The Undoing of US Climate Policy: The Emissions Impact of Trump-Era Rollbacks

President Trump has made dismantling environmental regulations a priority during his time in office. Rhodium Group has assessed the emissions implications for each of the major rollbacks.

President Trump has made dismantling environmental regulations a priority during his time in office. While some of these moves remain mired in legal uncertainty, the Trump administration has successfully unraveled the majority of Obama-era climate policies, including the Clean Power Plan, fuel economy standards for passenger vehicles, and efforts to curb potent greenhouse gases (GHGs) from refrigerants and air conditioning. Just last month, the administration eased regulations preventing methane leakage from oil and gas facilities. Rhodium Group has analyzed the isolated implications of each of these regulatory rollbacks on US GHG emissions in previous research. In this note, we examine their aggregate effect. We find that Trump’s major climate policy rollbacks have the potential to add 1.8 gigatons of CO2-equivalent to the atmosphere by 2035. This cumulative impact is equivalent to nearly one-third of all US emissions in 2019.

Unraveling Obama’s regulations

Having promised to cut environmental regulation on the campaign trail, President Trump wasted no time once in office. In March 2017, Trump signed an executive order directing then-Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) director Scott Pruitt to repeal and replace the Clean Power Plan (CPP), former President Obama’s signature climate policy, which aimed to cut GHG emissions from power plants. In his order, Trump also made clear his intention to roll back all other major climate policies of his predecessor. The announcement foreshadowed his June 2017 decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, by unwinding the major policies designed to achieve it.

Vehicle emission regulations

In March 2017, Trump unveiled his plan to scale back the federal fuel economy and GHG emission standards for passenger vehicles for model years (MY) 2021 to 2025. The original rule was expected to achieve fleet-wide fuel economy improvements of around 5% a year. Backing off an initial proposal to freeze standards at 2020 levels, the administration released its final Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) rule in March of 2020, which will increase the standard by 1.5% annually.

At the same time, the EPA and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) took steps to revoke California’s power to set stricter state vehicle emissions standards for vehicles. Rescinding California’s waiver could also end the state’s ability to set zero-emission vehicles (ZEV) sales standards that require automakers to offer a specific number of battery-electric, hydrogen fuel cell, and plug-in hybrid vehicles for sale each year. To date, 13 states and Washington, D.C. have adopted California’s vehicle standards and ZEV program. After the rollback was finalized in September of 2019, 22 states joined California in an ongoing lawsuit against the EPA.

Hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) regulations

The Trump administration has also taken steps to unravel controls on hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), powerful greenhouse gases used in refrigeration and air conditioning. In 2017, a federal court vacated part of a 2015 Obama-era EPA regulation that blocked the use of HFCs in certain applications. Shortly thereafter, the EPA stopped enforcing the rule entirely. In April of 2020, the DC Court of Appeals determined that the EPA had gone too far, and remanded the rules to the agency for further consideration. To date, the EPA has failed to propose a replacement. In March of 2020, the EPA also took aim at another Obama-era rule when it relaxed leak prevention requirements for HFCs under the Refrigerant Management Program (RMP).

The Obama-era regulations were designed to put the US on a path to complying with the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol—a multilateral agreement that sets targets for countries to slash the use of HFCs. The Kigali Amendment went into effect last year, but the Trump administration has failed to support its ratification in the Senate. The treaty has significant bipartisan and industry support, however, and just last week the Senate put forward a proposal that would phase down HFCs roughly in line with Kigali’s requirements. It’s yet unclear if both chambers will approve the proposal ahead of their January recess, and if so, whether Trump will sign it into law.

Methane regulations

In its latest move, the Trump administration further weakened regulation on methane emissions from oil and gas production. The rollback, announced in August of this year, eases an Obama-era 2016 EPA requirement that oil and gas companies track and prevent methane leaks from their operations. In response, a group of 20 states and four municipalities filed a lawsuit against the EPA this week. The EPA’s reversal comes on top of a rollback in 2018 to Bureau of Land Management (BLM) rules that limited oil and gas methane emissions on public land. A federal court ruling in July 2020 vacated the rollback and requires the BLM to reinstate the original rule by October. However, the Obama-era rule faces renewed legal challenges that could reinstate the stay. The EPA has further undercut methane controls by delaying enforcement of rules that aim to scale back methane emissions at municipal solid waste landfills.

The emissions impact of Trump’s rollbacks

For this analysis, we used RHG-NEMS, a version of the Energy Information Agency’s (EIA) National Energy Modeling system modified and maintained by Rhodium Group to capture all current state and federal policy—including rollbacks—and to reflect our own energy market and economic assumptions. Earlier this year, we modeled a range of post-COVID economic recovery scenarios designed to capture uncertainty in the pace of future economic growth in our Taking Stock 2020 report. Over the past few months, it’s become clear that key energy market indicators are most closely tracking with our “V-shaped” recovery scenario. This scenario assumes no federal or state-mandated shelter-in-place orders after the initial round of closures this spring. While much remains uncertain about the future of the disease, most states are pushing forward with reopening plans and the appetite for additional lockdowns has all but dried up. Many forecasters now believe a faster economic recovery is likely, as trends in hiring, consumer spending, and home sales exceed expectations. While much remains uncertain, this suggests that the V-shaped baseline is best-suited to capture the impact of COVID-19 on the economy, energy demand, and emissions.

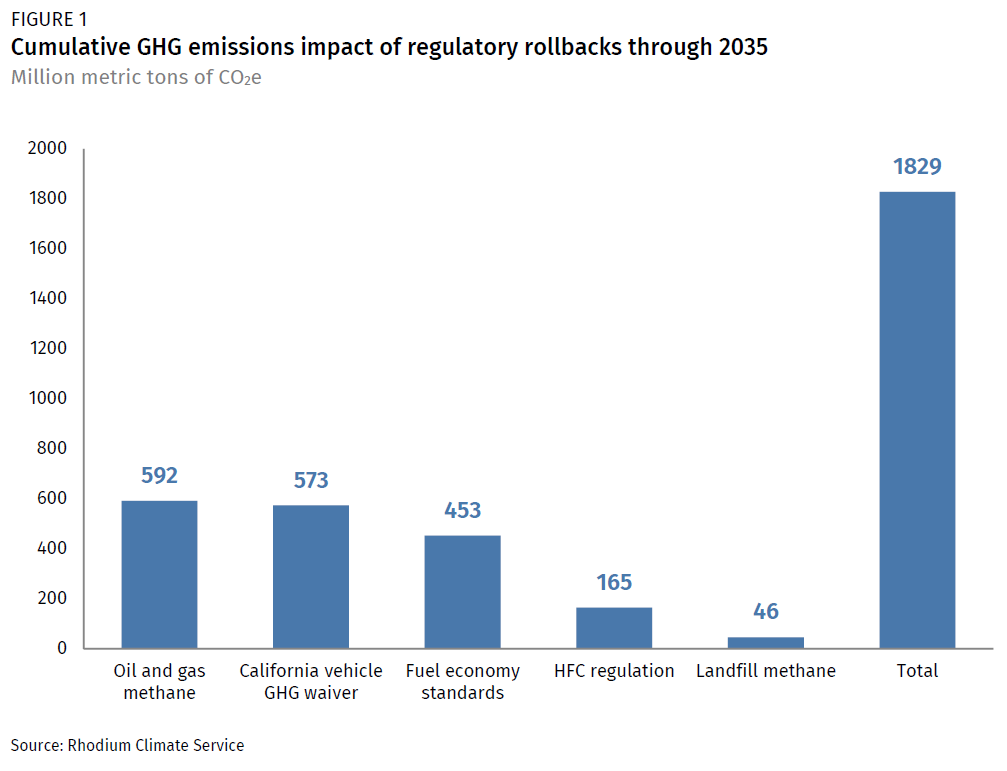

To understand the impact of Trump’s rollbacks, we compare national emissions projections with the rollbacks in place to projections with the original Obama-era regulations, using our V-shaped recovery scenario. For many of these regulations, the impact grows over time as more higher-emitting equipment (e.g. cars, A/C units, oil and gas facilities) comes online. For this reason, we look at impacts out to 2035. We focus on the cumulative impact of these policies over time, as opposed to the annual impact, because that’s what matters for the climate. We estimate that in the absence of new federal policy, Trump’s rollbacks will increase US emissions by 1.8 gigatons cumulatively through 2035 (Figure 1). This cumulative impact is equivalent to nearly one-third of all US emissions in 2019. As a result, total US emissions in 2035 will be 3% higher than they would have been absent Trump’s rollbacks.

Vehicle emission regulations

If the Trump administration successfully rolls back federal and state vehicle rules, we estimate that over one gigaton of additional GHG emissions will be released to the atmosphere by 2035. More than half of the impact results from striking down California’s waiver, including its ability to set more stringent vehicle emission standards and maintain the ZEV program. If California and its coalition states lose their ongoing lawsuit against the EPA and the waiver is revoked, this would increase emissions by 573 million metric tons (MMT), cumulatively, through 2035. Striking down the ZEV mandate accounts for nearly two-thirds of this impact, and would represent a significant hurdle to the burgeoning electric vehicle market across the US, leading to 5 million fewer EVs on US roads by 2035 (a 17% reduction from expected 2035 levels).

For the rest of the country, the emissions impact of replacing the Obama-era fuel economy standards with the Trump administration’s less stringent rules increases emissions by 453 MMT cumulatively through 2035.[1]

Hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) regulations

The Trump administration’s rollback of the Refrigerant Management Program (RMP) would increase HFC emissions by 165 MMT by 2035. We don’t include the partially-vacated 2015 EPA rule prohibiting the use of HFCs in certain applications, nor do we account for the Trump administration’s failure to ratify the Kigali Amendment, because we don’t consider these to be Trump rollbacks—the former is a court decision and the latter is an omission as opposed to a reversal. While not included in this tally, full implementation of the 2015 rule and compliance with the Kigali Amendment could reduce emissions by more than a gigaton cumulatively by 2035.

Methane regulations

We estimate that the weakening of the EPA and BLM oil and gas methane regulations would increase emissions by 592 MMT cumulatively through 2035.[2] We assume emission reductions for methane from municipal solid waste landfills rules are delayed—with enforcement starting in 2022 rather than 2016. This results in 46 MMT of additional methane emissions through 2035.

The repeal and replacement of the Clean Power Plan

We assess the impact of the Obama-era Clean Power Plan and the Trump administration’s replacement, the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule. However, we exclude the repeal and replacement from our rollback total in Figure 1, due to the high level of uncertainty in how each policy would be implemented in practice.

The CPP would have set emission reduction targets for the power sector for individual states, leaving it up to each state to determine their own compliance pathway. To analyze the repeal of the CPP, we compare our 50-state power GHG projections to state-level targets included in the original rule. Renewable costs have fallen sharply since these goals were set in 2015, making it easier for states to comply. However, we hold these targets constant at 2030 levels through 2035, though it’s likely that both pre- and post-2030 goals would have been raised to account for today’s more conducive energy market conditions. If all states took advantage of trading, the CPP as originally designed would be non-binding, delivering no emissions benefits. However, if states chose not to trade, we estimate the rule would have resulted in cumulative emissions reductions of 624 MMT CO2 through 2035.

The ACE rule, finalized in June of 2019, directs states to prioritize on-site, heat rate efficiency improvements in coal-fired power plants based on EPA technology guidelines. The rule could lower emissions by improving plant efficiency and by forcing operators that fail to comply to shut their doors. However, because the rule does not set specific limits on CO2, it may do little to stem power sector GHGs. In fact, by promoting efficiency, the rule could make coal-fired generators more cost-effective, boosting generation for some plants. However, our assessment shows the resulting rebound is offset by emission reductions associated with heat rate improvements and plant retirements. We estimate that the policy could result in zero to 383 MMT of CO2 reductions through 2035.

States help fill the gap

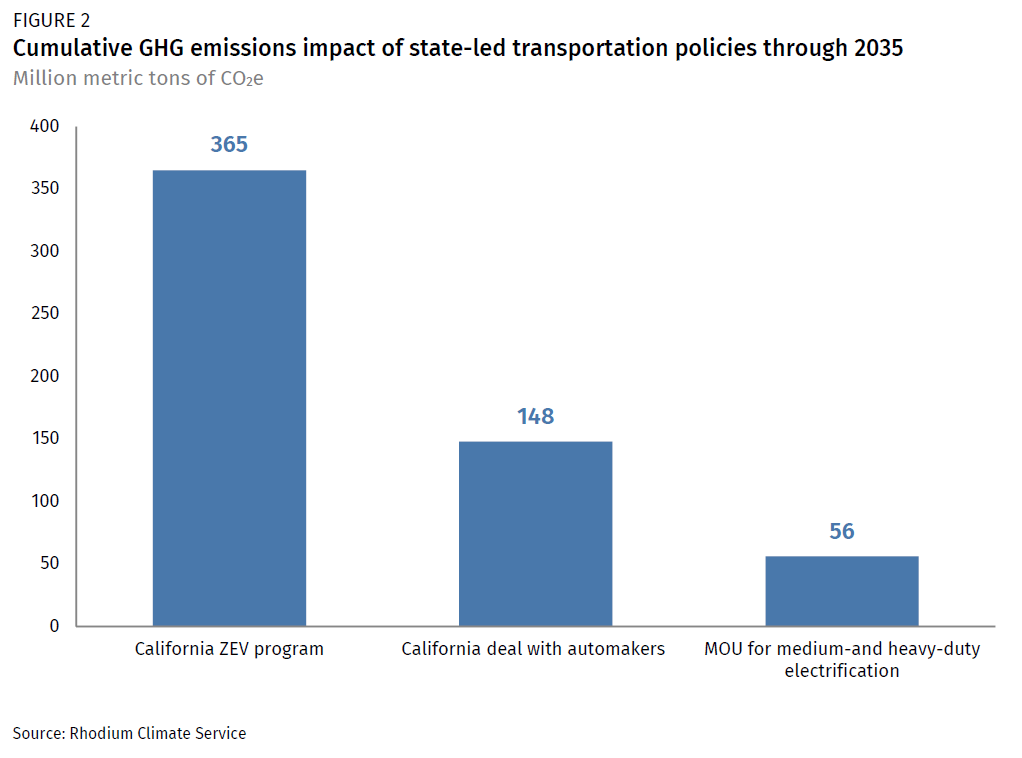

In the absence of federal climate policy, state capitals and city halls have taken on the fight against climate change. They have also waged a legal battle against the Trump administration’s rollbacks. Nowhere is this more apparent than in transportation, the sector most impacted by Trump’s climate rule reversals and the single largest source of US GHG emissions. While we assume that revoking California’s vehicle emissions waiver is final for the purpose of this analysis, a legal battle over the EPA’s decision rages on. Skirting the Trump administration all together, California reached voluntary agreements with five of the world’s largest automakers to increase vehicle emission standards nationwide, which we analyzed in a recent note. In August of this year, the deal became binding when the state signed a legal settlement with the automakers.[3] If California prevails in its legal battle to maintain its waiver, ZEV mandates, coupled with fuel efficiency standards under the deal, could mitigate a substantial portion of Trump’s tailpipe rollbacks (Figure 2). In the same note where we analyze California’s deal with automakers, we also find that a California-led 15-state agreement to accelerate medium and heavy-duty vehicle electrification would reduce transportation emissions by another 56 MMT over the same timeframe. Together, these policies could undo almost a third of the damage of the full suite of Trump’s climate rollbacks.

Despite Trump’s actions, we find that pre-COVID, US emissions were on track to fall 4% over the course of his first term. Much of this progress can be attributed to cheap natural gas and the rapidly falling cost of renewable energy technologies. As clean technology costs continue to fall, they will bring previously long-shot climate goals more within reach. For climate-forward states facing budgetary crunches during the pandemic, this may be good news.

Reaching long-term climate goals, however, will almost undoubtedly require a concerted federal effort. What’s more, our analysis of federal rollbacks likely underestimates the climate implications of the Trump administration, for two reasons. The first is that the rollbacks we consider here are far from exhaustive. The current administration has reversed many more Obama-era rules with climate implications that are difficult to assess. In 2017, for example, the Trump administration ordered agencies to stop using an Obama-era social cost of carbon—the cost to society from each ton of CO2 emitted—in cost-benefit analyses. This could have far-ranging effects on policy design and the allocation of funding to mitigate GHG emissions, but the projected emissions impact is difficult to quantify.

The second reason we likely underestimate Trump’s climate reversals is that, as we highlight above, energy market forces have worked in the opposite direction. These market forces have made many Obama-era policies now seem weak as originally designed. A climate-friendly successor would likely have increased the ambition of Obama’s rules. But without knowing how, our analysis likely understates the true climate cost of Trump’s rollbacks relative to the alternative. A future federal administration will need to go beyond reinstating policies that the Trump administration has rolled back and also set higher levels of policy ambition that take new market realities into consideration.

[1] In a recent assessment, we found that replacing the Obama-era fuel economy standards with the Trump administration’s Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) rule could result in more than 600 million metric tons (MMT) of additional GHG emissions by 2035, if implemented nationally. In that total, we account for revoking California’s waiver to set stricter fuel economy standards, but not for revoking the ZEV mandate. This is why the results differ here.

[2] This impact represents an upper bound estimate because it is based on an earlier, proposed rollback of aspects of the 2016 EPA regulation, which goes further in weakening the original standard than the version of the rules finalized in August 2020.

[3] California’s automaker deal is designed to remain in place regardless of the outcome of its legal battle to maintain its waiver.