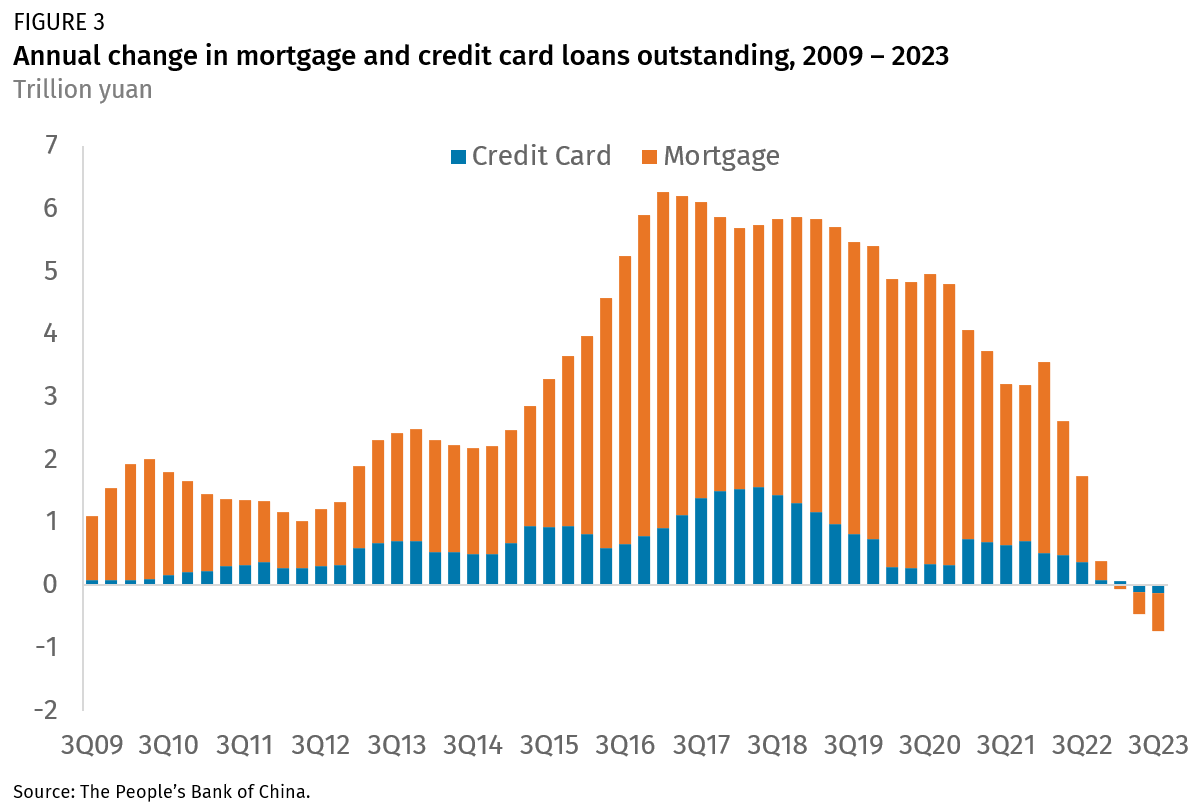

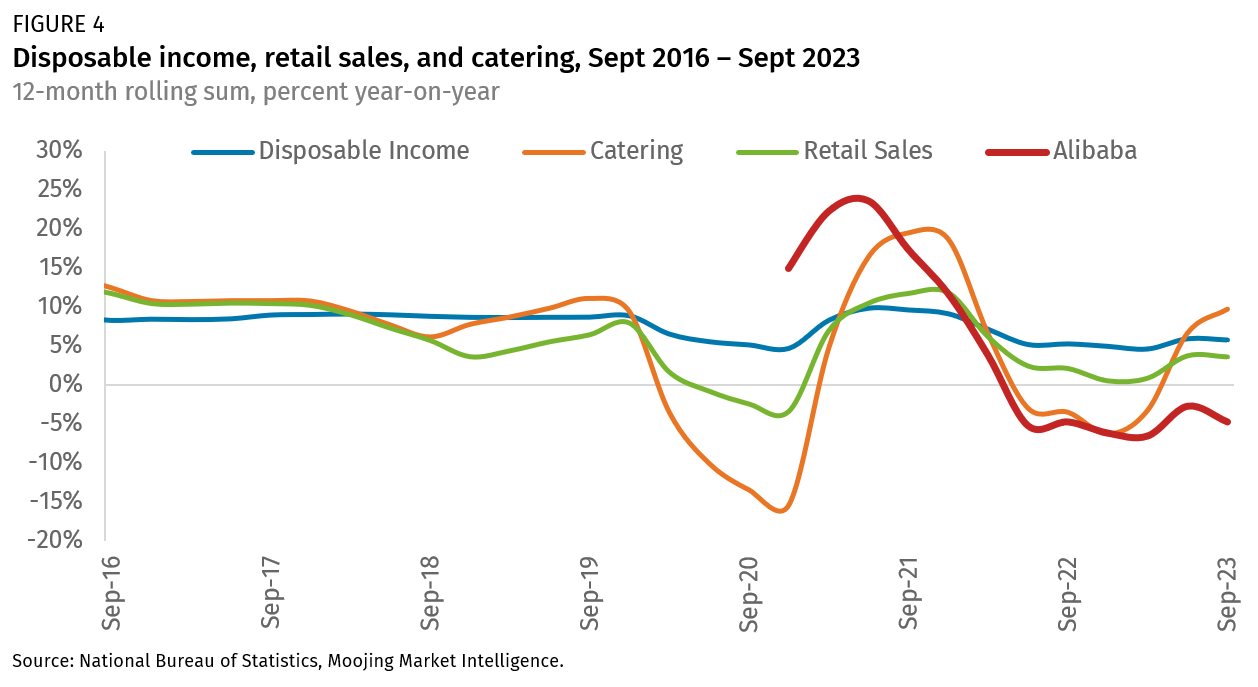

In January 2023, many analysts argued that Chinese consumers had built up savings and were ready to spend. In reality, the rise in household deposits did not reflect significant growth in actual savings, but rather households shifting away from risky wealth management products to safer but locked-in time deposit accounts, with most of these transactions occurring among a small share of high-income households. The bulk of Chinese earners faced slowing income growth from zero-COVID disruptions, the property crunch, a crackdown on high-growth technology employers, and weakening export manufacturing activity. Rather than increasing consumption, Chinese households were deleveraging in 2023. At the end of the third quarter, outstanding credit card loans contracted by RMB 130 billion compared to a year ago, and mortgage loans had declined by RMB 600 billion. The national decline in property values continues to weigh on household confidence.

As with government spending, Beijing has not yet published an official estimate of consumption that breaks out household spending so far in 2023. But extrapolating from the 4.3% year-to-date contribution from combined government and household spending and historical trends, it is a fair bet that when China reports the contribution of household consumption to 2023 GDP, it will be around 3 percentage points.

This is probably not too far off the mark. Consensus estimates for retail sales growth in 2023 are 7.6%, rising in December from 7.2% year-to-date through November. After accounting for inflation and data distortions early in the year stemming from revisions to retail sales totals for some months in 2022, retail sales growth would suggest a growth contribution from household consumption no higher than 2 percentage points.

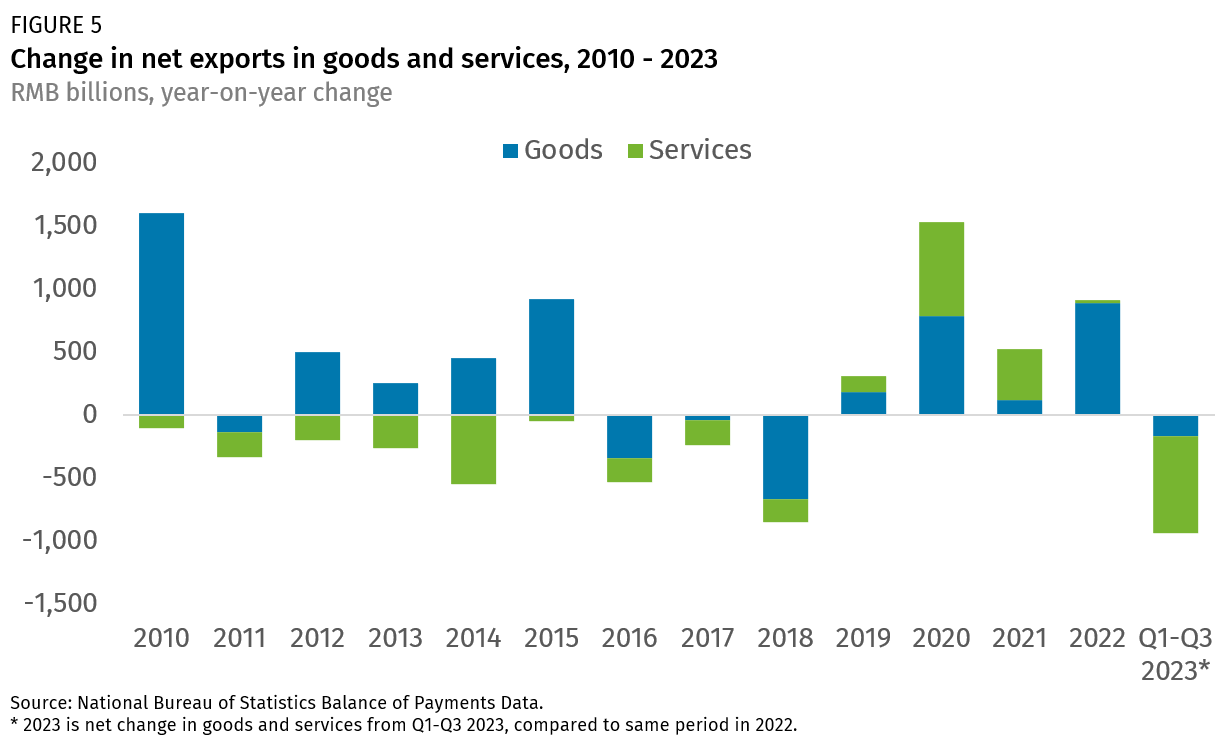

2023 Net Exports

Official contribution through Q3, annualized: -0.7 pp

Rhodium 2023 estimate: -0.5 pp

After four years of an expanding trade surplus contributing to China’s GDP growth, net exports contracted this year—even in official data—as China’s services imports, particularly tourism, resumed. China’s net imports in services in the first three quarters of 2023 was RMB 1.19 trillion, up from only RMB 412 billion in the same period in 2022, according to balance of payments statistics.

Growth in China’s annual goods trade surplus has flattened out. Chinese goods exports through November grew only 0.5% in Chinese yuan terms, according to Chinese customs data. Goods imports fell at a faster rate, but nowhere near the level needed to offset the services trade deficit. Net exports will be a negative contributor to GDP growth in 2023 (see Figure 5), probably in the range of -0.5 percentage points.

In sum, 2023 started with a great deal of optimism for an economic rebound. Despite the abundant evidence that the recovery was falling short of expectations, Beijing has not wavered in insisting that the economy is still on track. In our view, growth in 2023 was probably closer to 1.5% than the “around 5%” that Beijing will report in January. As long as official data in China remains subordinate to the official narrative, good economists will differ in their estimates. What is indisputable, however, is that China is in the middle of a structural slowdown that led to far weaker activity than most expected in 2023, and that will continue to affect the outlook as we look ahead to 2024.

Looking Ahead to 2024

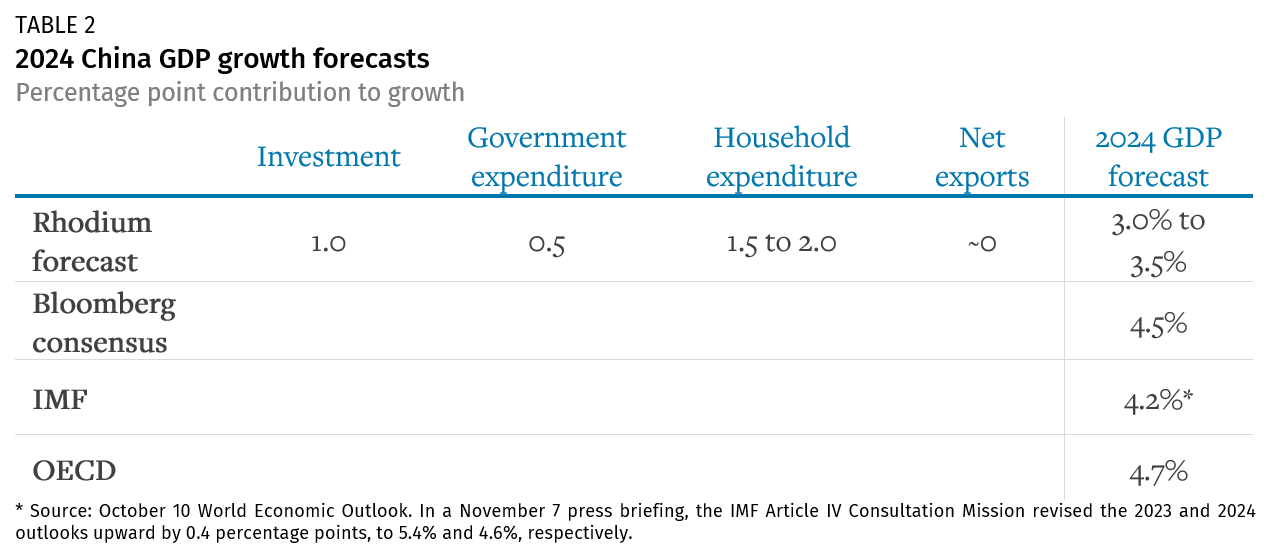

In 2024, China will see a modest cyclical recovery in some areas amidst an ongoing structural slowdown. The Bloomberg consensus estimate is for 4.5% growth in 2024, down from 5.2% in 2023. We believe growth will be stronger next year relative to 2023, based primarily on a cyclical recovery in the property sector. However, the structural issues left unaddressed in 2023 will continue to drag down China’s potential growth.

2024 Investment

Rhodium estimate: 1 pp

As in 2022 and 2023, the investment story to watch in 2024 is property. Last year’s downside surprise to consensus forecasts was due to the deepening property contraction. Next year’s surprise will likely be the sector bottoming out, and even making a small contribution to growth.

Based on demographic fundamentals, we estimate long-term equilibrium for property sector activity between 550 million and 750 million square meters of construction per year. In November 2023, new residential housing starts increased for the first time in 31 months. On an annualized basis, there are now 701 million square meters of new construction, within our range of long-term equilibrium. Property activity is now less than half of what it was at its peak in 2021. It is unlikely to ever return to that level, but at least it will no longer be a meaningful drag on the economy in 2024.

A broad investment recovery is unlikely. Beijing is dealing with local government financial stress by forcing banks to absorb non-performing LGFV debt. Banks’ profitability and their ability to lend to productive firms will suffer. While the government can—and will—support strategic industries, the Central Economic Work Conference (CEWC) readout admitted that overcapacity in certain industries is a serious 2024 challenge. Facing geopolitical realities, foreign firms are likely to continue diversifying their next investments beyond China. Putting this all together, and assuming a modest property sector rebound, we estimate a 1 percentage point contribution to growth from investment in 2024.

2024 Government Spending

Rhodium estimate: 0.5 pp

Given ongoing economic strains and policy disappointments in 2023, observers watched the December 11-12 CEWC for signs of more expansive fiscal stimulus. The conference statement mostly disappointed on that front. While the overall fiscal stance remained unchanged as “proactive,” the meeting highlighted the importance of maintaining fiscal sustainability rather than emphasizing new fiscal spending, as it did last year.

The hoped-for property bounce will not be enough to repair local government revenue shortfalls entirely. As we wrote in August, China has limited options to expand the fiscal base without imposing new taxes on sectors of the economy it wants to avoid hurting. Land sales revenues are paid with a lag, so weak 2023 land sales will weigh upon 2024 local government revenues. Ultimately, Beijing must scale back its fiscal ambitions and redirect spending to boost the productivity of human and physical capital. In the meantime, the central government balance sheet will be used to lift government spending back to the positive side of the ledger, which we expect to contribute perhaps 0.5 percentage points to 2024 GDP growth.

2024 Consumer Spending

Rhodium estimate: 1.5 to 2 pp

With income growth still slowing and continuing deleveraging ahead, 2024 household consumption should look much like it did in 2023. The latest urban depositor survey from mid-year 2023 showed that a rising proportion of households had seen their incomes fall quarter-on-quarter (15.1% in Q2 compared to 14.5% in Q1), and fewer households saw incomes rise (14.4% in Q2, down from 15.8% in Q1). Most households saw no change at all.

Household indebtedness remains high, and households are continuing to deleverage, reducing consumption. Household debt as a share of GDP is currently at 63.8%, which is around the levels the US saw shortly before the 2008 financial crisis.1

The current consensus among economists surveyed by Bloomberg for retail sales growth in 2024 is 6.0%, with inflation expectations around 1.4%. Assuming we see 4.6% real consumption growth in China next year, which is a reasonable expectation in our view, that would equate to a 1.5 to 2 percentage point contribution to 2024 GDP growth.

2024 Net Exports

Rhodium estimate: -0.25 to +0.25 pp

China’s COVID-era boost to the goods trade surplus ended in 2023, and its services trade deficit returned when people couldn’t travel, adding up to a negative contribution from net exports. The services deficit also camouflages capital flight, as people use tourism as cover to move money out of the country. By most anecdotal accounts, the urge to move assets abroad is stronger than ever amidst general uneasiness about the economic outlook and high interest rates abroad. One can easily imagine the services deficit expanding.

In goods trade, there are numerous headwinds for China’s exports next year. First, both the IMF and OECD forecast a modest global economic slowdown in 2024 to a level “well below historic average.” They foresee that slowdown to be even more acute in the developed economies that are the destination for most of China’s bright-spot exports.

Second, trade policy activism is rising in Europe, where policymakers are considering imposing countervailing duties (CVDs) to neutralize alleged Chinese EV subsidies. EV exports were a bright spot for the Chinese economy this year, particularly to Europe. A trade policy shift in the automotive sector would have immediate repercussions for one of China’s most promising industries. And while recent trade investigations have started with EVs, it is unlikely to stop there. In December, the European Commission launched an investigation into potential Chinese dumping of biofuels onto the EU market. Investigations into other sectors are likely to follow.

Finally, the combination of still-high US interest rates, low Chinese interest rates, and the fundamental desire for Chinese households to diversify their home-biased wealth overseas will continue to put pressure on the renminbi to depreciate. It is not hard to imagine a further 5-10% depreciation of the RMB against the dollar in 2024 (without making any assumptions about the global movements of the dollar). All else equal, currency weakness would make Chinese-origin products that much cheaper and thus price-competitive abroad, reducing the import propensity of Chinese consumers by making foreign products more expensive. If that were all that mattered, China’s goods trade surplus would be expected to rise somewhat as a result, likely through reduced Chinese imports rather than a further surge in exports. But myriad other factors—from trade policy to geoeconomics to business cycles—do matter, immensely so, and one cannot be confident how these factors balance out. Taken together, we see a contribution of net exports to growth that is basically neutral but limited in scope, between plus and minus 0.25 percentage points to China’s 2024 GDP growth.

2024: Putting It All Together

Putting these components together, our best guess for Chinese GDP growth in 2024 is 3.0 to 3.5%. Our view is out of consensus in three regards. First, we believe that China will grow more slowly next year than other mainstream forecasts imply (see Table 2). Secondly, while most forecasts expect growth to slow further next year, our 2024 baseline forecast of 3.0 to 3.5% growth represents a cyclical improvement relative to our 2023 baseline of 1.5%. Put simply, we think the economy next year will look better than last year, but nothing like the pre-COVID growth rates that an improvement on China’s official figures would imply. Third, while most forecasts expect the property sector to continue declining and government spending to step up, we foresee the reverse: fiscal policy will disappoint this year, and a cyclical recovery in the property sector will provide a small boost to growth, or at least no longer act as a drag.

If China does see a cyclical upturn next year, statisticians will face a strange dilemma. One theory to explain the unusual smoothness of China’s reported GDP over the years prior to COVID is that Beijing overstates growth in bad years and understates growth in good years. China is likely to set a growth target for 2024 a bit below whatever it reports for 2023. As the year goes on, cyclical indicators will point to rates of activity better than this year, but official data will show the economy slowing. International economic organizations that have set their forecasts lower than the target will progressively upgrade their forecasts over the course of the year to converge with China’s official number. The stories of how they got there will be different, but in the end, they’ll arrive at the same place.

How could our forecast be wrong? It is possible that the property sector continues to decline in 2024. While we have seen early signs of stabilization and are now around activity levels consistent with long-term fundamental demand, there is a real possibility that the correction in the property sector overshoots because of the financial distress among private developers, representing a downside risk to our 3.0 to 3.5% growth forecast. Household consumption risks also lean to the downside. The upside to household spending is fundamentally constrained by slowing disposable income growth, and a continued property market decline—or any number of economic shocks—could depress consumer sentiment.

Government spending could also surprise on the strong side. While China’s fiscal capacity is limited and initial signals from the CEWC suggested a conservative fiscal stance, Beijing could choose to boost growth by selling additional central government debt and giving money to the provinces to spend on infrastructure, for instance, rather than letting localities fund this spending with their own special revenue bond (SRB) issuance. Beijing may also deploy the central bank balance sheet more aggressively in order to fund fiscal stimulus, but this is likely to contribute to depreciation pressure on the RMB.

Conclusion

2023 will be remembered as the year China’s structural slowdown came into focus, beyond the fog of COVID. The debt-intensive growth model China had relied upon since the global financial crisis had run its course, and the burden of paying for past growth was constraining growth for today and tomorrow. In 2024, we may see a cyclical upturn given the severity of property distress the past two years, but structural slowdown will be the dominant theme for the coming years.

How Beijing responds to this reality is not a foregone conclusion. Though almost everyone inside and outside China is skeptical that China’s leadership and especially Xi Jinping would turn back to reform, we stand by our view that if economic activity gets bad enough, the Party would re-embrace market reform and opening rather than live without growth. While official data do not remotely suggest that conditions are bad enough to compel such a reversal, the state of the economy as described in this note probably is bad enough to justify real soul-searching. A big bang of economic policy change is not the base case for 2024, but it is a possible scenario that deserves attention.

Economic transparency is preconditional to healthy growth. The costs of China’s GDP omerta fall first and foremost on China itself: policymakers can’t resolve economic problems because doing so would publicly acknowledge that such problems exist. It also disincentivizes investment from global businesses. Most CEOs would much prefer a clear picture of slower Chinese growth than the uncertainty around misleading numbers that lead to policy errors.

For now, however, the official messaging on China’s economy remains controlled and ideologically rigid. Among the priority tasks listed in the official readout of the CEWC was “to strengthen economic propaganda and public opinion guidance, and to promote a positive narrative about the bright prospects for the Chinese economy.” For businesses and policymakers alike, this makes having a critical and objective view on China’s economy all the more important in 2024.

1. Estimate from the China Center for National Balance Sheets at the end of 3Q23. The People’s Bank of China estimate was 72% at the end of 2021.