Now for the Hard Part: China’s Growth in 2023 and Beyond

Even under best-case COVID-19 exit scenarios, China faces strong economic headwinds which will subdue growth in 2023 and beyond.

Since reform and opening began in 1978, China has had the benefit of catch-up growth on its side. The country was coming from such a low base, and its vast market had so much potential, that its leaders did not have to do much, besides get out of the way, to deliver impressive growth. Cyclical slowdowns, even severe ones, were always followed by a return to rapid expansion. Will the end of China’s zero-COVID policies produce the same result in 2023? Some economists believe so, predicting a robust recovery in the world’s second-largest economy, driven by pent-up household demand. Foreign governments and multinational corporations must decide whether to believe the optimists. In this note, we consider China’s economic outlook and conclude that even the best COVID endgame is unlikely to deliver a rosy 2023. While GDP growth above 4.5% may seem reachable at first glance, the more one looks at the assumptions needed to achieve that level of expansion, the less realistic it seems. We believe that growth as low as 0.5% is within the realm of the possible. If Beijing starts crucial, long-deferred structural reforms in earnest, growth between 1-3%, in 2023 and over the medium-term, would be a reasonable expectation.

2022 in Review

Many analysts assumed Beijing would deliver its stated GDP growth target of “around 5.5%” in 2022. Few imagined that the downturn in the property sector would place a hard ceiling on expansion. Even fewer thought that China would continue to insist on draconian COVID lockdowns at a time when the rest of the world was opening up, in part thanks to mRNA vaccines. But by June 2022 the reality had begun to sink in, and officials gave up on 5.5%. Premier Li Keqiang, according to reports at the time, urged local bureaucracts to rush out pro-growth measures to prevent a second-quarter economic contraction. The growth target set just three months before was already out of reach.

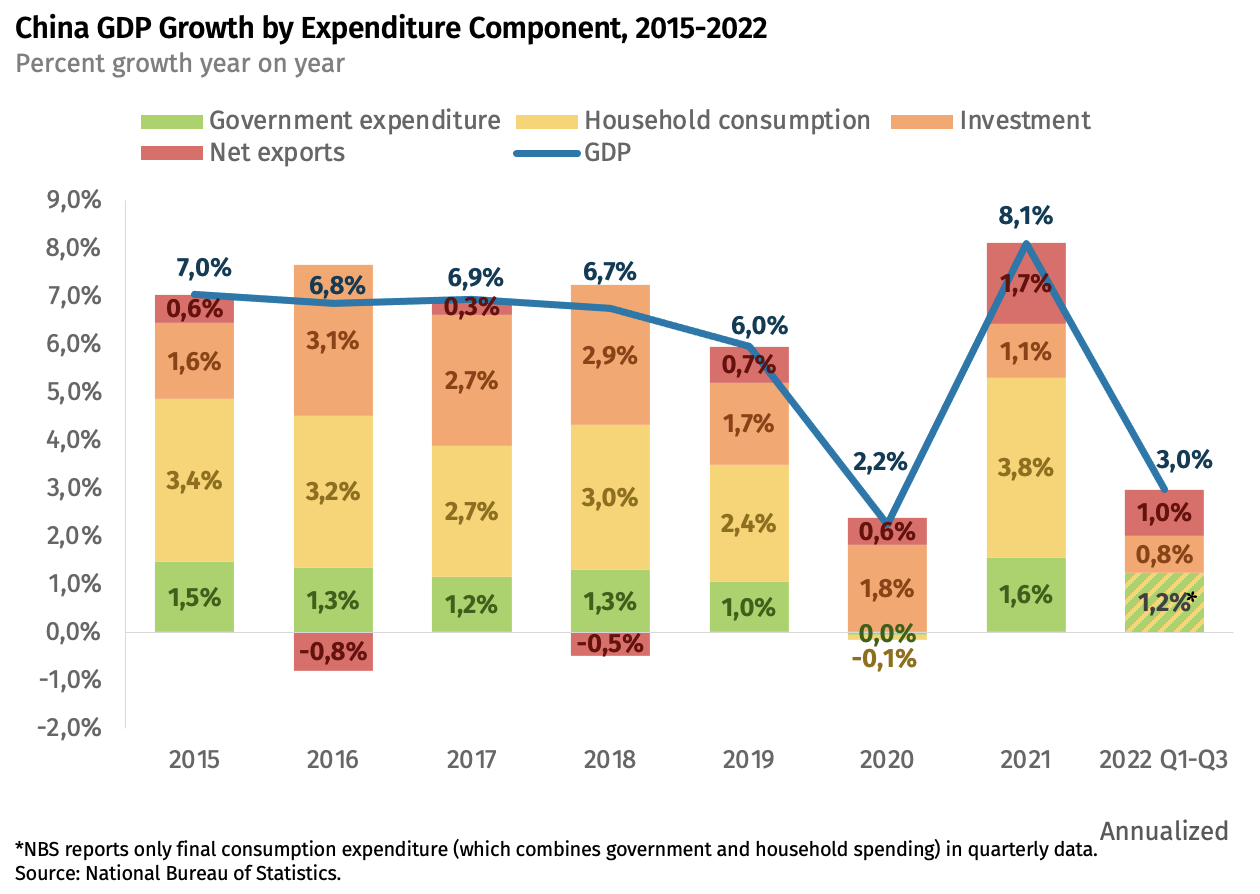

Preliminary GDP data for 2022 will not be released until late-January, but for the first three quarters, growth was reported to average 3% on an annualized basis, supported by modest increases in household and government consumption (+1.2%), business investment (+0.8%), and net exports (+1.0%). Some questioned whether this was an accurate reflection of the actual performance of the economy, but for the sake of discussion we will accept the 3% growth story through the first nine months of the year.

Should we assume that the final quarter of 2022 came out better? No, given the serious worsening of economic conditions as the year ended. The zero-COVID lockdowns were extended through October (to ensure stability for the 20th Communist Party Congress) and November, before they were abandoned abruptly without much in the way of additional policy guidance in December, following the outbreak of protests over the lockdowns. This means weaker fourth quarter and full-year performance than we saw in the first three quarters. In terms of household consumption, retail sales fell 0.5% in October and again by 5.9% in November. Government spending is difficult to proxy but there is little reason to expect it to offset depressed household activity. If we conservatively assume a 2% contraction in fourth-quarter consumption, similar to what we saw in Q2, we could expect a full-year GDP contribution from households and the government of around 0.8 percentage points.

The lockdowns at the start of Q4, and the rampant spread of COVID thereafter, impaired business investment activity. New property starts plunged by a record 49.7% in November, and completions fell 18.3%. Industrial output fell for construction-related products, including cement (-3% y/y), asphalt (-7%), and UPR, a chemical used in roofing and piping in real estate construction (-39%). Given these indications, China will be lucky to report another 0.6 percentage points of GDP growth from investment for the full year 2022.

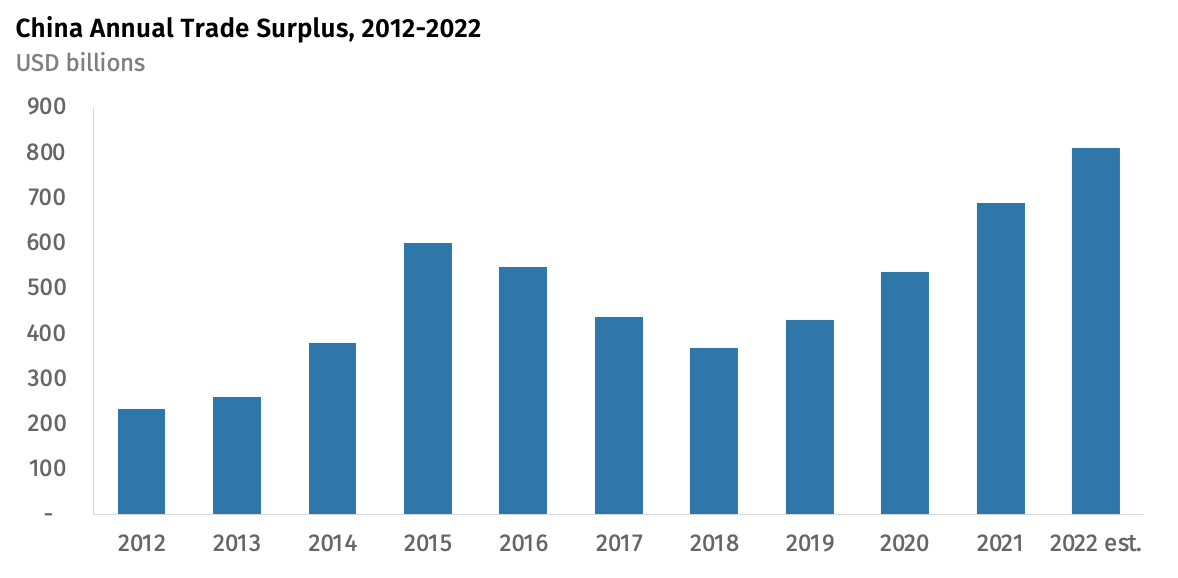

China’s net exports (exports minus imports, the external component of GDP by expenditure), rose to an all-time high in 2022, above what was already an epic level in 2021. This surprised many analysts, who assumed there was nowhere to go but down. But by late in the year, with a global recession in the air because of rising global interest rates and inflation, the trend for China’s net exports finally turned. At best, there may have been a modest increase in the fourth quarter, resulting in a maximum contribution of net exports to 2022 GDP of 1.1 percentage points. However, it is just as likely that exports have been overstated this year by 10-15%, as companies inflated them in order to claim export tax rebates.

Put together, the official data and our observations of fourth quarter performance suggest full-year 2022 GDP growth of about 2.5%, with numerous reasons to suspect that the real performance was even weaker. In Q1, Beijing’s statisticians reported accelerating growth from the prior quarter, despite a deepening property sector slowdown and lockdowns in numerous cities. The property sector continued to decline throughout the year, with completed floor space down nearly 20% in the first eleven months of 2022 compared to the same period last year, and new starts down nearly 40%. Yet Beijing continued to report growth in fixed asset investment of over 5%—roughly the same pace of growth as in 2018, long before the slowdown in the property sector took hold. Given China’s preoccupation with delivering strong results, we expect official 2022 growth to come in as high as 3%. In reality, the economy is likely to have grown by less than 2%, and possibly not grown at all.

2023 Outlook

With a 2022 baseline to work from, we can look ahead to 2023. While the zero-COVID millstone around the neck of the Chinese economy will be cast off over the course of the year, the sudden, chaotic way in which pandemic policies have been changed means that growth will be hampered in new ways. Importantly, the economic headwinds that are unrelated to COVID are likely to persist or even worsen. We look at each in turn.

Investment

Diminishing property sector investment will continue to be the main structural drag on growth in 2023. New construction starts, which presage the volume of real estate activity to come, fell by 44%, 36% and 50% in September, October, and November, respectively. The property sector downturn is hard-wired into the first half of 2023.

Yet even after the 2022 downturn, property is still running too hot for underlying real demand. We estimate a sustainable level of demand—a level consistent with buying houses to live in, rather than for speculation—at 550-750 million square meters annually. China’s annualized housing sales are still at 1.24 billion square meters after peaking at 1.73 billion in June 2021. To reach sustainable levels, construction will need to continue contracting at the current rate for four to six more quarters.

Infrastructure investment is likely to be a drag as well. Local governments are under fiscal pressure due to declining revenue from land sales. Local government financing vehicles—LGFVs, the primary mechanisms for implementing infrastructure projects—are in the midst of a credit crunch, and are likely to see defaults in 2023. Policies have been geared toward reducing the number of low-return investment projects, though rules were loosened somewhat in April 2022. Policy bank lending has been used to close the worst gaps, but these spigots cannot match last year’s 1.4 trillion yuan in quasi-fiscal lending. Put together, these constraints mean that infrastructure will probably be a modest drag on growth in 2023, rather than a positive.

Finally, it is hard to imagine private sector investment—in new factory lines or retail spaces, for instance—driving growth given the current COVID-19 chaos and ongoing confusion about the state’s attitude toward market forces. Private firms often take their cues from foreign consumers rather than Beijing. The IMF expects global trade growth to fall from 5.5% in 2022 to 3.8% at best in 2023, or as low as 1.2% in a global recession scenario. Under these conditions, China’s export-oriented manufacturers will be wary about investing in new capital stock and facilities.

In typical pre-COVID years, investment would contribute between 2 and 4 percentage points a year to China’s headline GDP growth. Given the headwinds buffeting the investment climate in 2023, China would do well to match or slightly exceed last year’s pace, wringing out ¼ to 1 percentage point of additional investment growth, at best. A deeper property contraction, local government financing vehicles defaults, or a bigger hit from a slowing global economy could easily lead to weaker investment, or a drag on GDP growth of 0.5 to 1 percentage point.

Net exports

Exports were an important growth driver for China during the pandemic. In pre-pandemic years the contribution of net exports to GDP generally ranged between -1 to +1 percentage point, but net exports contributed 1.7 percentage points to growth in 2021, propelling the nation to reported growth of 8.1% in that year. With China enjoying a record trade surplus, net exports will probably account for one-third of 2022 growth.

But in 2023, we can expect external demand to be weaker. In addition to weaker global conditions, policy confusion at home is likely to hamper export performance. Manufacturers had developed “closed-loop” systems to keep employees isolated from the virus. Now, in a rush to get past lockdowns, there are reports of employees with COVID being told to come to work. In a chaotic environment of high infections and worker absenteeism, it is realistic to expect production to be hampered for a substantial part of 2023.

For net exports to contribute to 2023 growth, an already historic surplus would have to expand further despite these conditions. In theory this may be possible, but we consider it unlikely. Perhaps if China’s terms of trade shifted heavily in its favor—with import prices for oil and other commodities falling and export prices holding up—an additional 0.5 percentage point GDP contribution from net exports might be possible. However, it is more likely that China’s export growth continues to slow and net exports act as a drag on growth of about 0.5 percentage points.

Consumption

In GDP accounting, total consumption demand is made up of two sub-components: household and government spending. The biggest wildcard for overall growth in 2023 is household spending. Households were heavily constrained in 2022 due to lockdowns and travel restrictions, and hopes for a consumption rebound in 2023 hinge on a surge of pent-up demand being unleashed in response to the zero-COVID exit.

But there are several reasons to be cautious about a surge in consumer demand in 2023. Households are putting money into savings at record levels, particularly in time deposits with 3 to 5-year maturities that are expensive to redeem in the short term. Unemployment rates among workers aged 16 to 24 reached nearly 20% earlier this year and are still high at 17%. The global slowdown is likely to affect employment in China’s export-oriented manufacturing sector. China’s property sector slowdown will continue to hurt job prospects in construction and related sectors, affecting employment and income. The government is trying to stabilize expectations about property values, but housing prices in the less-regulated secondary market are already falling in Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities. Falling home values typically weigh on the propensity to consume, because a substantial share of household wealth is tied up in real estate.

A rebound in consumer spending in 2023 would require a successful rollout of consumer stimulus measures, but Beijing has few tools at its disposal to achieve that. Individual income taxes are already very low, at around 1% of GDP. Tax breaks on autos and subsidies for rural purchases of durable goods are already in place. One possibility is consumption coupons, though prior programs have been limited in scale. More widespread deployment of coupons would require both new programs taking advantage of ubiquitous digital payment platforms like WeChat and a major paradigm shift away from supply-side-focused stimulus.

Household consumption growth approaching pre-pandemic trends would mean a 2 percentage point contribution to 2023 GDP growth. An outcome between 2022 levels and pre-pandemic trends would be closer to a 1 percentage point contribution.

Government spending is constrained by the same fiscal headwinds that are undermining infrastructure investment: weak local government revenues from taxes, fees and land sales. A return to pre-pandemic “normal” would mean a 1 percentage point contribution to 2023 GDP growth from government spending, while a continuation of the constrained government spending growth seen in 2022 would result in a 0.5 point contribution at best. As 2022 comes to an end, government budget deficits are hitting record highs. In that environment, more debt is not a prudent solution. But local government obligations have nowhere to go but up, as they are forced to assume “quasi-fiscal” debts run up by nominally private, but in reality state-directed, LGFVs.

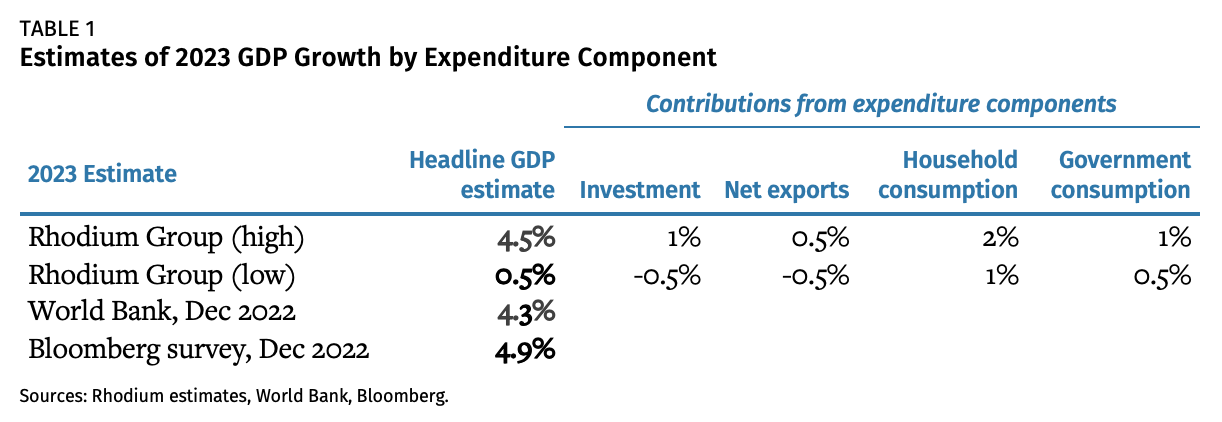

We have presented a high and low range for each of these four components (Table 1). If everything—including factors (like exports) that are not under Beijing’s influence—moves in the right direction for China, GDP growth could reach 4.5% in the coming year (though this would probably mean pushing the real estate correction further into the future, resulting in higher deferred costs). This is close to the latest World Bank forecast for China’s growth, and a little below the median forecast of economists in a recent Bloomberg survey. In other words, many organizations are predicting growth levels that, in our view, only make sense if everything goes right for China. The low end of our range shows the Chinese economy barely expanding in 2023 (0.5%).

The Age of Slow Growth

China’s highly restrictive COVID policies played an important role in its weak economic performance in 2022, and the end of these policies should provide a boost once disruptions associated with the rampant spread of the virus begin to ease. But zero-COVID was just one of many brakes on growth, and the others will not vanish with a wave of Beijing’s policy wand.

Demographics are a persistent, long-term drag. The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reported population growth of only 480,000 people (+0.03%) in 2021, meaning China’s demographic peak has arrived. The working age population has been declining for several years, with fewer young people entering the workforce and more people retiring. Moreover, there are serious concerns about the educational preparedness of tens of millions of young, rural Chinese who are entering a 21st century economy.

After a decade of credit-fueled growth, China’s financial system has reached its limits. Banks are saddled with a decade of unrecognized non-performing loans that must be rolled-over year after year. As that pool has grown, banks have had to employ an ever larger share of new credit to keep the engine going at the same speed. Unable to grow its way out of these liabilities, China must gird for a wave of new financial risks, which will test the credibility of the country’s technocrats.

Productivity growth should be a driver of economic expansion at the middle-income stage in which China finds itself. But the wellsprings of productivity are not flowing as they used to. The economic reform agenda has stalled or shifted into reverse in some areas. Beijing continues to push expensive industrial policy programs with little to show for them in terms of productivity or self-reliance. Private sector and foreign firms are increasingly wary of regulatory directions and ideological signals.

As China’s leaders consistently point out, external conditions are becoming more challenging as well. Geopolitical headwinds are constraining China’s access to foreign capital, markets, technology, and talent. Permissive access to foreign consumers has allowed China to achieve economies of scale and scope in the past. This is changing, especially in important sunrise sectors. Rather than add to China’s growth, the external dimension may increasingly act as a drag.

Finally, China faces formidable challenges related to climate change. While the green transition will affect all developed and developing economies, China’s reliance on heavy, carbon-intensive industries make its burden heavier than most.

Given the stack of structural constraints that China faces, adjusting expectations for 2023 and beyond is necessary. Lower expectations are critical to re-establishing credibility and justifying painful, but necessary policies to shore up China’s economic potential. Slower growth is the new normal for this decade. Lower but sustainable growth in the 3% range per year would still amount to $600 billion in additional output annually, when set against the $20 trillion base that China will have established in a few years. That best case long-term growth rate is substantial and it is achievable. While it requires sacrifices and concessions to the need for political and market reforms in the near-term, it would mean less sacrifice down the road. The reform work involved is not new to Xi Jinping or the Party, nor is a tough period of adjustment. Acknowledging lower growth potential in 2023 would be a signal that China is ready to get started today.