Car Trouble: ICTS Rule Rewires Global Auto Supply Chains

The US is forging ahead with new measures to bar Chinese-made vehicles as well as certain software and hardware from the US market. Global automakers and their suppliers will now have to restructure their supply chains to comply with the new rules.

The US is forging ahead with new measures to bar Chinese-made vehicles as well as certain software and hardware from the US market. Global automakers and their suppliers will now have to restructure their supply chains to comply with the new rules—all while under stress from regulatory uncertainty and price wars with Chinese competitors. The measures illustrate Washington’s strategic vision of carving out ex-China trade blocs for critical technologies and related infrastructure. Similar to US-led semiconductor controls, this entails preemptive and unilateral new standards that exclude China, stringent reporting requirements that force companies to comply, and relentless attempts to steer partner countries into alignment. Our key takeaways include:

- The OEMs most immediately impacted by the rules include Volvo, Ford, and GM. For Geely-owned Volvo, the rules could force either an exit from the US market or compel a more fundamental corporate restructuring. Ford and GM will likely need to stop exporting vehicles from China to the US.

- Chinese OEMs are effectively shut out of the US market by the new measures. This will lead to a scattering of Chinese investment from North America to more permissive markets as Chinese firms like BYD either abandon or scale back investment plans for Mexico.

- The Commerce Department was restrained in defining the technology scope of the new rule for this first stage, but we expect other parts of the supply chain—autonomous driving hardware, advanced semiconductors, and sensors like LiDAR—to eventually be covered. Commerce has meanwhile adopted expansive definitions of what constitutes ownership, control, and influence by the Chinese state, creating a chilling effect on transactions with Chinese auto suppliers.

- Part of the US strategic intent behind the new measures is to get auto OEMs over the hump of alt-China diversification. Once automakers have gone through the painful first step of overhauling their supply chains to serve the US market, Commerce will likely have collected substantial supply chain data to further refine restrictions. This information will theoretically give them more traction to steer alignment with G7+ partners.

- But to make an ex-China tech and trade bloc work, the US needs the EU on board. Washington and Brussels are already on a collision course over the role of industry standards to mitigate cybersecurity risks from China. German carmakers are placing big bets on China and the European Commission is using trade defense to draw in more Chinese investment, not block it outright.

- Geopolitical uncertainty over whether this transatlantic chasm can be bridged will determine the future shape of global auto supply chains. International OEMs, particularly in Germany, now face a critical decision: either purge Chinese suppliers from their global supply chains—creating an ex-China tech and trade bloc for connected vehicles—or leverage cost-effective and potentially more competitive Chinese technology for non-US markets. In either case, OEMs may increasingly ringfence their “in China for China” or “in the US for the US” operations.

Revving up

On September 25, the US Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) released a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) that would effectively shut out certain hardware and software that enable connectivity in vehicles, as well as the vehicles themselves, from the US market. The proposed measures follow seven months of investigation, including a public comment period and multiple working sessions with industry players. A final rule is likely before year-end.

The Commerce ICTS rule was born during the final days of the Trump administration and was then seized by the Biden administration to identify critical infrastructure areas where supply of information and communication technology and services (ICTS) from foreign adversaries might pose a national security threat. As we noted when the investigation was announced back in March (see “Shut Out: Data Security and Cybersecurity Converge in Next Wave of US Tech Controls”), Commerce’s tools and premise for the probe were likely to lead to far-reaching restrictions that would reshape auto supply chains. Commerce’s expansive authorities under the ICTS rule, combined with emerging data security rules, offer the most direct approach to shutting out Chinese firms in sensitive technology areas. Commerce was also driven to preemptively devise these rules for connected vehicles, given the costly (and ongoing) rip and replace measures for Chinese 5G telecom gear.

Connected vehicles were an obvious target for the new ICTS office at Commerce. First, they combine data security concerns (data collected on drivers, occupants, and nearby surroundings) with cybersecurity concerns (technical ability to remotely access the vehicle to exfiltrate data or sabotage the vehicle or connected infrastructure to create disruptions in geopolitical crisis scenarios). Second, the bleeding edge of the industry—autonomous vehicles—triggers regulatory anxieties over military end-use applications.

The US also fears Chinese EV competition will crush domestic auto firms, leading to efforts to shut them out—first a 102.5% tariff and then blunter ICTS controls. Washington is also contemplating how to accelerate diversification away from China in sensitive industries. By asserting that China’s political system enables the state to coerce private companies to serve its objectives, the US can use the ICTS rule to make a Chinese company anywhere in the world—or even an MNC with operations in China—a supply chain liability in one fell swoop.

Tightened steering

Commerce applied a relatively narrow technology scope to the proposed measures. Rather than stretching the national security argument to cover all components and connected systems, it filtered the target list by focusing on two questions:

- What technology transmits data into and from the vehicle?

- What technology enables remote control manipulation?

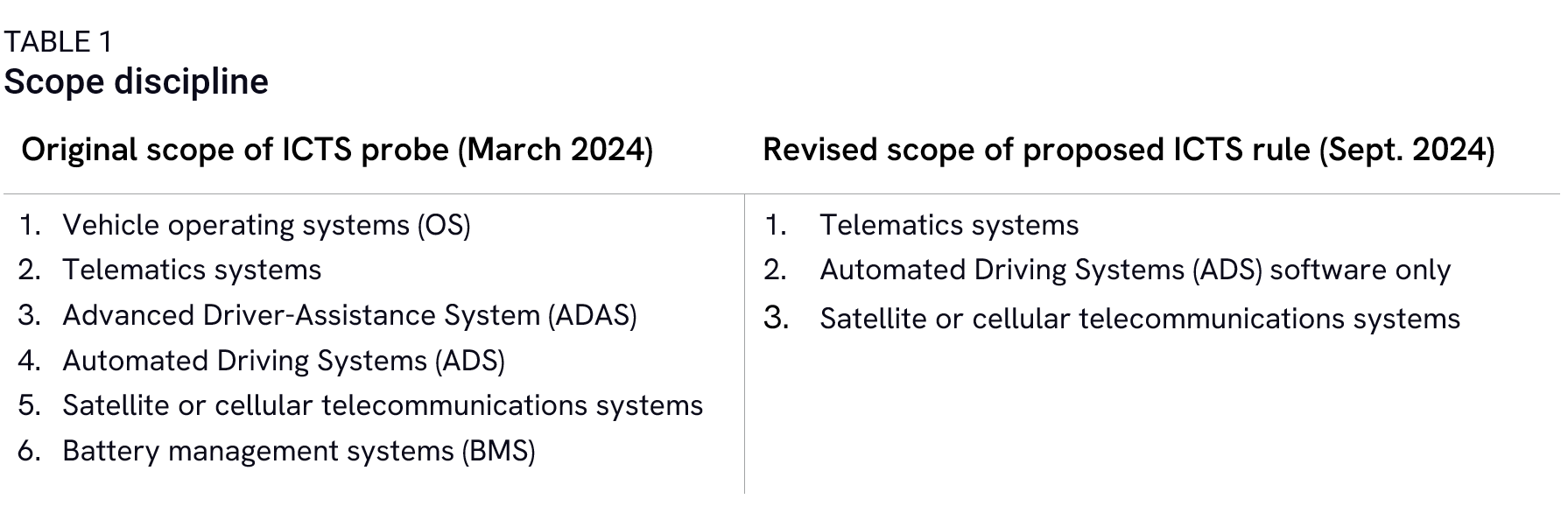

As a result, Commerce focused on the key control units and data transmitters in the car that drive telematics, navigation, and communication (Table 1).

With this narrower scope, Commerce focused the ICTS restrictions on two main areas for connected vehicles:

- Vehicle Connected Systems (VCS), covering both hardware and software that enable external connectivity.

- Automated Driving Systems (ADS), covering software only for highly automated driving (L3 and above).

Commerce also applied a “radio frequency above 450 megahertz” threshold to capture high connectivity and transmission functions across VCS and ADS systems. Low transmission functions like tire pressure monitoring systems and keyless entry were deemed to be low risk relative to consumer benefit, so hardware and software that enable those functions are not covered by the rule.

For ADS, Commerce is applying preemptive controls by concentrating on leading edge technology of L3 and above driving. Most vehicles on the road today are L2 and below, meaning the driver is still playing a dominant role, while L3+ technology is mainly deployed in testing pilots in China and the US.

Notably, the ADS prohibition is limited to software for now, as Commerce assessed that covering ADAS/ADS hardware would be too disruptive to auto supply chains at this stage. ADS hardware includes LiDAR systems, distributed electronic control units, ultrasonic sensors, advanced cameras, and high-performance GPUs. Commerce reveals the cost/benefit analysis it performed in scoping the measures: “a rule that coherently and feasibly addresses these varied supply chains would have disproportionate economic and supply chain impacts relative to the reduction of national security risks.”

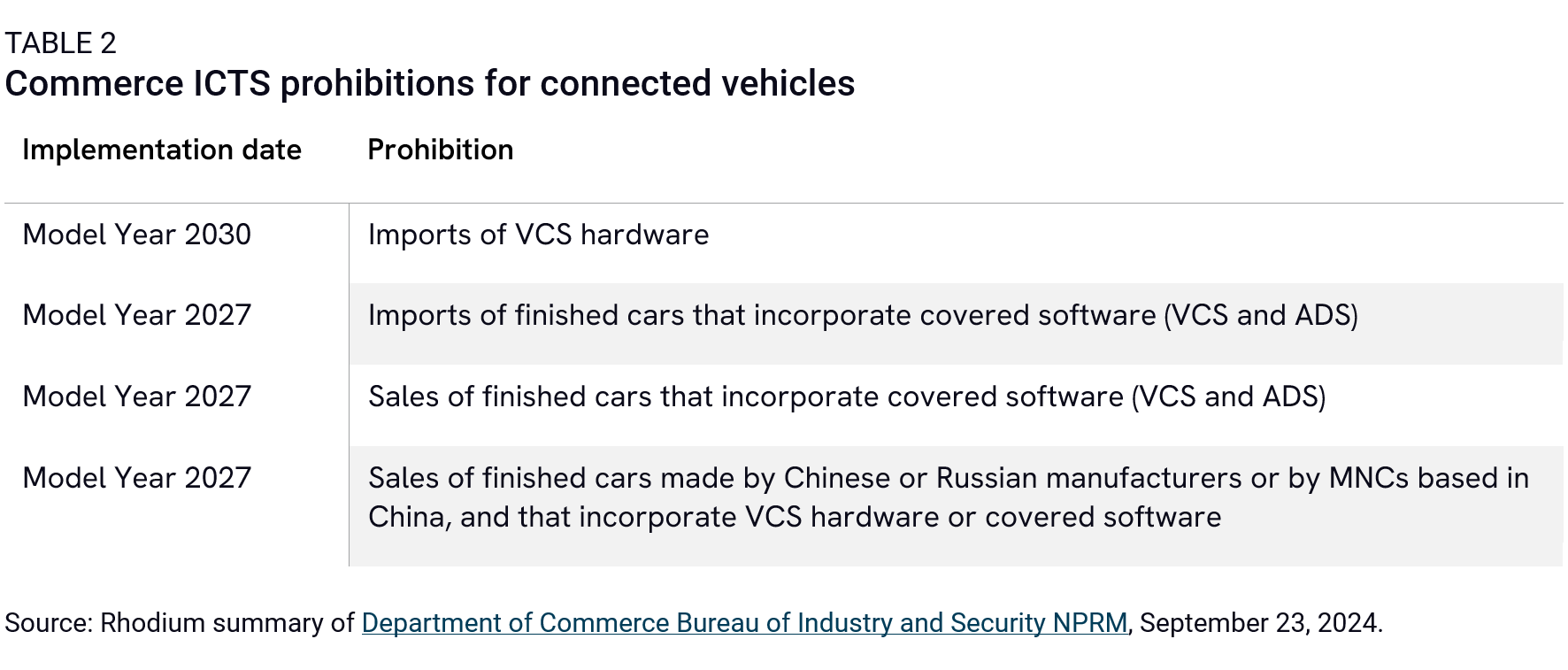

But the overall tone of the rule is “one step at a time.” Even as ADS hardware has fallen out of scope at this stage, LiDAR, ECUs, advanced cameras and sensors, and GPUs are obvious targets and we would expect more restrictions covering these areas to come down the line (Table 2).

Long range

While Commerce was disciplined in applying a narrow technology scope to the rule, it was expansive in defining the entities it covers. With the new measures, OEMs and their suppliers must audit their supply chains for VCS hardware and covered software to screen for persons “owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of a foreign adversary” (in this case, China or Russia).

The definition of persons subject to foreign adversary influence is expansive. For example, it covers:

- Any person, wherever located, who acts on behalf of the Chinese or Russian state, including if that person is “indirectly” supervised, financed, or partly subsidizedby the state.

- Any person, wherever located, who is a citizen or resident of a foreign adversary, or a country controlled by a foreign adversary, but not a US citizen or permanent resident.

- Any company or organization with a principal place of business in, headquartered in, incorporated in, or otherwise organized under the laws of a foreign adversary or a country controlled by a foreign adversary.

- This provision would implicate MNCs with subsidiaries in China, meaning any covered hardware or software developed or manufactured in China cannot be incorporated into vehicles destined for the US market.

- Any company or organization, wherever organized or doing business, that is owned or controlled by a foreign adversary.

- Owned or controlled is defined as any person that possesses direct or indirect power through a majority or a dominant minority share, board representation, proxy voting, special share, contractual arrangement, or other formal or informal arrangements that determine, direct, or decide important matters affecting an entity. This is an expansive definition that is likely designed to have a chilling effect on transactions with Chinese suppliers given the inherent difficulty in determining whether a Chinese firm is under the indirect influence of the state.

Running diagnostics

The proposed rule contains striking features that would make Commerce BIS the de facto regulator for connected vehicle supply chains. Similar to Commerce’s semiconductor playbook, the combination of stringent licensing and reporting requirements are designed to give Commerce extraordinary access to supply chain information. That information could then be used to further refine restrictions to both mitigate spillovers and accelerate auto diversification away from China.

With the new rule, OEMs and suppliers importing into or selling in the US market will be required to regularly submit information to BIS to verify supply chain compliance with US requirements or else face hefty fines. According to the rule, VCS hardware importers and connected vehicle manufacturers must submit annual “Declarations of Conformity” to BIS verifying that they have not engaged in a prohibited transaction and provide bills of material on hardware and software for connected vehicles, along with data on imports, sales, and suppliers.

Commerce creates an important hook for companies with the introduction of “specific authorizations.” Commerce is likely anticipating that many companies will face unique circumstances that may make it difficult to comply with the rules in the required time frame, especially for vehicle platforms that are already in development. Commerce is effectively opening the door to consultation with companies, implying that some flexibility could be negotiated so long as companies who want to preserve a foothold in the US market are taking substantive steps to unwind their supply chains with China.

Head on collision

The US ICTS measures will have the biggest impacts on Chinese OEMs (Volvo, BYD USA), Chinese suppliers of VCS hardware and covered software, the international MNCs that source from them, and the very few MNCs (GM, Ford) that are still exporting cars from China to the US.

Whiplash for Chinese carmakers

While steep US tariffs on Chinese vehicles deterred Chinese OEMs’ North American expansion, the ICTS measures effectively ban them from the US market. This was the outcome we forecast in March when the ICTS investigation was announced. Most Chinese OEMs do not export to the US, so this mainly affects their future expansion now that they have been denied the world’s second-largest auto market.

However, there are a couple high-profile OEMs that face more acute disruptions in the US market. Take Volvo, a company that is Swedish-branded yet Chinese-owned via Geely. In 2023, the company sold nearly 130,000 vehicles in the US, which made up 18% of the firm’s global sales. Since 2018, the carmaker has been producing vehicles for the North American market in South Carolina. In 2021, Volvo upgraded its plant to build EVs under the Polestar brand and has retail showrooms throughout the US. But under the current rules, the company will not be able to sell its vehicles in the US starting in 2027.

This is where the special authorization process will be particularly revealing. US policymakers don’t want to lose the jobs associated with Volvo’s US footprint, nor do they want to deny Americans—who are more likely to associate Volvo with its Swedish branding than its Chinese ownership—a popular consumer choice.

If the ICTS rule makes it untenable for Volvo to continue operating under Geely ownership, and if the firm faces a dire prospect of losing 18% of its global sales, then we expect intense boardroom dynamics ahead as the firm negotiates a special authorization with Commerce and debates whether its corporate structure is fit for the geopolitical times.

BYD is another case study. The Chinese auto giant established a manufacturing plant in Lancaster, California in 2013 with a focus on municipal contracts for electric buses as an entry point to the US market. But in December 2019, the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act barred companies from non-market economies from federal funding starting December 20, 2021. US regulators may grant special authorizations to help cash-strapped US municipalities transition away from BYD. Meanwhile, US and partner competitors in the e-bus market could see a growth opportunity if their biggest Chinese competitor is being phased out of the US market and may have to divest its US assets.

Chinese OEMs also face hard decisions on their plans for overseas expansion. With the exception of Geely, most Chinese OEM sales and nearly all production are based in China. However, this dynamic is rapidly evolving and Chinese carmakers are increasing their overseas investments (see “Pole Position: Chinese EV Investments Boom Amid Growing Political Backlash” and our China Cross-Border Monitor data on automotive investments) to be closer to consumers and circumvent tariffs. The ICTS rule is designed to capture Chinese companies in covered hardware and software no matter where they are in the world. In effect, this means that Chinese OEMs and co-traveling high-tech suppliers would not be able to use currently operational plants in Thailand or potential future plants in Mexico, Europe, or other parts of the world to supply the US market.

Will BYD follow through with plans to make a big ticket investment in Mexico with the US market now closed off? While BYD has reiterated that the potential Mexico plant would only supply the local market, they might be deterred by Mexico adopting similar rules in the lead-up to the USMCA renewal.

Some Chinese firms could try to adopt novel corporate structures to create distinct entities outside Chinese control to access the US market. However, the expansive definition in the ICTS rule over what constitutes indirect state influence over an entity means any such move to circumvent the rule would come with substantial risks.

Sharp turn ahead for international OEMs

MNCs that are still exporting cars from China to the US despite tariffs (27.5% on ICEs and 102.5% on EVs) are at most immediate risk. But this is a small grouping that only covers GM and Ford, which export Buick Envision and Lincoln Nautilus models, respectively, from China to the US. These exports made up 1.7% of GM and Ford’s respective US auto sales in 2024. From 2027, these cars would not be able to be imported or sold into the US unless the firms get special authorization.

The other major US OEM, Tesla, will be less impacted despite its significant footprint in China. The firm is already following a model of bifurcated supply chains. Tesla’s production for the Chinese and third markets is highly localized, with around 95% of components sourced locally—including from MNC suppliers in China. While Tesla has not—and now will not—sell Shanghai-made vehicles to the US, the carmaker will continue to export them to the rest of the world so long as markets remain open to vehicles with Chinese content.

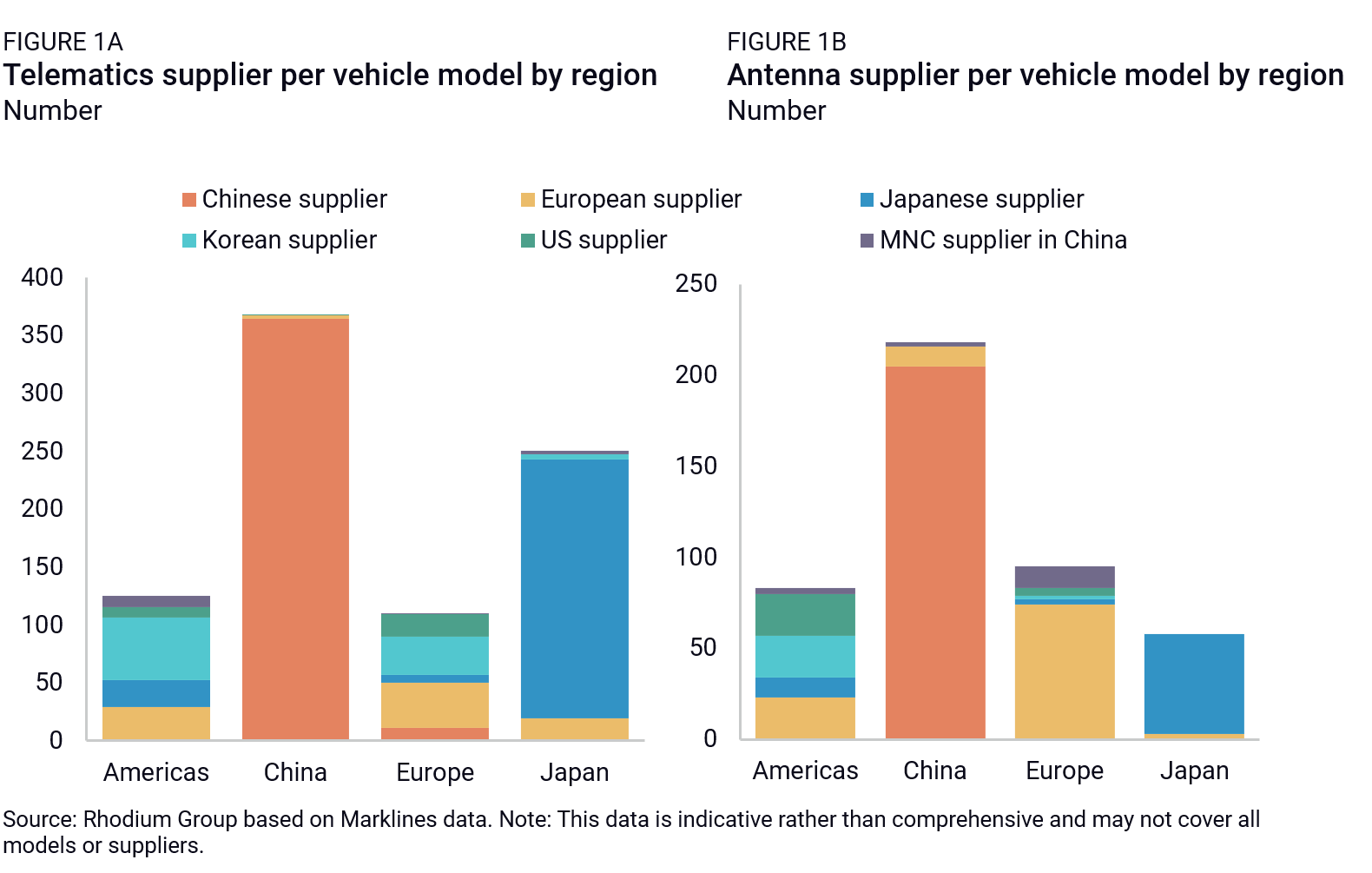

While US-based OEMs have a very low exposure to Chinese telematics control units and automotive antenna suppliers (Figure 1), there are several catches. First, several international telematics suppliers, such as LG, Marelli, and Continental, produce in China for international markets, including the US, and would be affected by the ICTS measures. Second, even when international suppliers produce outside China, they are likely to have China-based or Chinese suppliers in their supply chain. For instance, Chinese-owned Quectel (already under regulatory scrutiny in Congress) is a major supplier of network access device modules to international Tier 1 suppliers. Many upstream supply chains in microcontroller units, printer circuit boards, and WiFi modules are also likely to have China linkages.

Fork in the road?

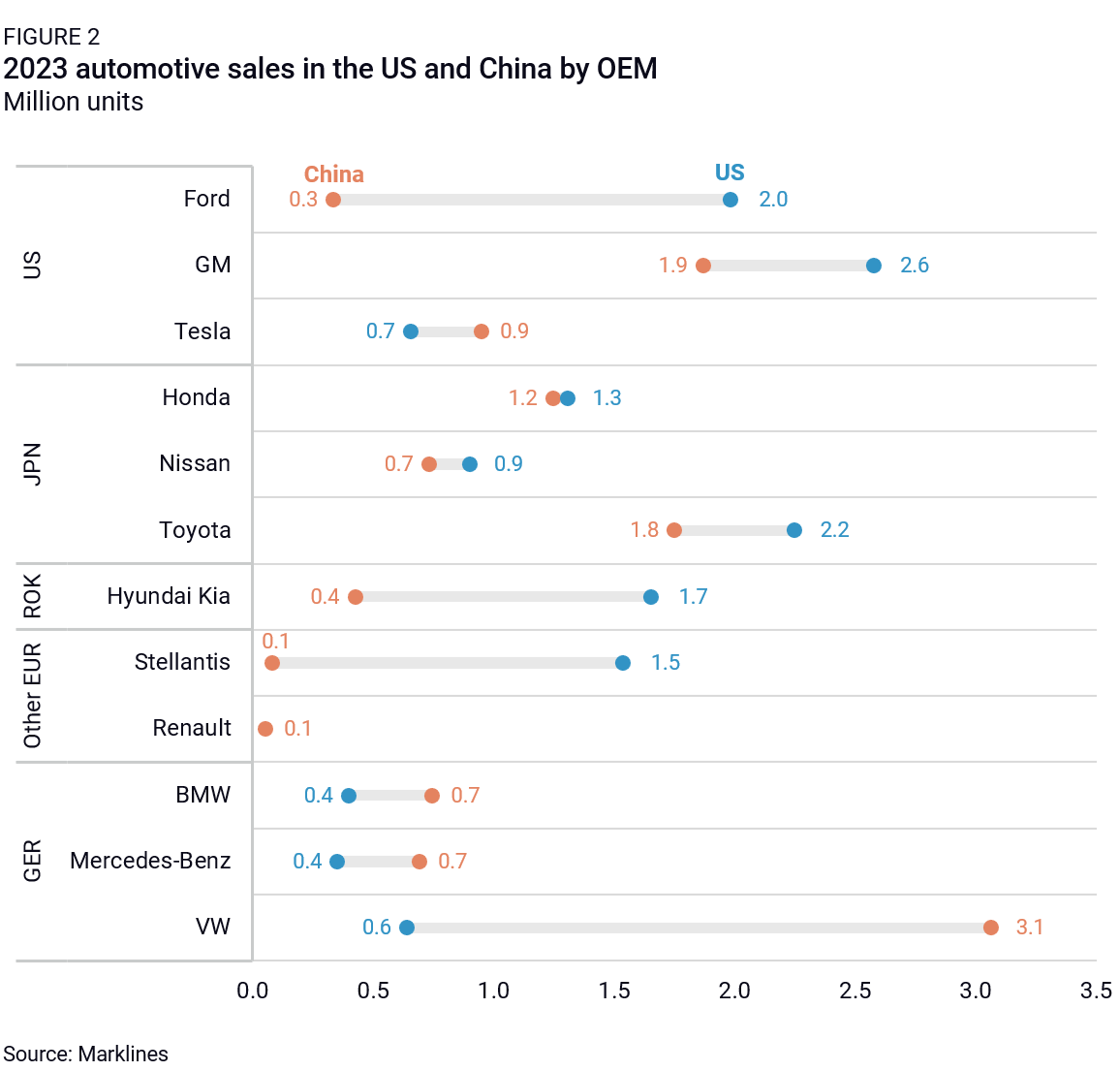

Companies that want to preserve US market share will have to revamp their supply chains for the US (and North American) market. For many firms calculating economies of scale, there could be a commercial logic to making supply chains ICTS-compliant in Europe and Japan, if not globally. This is particularly the case for US OEMs like Ford, GM, and Stellantis and Japanese OEMs that do a considerable portion of their global business in the US market (Figure 2).

That commercial logic does not easily translate to most German carmakers, however. Indeed, VW Group is the biggest outlier with sales favoring the China market over the US market by a wide margin. The German carmaker’s calculus of “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” in partnering with Chinese firms collides directly with a US political calculus of carving out ex-China trade and tech blocs for connected vehicles.

German carmakers that have run against the US’s regulatory tide and deepened partnerships in China are calculating that lower-cost and technologically competent Chinese firms will enable a smoother transition from ICE to EV fleet production. German carmakers may assess that they’re simply in too deep in China and need to follow a bifurcated supply chain strategy between North America and China plus the rest of the world.

VW is also an important case study for the ICTS software restrictions. The timeline Commerce chose to phase in restrictions (2029 for hardware and 2027 for covered software) was informed in part by its assessment of industry feedback that OEM software incorporation from Chinese suppliers is limited while hardware restrictions are likely to be more cumbersome and require more time for automakers to adapt. Tier 1 Chinese software developers for connected vehicle systems (i.e., Alibaba’s high precision maps, Baidu Apollo’s autonomous driving platform, and Huawei intelligent automotive driving systems) are geared toward Chinese OEM adoption, while international OEMs are more likely to rely on western Tier 1 system supplier like Bosch, Continental, and Aptiv.

But VW’s software company, CARIAD, has also been placing bets on China. CARIAD established a China subsidiary in April 2022 with a mission of “In China for China, from China to the world.” The company describes a two-step plan to develop software for the China market and jointly develop across Europe and China teams a software stack for global deployment of L3+ autonomous driving. The US ICTS rule throws a wrench into the second prong of that plan. VW, which has already been targeted by the US over forced labor components from China, continues to be a cautionary tale of the risks involved in trying to buck the US de-risking agenda.

Under the hood of US strategy

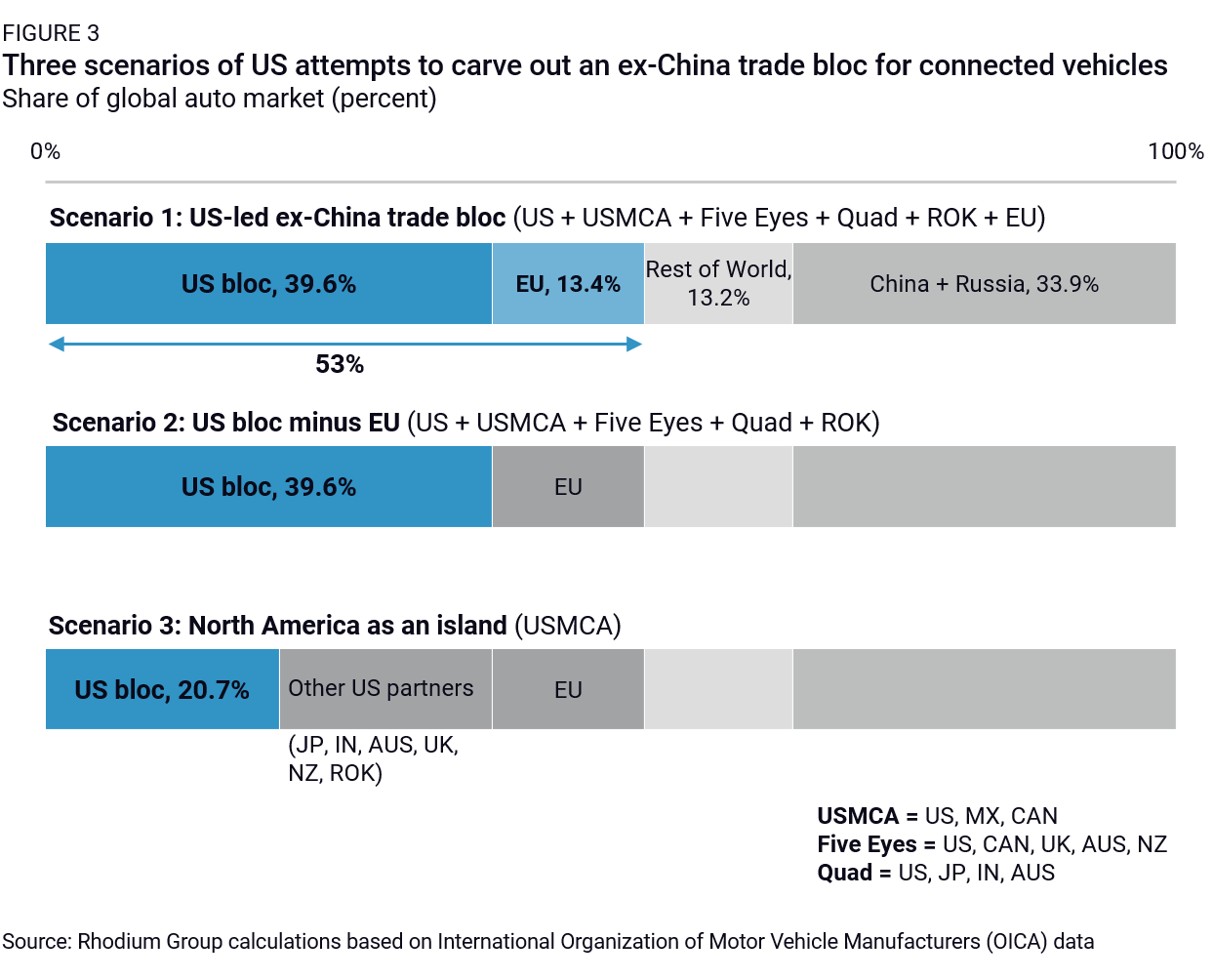

China has long used its vast market access to compel companies to adapt to its regulatory and localization requirements, and now the US is following a similar playbook. With new ICTS restrictions on connected vehicles, the US is forcing global auto firms and their suppliers to restructure their supply chains and question their position in China. This is a big bet given China’s pervasiveness and competitiveness in the auto sector (Figure 3).

We can infer that part of the US intent for the new ICTS rule is to get auto OEMs over the hump of alt-China diversification. In other words, step one of the US strategy is to force companies to undergo a painful process in the near term—purging Chinese firms from their supply chains and unwinding partnerships forged under the assumption that technologies developed in China could be deployed to the US market.

The next step is for the US to use the Declarations of Conformity to collect critical data on connected vehicle supply chains and selectively award companies with special authorizations so long as they show progress toward diversifying away from China. The third step (we would assume) is to phase in more restrictions (for instance on ADS hardware) with industry input and eventually implement trusted trade programs that exclude China.

By that point, OEMs and Tier 1s will have already gone through the painful first step of overhauling their VCS supply chains for the US market, in theory making it easier to nudge tighter alignment with the US. But a fundamental chasm between the EU and the US is already developing, starting with the role of cybersecurity industry standards.

The standards debate

Commerce is quite blunt in declaring that voluntary industry standards, which have long governed the automotive industry, do not meet US requirements for mitigating national security threats from China and Russia. The US argues in the rule that the Chinese and Russian governments have designed their political and legal systems to endow the state with “privileged access” to private firms, and that this access can lead to data exfiltration, tampering, and remote access and manipulation of connected vehicles.

This is quite unnerving for the EU, which is still trying to sort out its relationship with Chinese EV makers and would assert that industry standards play a vital role in mitigating cybersecurity risks from any actor—not just China. In contrast to the US’s blunt approach of banning Chinese EVs and suppliers, the EU would rather focus on trade defense like tariffs that draw Chinese EV-related investment into Europe with conditions (see “Terms and Conditions Apply: Regulating Chinese EV Manufacturing Investment in Europe”). Economic security from a European policy perspective could mean leveling the playing field with Chinese automakers as well as insulating the politically sensitive auto industry from costly regulations—especially national security regulations designed in the US that run the risk of triggering costly trade retaliation from China.

With the ICTS restrictions approaching, the US leveraged its convening power to bring together a group of like-minded countries on July 31 and brief them on the US’s risk assessment of Chinese connected vehicles and parts. These countries are now expected to come back to the US with their own risk assessments and mitigation plans. The EU plans to start work on a risk assessment into connected vehicles under its NIS-2 cybersecurity directive in October, with findings expected in March 2025. A 5G toolbox approach, in which member states ultimately decide on restrictions to varying degrees, is ill fit for connected vehicles moving across borders in the Schengen system. And with the US already declaring that standards are insufficient to address China-specific cybersecurity risks, Washington is raising the bar for the EU’s own risk mitigation plan.

Blind spot detection

With the ICTS rule in motion, global auto markets will look very different five years from now. A tangle of interconnected possible scenarios will determine the layout of that map:

Is the US or China the island? International OEMs will be forced to restructure supply chains to become ICTS compliant for the US market. They will likely also be operating under the assumption that the ICTS scope will expand over time (especially for hardware) and that other US measures (like outbound investment screening for AI-related systems) could also create entanglements abroad.

Other G7 countries could move in a similar direction over the next decade, creating more diversification momentum away from China. Amid this diversification drive, international OEMs could still attempt to ringfence their “in China for China” operations, but China would increasingly become an island for automotive manufacturing and Chinese OEMs would struggle to expand in advanced economies.

On the other hand, supply chains could mold around “in US for US” operations while China remains open to the rest of the world. A US strategy of cultivating ex-China tech and trade blocs for connected vehicles only works if partners buy into it. If they don’t, OEMs with “in China for China” supply chains and ICTS-compliant ex-China operations would face off against OEMs that leverage cheaper and potentially more competitive Chinese technology—given the size, dynamism, and level of state support in China—in third markets like Europe or South America. In an optimal scenario for the US, Washington wins over partners in creating a trade and tech bloc for connected vehicles and some 53% of global market share would be blocked off from Chinese competition. In a worst-case scenario for the US, where Washington is only able to assert restrictions with its North American neighbors, Chinese and international OEMs with Chinese technology would only be blocked from 21% of global market share. See Figure 3 for our scenarios.

Europe as the swing vote: The economics of an ex-China trade bloc for connected vehicles only makes sense if Europe is on board. The European response to US arguments on cybersecurity industry standards or BIS reporting requirements is key. With German carmakers most deeply impacted and the specter of VW factories in Germany top of mind, the European Commission could assert a stronger “economic security” line that prioritizes damage control for the auto industry in Europe. With backing from member states that are less exposed to China on autos but feeling the brunt of Chinese retaliation, Brussels could push back against Germany and drift closer to a US vision of a G7 trusted trade bloc for connected vehicles. The Commission forging ahead with EV duties despite stiff German resistance is already a big clue, but on national security matters the Commission will have to rely more on buy-in from big member states like Germany. Additionally, transatlantic fissures and regulatory uncertainty under a Trump 2.0 scenario could short circuit G7 convergence and lead to a deeper fracturing of global auto supply chains.

Scattering of Chinese investment: Chinese suppliers already integrated with the North American market face a choice: try to focus on producing parts and software not covered in the rules to keep a foothold in the US, or forego the US market altogether and focus on building out their footprint in a less hostile market. This could create an exodus of Chinese EV-related firms in the North American market. Firms like BYD or Luxshare might, for example, pivot away from Mexico. And if BYD redirects those investments to markets that are still open to Chinese OEMs, like Europe, it could trigger tightening of FDI conditions by host countries.

China’s retaliatory response: The prospect of US-led measures accelerating ex-China diversification and stunting China’s growth in global EV markets comes as China is already bracing for EU duties on China-made vehicles. At a minimum, we expect these measures to accelerate China’s self-sufficiency drive for key automotive technologies like autonomous driving chips as well as the hardware and software solutions highlighted in the ICTS rule. International MNCs already localizing to be considered a trusted Chinese supplier may face more stringent requirements ahead if China adopts the US’s expansive definition of what constitutes ownership, control, and influence over a China-based subsidiary.

But will China also act on retaliatory threats to target legacy automakers that are already struggling in the Chinese market? Or will China restrain itself out of fear that such moves will only accelerate diversification, sticking instead to selective trade restrictions on critical inputs for clean tech supply chains? And if more companies try to shift from sourcing products from China toward licensing IP from China so that they can manufacture covered products themselves, will China grow more assertive in restricting exports of its technology and know-how?

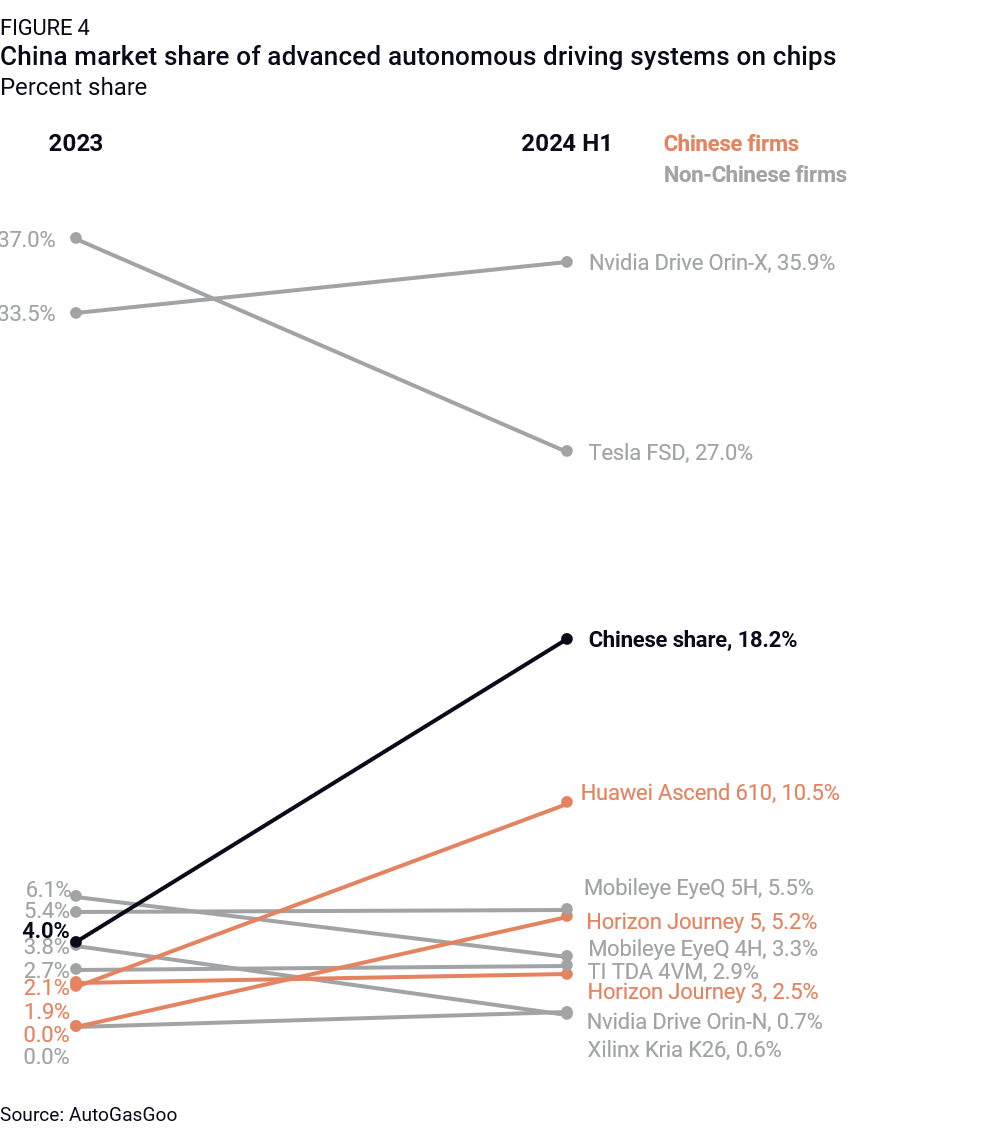

Decoupling autonomous driving? The ICTS rule carves out L3+ driving technology as a leading-edge space with dual-use applications that the US wants to preemptively decouple from China. Even though ADS hardware is excluded for now, we expect products like autonomous driving chips and LiDAR systems to eventually fall in scope. These are areas where Chinese firms have been making headway in their home market even as foreign firms remain dominant for now (Figure 4). In addition to ICTS measures, outbound investment screening and BIS entity listings could also be deployed to regulate US development of AV technology in China and target Chinese companies in this space. And with Chinese autonomous driving companies like Pony.ai likely losing access to the US market as a result of the ICTS rule, US companies trying to leverage the Chinese market to develop AV technology could also face more significant regulatory barriers ahead. Tesla has made initial progress in winning Beijing’s regulatory approval to deploy its “Full Self Driving” systems in China, but it could become collateral damage in the wake of the ICTS measures.

How will MNCs manage a mounting compliance burden? The ICTS rule is written so Chinese companies would not be able to simply relocate to Mexico or Vietnam to escape scrutiny of connected vehicles and parts coming into the US. Moreover, the expansive definition of entities “owned or controlled by” the Chinese state, including informal arrangements that confer indirect influence, will have a chilling effect on transactions with Chinese suppliers.

A recent Senate Finance Committee investigation already reveals significant doubts over auto firms’ due diligence efforts in China. That investigation into auto parts made with Uyghur forced labor resulted in a holdup of vehicle imports at the US border. It concluded that questionnaires, self-reporting, and audits of direct suppliers are insufficient to proactively identify forced labor exposure in supply chains. The ICTS rule is focused on a different theory of harm, but the concern remains that auto companies will be unable to sufficiently audit Chinese suppliers to determine whether they are under “indirect influence” by the state. While MNC compliance teams have their work cut out for them to audit supply chains, executive boards and strategy teams will also need to invest in rigorous scenario planning to inform their next move. The stakes are high. The decisions OEMs make as they grapple with the new ICTS rule and questions over geopolitical alignment over the next five years will dramatically reshape global auto supply chains for decades to come.