China’s Harsh Fiscal Winter

China’s aggregate fiscal revenues are likely to decline in 2025, even if China meets its full-year economic growth targets of “around 5%.”

China’s fiscal constraints will become a central issue for Beijing as fiscal revenue growth has flatlined for several years, and will likely decline outright in the future in the absence of structural fiscal reforms. Rising fiscal deficits will force trade-offs in domestic spending priorities, and will reduce the scope for additional stimulus. Central bank purchases of government bonds will become increasingly necessary to keep government and corporate debt burdens sustainable without raising interest rates. Tax reforms are urgently needed—yesterday.

Buried within the voluminous releases of the reports from the “two sessions” earlier this month was an astonishing data point: China’s anticipated full-year fiscal revenue growth in 2025 was only 0.1% compared to 2024, including both national tax and non-tax revenues. In other words, even if China’s economy grows at the targeted level of “around 5%,” the Ministry of Finance is officially anticipating that total general fiscal revenue would remain at the same levels as last year and basically unchanged from 2023 levels as well.

In 2024, the Ministry of Finance targeted 3.3% revenue growth, and did not even reach that: tax revenues declined outright by 3.4% and only a 25.4% surge in non-tax revenues prevented an outright decline in fiscal revenue growth. Land sales revenues collected by local governments—the other major source of non-tax revenue in China’s fiscal system—declined by 16% to 4.9 trillion yuan, down 44% from peak annual levels in 2021 because of the dramatic adjustment in China’s property sector.

Outright declines in fiscal revenue ahead

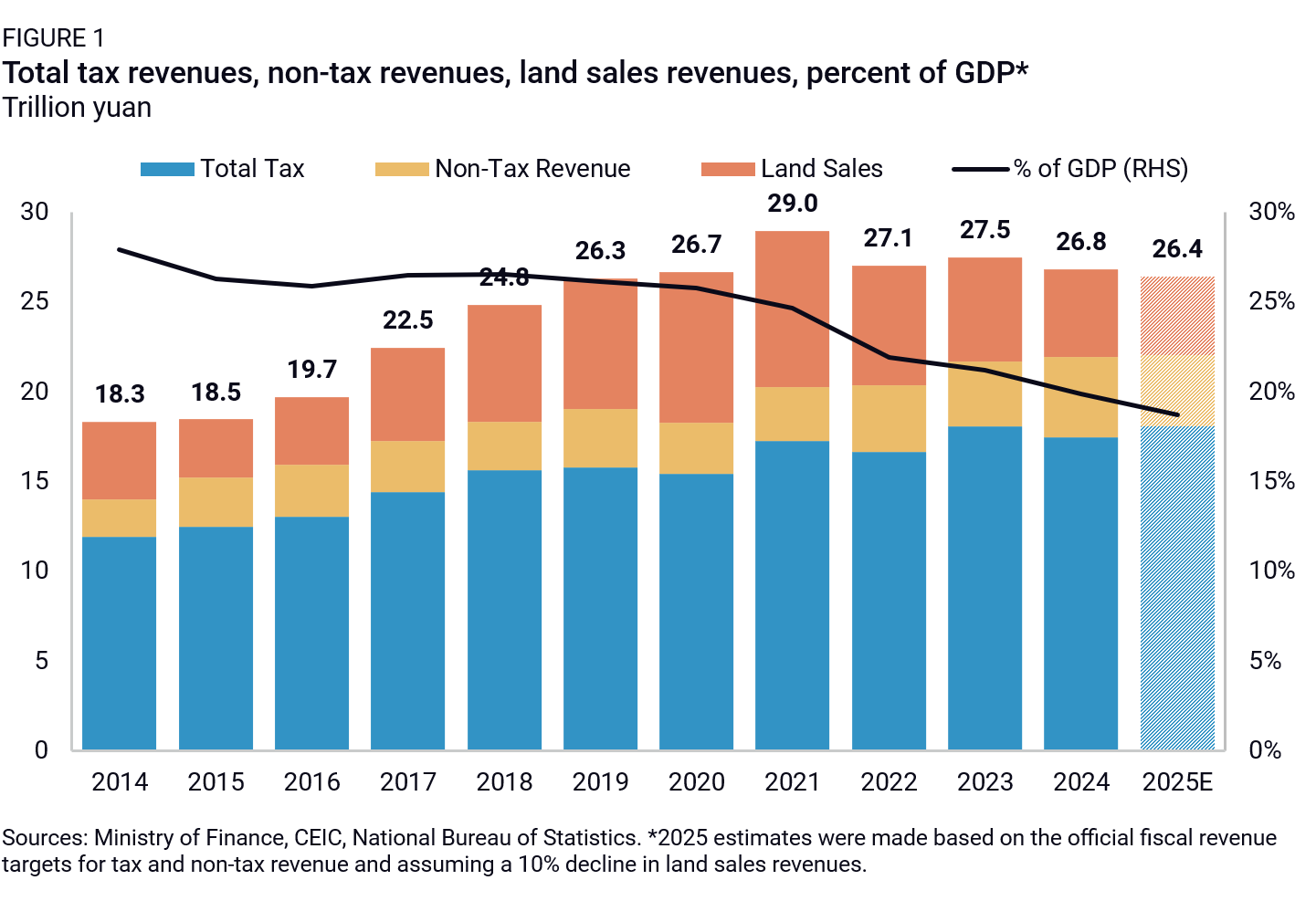

Including these three sources of revenue—taxes, non-tax revenue, and land sales proceeds—China’s aggregate fiscal revenues are likely to decline in 2025, even if China meets its full-year economic growth targets of “around 5%.” These combined sources of fiscal revenue peaked in 2021, and have basically remained unchanged in nominal terms since 2019 (Figure 1). Should China’s economic growth fall below 5%, which is highly probable, the decline in revenue growth this year could deepen.

It is difficult to understate the macroeconomic significance of these developments. The Ministry of Finance is essentially acknowledging that China’s fiscal resources are exhausted. China’s tax system depends upon investment-driven growth, and without those sources of investment growth, fiscal revenues have peaked in absolute terms, while also declining as a proportion of GDP. China can run larger budget deficits, and those deficits are basically guaranteed at this point. But the era of difficult trade-offs is here.

Persistent deflationary pressure in China’s economy has reduced nominal GDP growth in recent years (only 4.2% in 2024 officially), which has also impacted China’s tax revenues. For the first time, the Ministry of Finance seems to be anticipating that economy-wide deflation will continue as well. The official fiscal deficit target this year as outlined in the budget was 5.66 trillion yuan for 4% of GDP, which would imply anticipated nominal GDP growth of 4.9%, and a GDP deflator of -0.1%. Last year, China’s anticipated nominal growth rate was 7.4%, and official nominal GDP growth fell short of that implied target by over 3 percentage points. This year is the first time we can remember China anticipating falling prices and a negative GDP deflator for the full year.

The Ministry of Finance explicitly cites falling producer prices as a reason for its lower fiscal revenue projections as well, claiming in the 2025 budget report that despite China’s ongoing recovery, “insufficient domestic demand and the level of prices will continue to weigh down government revenues which are calculated according to current prices. Some major tax contributing industries are facing a slowdown in growth, and some enterprises are experiencing difficulties in their production and operations. China is also confronted with considerable uncertainty in foreign trade. These factors will negatively affect revenue growth. The scope for putting assets and resources to better use has also narrowed.”

The reasons for China’s declining fiscal revenues are clear. As we have argued extensively, the tax system depends upon investment-led growth, which is slowing significantly (See Aug 2023, “The Myth of China’s Fiscal Space”). China collects taxes via value-added taxes and enterprise income taxes, and taxes trade activity, with much lower tax collection levels on individual incomes (around 8% of tax revenues). Domestic consumption taxes are administered on only limited numbers of products, including alcohol, tobacco, automobiles, and fuels. If China’s economy were to rebalance toward domestic consumption-led growth, tax revenues under the current system would decline sharply.

At the margin, China can use some of its other accounts from managing state-owned enterprises and stabilization funds to dress up the full-year numbers and engineer some artificial stability. But on balance, as investment growth declines, tax revenues will weaken as well. The decline in investment-led growth is inevitable given the ongoing decline in China’s credit growth (See Jan 2023, “The End of China’s Magical Credit Machine”).

Land sales collected by local governments are particularly under pressure because of the adjustment in China’s property sector, and the declining financial capacity of property developers to buy land. Land sales revenues dropped from a peak of 8.7 trillion yuan in 2021 to only 4.9 trillion yuan in 2024. Because land auction proceeds are paid to local governments with a one-year lag, it is highly probable that land sales revenues will decline further in 2025, based on lower sales levels in 2024. Eventually, the property sector will stabilize, and there are some signs of stabilization already, but it is unlikely that land sales themselves will become another reliable driver of fiscal revenue growth in the future.

Rising fiscal deficits and their implications

Officially, China ran a fiscal deficit of 3% of GDP in 2024, after all of the adjustments to the formal fiscal revenue totals from stabilization funds. But the more accurate picture of the deficit emerges from Figure 2, which is the combined deficit of China’s general obligation budget and “fund budget,” which is the secondary fiscal account managed by local governments. That combined deficit has risen from only 1-2% of GDP in 2011-2014 to 7.7% of GDP in 2024. It is likely to rise to around 8.5-9.0% of GDP this year.

The argument against aggregating the central and local government deficits as above is that this is not directly comparable to other economies where state and local debt is not recognized explicitly on the central government’s balance sheet. But in China, this is all part of a unified fiscal system, in which the central government collects more tax revenues and makes substantial transfers to provincial governments who execute almost 90% of the total spending. The aggregate spending in this process relative to both central and local government revenues is the most relevant measure to use in estimating the nationwide fiscal deficit.

The more alarming conclusions emerge when looking slightly over the near-term horizon. Spending totals are likely to continue increasing gradually, which will probably widen deficits toward more than 10% of GDP in the years ahead if revenues are essentially flatlining or declining. These deficits can both expand and remain financed internally, but they will require larger volumes of government bond issuance every year, both among central and local governments.

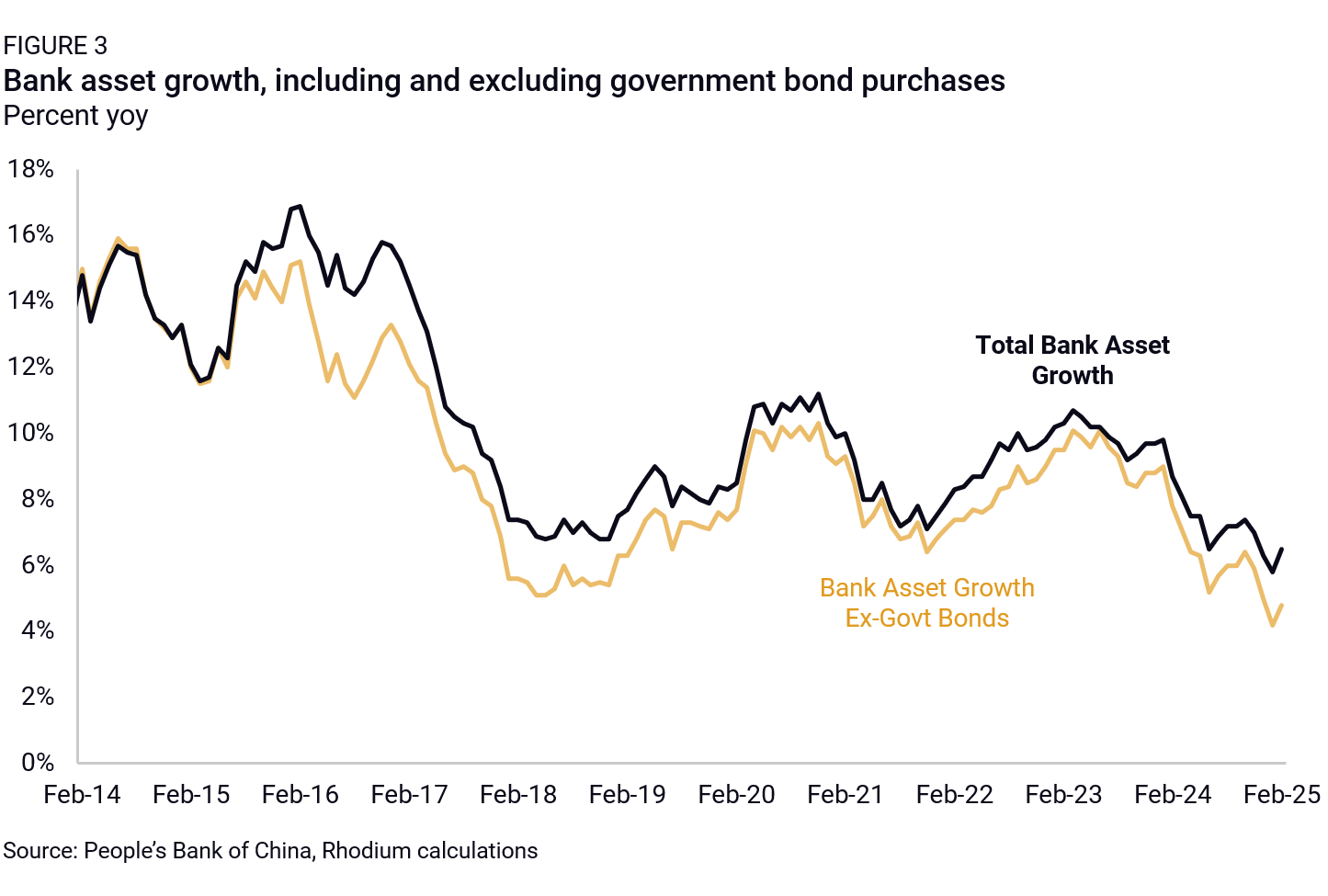

Banks have historically bought most of these government bonds, while insurers have bought more long-term issues. But total bank asset growth is constrained by declining profitability and capital requirements, which means that banks cannot absorb the continued rise in government bond issuance without reducing lending to the real economy and the private sector. This is exactly what has happened in recent years. Government bonds are already a large share of marginal bank asset growth, representing 22% of new assets over the past five years. In 2014, government bonds were only 4.1% of total bank assets, rising to 14.7% by February 2025. In the first two months of 2025, total bank asset growth excluding government bond purchases—a measure of credit extended to the corporate sector—has fallen below 5%, the slowest growth rate in history (Figure 3).

The best arguments that China still has fiscal space, such as Brad Setser’s article on this topic from September 2024, focus on the central government’s ongoing capacity to finance itself at low interest rates below rates of nominal growth. But this logically raises issues related to the domestic financial system’s capacity to absorb that new bond issuance, whether the underlying new fiscal spending growth can actually generate any economic growth because of the inefficiencies of local governments, and the tradeoffs involved for credit growth in the rest of the economy. All are in question at present.

The larger problem is that even the current rates of nominal growth may not generate any new growth in tax collection under the current system. After all, 4.2% nominal growth in 2024 corresponded with a reduction in aggregate tax revenue of 3.4% last year, with declines of 3.8% in value-added taxes and 0.5% in enterprise income tax, the two largest categories of revenue. If most fiscal resources are eventually spent by local governments and invested via financing vehicles, most LGFV projects still generate only 1% returns, below even the borrowing costs on local government bonds. This would reduce the revenues accruing to local government funds over time. A further slowdown in credit growth would further reduce investment growth, and fiscal revenue as well.

PBOC must come to the rescue

These fiscal pressures place the PBOC’s recent quantitative easing measures in starker relief. The central bank is likely to become the long-term buyer of last resort for government bonds, to reduce financing costs for local governments and to allow banks to continue lending in larger volumes. Any pause in official government bond purchases—as the PBOC announced in January—is likely to be temporary. The PBOC will simply be unable to stay on the sidelines without seeing a significant slowdown in credit growth.

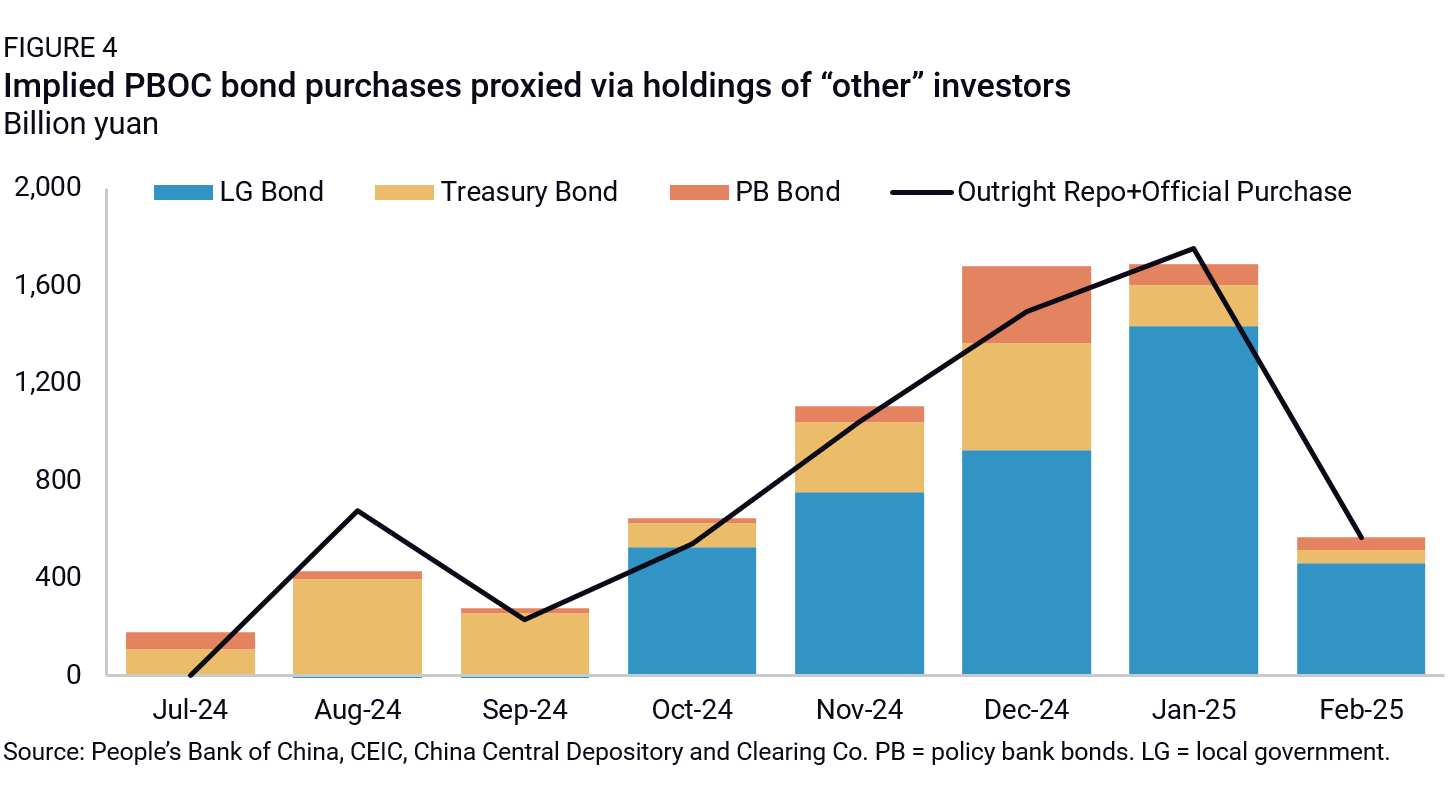

After MLF and PSL funding is retired, which could occur over the course of the next two years, government bond purchases will become the primary tool for the PBOC to expand its balance sheet. This is already occurring in larger quantities, as proxied through the holdings of “other” investors in the China bond clearing house data series (Figure 4).

The PBOC has not declared direct purchases of government bonds in January or February 2025, but has continued to expand its funding for the banking system through outright repo transactions, including net additions of 400 billion yuan in February (the blue line in Figure 4 above). The bond clearing house data suggests these transactions are being used to add government bonds to the central bank balance sheet while the underlying repo transactions are being rolled over. Recent purchases have been heavily concentrated in local government bonds.

Choices, choices

The likely effect of this expansion of the fiscal deficit, along with the corresponding monetization of government debt, will be a weaker exchange rate, which in most circumstances will be accompanied by lower interest rates over time as well, to manage the growing debt burden. Comparisons to Japan’s fiscal condition in recent years, which are already quite common, will proliferate further.

The harder choice for Beijing—besides deciding when to allow the exchange rate to depreciate—will be deciding how to raise tax revenues quickly without weakening the economy further. There are clear options available for expanding the base of consumption-based taxes to reduce reliance upon investment, but none are likely to raise significant volumes of revenue in short order. Property taxes typically raise less than 2% of GDP in most economies, and there will be much more reluctance to adding them in a flagging property market than in the past. The Third Plenum meeting last July was expected to unveil at least the framework for new measures to raise or restructure tax revenues, but it did not. No structural fiscal reform appears on the horizon at present. If one follows the policy-making pattern seen in response to the problems created by zero-COVID, the one-child policy, or last year’s economic slowdown, Beijing will finally acknowledge reality and pivot only after it is far too late.

Beijing’s other short-term option is to try to use supply-side controls to reduce deflationary pressure and raise prices. This is easier said than done, given the number of industries facing overcapacity at present, and the importance of state-owned players within those industries. Most likely any effort that would actually boost aggregate prices would still reduce tax revenues because of the negative impact on overall industrial output.

The rest of Beijing’s choices are much more difficult: deciding what to cut from its long-term fiscal obligations. China’s most significant regular allocations of fiscal spending are made at the local level for education, social security, health care, and agriculture. China has obligations to its citizens that it needs to meet without generating considerable public discontent, and those shortfalls in local resources will expand in the years ahead. Basic social services at the local level are still unlikely to be cut. Industrial policy and external lending will likely become more selective in the future. The subject of spending patterns and constraints requires a far more extensive discussion than in this brief note, but the key point is that China will still retain wide discretion to reapportion fiscal resources or even increase spending in some areas even under these constraints, such as in defense, for example.

But the era of trade-offs is here already, not over the horizon. There are no easy choices for Beijing, as both fiscal revenue and credit from the financial system—the primary state levers of control over the economy—are rapidly approaching capacity constraints.