Tipping Point? Germany and China in an Era of Zero-Sum Competition

The shifting economic relationship between Germany and China could have outsize impact on the direction of European policymaking toward Beijing.

In the first two decades of the 21st century, the German and Chinese economies were as complementary as two major economies can be. In recent years, however, this dynamic has begun to shift in important ways, with China emerging as a formidable competitor to Germany in the industries it once dominated. What for years felt like a win-win economic relationship, to borrow one of Beijing’s favorite expressions, is trending increasingly in the direction of zero-sum. Looking ahead, German firms are likely to see their market shares in China erode, while coming under significant pressure from Chinese competitors at home and in third markets—a dynamic that is likely to have ripple effects for the bilateral relationship. Against the backdrop of a stagnating German economy and more volatile political environment, job losses in key German industries could trigger a backlash that has been largely absent until now, even as the government line on China has hardened. In this note, we explain how the economic relationship between Germany and China is changing, and assess the implications of these changes for Germany’s and Europe’s approach to China in the years to come.

From win-win to zero-sum

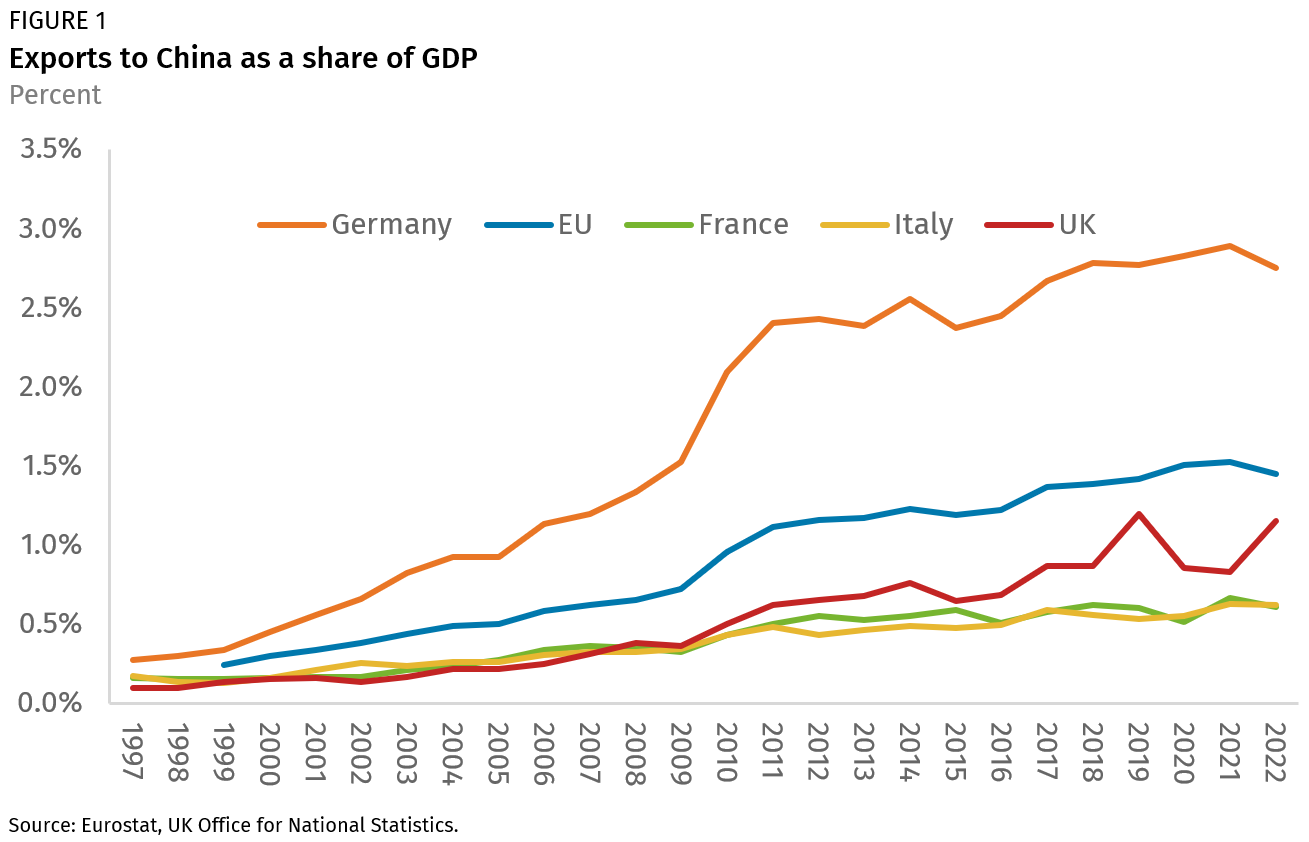

Germany and China have developed a strikingly close economic relationship over the past decades, fueled by booming bilateral trade and tens of billions of euros in investments by German manufacturing companies in the world’s second largest economy. Germany’s exports to China account for a much larger share of the country’s GDP than the exports of other European countries (Figure 1). Between 2009-2021, German exports to China surged from 52 billion euros to a record high of 123 billion euros, nearly double the combined exports to China of France, the United Kingdom, and Italy. German direct investments in China also multiplied, hitting a record 7.1 billion euros in 2022 (they averaged 3.7 billion annually in the decade from 2011-2020), according to Rhodium Group estimates. Between 2016-2023, Germany’s share of total EU FDI in China averaged 58 percent, up from an average of 38 percent in the previous decade.

The foundation for this close trade and investment relationship was the complementarity of the two economies. German industry delivered the cars, machine tools, and engineering know-how that an emerging China needed to grow. And surging demand from China filled the order books of German manufacturers, creating well-paid German jobs and helping transform the country from the sick man of Europe into the continent’s growth locomotive. When Europe was hit by financial crises in the 2009-2013 period, demand from China helped insulate the German economy from the blows suffered by other EU member states.

Some German industrial sectors—construction, cement, steel, rail, and solar—began feeling the bite of Chinese competition and market access restrictions over a decade ago, leading to bankruptcies and job losses. But the struggles of these industries were largely overshadowed by the positive momentum in other sectors, like cars and machine tools, as well as by the overall strength of the German economy. This created a unique alignment of Germany’s political establishment, its biggest companies, and hundreds of thousands of industrial workers in favor of robust economic engagement with China. While the United States was suffering a “China shock” in the decade after Beijing’s entry into the WTO, leading to the estimated loss of 560,000 US manufacturing jobs, German industry was booming on the back of strong demand from China.

Fast forward to 2024, and the China pact between German politicians, companies, and workers is beginning to show cracks. Some German companies, notably small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), have soured on the Chinese market because of geopolitical tensions, rising compliance costs, and policies that favor home-grown firms. Others that continue to do well in China, notably in the automotive sector, are coming under pressure in their largest market from fierce local competition. In July 2023, the German government published a China strategy that advocated for economic diversification away from China.

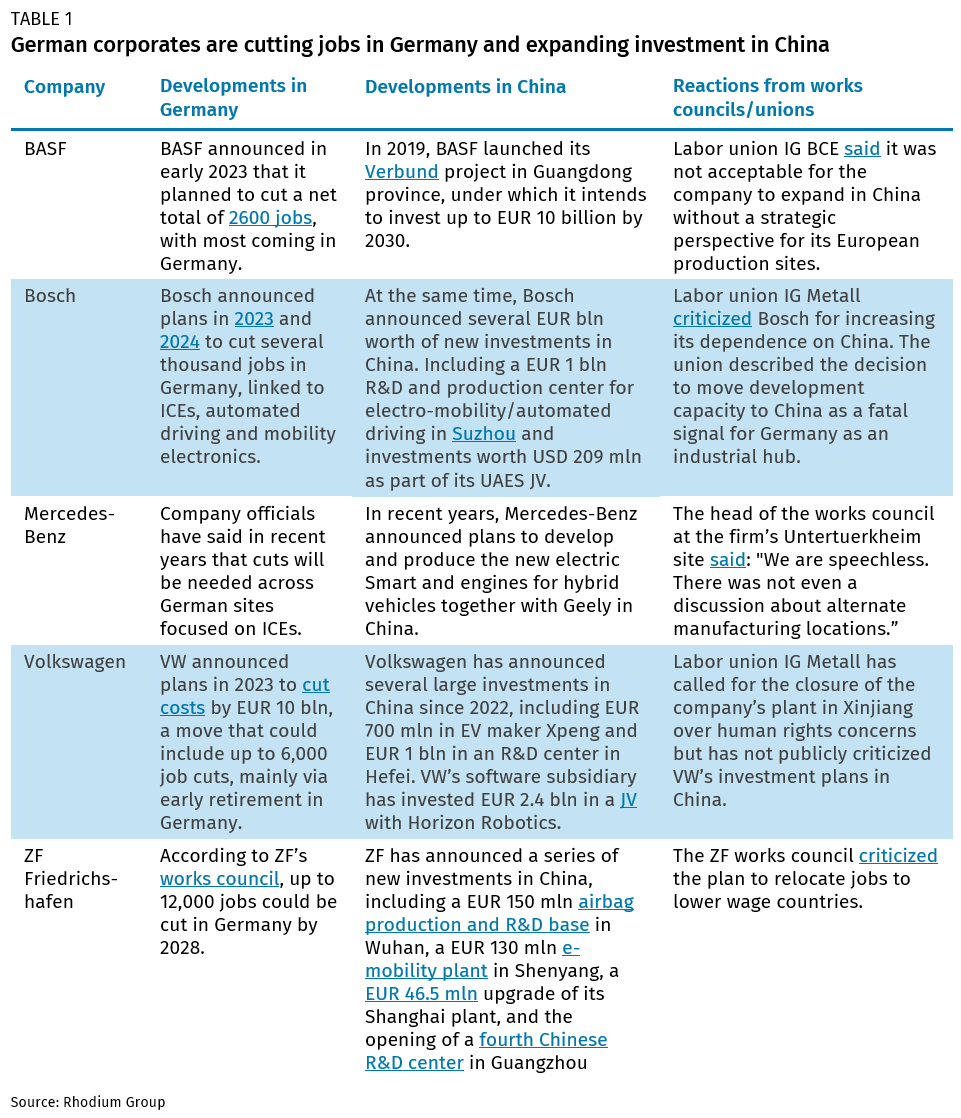

Despite a souring mood, big German firms have continued to invest heavily in China in order to remain relevant in a cut-throat market and to insulate their China operations from escalating geopolitical tensions. In contrast to years past, however, this is now being accompanied by thousands of job cuts in Germany, in part to adapt to the switch to electric vehicles (Table 1). German automotive supplier ZF Friedrichshafen, for example, is cutting up to 12,000 jobs in Germany, while seeking to boost the share of revenues it makes in China from 18 percent to 30 percent by 2030. This has led to protests by the company’s German staff. BASF and Volkswagen have also announced plans to downsize in Germany while increasing investment in China.

The job cuts are a result of rising economic pressures at home, linked to high energy prices and rising regulatory hurdles, as well as a response to staff levels in Germany that are increasingly out of line with market dynamics. They also reflect a rapidly evolving competitive landscape with China that has seen Chinese companies like BYD and CATL accelerate past German rivals in the development and production of electric vehicles and batteries. The same dynamic is playing out in other sectors, like machinery, where Germany has long played a dominant role.

China will remain an important economic partner for Germany for years to come, and the profits that German companies make in China will continue to support employment in Germany, cushioning what promises to be a bumpy transition to a green economy. Germany’s social market economy model, in which labor unions play a role in corporate decision making, will likely shield German workers from the extreme disruptions experienced by their manufacturing counterparts in the United States in the early part of the century.

But Germany may be nearing a tipping point, where the political and corporate forces advocating for a deepening of engagement with China will gradually give way to a more defensive approach, including the embrace of protectionist trade measures at EU level and more robust industrial policies. Three trends are likely to fuel this shift: falling German exports to China, shrinking margins and market share for German firms in China, and rising competition with China in global markets.

German exports to China

There are signs that German exports to China are entering a period of structural decline due to shifting competitive dynamics in the car industry, China’s import substitution policies, and a localization wave by German firms in China. This could lead to a gradual erosion of the link between Germany-based production and China-based sales.

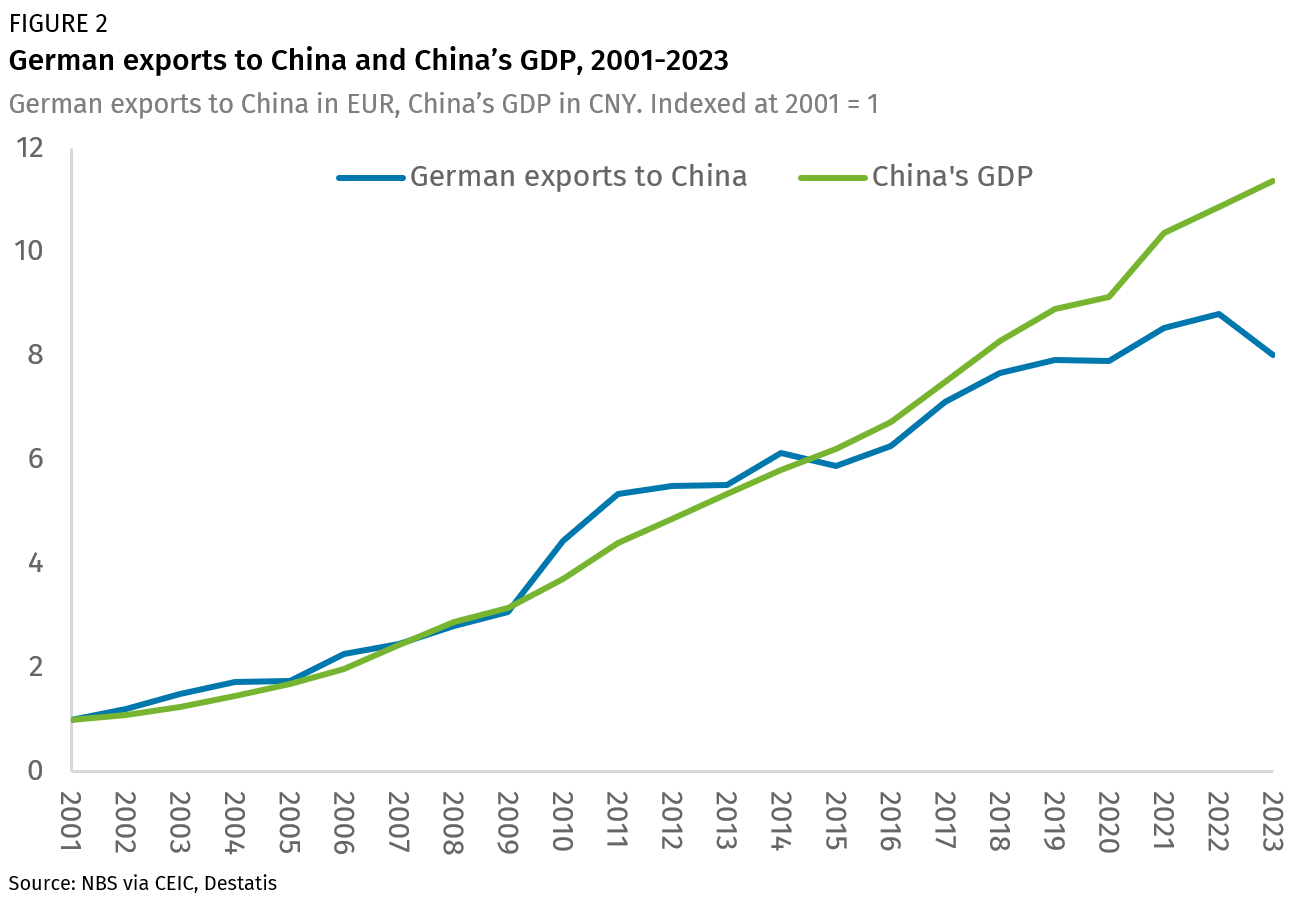

German exports to China expanded by double digits in the 1990s and 2000s, but growth began slowing a decade ago. After peaking in 2022, exports fell by nine percent in 2023 despite continued economic growth in China—by far the steepest decline since China joined the WTO (Figure 2). One reason may be slowing growth in China (see Dec 29, “Through the Looking Glass: China’s 2023 GDP and the Year Ahead”). But there are also drivers that are specific to the Germany-China trade relationship.

Not all companies and sectors would be affected by a structural downturn in exports in the same way. In industries where China continues to lag, for instance measurement devices or pharmaceuticals, German firms may continue to benefit for years to come from a robust export business with China. But the window has begun to close in sectors like automotive and electronic equipment, where the competitive landscape is shifting. China’s imports of automotive parts, the second biggest sector for imports from Germany after cars, declined by 22 percent between 2021 and 2023. Germany’s electro and digital industry association ZVEI reported that between January and November 2023, German electronic equipment exports rose 3.8 percent globally but declined by 3.5 percent to China. For large firms, this may be offset by the sale of goods produced in China. But for the Mittelstand, the SMEs that form the backbone of the German economy, local production is not always an option.

For Germany’s manufacturing industry and the value-added that it contributes, this presents a major challenge. According to the OECD, 450,000 German manufacturing jobs depended on Chinese demand in 2020. Going forward, these jobs are likely to come under growing pressure, with SMEs in the machinery and automotive industry feeling the strain most acutely. Should this trend continue, and should these firms struggle to diversify their export markets—a challenge given the difficulty of replacing a market the size of China and given rising competition from Chinese companies in third markets (explained in more detail below)—downsizing and insolvencies may be inevitable.

Market share and margins in China

In recent decades, the Chinese market has been a gold mine for German industrial companies, compensating for weaker demand and tighter margins at home and in Europe. But this China bonanza was built in an environment where the Chinese economy was growing strongly, where local competitors did not pose a major threat, and where the need for German technology and know-how was higher. Going forward, the operating environment is likely to be far more challenging, with the margins and market shares of German firms in China coming under increasing pressure. Over time, this could undermine the narrative that made-in-China profits “subsidize” German jobs and innovation.

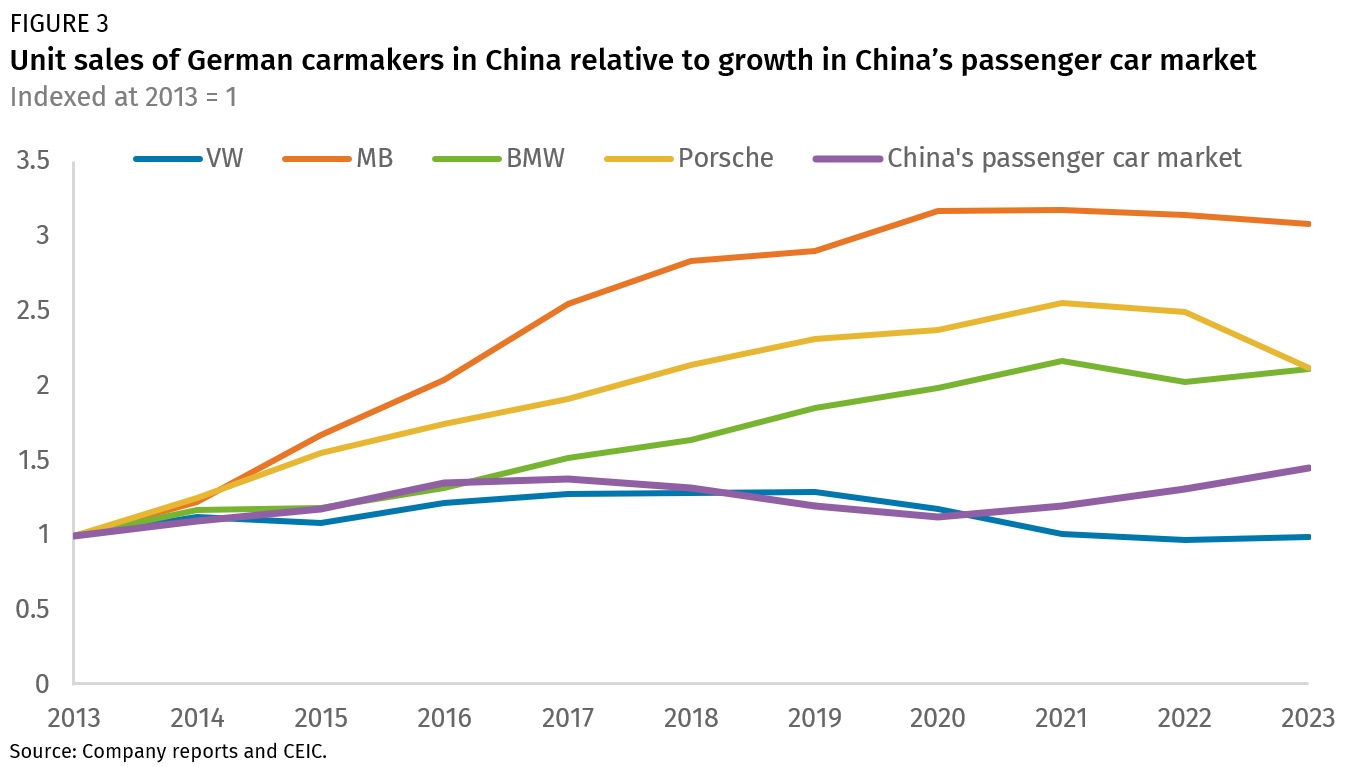

Take German carmakers, whose market share in China has fallen by four percentage points since 2018 (Figure 3). The losses have come mainly from volume producer Volkswagen, which sold fewer cars in China in 2023 than it did in 2013. Last year, China’s passenger vehicle market grew by 5.6 percent, but Volkswagen’s China JV profits likely fell to their lowest point in a decade, below even 2020 levels when the country was experiencing waves of pandemic-related lockdowns. German luxury carmakers have performed better than Volkswagen but are also facing a more challenging environment, as Chinese consumers embrace Chinese brands that are venturing into the luxury segment.

Pressure on market share and revenues has put pressure on profits too, leaving less money to send back to Germany. This dynamic has been reinforced by companies re-investing their made-in-China profits in the country in a push to remain competitive. Bundesbank data suggests that a growing share of corporate earnings are staying in China. Companies like Volkswagen and German chemicals group BASF may never become German versions of Nestlé—the Swiss food and beverage company that records less than two percent of its sales in the Swiss market. But the firms are in the process of reducing their footprint in the German market while increasing China-based jobs, R&D and, in some cases, production of goods destined for export. The surge in investment in China, and recent wave of downsizing in Germany, suggests that a gap is emerging between the financial interests of some German corporations, on the one hand, and the interests of their Germany-based staff and the broader German economy, on the other.

Competition from China in third markets

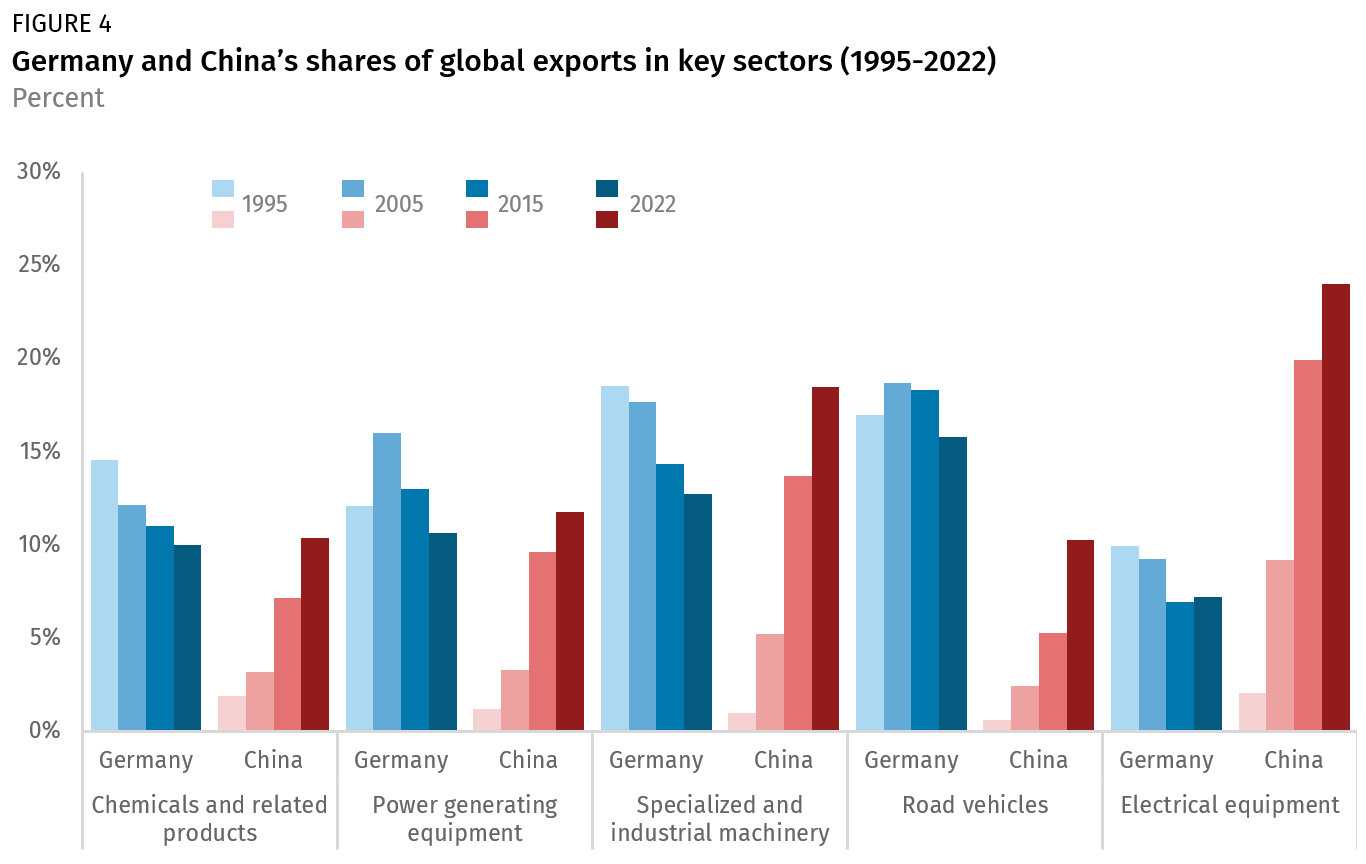

Lastly, German companies face a new era of fierce competition with Chinese rivals in third markets, from Latin America, the Middle East and Southeast Asia to Europe. In the past, Chinese companies struggled to compete with highly specialized German machinery companies, manufacturers of internal combustion engine vehicles, and producers of specialized chemicals. That is now changing. In motor vehicles, China is catching up quickly, and in exports of advanced manufacturing goods, China has already surpassed Germany (Figure 4). This could reinforce the view of China, in German corporate boardrooms and among German workers, as a source of unfair competition that is undermining German jobs and prosperity.

A large share of China’s gains have come in emerging markets (most recently in Russia after German firms pulled out of the market following Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine) due to price competitiveness and policy support from Beijing. While German machinery exports to BRIS countries (BRICS excluding China) and ASEAN are down 23 percent and 14 percent, respectively, compared to 2019, Chinese machinery exports have risen by 89 percent and 31 percent.

China has also gained market share in Europe, which accounts for two-thirds of German exports, at Germany’s expense. This is evident in the erosion of the bloc’s trade surplus in passenger vehicles, which relies heavily on German exports (Figure 5). Notably, in Germany’s domestic market, electric vehicles manufactured in China are gaining momentum, accounting for 11.7 percent of newly registered EVs in 2023. These include models such as BMW’s iX3 and the Mercedes-Benz Smart, underscoring how even German carmakers are producing in China to serve their domestic market.

China’s export competitiveness has been driven by several factors, including:

- China is catching up technologically in many high-tech industries. According to a recent survey from the German Chamber of Commerce in China (AHK), 51 percent of German firms operating in China believe Chinese competitors will become innovation leaders in their sector within the next five years, up from 36 percent in 2018. In the automotive sector, 69 percent of respondents consider Chinese companies already leading or ahead within the next five years.

- Overcapacity driven by massive capital investment in new production sites and slowing domestic demand.

- Subsidies and below-market inputs for energy and financing as well as strong policy support for exports. China’s state-owned export credit insurer Sinosure and policy bank Eximbank have in recent years ramped up export support for Chinese manufacturing companies and BRI projects generate overseas demand for Chinese products.

Third-market competition from China will affect all of Germany’s important export sectors and impact small and large firms. Of the three pressure points detailed above, third market competition could also have the largest impact on Germany’s value added as Germany’s manufacturing sector is highly export-oriented and although China is an important market, it is only one of many.

A German Tipping Point on China?

A decades-long period in which the German and Chinese economies were characterized by a high degree of complementarity is coming to an end. Looking ahead, the bilateral relationship is likely to be defined by an intensifying industrial competition, which will put pressure on German manufacturing companies in sectors they once dominated. German exports to China, which doubled over the past decade, could enter a structural downturn over the coming years. German profit margins in China are likely to come under growing pressure. And competition between Germany and China in third markets will continue to intensify. In contrast to a decade ago, when competition from China led to upheaval in sectors that were important but not vital to the health of the broader economy, current dynamics are likely to hit Germany where it hurts most: in the automotive, machinery and electrical equipment industries.

This new era of competition is emerging against the backdrop of a stagnating German economy, a more polarized political environment, and growing signs of social and labor unrest. German manufacturing jobs are being lost due to Chinese competition and a shift of corporate investment out of Germany and into China. This volatile cocktail increases the risks of a broader backlash against China—similar to the dynamic that emerged in the US over a decade ago as manufacturing jobs vanished—that includes more German companies and the hundreds of thousands of workers they employ.

Until now, German pushback against China has been largely a top-down phenomenon, driven by government concerns about resilience and security. In the future, the economic relationship is likely to become a greater source of tension, with industrial actors supporting rather than obstructing a more robust policy. A broader backlash would have important implications for Europe’s positioning on China, given the centrality of Germany in the EU-China relationship. Going forward, we expect Berlin to take a more active role in pushing back against China’s unfair trade practices, promoting more ambitious industrial policies in Europe, and embracing other EU-led measures to level the economic playing field.