US-China Trade War, Volume 2

In deploying a fresh wave of duties on a short list of strategic products, the Biden administration is highlighting the China dependencies that it wants to break while also inadvertently providing China with a target list for retaliation.

With six months to go until the US election, the Biden administration on May 14 announced steep tariff hikes targeting a short list of strategic imports from China, covering steel and aluminum, semiconductors, electric vehicles, batteries, critical minerals, solar cells, ship-to-shore cranes, and medical products. While bracing for retaliation, US officials also appear to be operating under the assumption that China’s economic weakness—and uncertainty over the US election—will temper Beijing’s response. But just as the US is highlighting the dependencies that it wants to break with tariffs and other measures, it is also providing China with a target list for retaliation. In this note, we break down Biden’s big tariff move, look ahead at additional measures the US is readying to target China, and what this collectively means for Beijing’s potential response.

What we know

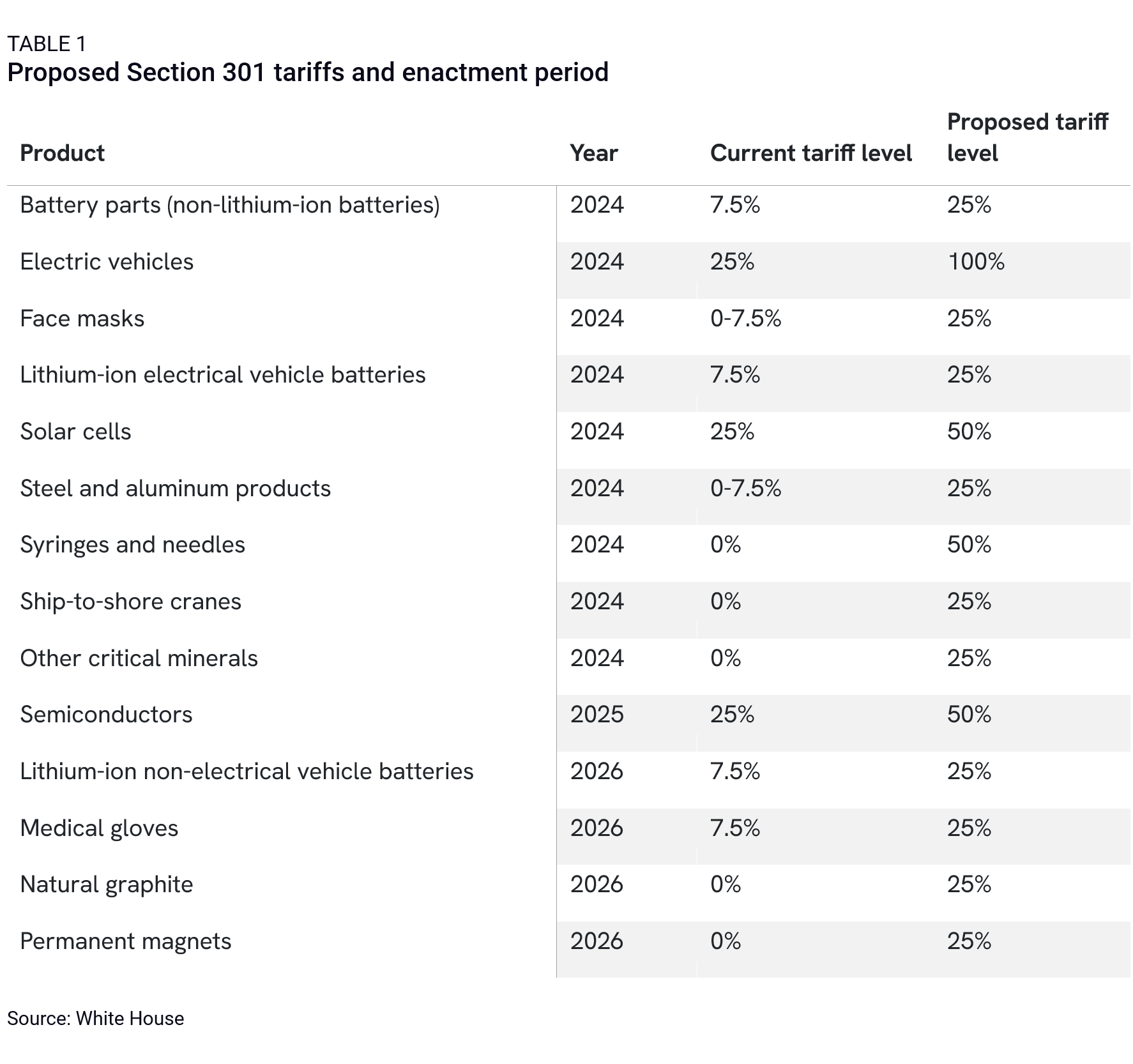

The long-awaited US Trade Representative (USTR) review of Trump-era Section 301 tariffs proposed tariff hikes on certain strategic goods imported from China. Most tariffs will go into effect sometime this year, with others phasing in in 2025 or 2026 to give importers adequate time to adapt. Tariffs for most of these goods will be raised to 25%, though some will see higher tariffs of 50%—semiconductors, solar cells, and syringes and needles—or 100% in the case of electric vehicles.

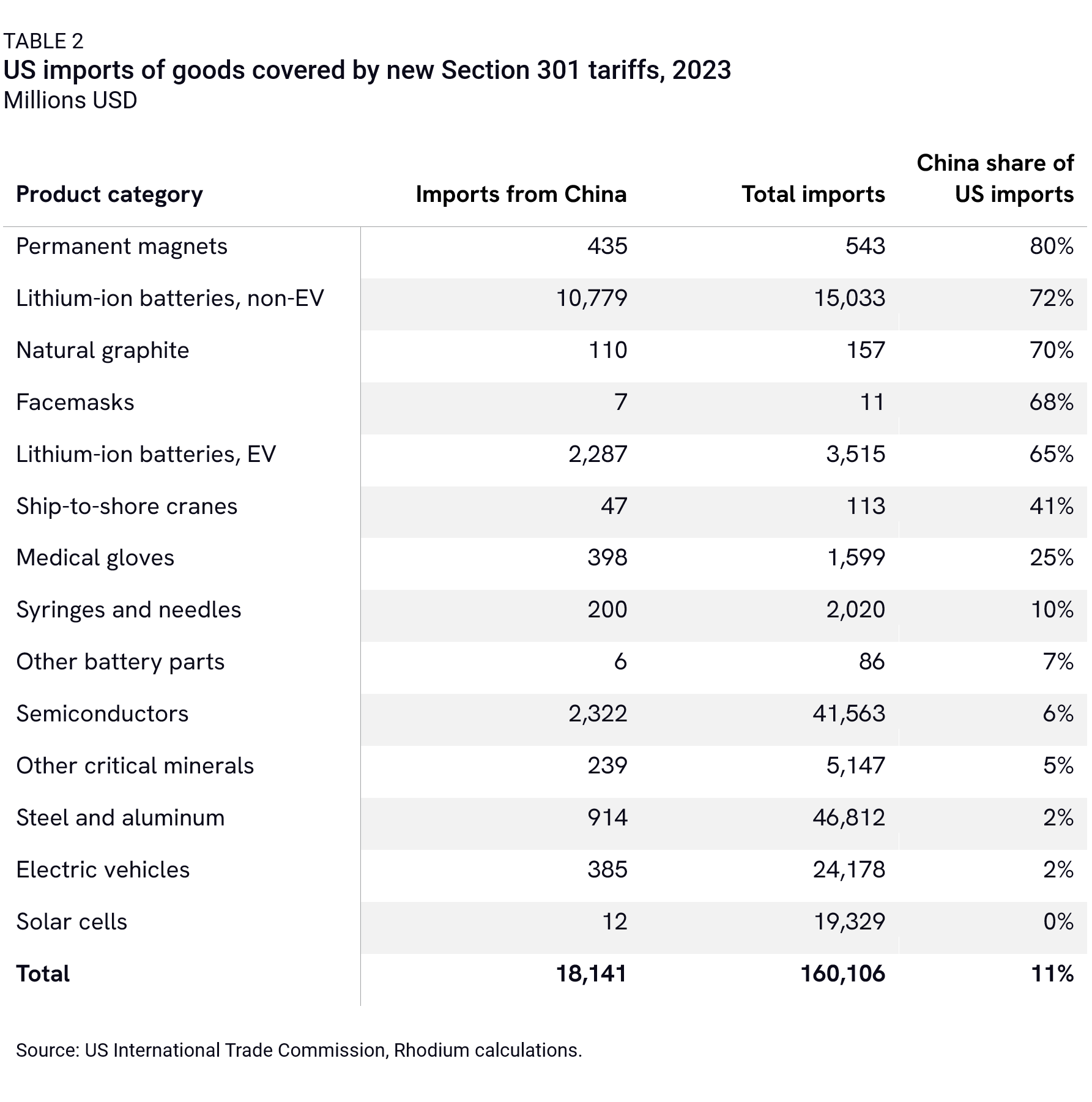

On May 22, USTR published the list of trade codes subject to increased tariffs. In 2023, the US imported $18.1 billion worth of these goods (see Figure 1). The largest product category is non-EV lithium-ion batteries ($10.8 billion, 59% of total), followed by semiconductors ($2.32 billion, 12.8% of total) and lithium-ion batteries for EVs ($2.29 billion, 12.6% of total).

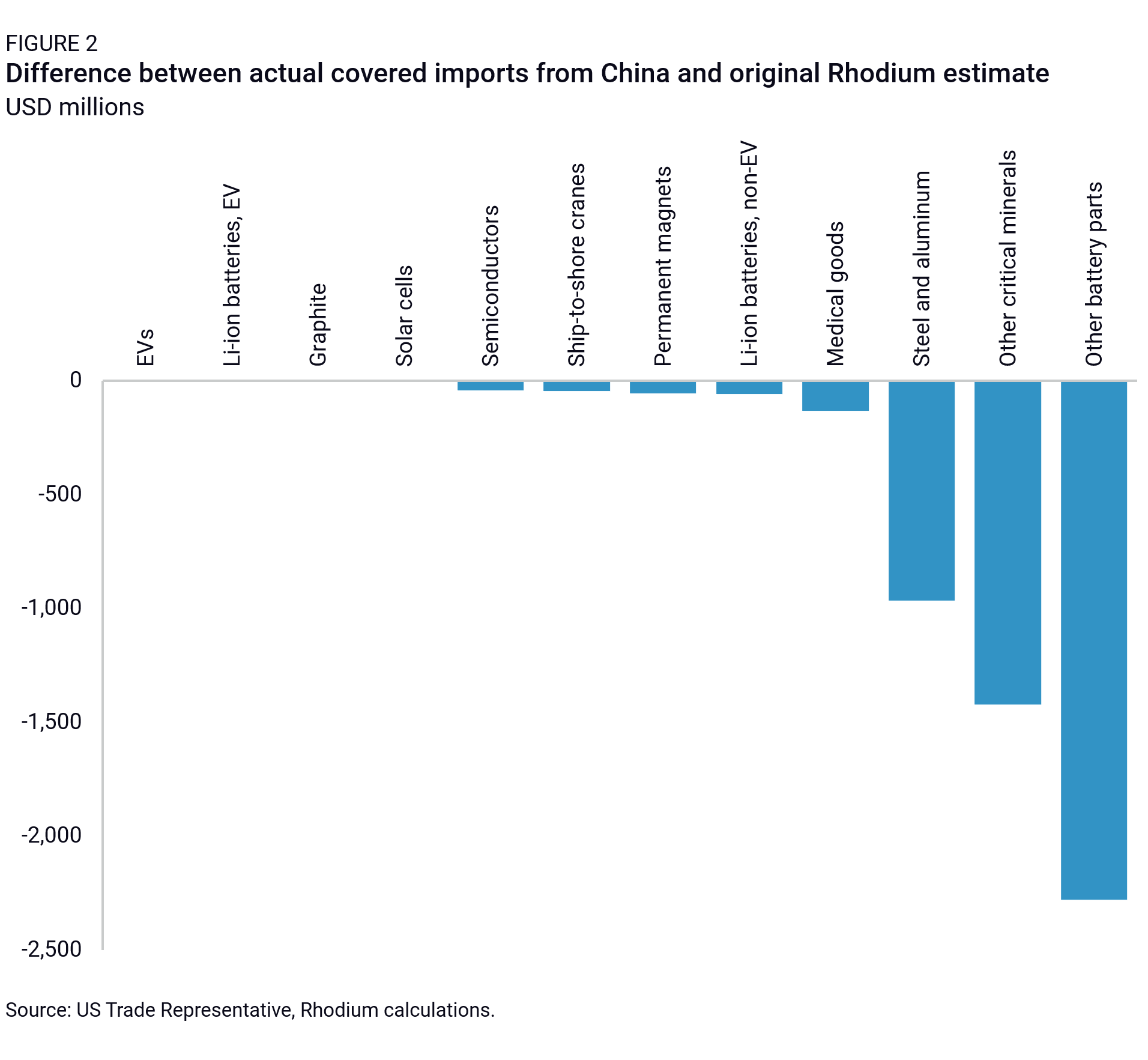

When the tariff announcement first came out, but before specific product codes were released, Rhodium Group produced an estimate of what might be covered based solely on the product descriptions in the Section 301 report. We estimated that around $23 billion worth of goods matched the descriptions of covered products. We knew this estimate was high based on the White House guidance that around only $18 billion of goods would be covered.

Figure 2 shows the difference between the actual volume of covered imports and our original estimate. For most product categories, we were right on the money or very close. The gap between our (broader) estimates and the actual coverage in the remaining categories can tell us what the administration and USTR decided to prioritize given the long list of products that they could have chosen to cover.

The biggest gaps were in steel and aluminum, critical minerals, and other battery parts. In steel and aluminum, we originally included all steel and aluminum products covered by existing Section 301 tariffs. In the actual new tariff list, a range of mostly aluminum consumer goods (such as aluminum foil, ladders, doors, and window fixtures) are excluded. Here, USTR has appeared to carve out products with no strategic value and where tariffs would have a substantial impact on consumer prices.

The list of “other critical minerals” in the new 301 tariffs is much shorter than we expected. In our original estimate, we included all critical minerals as categorized by the International Trade Administration’s Draft List of Critical Supply Chains, totaling 268 products and $1.7 billion in goods imported from China in 2023. The actual list covers only 26 products at the HS8 level, totaling $239 million of goods. The list excludes a number of archetypal critical minerals, such as the rare earth elements yttrium and scandium ($91 million imported in 2023), antimony ($102 million), germanium ($10.6 million), and gallium ($8.1 million).

The largest gap between our estimate and the announced tariff list was in other battery parts. Here the list is short. Our list included only two product categories: lead-acid battery parts ($6.4 million), and non-lead-acid battery parts ($2.28 billion). The USTR 301 list carved out non-lead-acid battery parts, leaving only $6.4 million in goods covered under this heading. Given that lead-acid batteries are a mature technology, the decision to carve out all other battery parts from the new tariff list appears to be an implicit recognition of US dependence on China for these components for the near future.

Using the HS codes provided by USTR, the categories where the US is currently most dependent on China in terms of import share are permanent magnets (80%), non-EV lithium-ion batteries (72%), and graphite (70%). Within each category, different products have different degrees of import dependence on China. In critical minerals, for instance, overall dependence is only 5%, but some products have a high share of Chinese imports, notably tungsten (65%), bauxite (56%), chromium (42%), and tantalum (34%).

There are several notable features to Biden’s targeted tariff list:

- Nipping EVs in the bud: The impact on EVs is relatively limited given that virtually no Chinese EV maker has begun directly exporting to the US (the exception is Geely-owned Volvo and Polestar, which has been taking advantage of the US Duty Drawback program, an old tax mitigation mechanism that allows US-based automakers to recoup import tariffs with certain exports). We expect cybersecurity restrictions to finish the job in barring China-made EVs in the US. Chinese EV companies going abroad, along with Chinese investment deals in US FTA partners like Mexico and South Korea, will be under tight US scrutiny for potential circumvention of US EV-related tariffs.

- Batteries in focus: The tariff emphasis on batteries and battery components layers on top of already stringent Inflation Reduction Act conditions for EV tax credit eligibility. The IRA conditions are designed to extricate China from EV supply chains in North America and have already spurred transactions between US companies and Korean and Japanese battery makers. Tariffs are meant to drive a further increase in battery manufacturing in US and partner countries. Notably, the 25% tariff on EV batteries makes it far less likely that US-based automakers forego IRA tax credits in exchange for cheaper Chinese EV batteries. In addition to EV batteries, the US is also targeting large batteries for energy storage, where China accounts for 71% of US imports. Given the greater dependency for energy storage batteries, the US is giving until 2026 for the tariffs to kick in. The battery tariffs will bite for China as well, given that the US is a major market for Chinese EV battery exports. The loss of the US market could lead to further price cuts and increased competition from Chinese battery exporters.

- Kicking the can on component tariffs: The US is trying to dissuade companies from sourcing cheaper mature-node semiconductors from China as Chinese foundries ramp up production capacity in response to US tech controls. An increase from 25% to 50% tariffs on semiconductors from China buys the US some time in this policy debate, but we expect further action on legacy chip restrictions. We’ll be watching Commerce in particular on whether it pursues Section 232 tariffs on components containing China-sourced chips (more on this below).

- The feedback loop: The US administration selected several targets for tariffs that have already been targeted by China in retaliation for US measures, including graphite, solar cells, and permanent magnets. The US can argue that since China has already demonstrated coercive leverage over these inputs, these are priorities for rapid diversification away from China. If China now tightens restrictions on its original retaliatory targets that the US is now targeting for tariffs, then the US can underscore the need for supply chain resilience while framing China’s measures as retribution.

- A very slippery slope: In taking a more targeted approach to tariffs, the US is spotlighting areas where it has critical dependencies on China that it is actively trying to reduce. But this also raises the bar for retaliation. For example, applying tariffs on face masks, syringes, and needles sends the signal that the US is ready to deploy its toolkit to reduce US healthcare dependencies on China. But China still holds significant leverage in areas like pharmaceutical inputs, ventilators, and lab equipment that could significantly impact the US healthcare system if China were to retaliate within the same sector. US officials may be gambling that Beijing won’t assume the reputational risk of targeting medical products in retribution. Then again, China has already shown a willingness to target clean tech inputs amid growing global concerns over climate change.

- Limited scope: Notably, the report did not attempt to revamp the scope of the original Section 301 investigation, which was centered on IP theft. Nor did it attempt to recalibrate the tariff list, to include a lowering of tariffs for more benign goods. The purpose of this review is more targeted: to signal to companies in strategic sectors marked for tariff increases that the clock is ticking to diversify, and to make clear to Chinese companies—and US trading partners—where the US market will effectively be off limits. Timing matters, though. Just as the US is showcasing its dependencies on China and ambitions to wean off them, China, too, is evaluating what those pain points are that can be struck in the near term.

How will Beijing retaliate?

In keeping with its diplomatic protocol to keep communication lines open amid escalation, US officials warned their counterparts in Beijing in advance that the new round of tariffs was coming. The White House appears to have assessed that some degree of Chinese retaliation is expected, but it will be restrained as China tries to avoid aggravating its own economic troubles. In particular, US officials are betting that China will avoid extreme or asymmetric moves for fear of accelerating investor flight and diversification from China.

China’s response to US tariffs will not be happening in isolation. China is also weighing its response to tightening US tech controls, impending EU duties on EV imports from China from an anti-subsidies probe, and intensifying G7-level discussions around data and cyber-related tools to restrict China. Moreover, EU elections in June and US elections in November will weigh on the timing and magnitude of China’s response. We see several options for China’s retaliation, not all of which are mutually exclusive.

Tit-for-tat tariffs: In our view, the most likely outcome is for China to respond with tit-for-tat tariffs on American exports. One version of this approach would be to reimpose tariffs on US products from the Trump trade war era on a basis that roughly matches the $18 billion in promised tariffs from the White House. The advantage of this approach would be its simplicity—China’s bureaucracy has already gone through the exercise of identifying imports from the US that they are comfortable targeting with 25% or greater tariffs.

The US exported $6.2 billion worth of automobiles to China in 2023. Given existing overcapacity in the Chinese auto sector, it would be easy for China to replicate the 100% tariffs on US auto exports without serious harm to its own consumers. China has already threatened retaliatory tariffs on US and EU autos in a statement made by the China Chamber of Commerce to the EU on May 21. Though Beijing may not deem it necessary, it could also re-impose tariffs on US agricultural products, potentially with an eye to affecting political outcomes in ag-heavy swing states like Ohio.

Export restrictions on US product exclusions and carveouts: China could target the very items that the US has identified for temporary tariff exclusions due to their heavy dependence on China. In fact, the USTR report (see Appendixes K and L of the report) lists manufacturing equipment for machinery and solar wafers for temporary exclusions, which China could in turn restrict to create pain for US-based firms and undermine US industrial policy efforts to excise China from clean tech supply chains. The carveouts within steel and aluminum products, critical minerals, and particularly battery parts are also likely targets.

Currency devaluation: Beijing may allow a limited depreciation of the yuan to blunt the impact of tariffs. The yuan is already facing depreciation pressure, and efforts by the PBOC to stabilize the yuan exchange rate at current levels have primarily benefited foreign investors speculating on the currency. All Beijing needs to do is step away from defending the yuan at current levels, allow a modest depreciation, and then step in again with intervention to establish a new baseline for the exchange rate.

We view this as a very plausible response, especially given ongoing pressures on the yuan more generally. However, it also poses risks for Beijing in its trading relations with other countries. A weaker yuan makes Chinese goods more accessible to markets putting up tariff barriers, but it would also undercut competing producers across the developing world. This could amplify growing concerns in these economies over China’s overcapacity problem.

Export controls on critical material inputs and technology: China already updated revisions to its export control catalog in December 2023 to cover solar wafer manufacturing technology (though it later backtracked), LiDAR systems, gene editing and synthetic biology technologies, crop hybridization, and bulk material and logistics technologies. China has also activated restrictions on some critical minerals—the US, the Netherlands, and Japan have faced gallium and germanium restrictions, but Beijing has been far less aggressive in restricting graphite. China could tighten export restrictions and expand its export control catalog to cover more critical inputs, albeit at the risk of accelerating diversification away from China.

M&A disruptions: Many breathed a sigh of relief when China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) approved a VMWare-Broadcom deal at the time of the APEC summit in November last year, but China still holds considerable leverage to disrupt strategic M&As, especially if those transactions are designed to diversify away from China. One key deal we’re watching is an attempt by US firm Synopsis, a leader in electronic design automation software, to acquire another US firm, Ansys, which specializes in auto engineering software. The pending $35 billion deal has an extended deadline until mid-2025, so there is still time for SAMR to drag out its review.

Selectively targeting MNCs: Unlike the Trump-era tariffs, which were largely focused on hitting a big number in the value of goods covered by tariffs that could then be used as leverage for ambitious deal-making with Beijing, the Biden tariffs take a more targeted approach. They signal which strategic sectors the US is actively working to reduce China dependency in. For example, Chinese EV makers can try eating the cost of 100% tariffs, but national security-based controls on ICT technologies may shut them out in the end anyway.

In this context, China may consider selectively targeting MNCs to deny their access to the Chinese market in retaliation for the US putting up a tariff wall. For example, while Tesla evidently is still valuable enough to Beijing to drive innovation in the Chinese market and earn full self-driving certification in China, a GM or Ford facing stiff Chinese competition could become a victim of consumer boycotts, investigations, or regulatory barriers that make it more difficult to operate in China. US firms that are relying on Chinese foundries for legacy chips could also see their contracts dropped if orders are given to reserve more production capacity for Chinese customers.

The risk Beijing runs with interfering with MNC operations is that it reinforces ongoing concerns among foreign business leaders that geopolitical headwinds are simply making it too hard to invest confidently in China. Local governments in Beijing have worked hard over recent months to incentivize foreign businesses to stay. Ritually sacrificing foreign businesses in retaliation to the new tariffs would undermine those efforts.

More to come?

While the USTR report did not formally expand the scope of the investigation beyond the original cause of IP theft, it did make multiple references to cyber threats, market distortions created by China’s production overcapacity, and the need to build supply chain resilience in critical segments. The target list reflects the creeping scope. Steel and aluminum tariffs are tied to level playing field concerns, ship-to-shore cranes are related to cybersecurity risks, and medical products are geared toward reducing sourcing of critical goods from China.

The list of theories of harm linked to China has also expanded considerably since the Trump administration. In addition to concerns over IP theft and market distortions created by Chinese excess production capacity, lack of data and cyber, environmental, and labor and human rights protections are all ripe for additional regulatory measures.

Here is what’s on our watch list:

- Additional Section 301 investigations: Less than a month before the recent Section 301 tariff announcement, the Biden administration launched a new Section 301 investigation into Chinese shipbuilding, maritime, and logistics. While stretching the scope of the Trump-era investigation on IP theft, the Biden administration appears to prefer launching more targeted investigations rather than the former Trump administration’s mode of creating an umbrella investigation to justify tariffs across the board.

- Section 232 tariffs and quotas: Commerce has a powerful tool to impose national security tariffs or quotas under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. While USTR raised tariffs on semiconductors, the impact is marginal given that US companies typically import assembled electronic parts containing mature-node semiconductors from China rather than the semiconductor itself. Commerce is studying the results of an industry survey now and may employ Section 232 tariffs or quotas to target components containing China-sourced chips (see May 7, “Thin Ice: US Pathways to Regulating China-Sourced Chips”).

- Commerce ICTS controls: The Commerce Department’s authorities under the Commerce ICTS rule to restrict information and communications technology and services are a swifter approach to phasing out China-sourced tech in strategic areas (see March 4, “Shut Out: Data Security and Cybersecurity in the Next Wave of US Tech Controls”). 100% tariffs on EVs, for example, buy US automakers some time and signal to Chinese EV firms and key US trading partners like Mexico and South Korea that Chinese EVs and parts will not be welcome in the US market. A pending ICTS investigation into connected vehicles could also effectively ban Chinese-made EVs from the US market.

- G7 discussions on ‘trustworthiness criteria’ for critical supply chains: The Biden administration’s readout of the Section 301 tariffs emphasized the importance of working with partners to address “China’s unfair practices—rather than undermining our alliances or applying indiscriminate 10% tariffs that raise prices on all imports from all countries, regardless whether they are engaged in unfair trade.” The Biden administration is clearly trying to differentiate itself from Trump’s more blunt approach of across-the-board tariffs while signaling intent to coordinate with like-minded partners on diversifying away from China in critical goods. US partners may be more wary of engaging in punitive measures on the same level as the US but will likely be open to affirmative trade actions in the name of supply chain resilience. After all, the EU Commission is already readying duties on China-made EVs and may soon launch its own cybersecurity investigation into connected vehicles to steer member states toward guardrails. We expect the concept of “trustworthiness” criteria among partners to be among the top discussion items at the upcoming G7 summit in mid-June in Italy.

Pick your poison?

The upcoming US election presents two comparably concerning outcomes for Beijing. On the one hand, an abrasive Trump administration with little regard for plurilateral coordination would rely heavily on blunt national security measures targeting China but would lower the chances of G7 convergence and could give China more room to maneuver with Europe. On the other hand, a second Biden term would mean a further ratcheting up of hard-hitting tech, trade, and investment controls and the potential for a stronger G7 coalition cornering China. There is no clear-cut preference for Beijing in this race. As a result, China may not put as much emphasis on trying to sway the US electorate through retaliatory tariffs.

For example, agricultural goods are an easy target for Beijing, as they have been in the past. But Chinese tariffs hitting trade in rural US states could end up boosting both Trump and Biden’s standing, cancelling out any intended political effect. This does not preclude China from exercising the option of tit-for-tat tariffs, but the motivation may have more to do with demonstrating to its own citizenry that China is not afraid to strike back against a perceived campaign to “contain” China’s economic development than to shape a particular political outcome in the US.

But there is a deeper concern that will likely weigh on Beijing beyond the current tariff spat. The Trump administration shone a light on China’s trade abuses to argue that their non-compliance with WTO rules meant that China should not benefit from the same trade privileges as other market economies. The Biden administration inherited that argument, dabbed a bit of diplomacy on it to get partners on board, and evolved the rulebook to systematically address multiple theories of harm concerning China. Meanwhile, policy proposals to revoke China’s Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR) status have gained momentum. The House Select Committee on China nuanced this proposal, suggesting a China-specific tariff column. The Biden administration is shying away from PNTR revocation, preferring instead to focus on a targeted list of strategic items for tariff hikes. But in effect, a China-specific tariff column is already developing and will likely have lasting effects in reorganizing global trade. A second Biden term could formalize this process, while a Trump administration trying to outdo Biden on tariffs may end up resorting to more extreme measures, like import bans on strategic goods and full blocking sanctions on Chinese firms. In either case, the second coming of the ‘Tariff Man’ points to a grim prophecy for US-China trade.