US Decarbonization Priorities in the Wake of the Inflation Reduction Act

The Inflation Reduction Act has kicked off a new phase of decarbonization in the US, but on its own it won't be enough to achieve the US's 2030 climate target. We provide a framework for priorities in the decade ahead.

The passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) kicked off a new phase of decarbonization in the US. This single largest action to date to reduce US greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will accelerate climate progress in the US, but on its own, it won’t be enough to get the US on track to meet its 2030 climate target of reducing emissions by 50-52% below 2005 levels. Given that 2030 is only seven years away, actions taken in the next year or two will be highly consequential. But what can be done to make the most of the opportunities presented by the IRA? And what additional actions can further accelerate emission reductions and put the 2030 climate goal within reach? In this note, we provide a framework for prioritization and examples of possible actions. We find that, first and foremost, swift implementation of the IRA with a focus on maximizing clean energy deployment is key. On top of that, there are several policy opportunities that can help to close the gap to the 2030 target. When prioritizing new decarbonization opportunities, it’s important to focus actions on emissions sources where the IRA alone doesn’t deliver a lot of reductions but does incentivize clean technologies.

The IRA ushers in a whole new ballgame

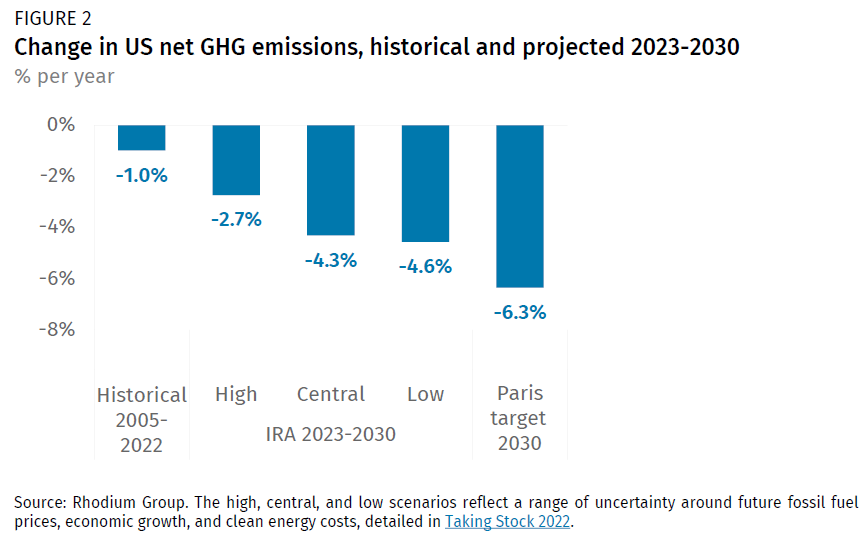

The hundreds of billions of dollars in long-term incentives and tax credits contained in the IRA represent a step change in US climate action. Our in-depth assessment of the IRA found that the package cuts net GHG emissions to 32-42% below 2005 levels in 2030—a 7-10 percentage point gain compared to a world without it. The reduction range reflects uncertainty around future fossil fuel prices, clean technology costs, and economic growth (represented as our high, central, and low emissions scenarios). Uncertainty aside, it is clear that the IRA accelerates the pace of US decarbonization.

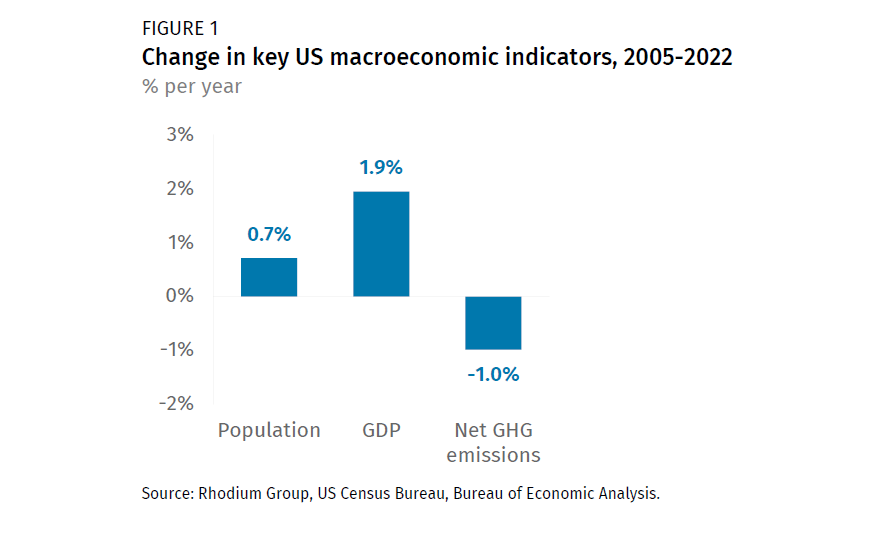

From 2005 through 2022, the US averaged annual net GHG reductions of 1%. Considering that there was no major federal climate legislation in that timeframe, and US GDP rose by 1.9% per year and population by 0.7% per year, it’s remarkable how much progress toward decarbonization the US achieved (Figure 1). The gains were the result of a variety of factors, including cheap natural gas and ever-cheaper renewables displacing coal in the electric power sector, increasing efficiency of vehicles and appliances, state clean energy policies, federal tax credits, and the continuation of a macroeconomic shift away from heavy manufacturing towards the less carbon-intensive service sector. Historical experience dispels the myth that decarbonization is not compatible with growth. It also suggests that faster decarbonization is possible with deliberate policy action in place.

Looking ahead to the rest of this decade, we find that the IRA will accelerate emission reductions to a level never previously experienced. Average emission reductions are on track for a pace of 2.7 to 4.6% per year across our emissions scenarios (Figure 2). That means that on average, every year moving forward will see decarbonization more than twice as fast as the pace since 2005 and as much as more than four times faster. We should expect nothing less from the biggest single action on climate change in US history. However, the US will need to move even faster to achieve the 2030 climate target of reducing emissions by 50-52% below 2005 levels, which would require an over 6% average annual reduction pace to keep the target within reach.

Where to start?

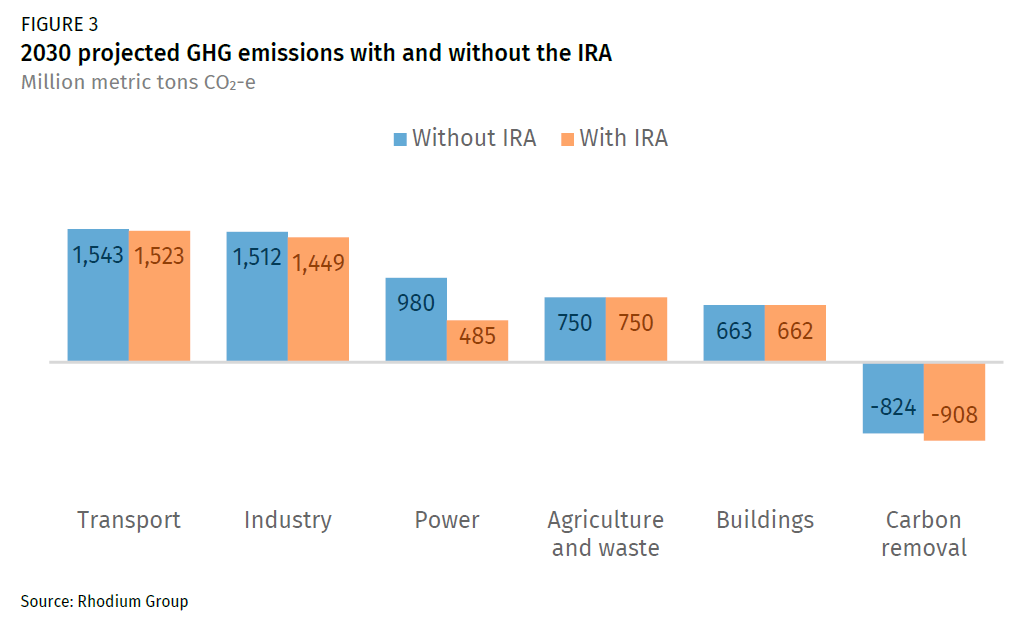

When considering additional actions in the US to meet the 2030 target, the first thing to do is make sure the IRA actually delivers what we estimate is possible, through swift and effective implementation. The vast majority of emission reductions from the IRA occur in the electric power sector (Figure 3). This means any IRA programs that drive electric power decarbonization need to be implemented quickly and robustly to get as much clean generation on the grid as fast as possible. The industrial and carbon removal sectors are also important sources of emission reductions. So where to start?

Speedy implementation

Staff at the Department of Agriculture, Department of Energy, Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Treasury, and elsewhere across the federal bureaucracy are working hard to implement their congressional marching orders from the IRA. Speed is of the essence. The sooner project developers and manufacturers have clarity and certainty as to how new IRA programs and tax credits work, the sooner they can leverage private capital to accelerate clean energy deployment and cut emissions.

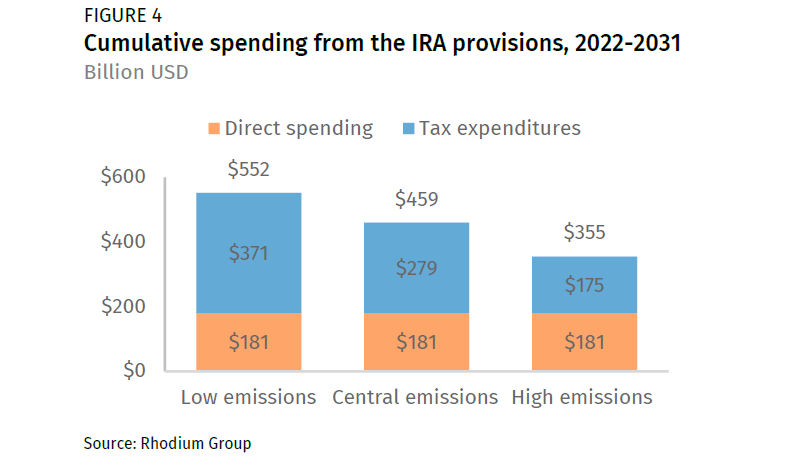

The most important center of activity from a decarbonization perspective is the Department of the Treasury, and in particular the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The vast array of expanded and new tax credits within the IRA all fall within the IRS’s purview. One important feature of tax credits is that, for the most part, the amount of federal expenditure is driven solely by qualifying installation or use of clean energy technologies. Put another way, the more solar panels installed and electric vehicles (EVs) on the road, the higher the investment by the federal government with no upper limit. This sets tax credits apart from the rest of the IRA where direct spending on grant programs, loans and other mechanisms have specific caps set by Congress.

Across our three emissions scenarios, we find that through 2031, tax expenditures generally represent the majority of federal spending under the IRA. The final official score from the Congressional Budget Office and Joint Committee on Taxation said that the IRA clean energy and climate investments would cost $383 billion over ten years. Our corresponding estimate from our high emissions scenario is in the same ballpark at $355 billion, split roughly 50/50 between direct spending and tax expenditures. In our central and low emissions cases, total spending is higher than official estimates as we project tax credits drive more clean energy deployment, ending up with total spending of $459 billion and $552 billion respectively. Tax expenditures represent 60-67% of all spending in these scenarios. In other words, up to two-thirds of IRA investments are in the hands of the IRS. All of the implementation decisions this agency makes over the next few years from clean hydrogen to electric vehicles to battery production will have an outsized impact on the pace of decarbonization in the US in the 2020s and beyond.

Walking the tightrope

In implementing IRA provisions, the IRS will have to walk a fine line and balance many factors beyond decarbonization. International trade dynamics, supply chain security, labor relations and administrative practicalities are all in tension. One does not have to look far to find examples. The IRS recently indicated that it would interpret language in the IRA to allow leased vehicles to qualify for the commercial clean vehicle tax credit (45W) rather than the more restrictive clean vehicle credit (30D). Broader availability of tax credits for EVs accelerates deployment, all else being equal, in turn driving greater emission reductions. But this decision raised concerns about supply chain security from Senator Joe Manchin and at the same time is in line with requests from trading partners.

There are also concerns surrounding the implementation of emerging clean technology credits, such as the clean hydrogen credit. Deployment of emerging clean technologies starts from a very small base and, in general, initial projects are quite costly to build because of a lack of supply chains, experience, and scale. They are at the top of the learning curve and many have the potential to see dramatic cost reductions as deployment accelerates—similar to what we’ve seen for solar, wind and batteries over the past 15 years. As the IRS implements the IRA, it will have to balance the need to expand emission reduction opportunities over the long-term with near-term GHG implications. Overly strict, near-term rules that maximize the environmental integrity of the first wave of projects may stifle deployment and cost reductions from learning, as well as forfeit innovation. At the same time, failing to ensure that implementing regulations addresses outstanding climate and environmental concerns could lead to blowback from advocates and Congress, as well as unintended increases in emissions down the road. A phased-in approach that unleashes investment quickly while raising the environmental performance bar in a predictable manner over time could be one way forward.

These same challenges apply to direct spending programs under the IRA as well. For example, DOE is currently determining how to spend $5.8 billion on a new advanced industrial facility deployment program. The Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations is wrestling with whether to focus the money on deployment of commercial technologies across the sector or to go for big transformational investments in getting a few emerging clean technologies down the learning curve. New grant programs elsewhere at DOE, EPA and other agencies also face similar trade-offs. If these programs are going to maximize innovation and emission reductions, it will be important to avoid redundancy with other IRA provisions and make sure each investment leads to additional technology deployment.

The next wave of action

Even with speedy and successful implementation of the IRA, the US still has a long way to go to achieve its 2030 target of reducing emissions 50-52% below 2005 levels. Fortunately, there is no shortage of additional policy actions that executive branch agencies, states, the private sector, and the new Congress can take to further accelerate decarbonization and put that target within reach. A range of policies can fortify and amplify the gains made in the IRA, but a host more will be required to achieve additional reductions beyond the IRA.

There are a few strategies to consider in any push to achieve additional emission reductions above and beyond the IRA. These include:

- Overcome non-cost barriers to clean technology deployment. The IRA makes most clean technologies cheaper than fossil alternatives, but cost isn’t the only thing inhibiting rapid deployment. Siting, permitting, lack of information, principal-agent problems, workforce bottlenecks, supply chain constraints and other barriers all stand in the way of maximizing clean energy deployment. Overcoming any of these headwinds will increase the impact of the IRA and cut carbon pollution. We plan to take a closer look at these issues in a forthcoming research note.

- Target sectors that don’t see many IRA-driven reductions. Based on our analysis, we see only small decarbonization gains in the sectors of transportation, buildings, and agriculture & waste, making them prime targets for additional action.

- Target sources that aren’t affected much by the IRA. Our analysis finds that even the enhanced IRA tax credits generally don’t incent fossil fuel-fired power plants and large sources of fossil fuel combustion in industry to install carbon capture. New requirements to install such equipment could lead to additional reductions and IRA tax credits can reduce the cost of compliance. Emissions sources could see similar opportunities with other clean technologies.

- Target opportunities where IRA incentives lower the cost of action. Revamping state and federal energy efficiency and transportation programs to prioritize electrification should be easier with cost reductions from IRA incentives, driving more technology deployment beyond what the IRA alone can accomplish. There may be more opportunities in other sectors.

We modeled a range of policies in addition to a major congressional investment in our October 2021 report, Pathways to Paris: A Policy Assessment of the 2030 US Climate Target. Many of the actions we considered fit within one or more of the strategies listed above. We plan to revisit that analysis with fresh eyes later this spring.

This next chapter is different

The IRA is such a consequential piece of legislation that it is worth taking a moment to recalibrate before pushing hard for policies from the same old playbook. Strategic prioritization of new policy actions that leverage the IRA and target emissions, bottlenecks, and barriers that the IRA doesn’t touch will be essential to accelerating decarbonization—not just for the sake of making progress in this decade, but also to expand the range of opportunities over the long-term. Given all the work ahead, it is also not the time to be considering major funding cuts to agencies and departments at the federal and state level where a lot of the action resides. Big federal legislative wins don’t come easy or often, especially in climate policy. Any progress beyond the IRA can cut emissions and expand the space for the next wave of policy action. It’s time to get to work.