ESG Impacts of China’s Next-Generation Outbound Investments: Indonesia and Cambodia

This report describes the changes in China’s global outbound foreign direct investment since 2017 and analyzes its implications for host countries from an ESG perspective

Executive Summary

This report describes the changes in China’s global outbound foreign direct investment (OFDI) since 2017 and draws on case studies in Southeast Asia to analyze the implications of this next-generation Chinese OFDI for host countries from an environmental, social, and governance (ESG) perspective. Based on new data estimating China’s regional investments from 2000 to 2021, we isolate four investments for case study and evaluate them using a multi-tier ESG framework and open-source reports. In Cambodia, we examine the massive Dara Sakor zone and a new tire manufacturing plant, while in Indonesia we examine a geothermal plant and a nickel processing plant for next-generation electric batteries.

Our main findings are:

- China’s global investment has seen tectonic shifts since 2017: Total investment has slowed down, likely taking an even sharper downturn than that shown in official data. The geographic focus has shifted from advanced economies to other parts of the world, especially Asia. In the 2010s, mergers and acquisitions (M&A) were the dominant mode of Chinese OFDI. However, greenfield FDI is becoming an increasingly important driver of China’s OFDI flows in recent years.

- Chinese investment in Southeast Asia has increased—counter to the global trend in China’s investment since 2016—and Chinese firms are becoming involved in new sectors. While China’s engagement in the region once focused on a handful of sectors, like real estate and light manufacturing, Cambodia and Indonesia are now seeing investments that fall outside those narrow industry bounds. Chinese firms’ investments in Southeast Asia are shifting from traditional sectors to more advanced manufacturing, processing of critical raw materials, and investments in technology and regional platform businesses. This mirrors shifts in investment in other regions, including Latin America.

- These new patterns are likely to continue, and host country governments should plan accordingly. As China’s economy matures and attempts to shift toward a new domestic model based on consumption and advanced technology, China’s firms may make new energy-intensive manufacturing investments overseas. As traditional industries move abroad, Chinese companies’ growing expertise in green technologies like alternative energy and electric vehicles will also enable new overseas investments in those sectors, but environmental effects on recipient countries will likely be mixed.

- The four ESG case studies covered in this report assess PT QMB New Energy Materials and PT Sorik Marapi geothermal plant (SMGP) in Indonesia and the Dara Sakor zone and CART Tire Co, Ltd in Cambodia. Each case was selected to highlight features of China’s outbound FDI in the region, such as new sectors of financial engagement, or Chinese firms’ new sustainability policies.

- Chinese companies are paying increasing attention to ESG concepts, formulating ESG policies and often producing reports covering firm-wide ESG activity. However, these reports often lack detail and metrics. Reports often omit company-wide metrics (like total carbon emissions) and project-level data. Instead, companies are more likely to report corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives like donations to local schools.

- Although Chinese firms operating abroad are often stereotyped as polluters with poor labor practices, there is substantial variation in the ESG practices and performance of the Chinese firms in our case studies. Each firm often performs satisfactorily in some aspects of ESG, such as community consultation, but does poorly in others. One exception is Dara Sakor, which rates poorly across almost all our metrics.

- Host country context in Indonesia and Cambodia matters for ESG outcomes. Our case studies support previous research showing that Chinese companies investing in Southeast Asian countries generally comply with host countries’ minimum requirements around ESG practices, including nominally conducting environmental and social impact studies, but usually they do not go further. Despite new voluntary “green investment” guidance from Chinese officials in recent years, in practice, the companies appear to adhere to China’s mandatory legal requirements, which require compliance only with host country regulations even if China’s domestic regulations might prohibit specific practices.

- Transparency remains a recurring challenge for the firms in our case studies. For our case studies, we could only verify the completion of environmental impact assessments (EIAs) or social impact assessments (SIAs) through secondary reports, and only for certain projects. None of the assessments were available via the internet. Only one project—CART Tire’s plant in Cambodia—had a publicly available feasibility study. This makes it difficult to establish assessment quality and analyze compliance with their recommendations—and sometimes even to ascertain if they were ever completed. A lack of additional quantitative data, including legally mandated disclosures, obscures the impact of investments on local areas, especially for projects that have small footprints or are part of larger zones.

- Our case studies observe recurring problems with pollution to waterways, marine areas, and protected land. Three of the Chinese investments we examine are located near sensitive or protected zones that do not appear to have received sufficient protections. In the case of Dara Sakor, the legal status of protected land did not prevent the development of protected areas, and similar dynamics appear to have been at play for Indonesia’s PT. SMGP geothermal power plant.

- Even projects that appear to promote “green” industry practices or support green technologies—like the battery materials plant and geothermal power station explored in this report—can fail to support good ESG outcomes at the project level. The battery material processing and geothermal power projects covered in this report exhibit poor environmental performance in one or more areas, highlighting the potential byproducts and risks of green technology development.

- China and host countries can do more to improve the capacity of almost all actors involved in Chinese overseas investment in Indonesia and Cambodia. These include consultants and contractors who may be responsible for implementing impact assessments, feasibility studies, and project activities. They also include Indonesian and Cambodian governments and regulatory bodies that may be under-resourced, lack clear legal authority or enforcement power, or are undermined by political input or interference on specific projects.

- Improving company-level disclosures and including meaningful quantitative and qualitative metrics is critical to improving ESG performance and facilitating new investment. If China’s government were to define clear standards and mandate disclosure (rather than relying on voluntary compliance), it would likely improve overseas ESG performance. More comprehensive coverage of Chinese companies’ activities abroad by commercial ESG data providers and public policy researchers would also help promote transparency and improve public accountability.

Introduction

China’s outbound investment has increased rapidly since 2010, establishing the country as one of the world’s largest sources of FDI. Southeast Asia, where China is now the largest single source of FDI, has felt this rise keenly. What began in the early 2000s as a slow trickle of investments in low-skilled manufacturing and natural resource extraction has evolved: Chinese firms have steadily expanded in the region, building regional supply chains, new markets for Chinese goods and services, and robust financial and services networks.

Like FDI from other countries, new investment presents both opportunities and risks for host countries in Southeast Asia(is defined in this report as the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN): Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Burma (Myanmar), the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.). China’s inflows have the potential to drive economic development and innovation, but they also present possible challenges to ESG outcomes. Even identifying where China’s firms are investing is a major data challenge, making it difficult to understand how host countries are being affected.

China’s outbound investment is changing rapidly. Significant developments in China’s economic priorities—from a new focus on “green” development to more restrictive policies on outbound investment—are shifting where and how Chinese firms invest in Southeast Asia. While previous investments focused on low-skilled manufacturing and resources, recent investments in the region include next-generation technologies from alternative energy and electric vehicles (EVs) to big data analytics and advanced manufacturing, while schemes like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) promote relationships across several contexts. Behind this shift, new Chinese economic policies emphasize a broader set of goals beyond simple economic returns. Now with several decades of experience operating in emerging markets, Chinese firms are paying increasing heed to ESG considerations. From the top down, China’s government has issued new green finance guidelines and policies to promote foreign investment sustainability, while from the bottom up, China’s firms are disclosing more about their global impacts and CSR initiatives as ESG principles become more deeply embedded in global markets.

This report examines the ESG impacts of China’s investment in Indonesia and Cambodia against the backdrop of these changes. First, we draw upon both official data and a novel transactions dataset tracking Chinese firms’ investments in both countries from 2000 to 2021. We review patterns of China’s investment in Southeast Asia and discuss the challenge of tracking Chinese financial flows to the region. We then review the current state of ESG, including China’s sustainability practices in both countries, and develop a framework for evaluating the ESG impacts of China’s overseas investments. Finally, we apply the framework to four recent Chinese investments across Cambodia and Indonesia to evaluate how China’s firms are applying ESG principles in practice.

A New Era of Chinese Outbound FDI

This section describes the evolution of China’s global investment trajectory and then reviews in greater detail China’s FDI footprint in Southeast Asia, specifically in Indonesia and Cambodia. Our overview draws from official FDI data as well as an alternative transactions dataset to address the gaps in official FDI statistics.

China’s Global Outbound FDI

Data on global FDI flows come with major caveats and limitations(- In national accounting statistics, cross-border investment flows are commonly separated into five categories: FDI, portfolio investment, derivatives, other investment, and reserves. Chinese investors have been active in Southeast Asia via all these channels, but this report focuses on FDI. ). One problem is that international statistics rely on national statistical agencies, many of which lack resources, manpower, or adequate training to collect detailed and accurate data on FDI flows and the operations of transnational enterprises. Compounding the challenge is firms’ use of holding companies and offshore vehicles to route financial flows; “roundtripping” (where companies route funds to themselves through countries or regions with generous tax policies and other incentives); and “transshipping” (where companies channel funds into a country to take advantage of favorable tax policies, only to reinvest in a third country). Accordingly, international FDI statistics (including those from United Nations [UN] agencies) often offer a frustratingly incomplete picture in which data are usually available only after years of processing delays, reported totals from home and host countries are inconsistent, and the investments are difficult or impossible to track after they pass through tax havens.

Tracking China’s overseas investment comes with additional challenges. First, two different government agencies are responsible for collecting outbound FDI statistics, causing data reconciliation and access issues. Second, China’s existing capital controls and burdensome regulatory requirements incentivize firms to underreport (or not report) foreign investments to evade capital controls and bureaucratic reviews. This means not all foreign investments may be reflected in official data. Lastly, because China’s firms almost always rely on offshore entities to structure their overseas investments, official data distort the geographical and sectoral distributions of Chinese investment. According to data from China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), an average of 64 percent of China’s outbound FDI flows from 2015 to 2020 were registered in either Hong Kong or tax havens such as the Cayman Islands and Singapore. From there, money flows to its ultimate destination—or, in many cases, back to China as part of roundtripping,” where flows end up funding domestic investments or returning back to the original investor. This means there can be substantial differences between what Chinese officials report on the outbound side and what host economies report receiving from China.

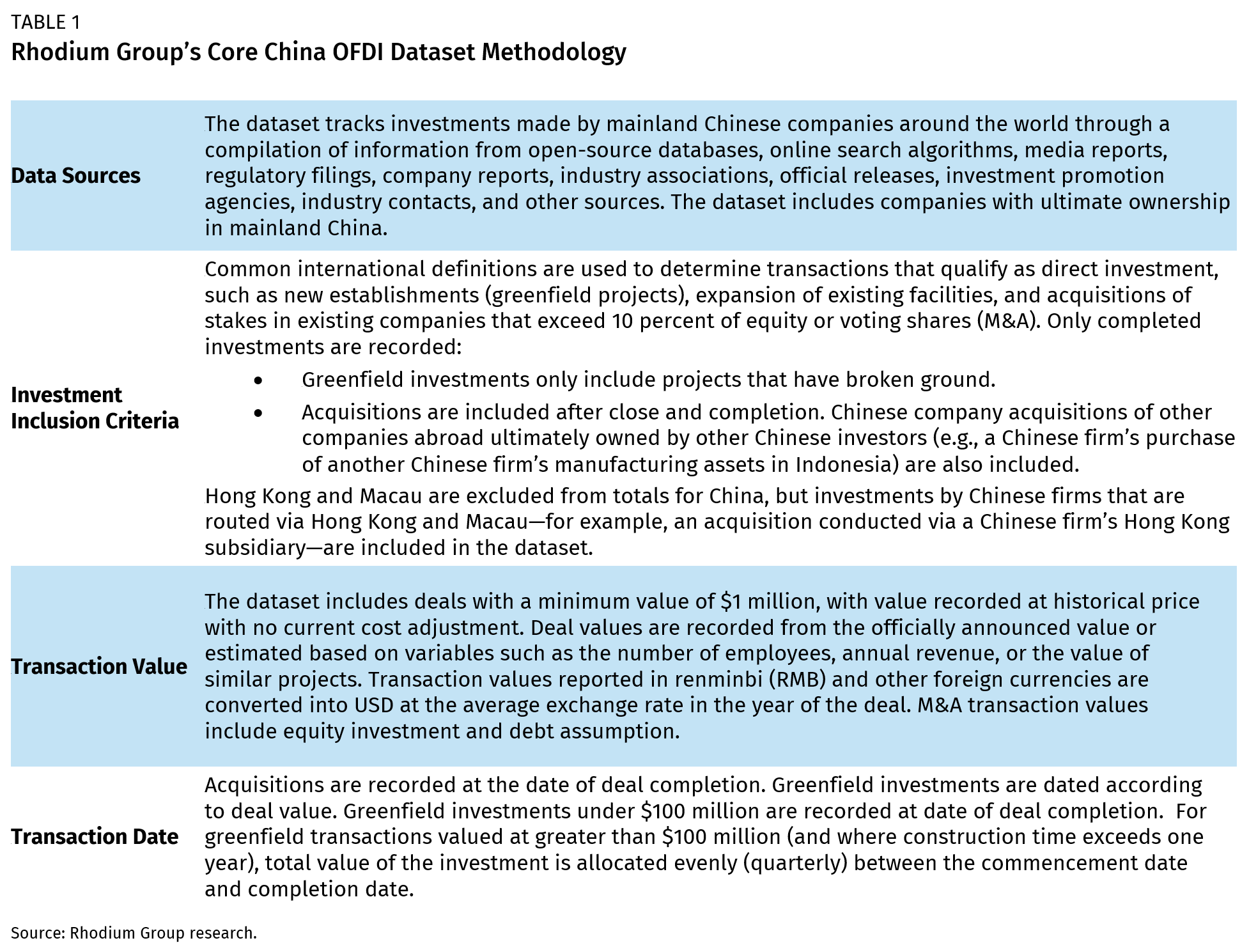

For these reasons, it is critical to consider various available data points to get a reliable sense of China’s investment trajectory and its FDI footprint in a specific region or country. In addition to official statistics from China and the host nation, it is important to consult alternative data that can shed light on the patterns of Chinese outbound FDI. One such perspective is a dataset compiled by Rhodium Group that collects and aggregates data on global acquisitions and greenfield investments by companies and investors from China with a value of $1 million and above (the Rhodium “Core China OFDI” dataset, Table 1). Such alternative transactions datasets are not directly comparable to those compiled using the traditional balance of payments (BoP) method, but they do avoid some of the existing problems—namely issues with time lags and passthrough locations—and permit a real-time assessment of investment trends.

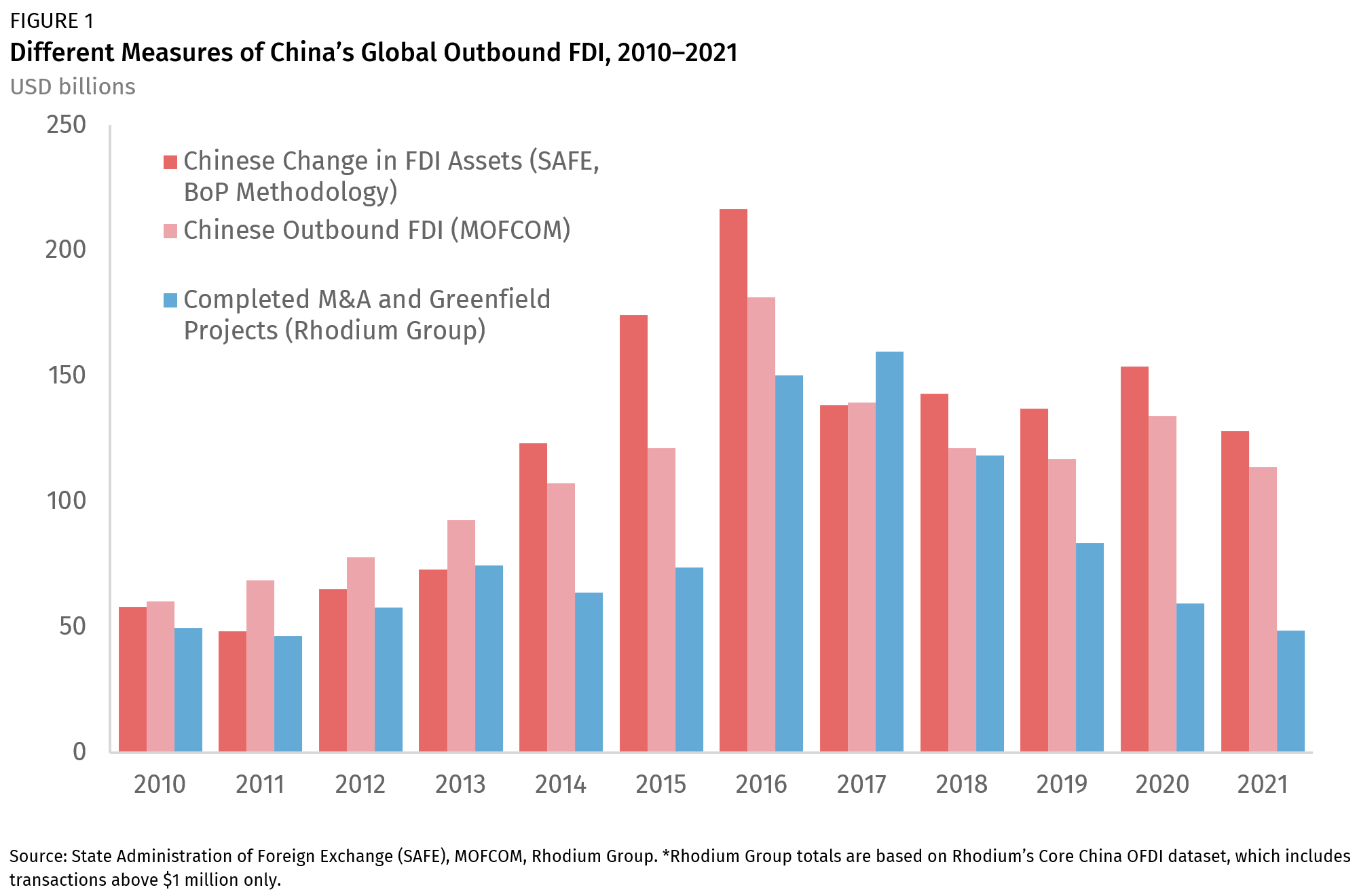

All available data sources illustrate a sea of change in China’s outbound investment trajectory in recent years. Since the mid-2000s, China’s global OFDI has grown steadily, reaching a boom in 2014 after Beijing liberalized outflows through the FDI channel. Beijing reversed this policy in late 2016 and initiated a crackdown on “illicit” flows in sectors such as real estate and gaming. The reimposition of capital controls and greater regulatory scrutiny abroad led to a significant drop in annual OFDI flows after 2016, but available data sources paint a different picture of the extent of the slowdown. The average annual outbound FDI over the last five years recorded in China’s official statistics only indicates a modest drop of about 21 percent from the 2016 peak, while alternative datasets show a much steeper drop, especially in certain types of transactions like M&A (Figure 1). Both official sources and alternative data show another drop in 2021, but official data suggest more stability than the alternative transactions approach.

Chinese FDI in Southeast Asia

In addition to a slowdown in overall investment, we are also observing a clear change in the geographic patterns of Chinese outbound FDI since 2016. Advanced economies that previously attracted large amounts of Chinese FDI in the form of M&A transactions—such as the United States, the United Kingdom, or Australia—have seen declining inflows since 2016, especially in sectors blacklisted by Chinese regulators and scrutinized by host country authorities under tightening investment screening rules.

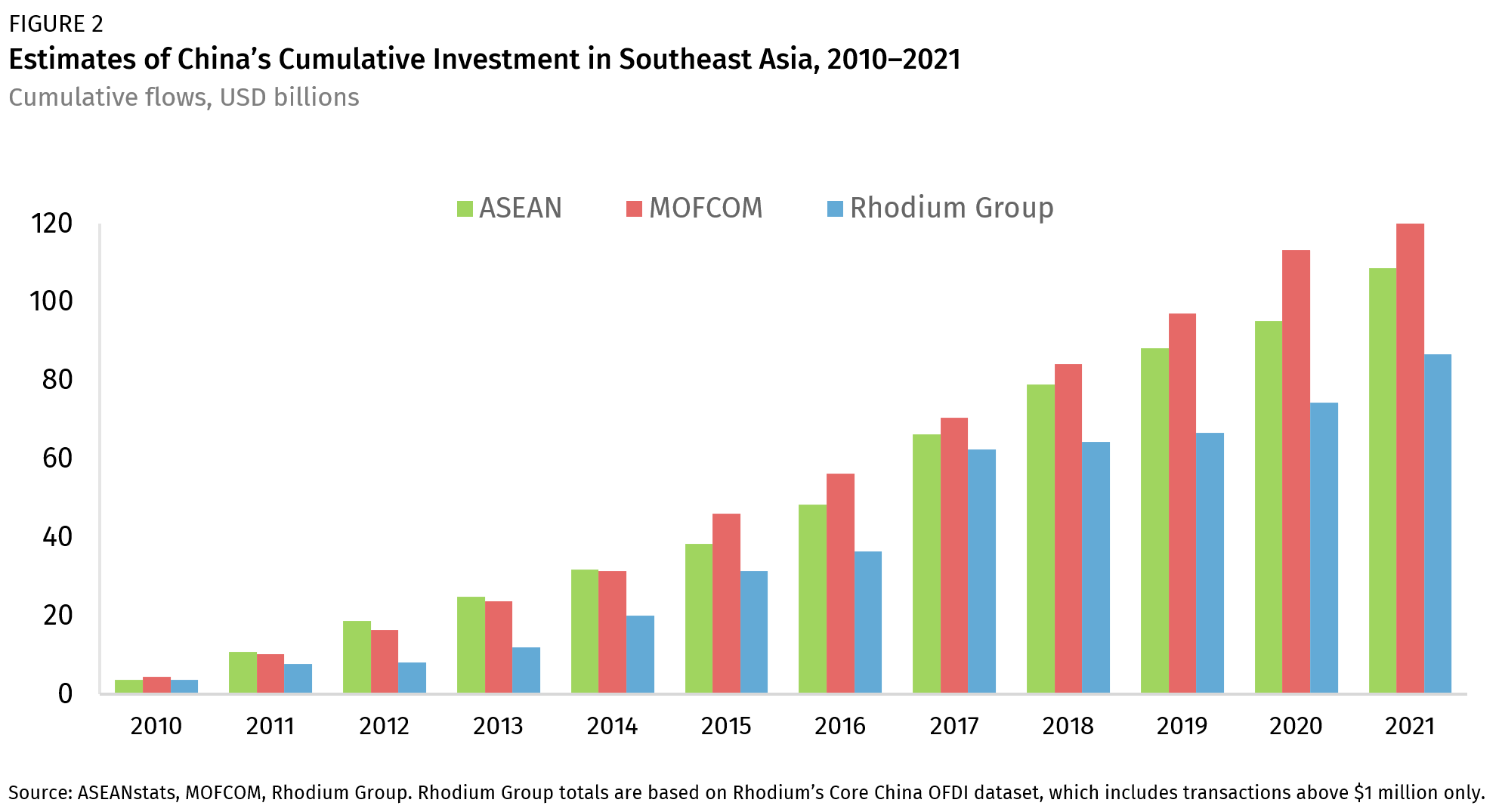

Other regions have seen resilience or even an increase in Chinese investment compared to the 2014–2017 boom period. Southeast Asia is one of these regions with a growing Chinese investment footprint. Various sources agree that Chinese firms’ investments into Southeast Asia have grown rapidly in the past decade, countering the overall trend of falling global investments (Figure 2). According to ASEANstats (the statistics division of the ASEAN Secretariat), annual Chinese FDI in Southeast Asia grew from only $3.6 billion in 2010 to $10 billion by 2016; annual totals were $13.6 billion in 2021. Data from China’s MOFCOM show a similar growth trend, with annual flows of around $4.4 billion in 2010 reaching an average of $14.3 billion per year from 2018 to 2020. China’s overall share of FDI in Southeast Asia also grew from 6 percent in 2010 to an average of 12 percent from 2018 to 2020.

Rhodium’s Core China OFDI dataset on global acquisitions and greenfield FDI projects by Chinese companies follows the overall growth trajectory that official data show, but headline investment is lower than in official statistics and more volatile year to year. In the latest available year, MOFCOM shows a total of $133 billion of Chinese investment in the region (2021), ASEAN statistics show $109 billion (2021), and the cumulative value of Rhodium’s transactions amounts to $100 billion (2021).

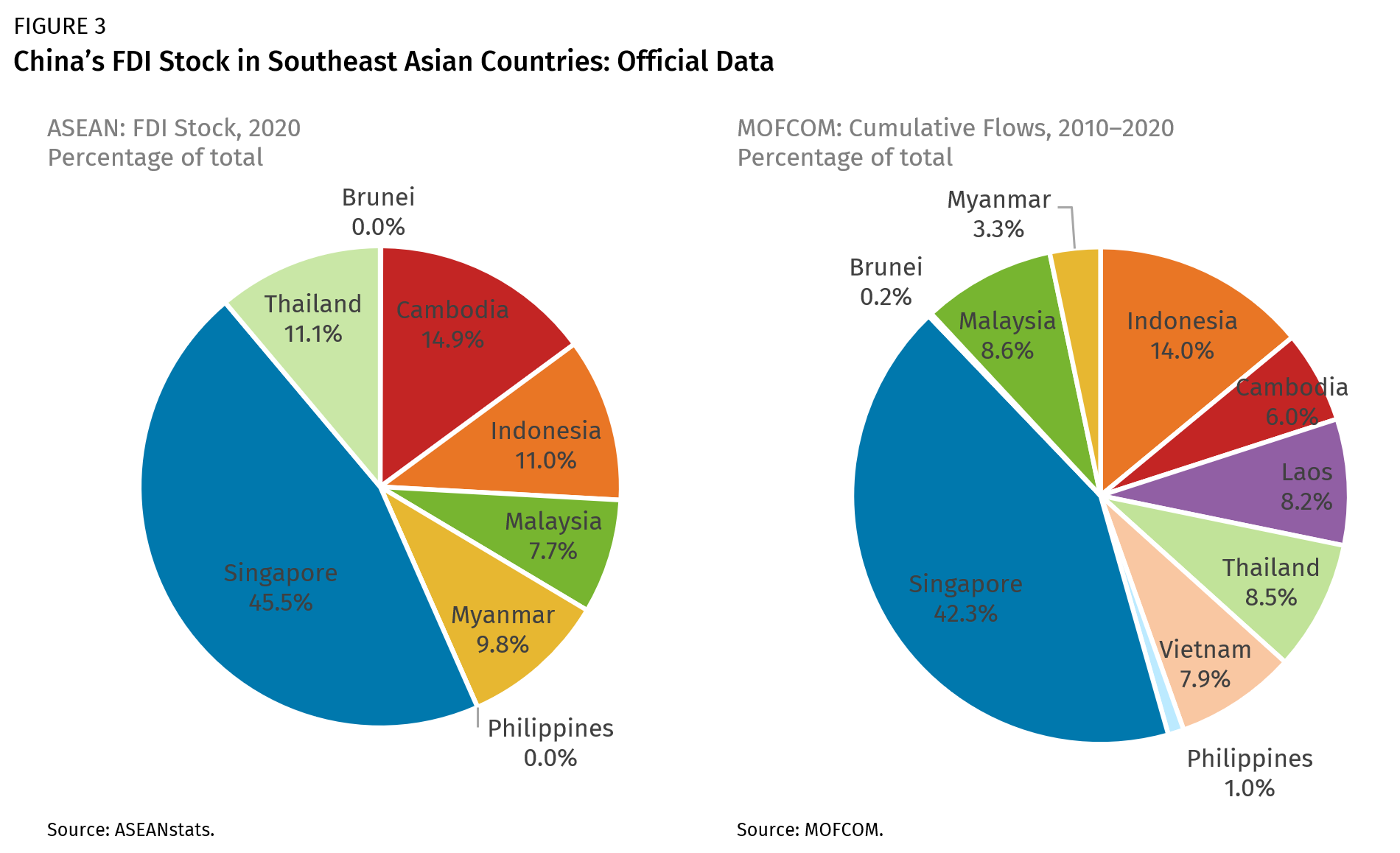

Beyond that aggregate perspective, however, official data vastly disagree on the destinations and target sectors for Chinese investment in Southeast Asia (Figure 3). Singapore is the largest destination for China’s outbound investment in Southeast Asia in both official datasets, but this likely reflects investment routing and roundtripping through a major tax and investment haven. MOFCOM data show that Indonesia is the second-biggest recipient of Chinese direct investment among the 10 countries after Singapore. According to these official statistics, in total, Indonesia received $15.9 billion in cumulative Chinese investment from 2010 to 2020, ahead of Malaysia ($9.8 billion) and Thailand ($9.6 billion). ASEAN data has Cambodia (not including Singapore) as the destination with the most accumulated FDI ($11 billion), followed by Thailand ($8.1 billion) and Indonesia ($8 billion).

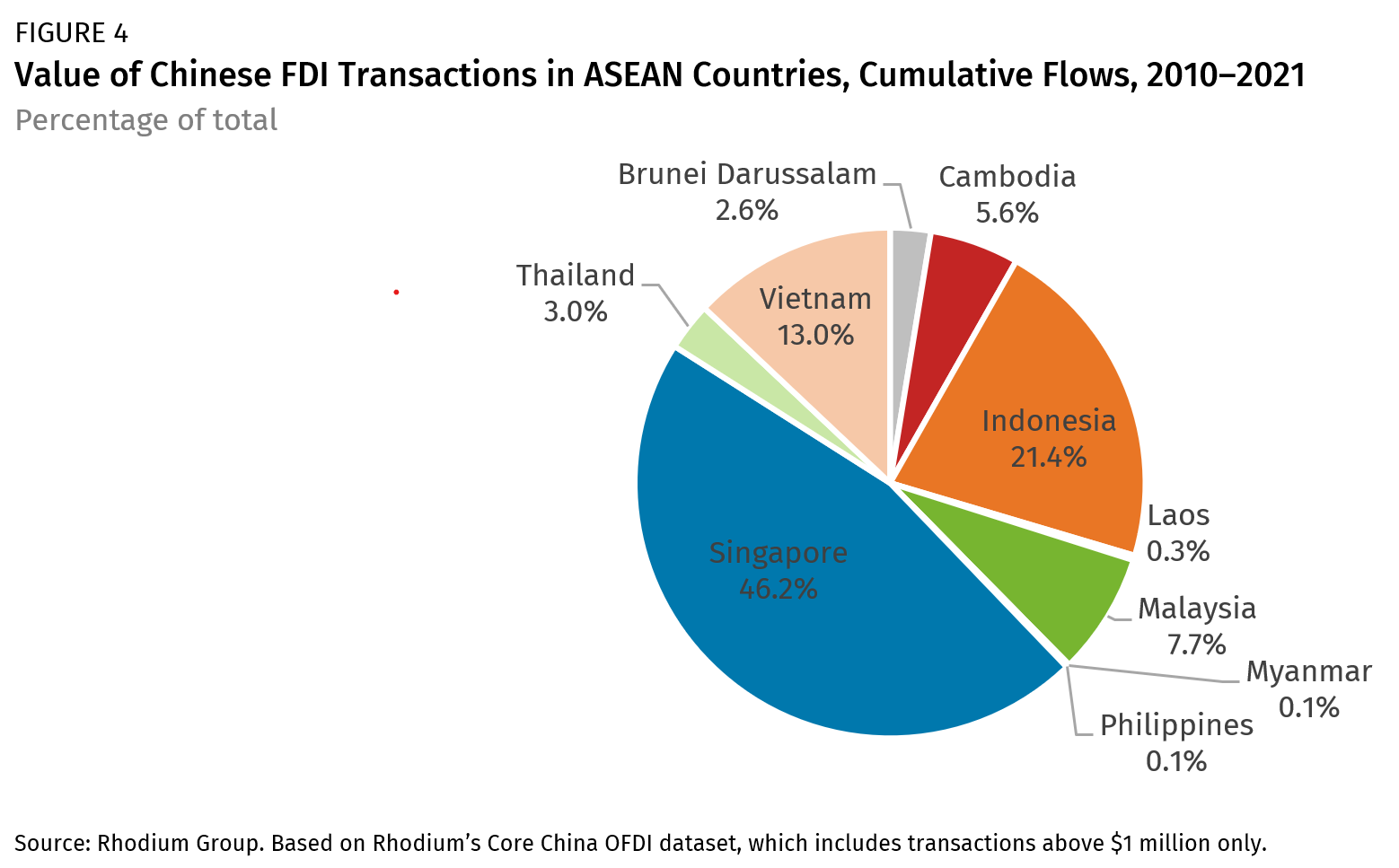

In addition to confusing information about the geographic distribution of Chinese investment, official data also provide very little useful information about the industry distribution of Chinese investment in Southeast Asia. MOFCOM’s aggregate OFDI data are very much distorted toward the industries of the first investment in Hong Kong or other offshore centers (“business services”), and no authoritative breakdown of Chinese investment in Southeast Asian economies by industry is available. Data from host governments widely vary in quality and comprehensiveness. Some governments provide reasonably good data (like Singapore or Malaysia), but other governments do not provide more detailed information, especially for flows coming in through offshore centers (for example, Cambodia or Myanmar). Rhodium’s Core China OFDI transaction dataset provides a detailed perspective on the evolution of Chinese FDI by recipient nation, entry mode, and industry (Figure 4). The Rhodium data confirm that the offshore hub of Singapore is the single largest destination for Chinese OFDI in Southeast Asia. After that, Indonesia has been the biggest attraction for Chinese investors, receiving more than $21 billion in cumulative investment, followed by Vietnam ($13 billion) and Malaysia ($8 billion).

The industry distribution of Chinese FDI transactions in Southeast Asia tracks China’s domestic development and the shifting capabilities of its companies. While Chinese investment in 2010–2015 was chiefly dominated by traditional low-value-added manufacturing sectors and some investments in extractive industries, recent increases in outward FDI to ASEAN countries (especially outside of Singapore) are largely driven by a combination of Chinese private firms exporting their business models and knowhow to new markets and a variety of firms looking to expand their presence in different places on the EV supply chain. The former includes Tencent’s investments in Southeast Asia and Alibaba’s acquisition of Lazada, while the latter is driven by large capital expenditure projects for critical minerals in Indonesia. China’s firms are moving into new technology supply chains in other parts of the world. In Latin America, for example, Chinese investments in key inputs for renewable energy sectors, such as alumina, lithium, and niobium have grown over the past decade.

In terms of entry mode, Chinese FDI in Southeast Asia has historically been dominated by greenfield investment over acquisitions. That pattern generally held up over the past decade, although M&A has become a driving force in certain sectors such as infrastructure and logistics as well as extractive industries.

In the following two sections, we will provide a more detailed description of China’s investment patterns in two Southeast Asian economies—Indonesia and Cambodia—that illustrate how investors’ diverging economic interests can affect local impacts.

Chinese FDI in Indonesia

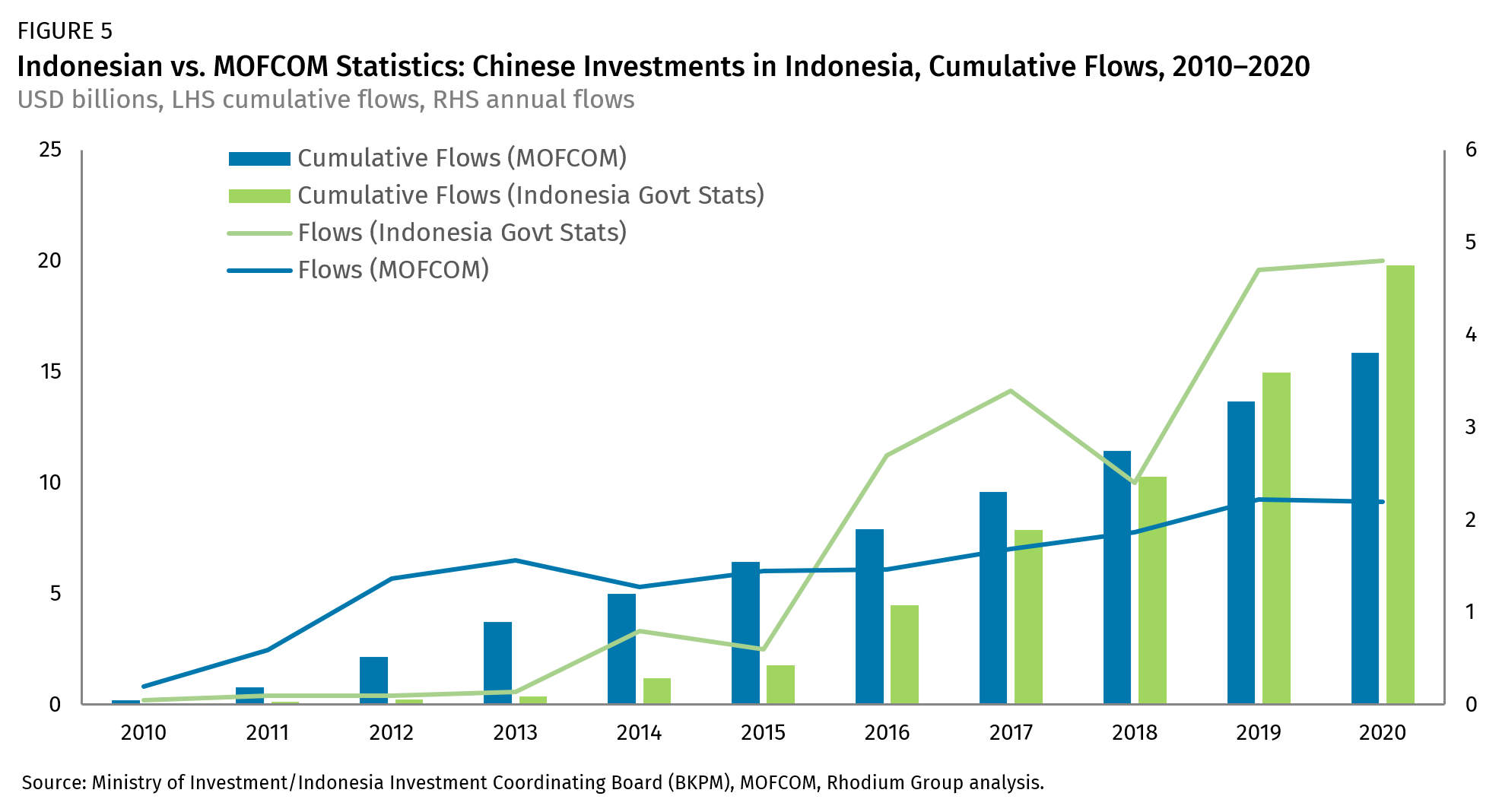

Both Chinese and Indonesian statistics show that China has been a major source of FDI for the Indonesian economy. MOFCOM data captured $16 billion of cumulative Chinese FDI in the country from 2010 to 2020. Indonesian statistics show cumulative flows of $20 billion (Figure 5).

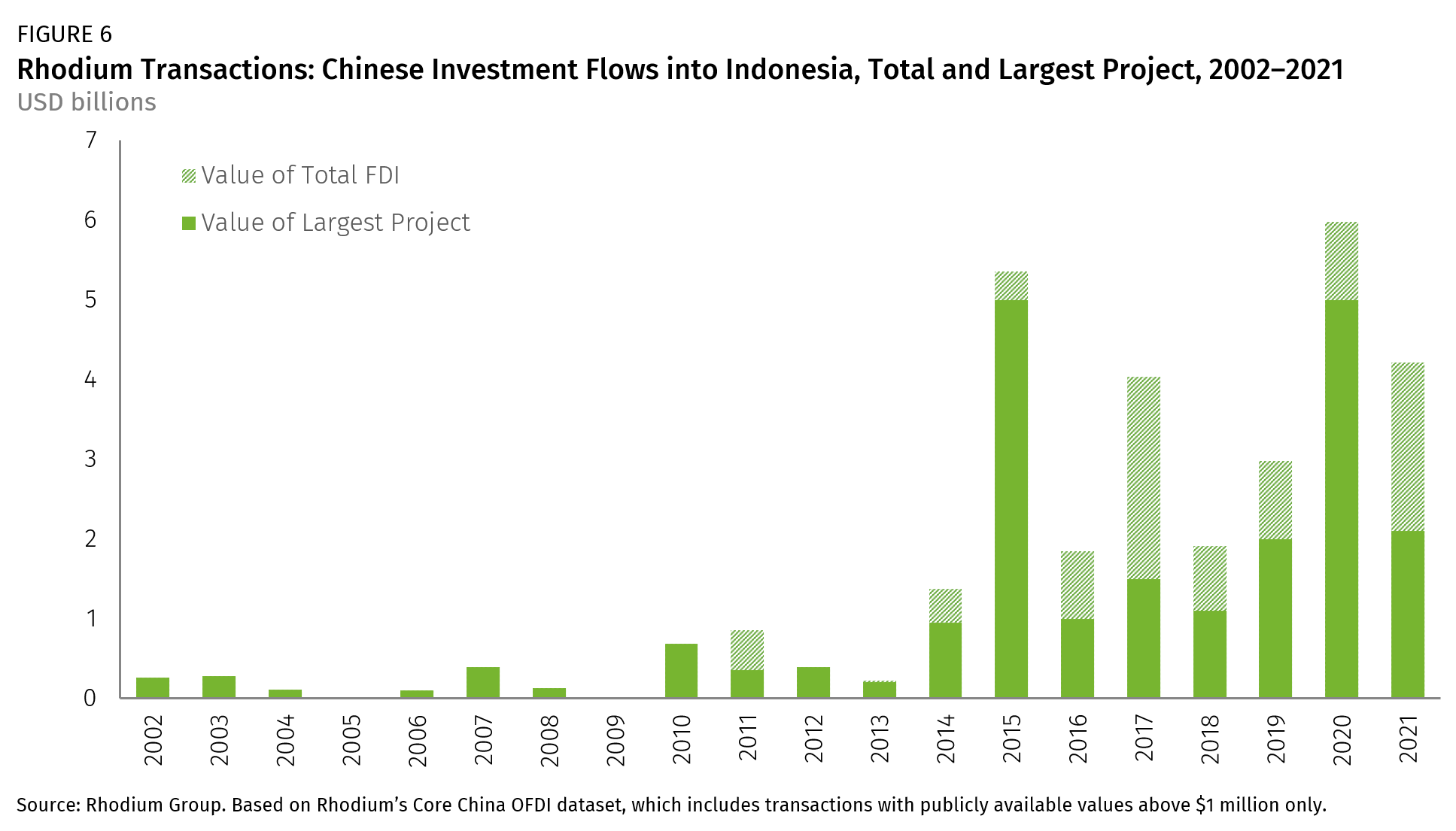

Rhodium’s Core China OFDI dataset includes 110 major transactions with a disclosed value of $22 billion from 2002 to 2021 (Figure 6). More than a third (35) of these were in the financial services sector, despite only accounting for 16 percent of the cumulative value of Chinese investment into Indonesia. By value, the top industries were the basic materials sector (31 percent of value since 2002) and the transportation and infrastructure sector (24 percent). Annual flows spiked in 2015 and momentum remained strong through 2021, with considerable volatility from year to year.

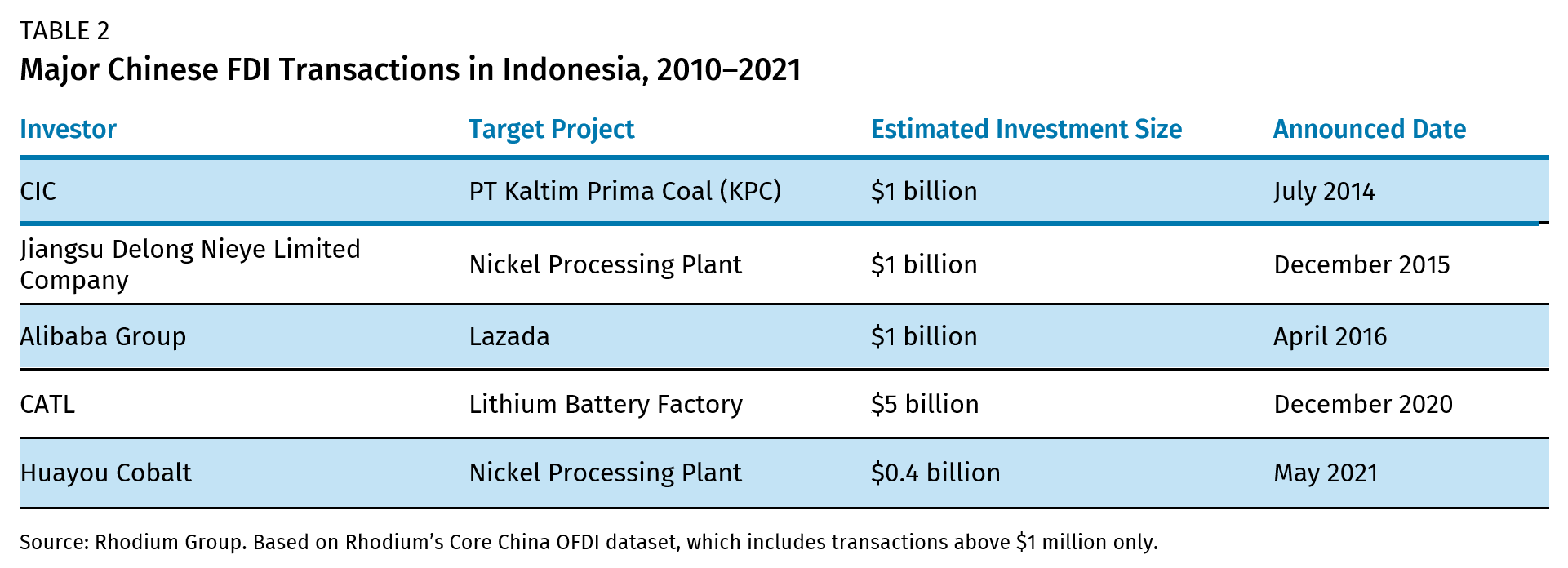

The majority of China’s FDI is concentrated in a handful of large-scale projects. The combined value of the largest project in each year makes up more than two-thirds of total Chinese FDI stock in Indonesia. Of these large projects, the vast majority are in the extractives and infrastructure sectors (Table 2).

The composition of FDI has also shifted in recent years. Prior to 2017, Chinese investment in Indonesia was almost exclusively dominated by controlling stakes. Since then, minority stakes (10–49 percent) by private Chinese companies have become an increasingly important part of China’s overall investment into the country.

The quality of Rhodium Group Core China OFDI data covering Indonesia is generally better than for other countries in Southeast Asia due to better local reporting on financial transactions. However, by only capturing major FDI transactions, our dataset still undercounts China’s actual investment footprint in Indonesia by omitting smaller-scale greenfield investments by Chinese nationals. We also do not capture “hidden” investments in the informal sector of the economy, like small retail or services operations established by Chinese expatriates. In terms of investment value, about 50 percent of transactions in our sample do not have a disclosed value. If we were to estimate the value of these transactions value based on historical patterns in the same industry, it would likely add several billions of dollars to our estimates of cumulative investment.

Chinese FDI in Cambodia

China’s aid and lending relationship with Cambodia is substantial, and analysts estimate China has provided more than $1.8 billion in aid and development finance since 2000. While aid flows and other projects are well-documented, China’s FDI footprint in Cambodia is more difficult to grasp, due in part to data challenges.

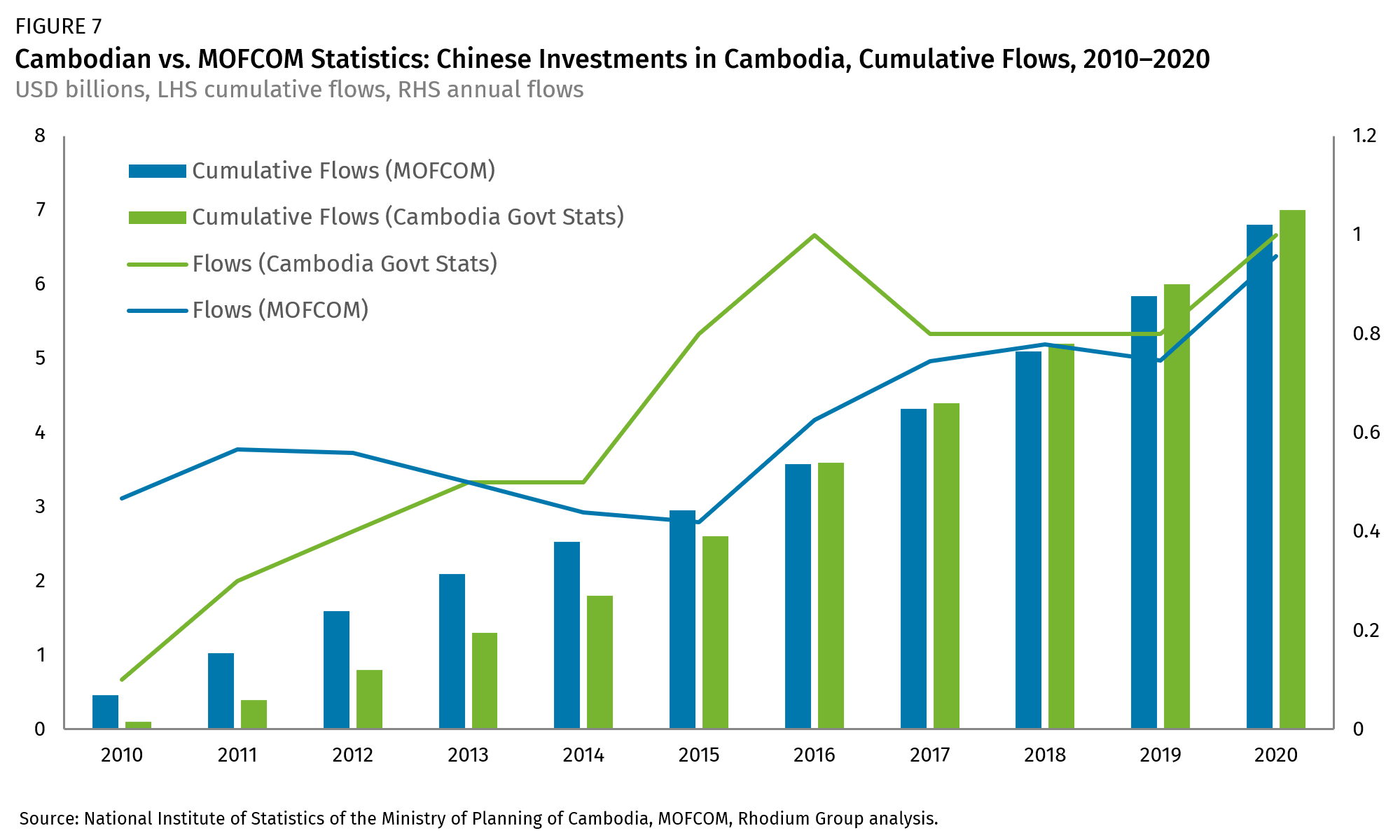

ASEAN statistics show $7 billion of cumulative Chinese investment in Cambodia, which is the third-lowest value in the region only ahead of Myanmar and Brunei. MOFCOM data show slightly less than $7 billion of cumulative Chinese FDI from 2010 to 2020 but do not provide any additional details on the industry distribution or other breakdowns (Figure 8).

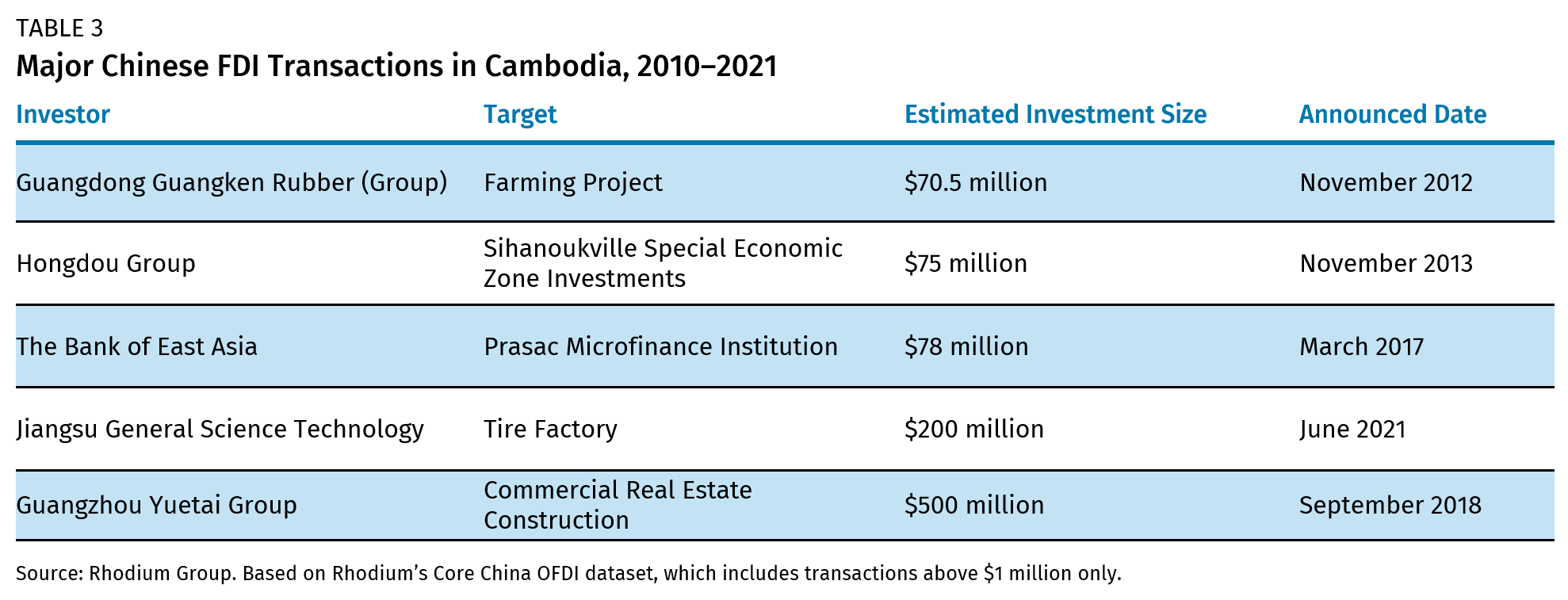

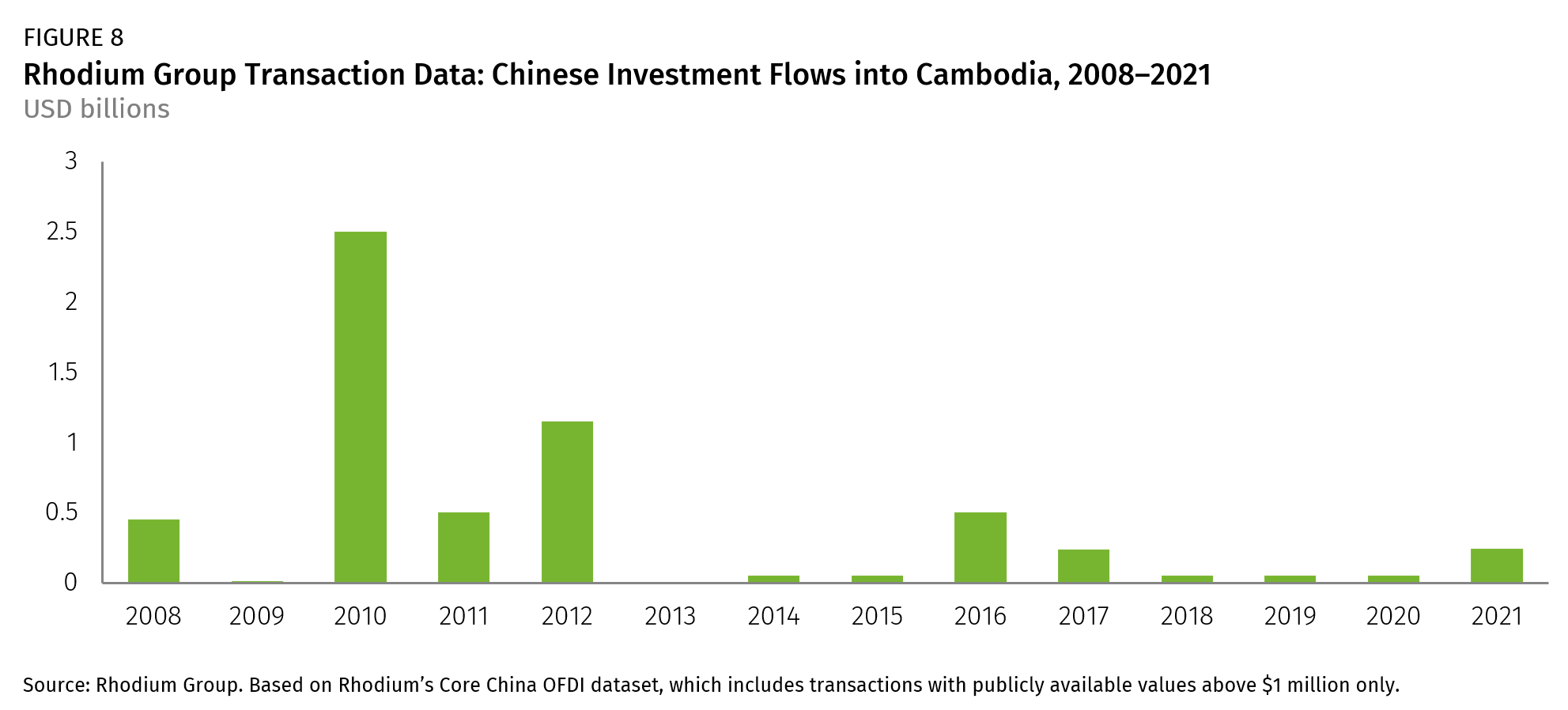

Given the nature of Chinese investment in Cambodia, Rhodium Group’s Core China OFDI dataset only includes 16 transactions from 2008 through 2020 worth about $6 billion (Figure 9). This is certainly an undercount of the true scope of Chinese investment in the country and reflects the shortcomings of the “Core China OFDI” dataset to detect smaller scale transactions and activity in the informal sector of the economy. However, examining specific transactions still offers a sense that Chinese investment is fairly uniformly distributed across a number of sectors, but transport and infrastructure accounts for more than 50 percent of value since 2008.

China’s state-owned enterprises account for more than one-third of the total value of these transactions. Most projects are in the real estate and light manufacturing industries. Compared to Indonesia, we see fewer next-generation investments, including in fintech and other rapidly growing investment spaces. Some of the largest projects are summarized in Table 3.

Cambodia is an even clearer illustration than Indonesia of the importance of expanding alternative data collection to include estimations of informal flows and transactions without public identifiers. Cambodia is in close geographic proximity to China, has a large Sino-Khmer community as well as a significant resident population of Chinese citizens, and has a large informal sector. Combined with historically poor—though improving—statistical reporting by the Cambodian government and civil society institutions (media, think tanks, etc.) that track economic activity, these characteristics mean that many FDI transactions are not readily traceable through public sources.

The ESG Impacts of Chinese Outbound FDI in Southeast Asia

China’s economic engagement with Southeast Asia has helped power regional growth, but analysis also suggests that over the last two decades, China’s economic actors—from firms to banks—have contributed to lasting environmental damage, disrupted local or traditional communities, and promoted corruption in countries around the region. As the nature of China’s outbound investment shifts, ESG concepts are becoming integral to international markets; listed companies in Hong Kong are required to participate in some ESG disclosure, while China has voluntary rules for ESG matters. But ESG is complex, as there is no single global standard for ESG disclosure, and practices that are applicable in one domain may not be applicable to others. We review existing knowledge of the sustainability impacts of China’s global investment before examining the impact of China’s investment on Indonesia and Cambodia to date.

Impacts of China’s Global Investment: Diverse Outcomes

ESG concepts overlap with existing initiatives focusing on the potential impact of investment on environmental, human rights, or political outcomes. As China’s global investment footprint has expanded, the potential for Chinese firms to impact these outcomes has only increased, and existing studies offer a mixed picture of the impacts of Chinese investment. While acknowledging the benefits for recipient countries in the form of development and economic growth, analyses also identify a host of negative impacts on emerging market and developing country recipients of China’s FDI.

Environmental protection is a recurring challenge for projects that receive financing from Chinese institutions, though China’s development projects appear to be gradually improving. Analysis of projects financed by China’s main policy banks—the Export-Import Bank of China and China Development Bank—finds that on average, these projects present a greater threat to biodiversity and environmental protection than projects that receive multilateral funding from the World Bank. However, along with changing patterns of investment and lending in recent years, there has been a decline in the number of Chinese policy bank-financed projects located in environmentally sensitive locations and on indigenous peoples’ lands since 2018. Chinese FDI—especially in extractives or natural resources, agriculture, and infrastructure—has been implicated in environmental degradation and threats to local biomes, including in Africa and Latin America where China’s investment has concentrated in environmentally sensitive sectors. China’s investments in energy are a good example, showing both progress and ongoing challenges. To date, the greatest proportion of China’s energy sector FDI has gone to coal assets, with clear environmental implications. However, this situation is changing, as Boston University data show that financing for fossil fuel power generation peaked in 2015, and investments in renewable energy are taking up an increasing share of China’s outward investment in power generation. FDI has driven much of the growth in renewables. Yet hydropower projects, the largest destination of Chinese investment in renewables, pose their own environmental risks, and other investments in carbon-intensive industries may offset the environmental benefits of China’s increasing support for renewable energy assets.

Similarly, the social impacts of China’s investments—how those investments affect local communities—vary widely. Specifically, questions over Chinese’ firms treatment of local workers and displacement of local labor with workers from China have lingered since at least the early 2000s; China’s investments in specific sectors like mining have featured especially poor safety records. However, in other cases, analysts find China’s enterprises do not present worker health and safety threats, instead contributing to host country worker training and the creation of new local jobs in more productive sectors—like low- and semi-skilled manufacturing (such as assembly line work), construction and real estate, and services. This contrasts theories of labor displacement. Analysts point out that while there is substantial variation in Chinese firms operating abroad, these firms are sometimes subject to special scrutiny due to nationality, and firms that have a neutral impact (or demonstrate good practices) are rarely publicized. At the same time, documented cases of corruption among China’s foreign direct investments pose challenges for recipient governance.

Major differences between Chinese investors at least partly explain these outcomes. Chinese firms operating overseas vary widely in their understanding of local and Chinese law, their capacity to evaluate impact of firm actions on local communities, and their long-term planning and outlook. Research on Chinese investment in Africa, for example, finds that the scope of negative impacts varies widely by company size, sector, ownership, and the host country regulatory environment. Of these characteristics, ownership seems highly important. One study finds that larger and/or state-owned firms are associated with larger, more complex, and environmentally and socially sensitive projects, but also benefit from more robust internal policies, more frequent discussions with Chinese officials, and better capacity to address emerging problems with investments and undertake CSR initiatives. Conversely, private firms making large overseas investments, especially “hot” inflows in sectors like gambling or real estate, may lack clear incentives to work with host countries and mitigate adverse investment effects. However, outcomes can vary widely by company and sector.

A key issue—and one that is seen in the case studies described in this report—is that China’s domestic environmental and social investment policies are generally stricter than policies governing overseas investments and come with explicit enforcement mechanisms. Chinese law has required that foreign enterprises investing overseas only meet the environmental standards of the host country, even if those standards fall below those normally required for Chinese domestic investment projects. Beyond this, there are no binding environmental requirements for Chinese investments abroad, although there are a host of nonbinding and advisory policies promoting “green” investment and environmental responsibility for companies operating overseas. Although China continues to develop new regulations and recent guidelines are beginning to encourage firms to follow international standards in environmental protection, these initiatives remain voluntary.

Existing research directly comparing Chinese firms’ environmental and social impacts to the impacts of firms from other countries is somewhat limited. Focusing on development and infrastructure finance, studies examining China’s BRI suggest Chinese banks have less developed environmental and social oversight systems and regulations compared to multilateral development banks or Japanese and Korean overseas development agencies. Several studies document how China’s overseas projects, including aid projects and those funded by Chinese banks, can have negative ESG impacts. Some work also suggests Chinese foreign direct investors are more active in countries with less developed ESG regimes than investors from other countries and are therefore operating more frequently in contexts with lower preexisting regulatory baselines. Going as far back as the 1990s, for example, research suggests Japanese firms tended to invest in countries with relatively more robust environmental frameworks, as opposed to those with weak environmental regulations. Whether this is due to investor preference for weaker regulation or Chinese firms being “crowded out” of strong investments in countries with more developed regulatory regimes is debated.

However, it is less clear if Chinese foreign direct investors—whether state-owned enterprises (SOEs) or private firms—perform more poorly than investors from other countries in the same sector and host country context, even if the quality of EIAs conducted by Chinese companies overseas are problematic relative to investors from other countries. Here, evidence is limited. Metanalysis by Wang and Zadek (2016) identifies fewer than 10 studies that directly compare Chinese investors to firms from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) or other large developing economies. Much of the existing analysis on labor relations in Chinese investment projects in Africa, for example, focuses on large-scale firms or projects, especially those in construction, textiles, or extractives, as these were the major sectors for foreign investment during the 2000s. Analysis of Chinese work in the mining sector finds that while specific Chinese firms had poor labor relationships and elevated social risks, this was not unique to Chinese firms but instead common across investors in those sectors. Analysis also indicates that Chinese firms differ primarily in their higher number of serious accidents, but otherwise they had similar environmental and social impacts when compared to firms from other countries. More recent work in Kenya suggests that while Chinese firms sometimes displayed poor labor rights policies and practices, US firms were vulnerable to similar criticism.

Impacts of Chinese Investment in Indonesia

In the early 2000s, most of China’s investment activities in Indonesia were in high-emissions sectors like infrastructure, hydropower, and coal mining. Accordingly, China’s impact on Indonesia’s ecosystems has been heavily scrutinized. Supported by BRI, China’s investment portfolio in Indonesia has now expanded and includes manufacturing for the broader Southeast Asian markets, including solar manufacturing, vehicles (including EVs), and other industries. At present, China is attempting to broaden its green energy investment scope in Indonesia by constructing Indonesia’s biggest hydropower plant and setting up an industry for the manufacturing of solar cells.

However, studies suggest the impact of existing Chinese investment on Indonesia’s environment has been mixed. Pramono et al. (2022) recently used remote sensing data to identify risks to biodiversity and local communities from Chinese investment projects, finding that the concentration of investments in sensitive sectors—like coal power, extractives, and infrastructure—has caused vegetation loss and threatened endangered species. Investments from Chinese firms have also presented social risks, including corruption and labor rights issues, which can be compounded by complex relationships between the Chinese diaspora and Indonesians of Chinese descent and other groups and political actors in Indonesia.

On the positive side, some studies suggest China’s FDI has contributed significantly to local economic growth. For example, after the foundation of the Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP), the economic growth of Central Sulawesi Province (where the park is located) increased to over 13 percent annually, much higher than the national average of 5 percent. In addition, while foreign companies tend to invest in high-emissions sectors, research by the OECD Investment Policy Review found that foreign firms, including Chinese ones, are more energy efficient than domestic firms.

The risks of Chinese investment in Indonesia appear set to increase with the passage of the Omnibus Law in 2020, which amended and relaxed over 1,200 articles and regulations—including regulations on environment, forestry, fisheries, investment, and spatial planning—in an effort to streamline and boost FDI. Among the most controversial articles of the Omnibus Law is the repeal of the current regulation requiring at least 30 percent of forest area to be conserved for each watershed area or island. The Omnibus Law also eases the requirements for businesses to carry out an EIA as a precondition to obtaining a business license and limits public consultation to only those who are directly affected by the specific project. Previous major Chinese investment projects in Indonesia, including the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Rail project, have been criticized for poor adherence to Indonesia’s environmental and social impact evaluation regulations.

Case Study: Morowali Industrial Park

Case Study: PT. Sorik Marapi Geothermal (PT. SMGP)/PT. Sokoria Geothermal Indonesia (SGI)

Impacts of Chinese Investment in Cambodia

Investment from China has helped fund needed infrastructure and propelled economic growth in sectors across the Cambodian economy, including textiles and real estate. However, some of China’s investment has come at a substantial cost. Analysts, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), opposition political figures, and others have alleged that some Chinese projects have damaged Cambodia’s environment, promoted corruption, and harmed the interests of Cambodian workers. While proponents often cite the economic benefits of Chinese investment, other analysis argues that the spillover effects of a given project to the wider Cambodian economy may be limited and that large Chinese infrastructure and investment projects in Cambodia provide much in the way of technology and knowledge transfer for Cambodian firms.

Hydropower projects and dams, which have large physical presences that can affect local biodiversity and have implications for local communities that are often forced to resettle, are among the most widely studied types of investment, and researchers have found numerous ESG issues. Other academics have found that non-infrastructure investments in Cambodia, such as manufacturing plants, generally encounter fewer issues. An important finding in the literature is that many of the adverse outcomes of Chinese investment are exacerbated due to lax enforcement on the part of local officials. A study examining Chinese businessmen who engage in bribery, for example, points to the environment of corruption in Cambodia and the need to adhere to local practices to do business. Accordingly, case studies of Chinese projects in Cambodia (including by Cambodian organizations) find noncompliance with environmental and social standards and Cambodian laws and widespread conflicts of interest in both aid and loan projects and investments, including negative impacts in Sihanoukville. One recurring challenge is Chinese firms’ adherence to Cambodia’s environmental and SIA regulations. Limited public access to project reporting documents, such as EIAs and SIAs, exacerbates challenges with compliance monitoring. Cambodian law lacks detailed requirements for the implementation of EIAs and clear designation of responsibility for public disclosure, resulting in a more permissive environment for government actors and firms to sidestep safeguards. In April 2023, Cambodia’s Council of Ministers approved a new Environment and Natural Resources Code. Earlier draft versions of the code dictate more defined responsibilities for government oversight and instate more articulated disclosure requirements. Cambodia’s institutional context is also challenging, government agencies have limited—but improving—capacity to process assessments, consulting firms approved to conduct them vary widely in qualifications, and local elites and politicians can influence how projects are treated.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

Chinese firms’ activities in Southeast Asia are changing, and ESG principles are an increasingly important consideration as they explore new opportunities in Indonesia, Cambodia, and beyond. As our case studies illustrate, how these Chinese firms investing in Southeast Asia implement ESG principles in practice is far from uniform. In some cases, costs to local populations, ecosystems, and governance modes have been significant. The experiences of Indonesia and Cambodia in tracking and managing China’s investments—and their ESG impacts—mirror the larger challenge for countries in the region, as issues of state capacity and enforcement can hamper projects that aim to have a fundamentally positive and sustainable impact, whether in alternative energy, sustainable manufacturing, or other sectors.

Our data and analysis suggest that China’s engagement in the region is fundamentally shifting to new sectors, with a different ESG profile compared to past Chinese investments in the region. Examining four case studies in Indonesia and Cambodia, we see how China’s firms are considering ESG in their overseas operations and responding to global ESG trends.

First, Chinese companies are paying increasing attention to ESG concepts, formulating ESG policies and increasingly disclosing firm-wide ESG activity. However, much of their focus remains on corporate charity and CSR. For recipient countries to know their investment partners, much more is needed, including a comprehensive (and, according to Chinese law, required) system of company-wide disclosure with clear standards and mandatory compliance.

Second, there is no single story of China’s investment in Indonesia and Cambodia, and ESG impacts vary. Some investments are highly opaque, positing clear concerns for corruption and negative social and environmental outcomes, like Dara Sakor. Others overtly embrace “green” and sustainable principles, like the CART Tire plant in Qilu SEZ. The confounding effects of Chinese (and international) industrial zones make it even more difficult to distinguish positive or negative ESG contributions from individual firms, raising the stakes for policymakers and regulators to ensure zones are well planned, well managed, and well supervised to ensure positive ESG outcomes.

Third, host country context in Indonesia and Cambodia matters for ESG outcomes. China’s legal regime for foreign investors, which places most of the ESG regulatory burden on host countries, means that local conditions and practices are important for understanding ESG outcomes. Even where Chinese firms aim (or claim to aim) for higher standards or better compliance, as long as Indonesian and Cambodian regulations lag behind international or Chinese standards, companies will have fewer incentives to perform beyond baseline.

Fourth, transparency remains a recurring issue for the firms in our case study. This implicates the Chinese firms covered in our case studies as well as Indonesia and Cambodia’s transparency and disclosure regimes, which appear to contain major gaps. For example, without ready access to impact assessments, it is very difficult to determine how effectively firms understand and address (or fail to address) ESG risk.

Fifth, in terms of environmental sustainability, across countries and industries, our case studies observe recurring challenges, including questions regarding the protection of waterways, marine areas, and protected land. The investments in our case studies are all located near sensitive zones that do not appear to have received sufficient consideration and, in some cases, appear to have developed in contravention of Indonesian or Cambodian law or best practices. In the case of Dara Sakor, the legal status of protected land did not serve as an effective safeguard to prevent the development of protected areas.

Sixth, the green future comes with costs and risks to countries that will play key roles in global supply chains. The battery materials and geothermal power station explored in this report exhibit poor environmental performance in one or more areas, including water safety and pollution controls, even as the technologies they advance become increasingly important for wider environmental outcomes.

Our research has several implications for policymakers and the philanthropic community.

First, increasing the transparency of China’s overseas investment patterns and investors remains a key challenge even in this next phase of Chinese overseas investment. Tracking and confirming Chinese outbound investment projects remains challenging, and tightened capital controls and greater national security scrutiny have further increased existing transparency problems. These issues are particularly acute in Southeast Asia because of governance problems, large informal sectors, and other factors. Understanding the ultimate ownership of Chinese overseas investments is also critical for identifying the ESG risks a proposed investment may pose for potential partners, national and local authorities, and civil society groups. Creating tools to improve the capacity for data collection and due diligence among local stakeholders should be a primary goal for philanthropies and international organizations. Importantly, transparency in China’s overseas investments is deteriorating, not improving.

Second, improving corporate-level ESG disclosure and reporting is another important pillar for more robust ESG impact assessment in both China and potential partner countries, even at an aggregate level. The reporting available from our sample Chinese firms does not include quantifiable metrics, even on the company’s aggregate impact. Specific ESG standards and frameworks like the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) standards and the Global Reporting Initiative are a starting point but have not been uniformly adopted, even by firms that report ESG. Adopting specific ESG criteria allows ESG impact to be distinguished from traditional CSR, offering a more detailed insight into company impact. Beijing’s appetite for greater foreign portfolio investment and offshore fundraising offers a window of opportunity to work with major institutional investors and impactful ESG funds to accelerate that process and create positive spillovers for other Chinese companies. Chinese firms’ attempts to build global consumer-facing brands provide greater incentive for ESG compliance.

Third, improving country capacity to review and monitor project-level environmental and social impact assessments and conduct ongoing reporting is important to ensuring better outcomes in Indonesia, Cambodia, and beyond. Our research confirms findings of previous studies: in Cambodia and Indonesia, responsibility for reviewing and enforcing regulations may be spread across different agencies or levels of government that lack sufficient staffing or expertise to handle complex ESG issues. Importantly, improving recipient institutional capacity improves officials’ ability to deal effectively with investor firms from all countries, not just China, and attract investment from other destinations.

Fourth, engaging communities affected by an investment early, often, and meaningfully is difficult but critical. Even where consultations are nominally held, they may be held too late, may lack sufficient community participation, or may be unable to affect project design or outcomes, even following project-related accidents or negative outcomes. Traditional CSR initiatives involving donations or agricultural training do not offset these needs. Chinese firms’ reliance on joint ventures, local partners, or secondary consultants for impact assessment and engagement may compound these risks.

Fifth, it is important to tread carefully with large land concessions, SEZs, and industrial zones. These are particularly complex to supervise and manage from an ESG perspective. It can be difficult to distinguish how individual firms adhere to ESG principles. On the other hand, shared zones offer opportunities for shared infrastructure and collaboration on ESG outcomes.

Sixth, these changes in China’s engagement with Southeast Asia and regional supply chains offer an opportunity for Indonesia, Cambodia, and outside investors to share best practices and improve ESG outcomes. Cambodia’s draft overhaul of environmental laws is an encouraging start, and China continues to roll out new voluntary guidelines and standards that can serve as a blueprint—if not a binding guide—for its overseas firms. New activity in next-generation sectors presents a chance to improve ESG outcomes at all levels, but it will require a concerted effort—from regulators, investors, and other groups—to achieve consistently strong ESG outcomes in foreign investment.