Tapped Out

The current weakness of localities’ finances is the primary reason that there has been no meaningful fiscal support for China’s recovery this year.

The 2022 annual results of 2,892 local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) reveal a rare decline in overall cash positions, relative to rising interest costs and debt levels. The current weakness of localities’ finances prevents Beijing from utilizing fiscal policy to support the economy. In fact, this is the primary reason that there has been no meaningful fiscal support for China’s recovery this year.

Recent public calls for help from Guiyang and Hohhot reflect widespread local government financing distress. These pleas should multiply in short order, increasing pressure on Beijing to promptly address the mounting debt crisis before it becomes irreversible. The critical question after a probable large-scale local debt restructuring is what role local investment will continue to play in the future of China’s economy.

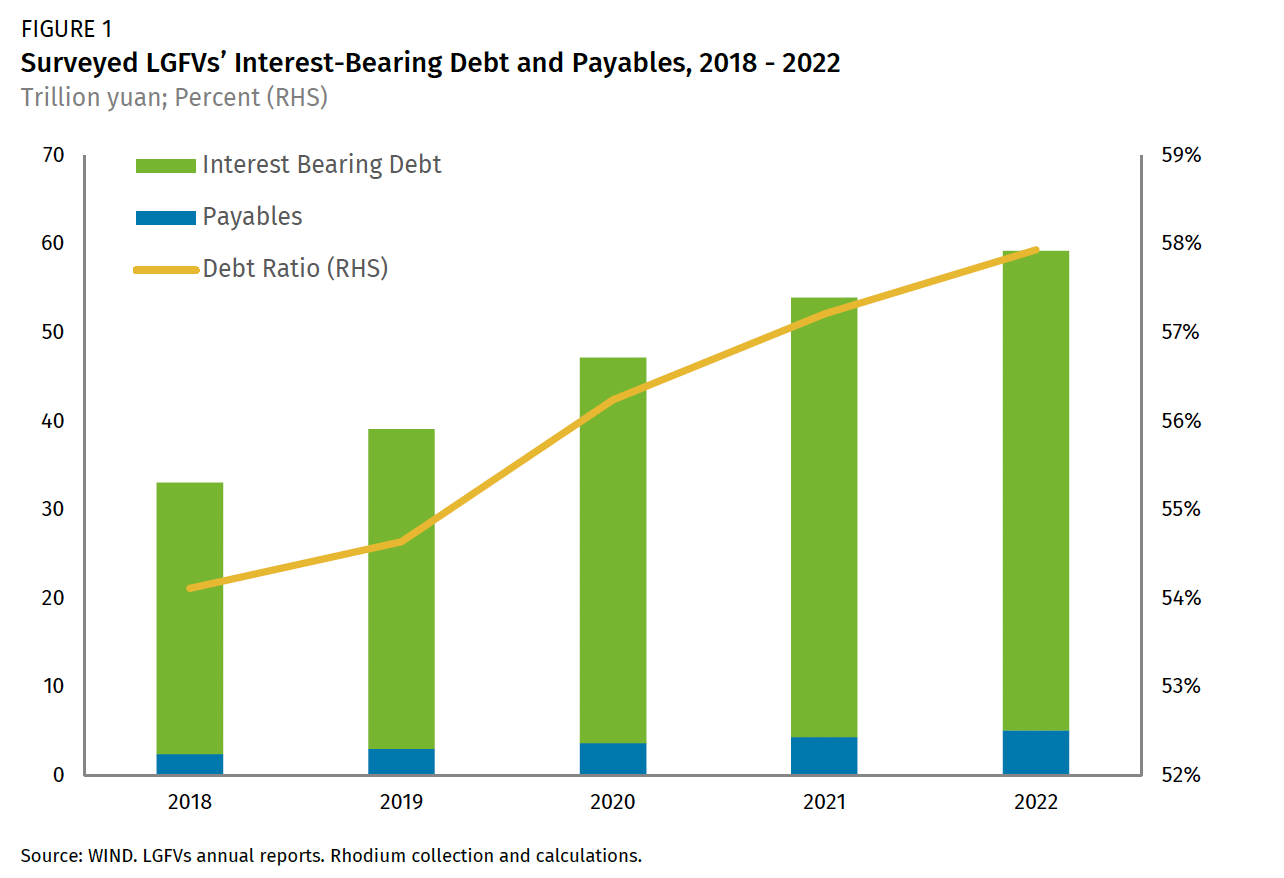

We have been consistently warning about the risks of local government debt over the last three to four years. We have flagged the possibility of defaults on LGFV bonds as an amplifier of the debt crisis, which would require an immediate response from Beijing. The nature of the debt problem is well understood at this point. LGFVs alone hold over 59 trillion yuan in interest-paying debt and payables, around 50 percent of GDP. Other explicit and implicit local debts through schools, hospitals, and other institutions may bring the total closer to 100 percent of GDP. But the scope and implications of the local debt crisis are much wider and larger than conventional wisdom suggests.

Discussions of the problems of LGFVs are over a decade old, precisely because LGFVs have played such an important role in China’s growth model throughout the past decade. Restructuring local debt or “solving” the local government debt problem would change China’s entire economy. Any meaningful resolution of the local debt problem would likely trigger a significant structural slowdown in investment, and a sharp slowdown in economic growth for the next decade.

Public calls for Beijing’s assistance from the governments of Guiyang, the capital of Guizhou province, and Hohhot, the capital of Inner Mongolia, mark the beginning of the end of local governments’ rapid debt accumulation. Guiyang’s government claimed in a summary of work in 2022 that default could occur at any time, while Hohhot’s government cited heavy debt burdens and interest costs, claiming they had limited capacity to manage their debts. These are explicit cries for help from China’s localities, and they will likely be followed by others as the political costs of breaking the silence about debt weaken. At this point, China cannot allow local government investment to collapse, but similarly cannot finance this investment using current methods.

Picking the Bad Apples

LGFVs can negotiate debt extensions, or bully contractors and suppliers by defaulting on acceptances. But they cannot escape the annual interest payments on their existing debts. In February we measured localities’ coverage of interest payments with a broad measure of fiscal revenues, which we would argue is the most reliable barometer of financial risks within LGFVs (See Feb 16, “Running Out of Buyers in China’s Corporate Debt Market”). The top three cities on our list were Lanzhou, Guiyang and Liuzhou, which all experienced credit events in recent months. An LGFV in Kunming (the sixth on our list) was the most recent to report a technical default last Friday after failing to pay investors on a maturing bond, and then a separate LGFV in Kunming reported another technical default on Monday.

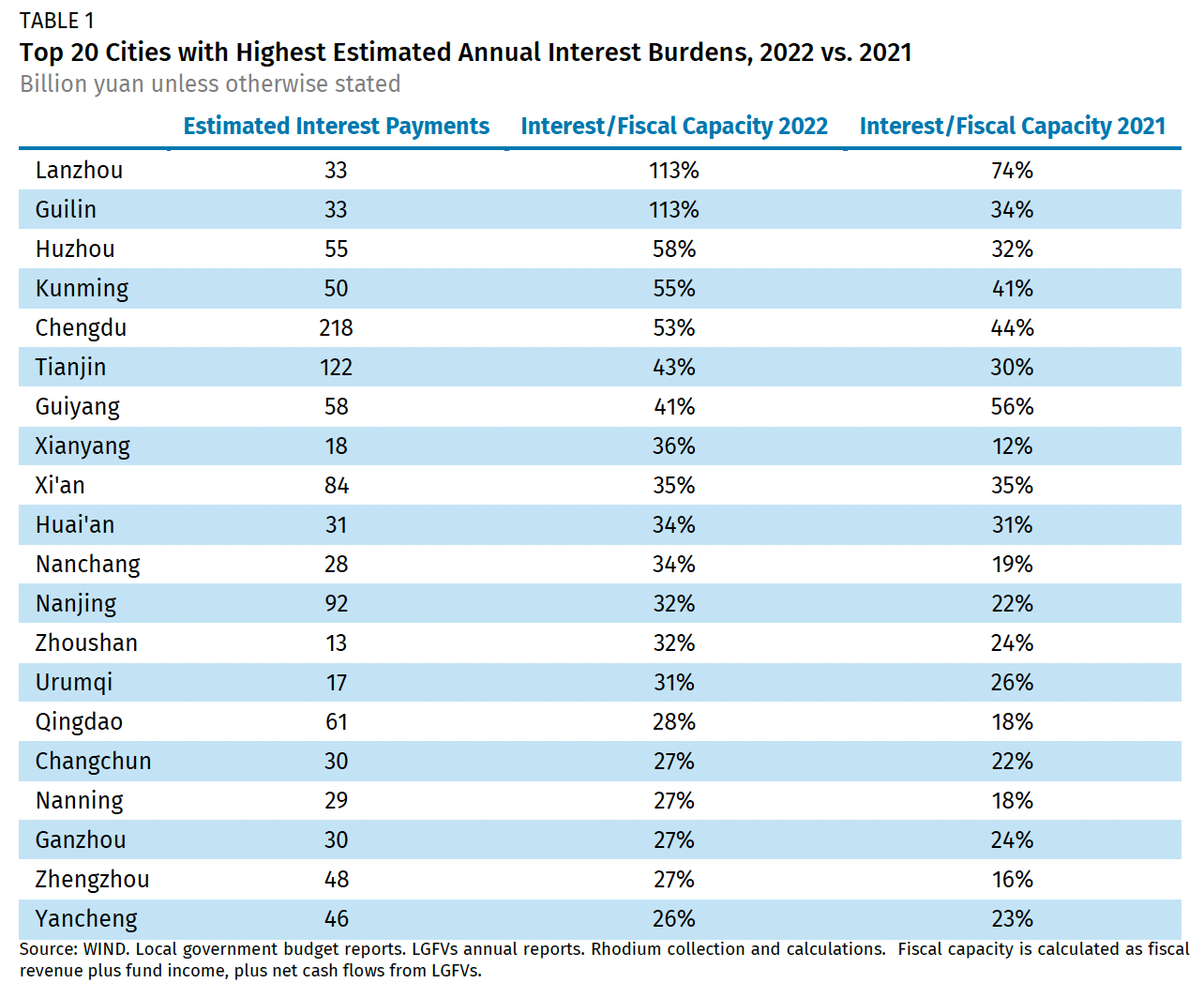

We surveyed the 2022 financial results of 2,892 LGFVs, as most of these reports are only released in late April. Using these results, we can update the table to see the latest city-level measures of financial vulnerability. The top 20 cities facing financial stress did not vary considerably from our previous list, but all of them are now facing worse conditions than last year, except for Guiyang (Table 1). In aggregate, given 205 cities with available financial data in 2022, half were making interest payments accounting for 10% or more of their fiscal resources (fiscal revenues, fund income, and net cashflows from LGFVs), a threshold we believe suggests difficulty in managing debt servicing costs. That ratio was one-third of all cities in our February survey of 318 cities using 2021 annual data. The other cities who have not yet reported results in 2022 are likely to end up as rotten apples, given that delays in publication typically suggest bad news is being withheld temporarily.

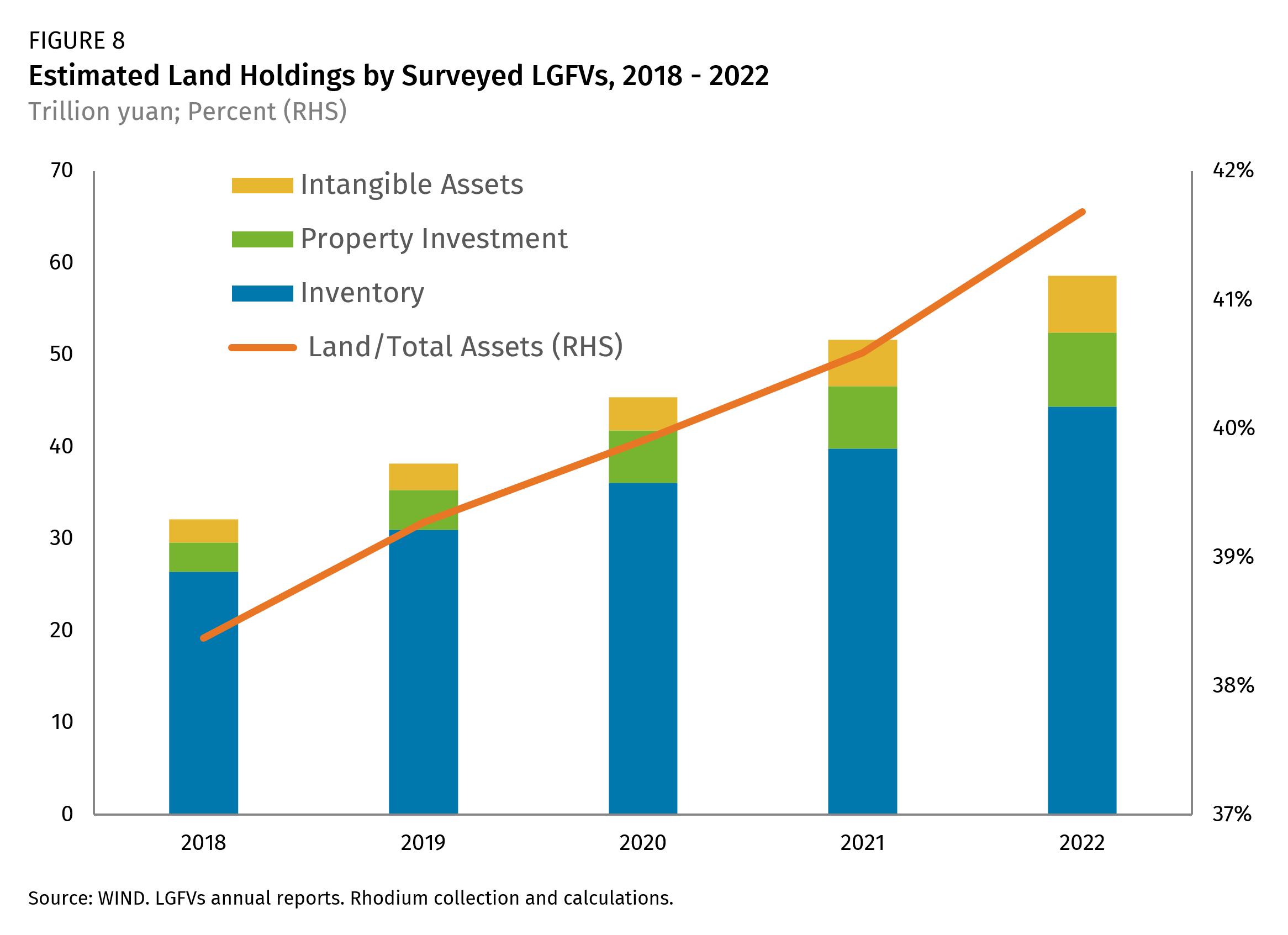

The sharp deterioration in these cities’ interest coverage is mainly a result of shrinking income. Official fiscal revenues took a significant hit last year because of tax exemption measures, while cash flows of LGFVs worsened sharply. Our survey of LGFVs’ 2022 annual reports revealed a 10.3% decline in their cash positions to 7.8 trillion yuan by the end of last year, the first such drop since 2018. Although LGFVs managed to improve financing cash flows in the second half of 2022, their spending also increased significantly, particularly due to their involvement in the land market. The growth of LGFVs’ inventories, which is a proxy for their land holdings, accelerated to 11.4% last year after four consecutive years of a slowdown.

In addition to declining cash positions, LGFVs’ total interest-bearing debt reached 54 trillion yuan by the end of 2022, with an additional 5 trillion yuan in payables to contractors and suppliers (Figure 1). Total interest payments rose to 2.9 trillion yuan last year, despite a marginal decline in overall funding costs. The rising proportion of short-term borrowing, accounting for 25.7% of total interest-bearing debt compared to 21% in 2018, has intensified refinancing pressure. President Xi has urged changes in the maturity structure of local debt and lower interest burdens. Although borrowing costs have declined, the pace has not been fast enough to alleviate interest burdens, and the maturity structure is changing in the opposite direction to Xi’s declared intentions.

Only around one-fifth of our surveyed LGFVs have sufficient cash on hand to honor their short-term debt obligations and cover interest payments. Some of these loans will of course be rolled over this year, but addressing the local debt problem is now an urgent task for Beijing (See Apr 7, “The Urgency of Restructuring Local Debt”).

The central government has recently appointed Li Yunze, a veteran in the financial industry from China Construction Bank and, more importantly, an official with extensive experience in local affairs, to lead the newly established Financial Regulatory Administration (FRA). The leadership of the two new financial commissions under the Chinese Communist Party, which will oversee the country’s financial work and replace the FSDC (Financial Stability and Development Committee), has yet to be finalized. It would not be surprising to see officials with local experience leading key positions there to better address the local debt problem.

Given the establishment of a comprehensive new financial regulatory framework in the first half of this year, the long-awaited quinquennial National Financial Work Conference will likely be held sometime during the summer. It is highly probable that the main theme of the conference will revolve around developing plans to address local debt problems, with further details expected in the second half and implementation scheduled for later this year and early 2024.

Carrying a Heavier Backpack up a Steeper Hill

Deleveraging efforts resulted in a slowdown in LGFV debt growth in 2018. However, the COVID outbreak prompted Beijing to revert to fiscal stimulus during the pandemic years. As a result, interest-bearing debt incurred by LGFVs surged by 21% in 2020 and an additional 14% in 2021. While policies towards local debt growth have fluctuated in the short term, the overall trajectory still aims to control debt in the long term. Even with policy bank financing assisting in funding local investment in late 2022, growth of LGFVs’ total interest-bearing debt slowed sharply to just 9.1% last year. The total balance of debt held by our surveyed LGFVs rose to 54 trillion yuan from 50 trillion yuan at the end of 2021.

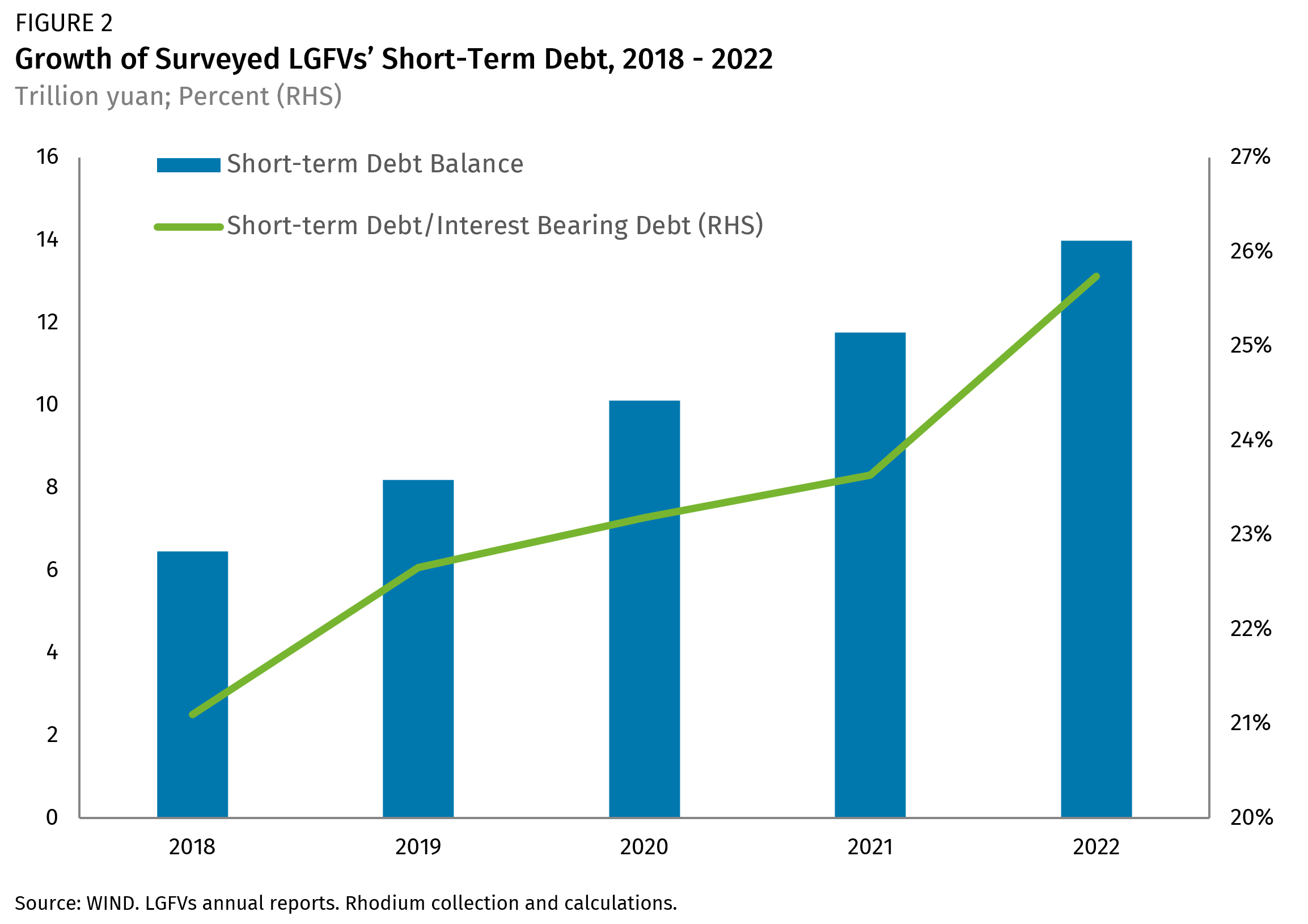

Against a slower growth of debt, one concerning development is the rise in the proportion of short-term debt, which reached 25.7% last year, the sharpest increase since at least 2018 (Figure 2).

LGFVs’ current financial conditions resemble those faced by property developers in 2017 and 2018. Even investors who believe in Beijing’s financial commitment to LGFVs do not expect those implicit guarantees to last forever, because of the size of the debt burden. Eventually, LGFVs may default. Consequently, investors are reluctant to assume duration risk and prefer to avoid long-term bonds issued by LGFVs to the extent possible. When property developers saw the same market conditions, they sold more bonds with put options embedded, providing investors with the flexibility to exit the bonds earlier. However, many of these puttable bonds were among the first to default in recent years. In today’s market, investors often opt for short-term LGFV bonds with maturities of less than one year, particularly in the openly traded bond market. The increase in short-term debt adds to LGFVs’ refinancing pressure as they have to continually roll over these debts.

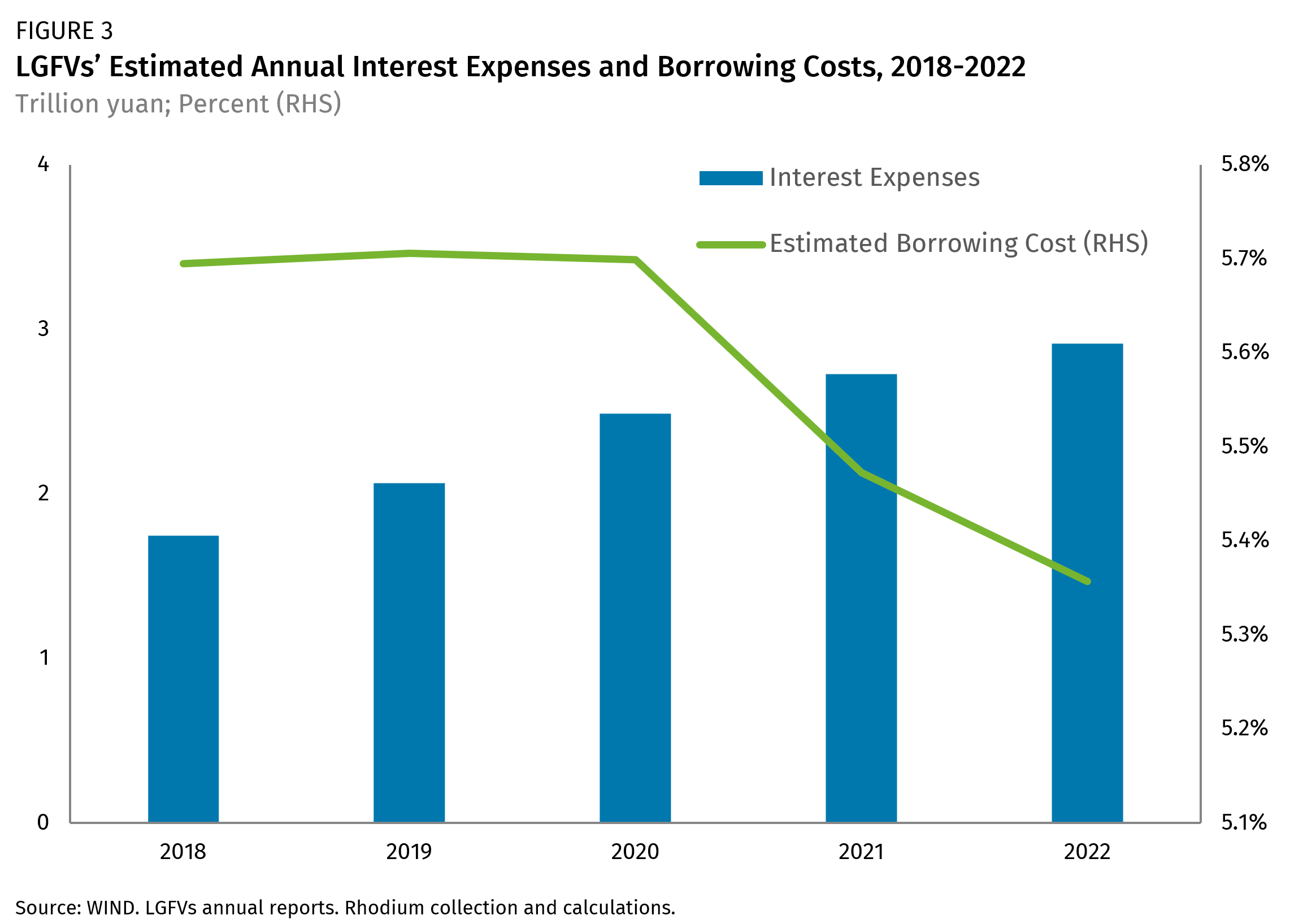

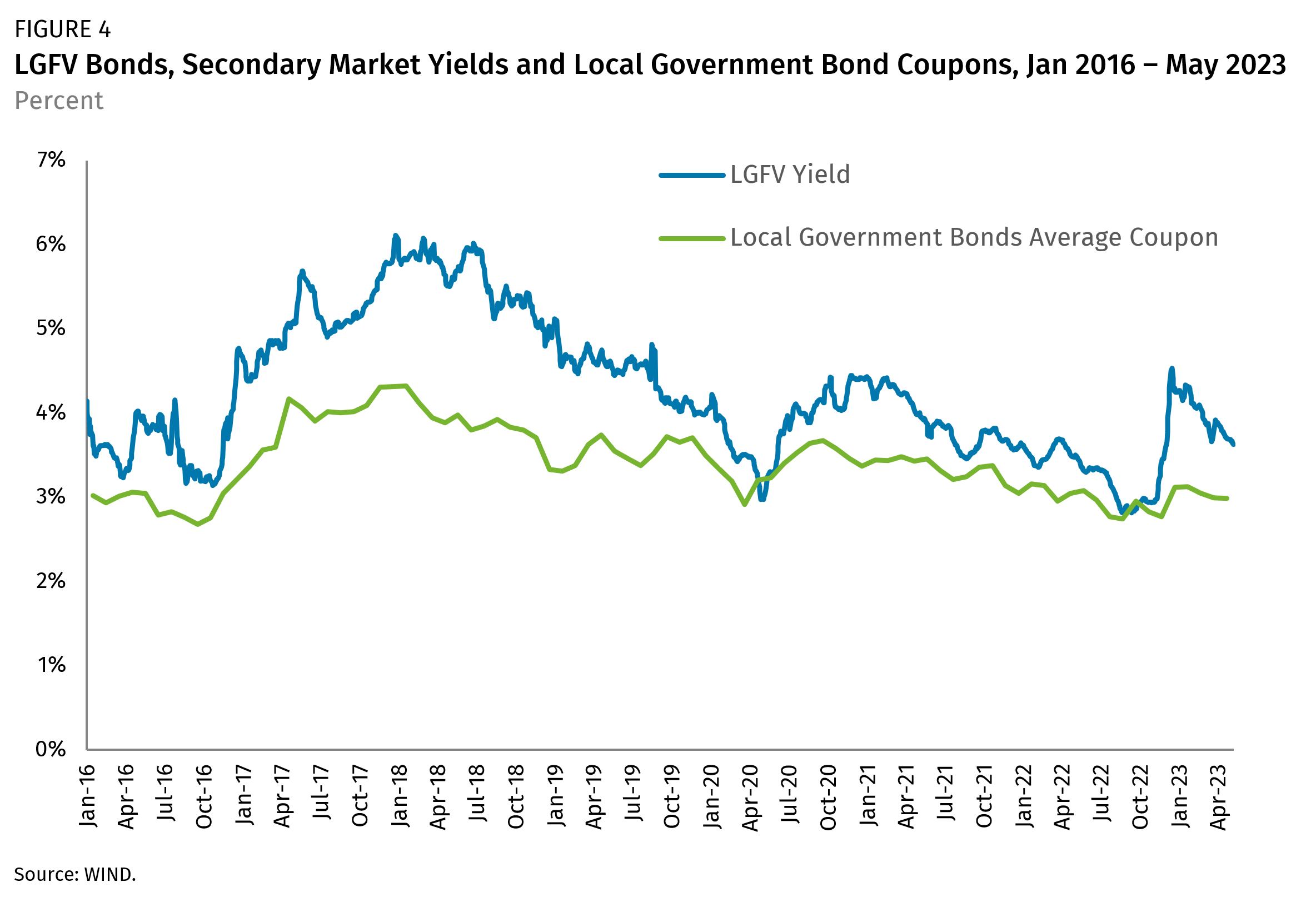

One advantage of a rising proportion of short-term borrowing is that it is cheaper. LGFVs’ estimated borrowing costs fell for the third consecutive year to 5.36% in 2022, but they remain higher than the average corporate lending interest rate of 4.12%. The higher costs can be attributed to borrowing from shadow or informal banks. Additionally, monetary easing by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has helped to reduce LGFVs’ borrowing costs in the bond market, including official local government bonds and LGFV bonds.

Despite the decline in interest rates, total interest expenses still increased in 2022 along with the rise in overall debt levels. LGFVs paid 2.9 trillion yuan in interest on their debt last year, up from 2.7 trillion yuan in 2021 (Figure 3). It is likely that these numbers underestimate the real interest expenses, given LGFVs’ widespread recapitalization of interest expenses, where there are few details revealed within LGFV financial disclosures.

In its Q1 monetary policy report last week, the PBOC reiterated Governor Yi Gang’s golden rule on appropriate interest rate levels, stating that rates should be slightly lower than growth (r below g). Rates that are too low may encourage speculation, while rates that are too high may make debt unsustainable. While we agree with the PBOC’s application of this rule, the sustainability of LGFV debt requires far lower interest rates than overall economic growth. Most LGFV spending and investment aims to provide affordable public services rather than generate significant financial profits. LGFVs only have a median return on assets (ROA) of 1% in 2022, a ratio that is not only declining but well below the median ROA of 4.6% for A-share listed firms last year.

This is a key reason why we anticipate Chinese interest rates must gradually decline over the long term, in order to make local debt burdens sustainable. Monetary policy will need to be set based on the weakest elements of China’s financial system, particularly localities and their LGFVs, rather than the stronger sectors of the economy.

Rising Spending and Investment Obligations Deplete LGFVs’ Cash Positions

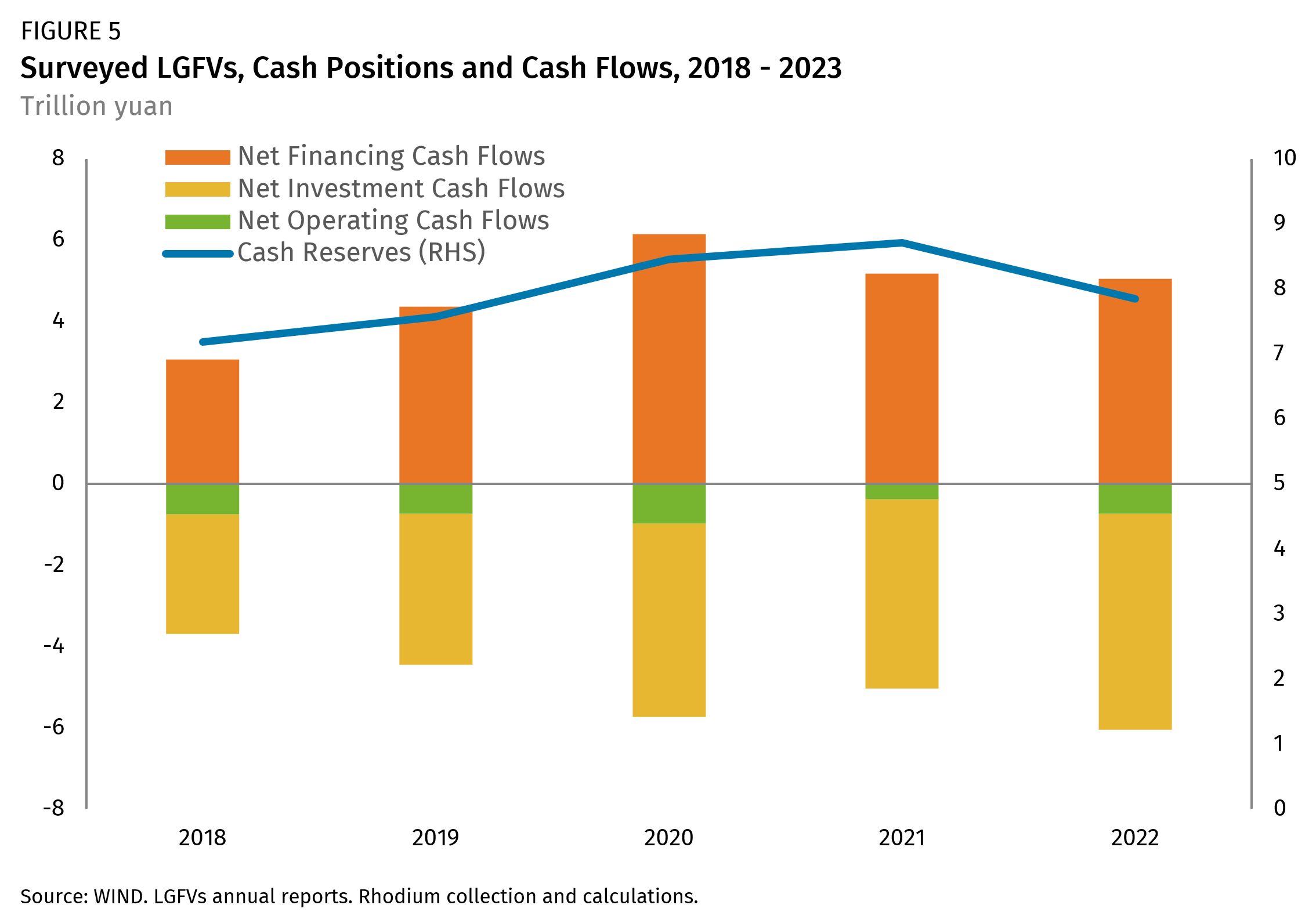

The most significant development in LGFV finances in 2022 was a decline in overall cash positions, from 8.7 trillion yuan at the end of 2021 to 7.8 trillion yuan, primarily due to net cash outflows of nearly 1 trillion yuan among surveyed firms (Figure 5). The last time LGFVs experienced a decline in cash was 2018, as deleveraging intensified, but this was a more modest decline of 58 billion yuan.

Stronger investment cash outflows in 2022 were responsible for the drop in cash positions. Net investment outflows reached 5.3 trillion yuan last year, nearly double the level in 2018 and up from 4.6 trillion yuan in 2021 and 4.8 trillion yuan in 2020. The increase in investment cash outflows is a result of LGFVs’ higher capital expenditures (capex) of 4.2 trillion yuan, as they were tasked with supporting growth in the second half of 2022. Infrastructure investment growth accelerated to 9.4% last year from just 0.4% at the end of 2021, with double-digit growth throughout the second half.

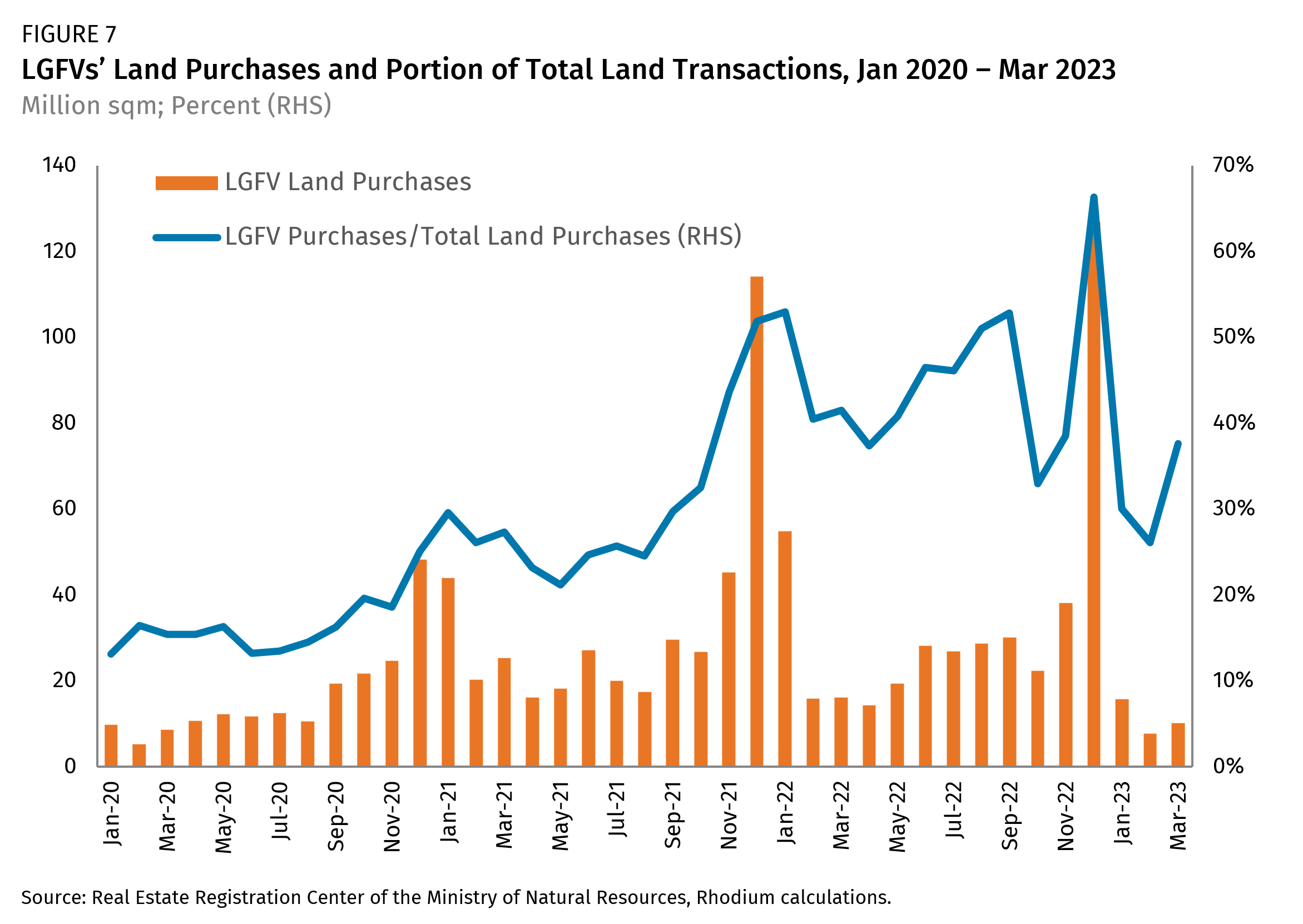

Another factor contributing to LGFVs’ rising capex was direct land purchases. Local governments utilized LGFVs to boost transactions in the land market last year to offset the decline in purchases by property developers.

Net financing cash flows dropped slightly to 5.1 trillion yuan as Beijing continued efforts to prevent local governments from accumulating new implicit debt. However, policy bank financing in the second half helped offset the slowdown in shadow bank borrowing. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) provided 740 billion yuan to fund infrastructure investments through policy banks, while commercial banks extended another 3.65 trillion yuan in credit lines to facilitate these policy bank loans last year.

Operating cash reported a net outflow of 734 billion yuan last year, nearly doubling the outflows seen in 2021, further impacting LGFVs’ cash positions. One key reason for the larger operating cash deficit was weaker direct support from local governments. Other operating cash flows, which typically include any real financial support that local governments can offer to LGFVs, only increased by 7.8% last year to 9.1 trillion yuan. This represents the slowest growth since at least 2017, compared to a 12.6% increase in 2021.

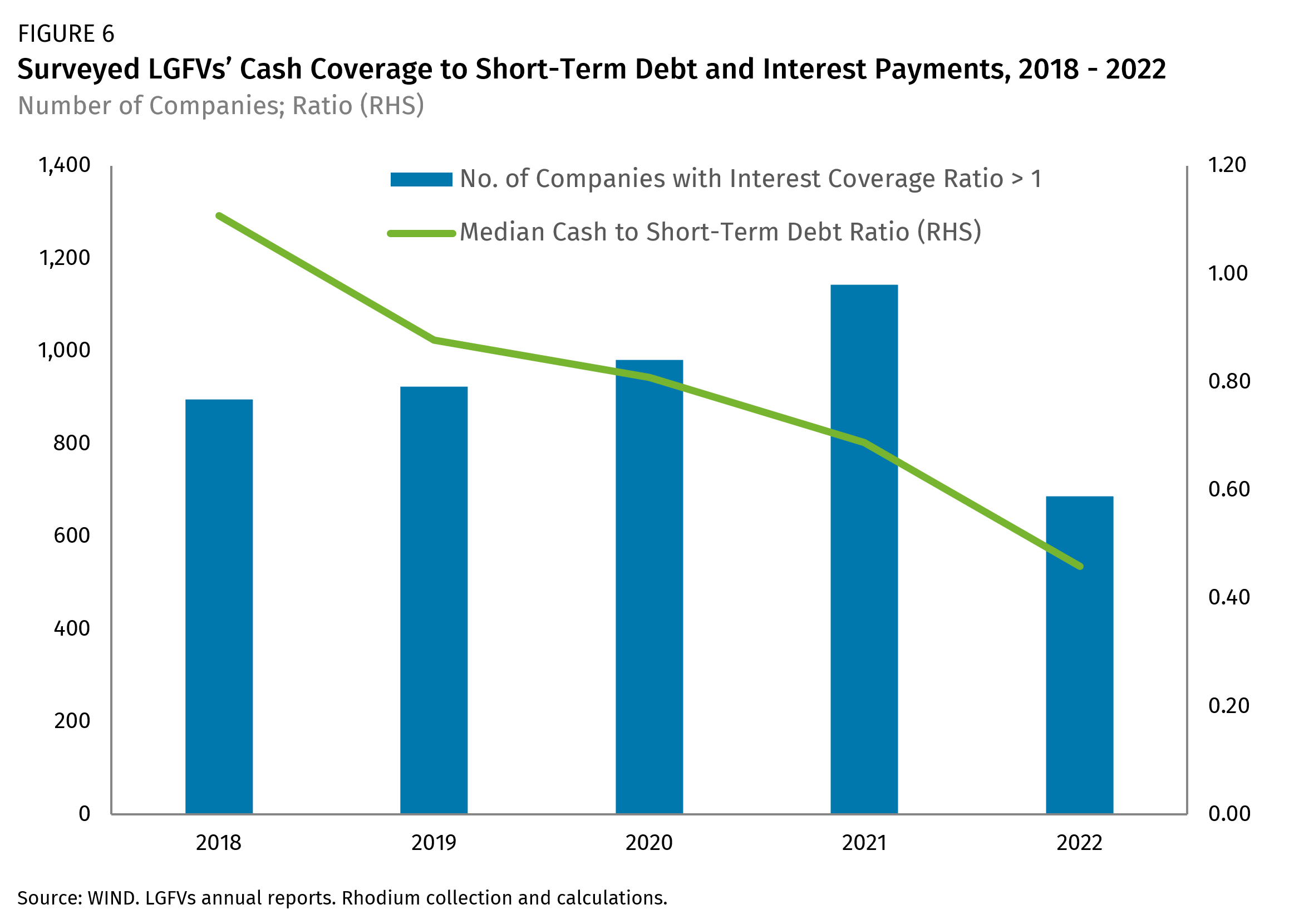

Larger debts and smaller cash positions have impacted LGFVs’ capacity to honor debt and interest payments. The median cash coverage ratio for short-term debt fell to 0.46 last year from 0.69 in 2021, with only 567 firms, or less than one-fifth of the surveyed sample, featuring a ratio above 1.0, indicating that their current cash position can fully cover short-term obligations. In 2021, this number was still 924 firms (one-third) and nearly half of the surveyed sample between 2018 and 2020. Similarly, only 687 companies have a cash flow coverage ratio for interest payments greater than 1, just over half as many as in 2021. Nearly four-fifths of LGFVs do not appear to have sufficient cash flows to cover interest payments.

Keeping Up with the Joneses: LGFVs and the Land Market

One of the most significant consequences of the property market’s two-year rout for localities was the decline in land sales revenues, which were 2.0 trillion yuan lower in 2022 than the previous year, and will decline further this year, given payments on land purchases are made with a one-year lag. As private developers have withdrawn from the market and state-owned developers slashed their land purchases, local governments have suffered. To create an illusion of prosperity in the land market and attract buyers, as well as to artificially inflate land sales revenues, local governments tasked LGFVs to buy considerable volumes of land last year (Figure 7).

Last November, the Finance Ministry had to issue a statement instructing local governments to stop using LGFVs to artificially inflate land transaction numbers, but this barely worked. LGFVs accounted for half of land purchases in 2022, compared to 33% in 2021 and 17% in 2020.

In LGFVs’ annual reports, land is typically categorized as inventory, property investment and intangible assets. Our surveyed samples saw total inventory increase by 11.4% to 44.4 trillion yuan by the end of 2022. This marks the first time since at least 2018 that inventory growth has accelerated.

The primary issue with LGFVs purchasing land is that they are not genuine developers. While some LGFVs are involved in the property industry, they are focused on land development rather than constructing and selling houses. The large volume of LGFV purchases is actually extending the adjustment of the housing market, by slowing the transformation of land into new residential properties. This has contributed to the ongoing decline in new starts by over 20% this year. According to data from the China Real Estate Information Company (CRIC), LGFVs only commenced construction on 38% of the land they acquired in 2021, which is significantly lower than the industry average of 67%, including state-owned and private developers. This ratio further declined to just 8% in 2022, coinciding with the decline in the industry average to 31%.

Restructuring and Growth

The most important variables impacting China’s economic growth over the next two years will be the success or failure of local government debt restructuring, and Beijing’s approach to the role of local government investment within China’s economy in the future. The current course, which China has used as an intrinsic element of its growth model over the past two decades, has reached its terminus, with more and more localities likely to follow the path of Guiyang and Hohhot in requesting bailouts. A collapse in local government investment would be comparable to the economic impact of the crisis in the property market.

Beijing has historically exercised control over the economy through the allocation of credit to state-owned enterprises and by channeling fiscal policy through local government investment. Local debt issues jeopardize these traditional levers of control. For China to again be able to rely upon fiscal policy to deliver growth, Beijing urgently needs to restructure local government debt. LGFVs’ financial results in 2022 highlight that no solution will emerge from localities themselves. Beijing would like to take its time with a deliberative process over the summer, but rising calls for help among localities may eliminate that luxury as more urgent actions to stabilize local finances are required.