The Myth of China’s Fiscal Space

China’s fiscal capacity is now very limited, because Beijing’s tax system is dependent upon an investment-led growth model that is ending.

China’s fiscal capacity is now very limited, because Beijing’s tax system is dependent upon an investment-led growth model that is ending. Weakening property and land markets have widened domestic fiscal deficits, which will reduce Beijing’s future policy ambitions, including support for strategic industries. Local government debt restructuring will also incur large short-term fiscal costs. Restructuring China’s fiscal system is essential, but likely involves new taxes, including levies on households and consumers.

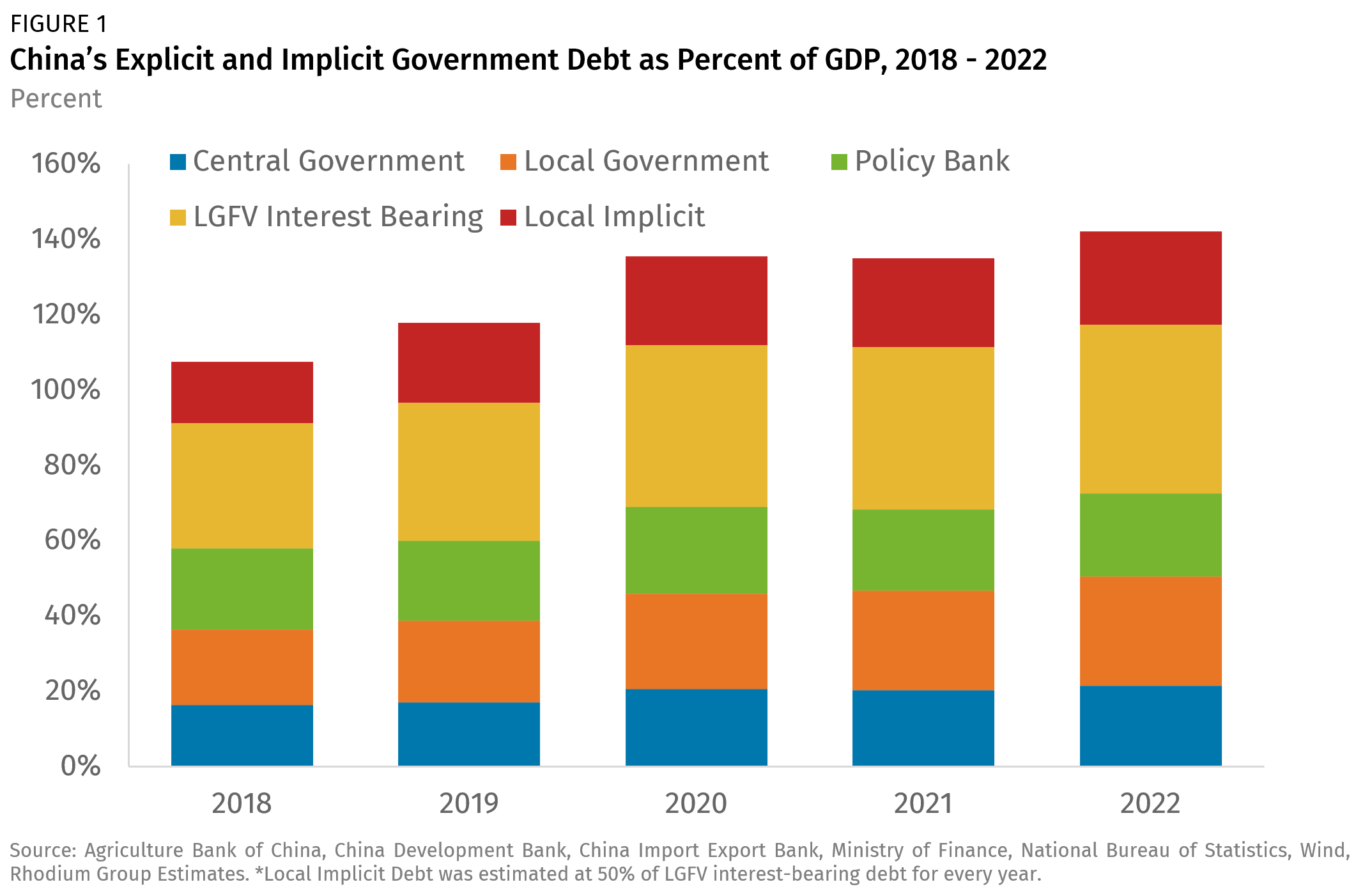

Conventional wisdom holds that China has numerous economic and financial problems, but Beijing has “fiscal space” to manage them. China’s central government debt-to-GDP ratio is only 21.3%, extremely low compared to the US level of 119%, and the Eurozone average of 91.6%. Most analysts argue that China can use this space to restructure local government debt, while also maintaining other economic policy priorities, such as subsidizing and financing strategic industries.

In reality, China’s fiscal capacity is highly constrained. The entire fiscal system is structured around revenues from investment-led growth, which is ending. Tax revenues continue dropping relative to the size of the economy, and the property market’s decline has hit land sales revenues as well. Actual fiscal deficits, including both central and local government budgets, are around 6-7% of GDP, and are likely to stay in this range, or rise. Persistent deficits of that size can be financed internally, of course. But they will limit not only Beijing’s ambitions for strategic spending, but also the use of fiscal stimulus to support growth in the years ahead.

As Figure 1 shows, a conservative estimate of China’s total government debt in 2022 is closer to 142% of GDP. This includes central government debt, policy bank debt, local government debt, local government financing vehicle (LGFV) debt, and other implicit debt incurred by institutions such as schools and hospitals.

Obviously, every category outside of central government debt would be contingent rather than formal liabilities for Beijing. But they are also immediately contingent; a portion of this debt is likely to be recognized on the central government’s balance sheet, and soon. The Politburo’s mid-year statement on the economy contained a pledge to take a “comprehensive” approach to address the local government debt problem. Such a restructuring would reduce Beijing’s fiscal capacity to address other policy priorities, and would presumably involve limits to future local government investment growth as well. Hence the idea of China’s “fiscal space” deserves some reconsideration.

Localities’ Sisyphean Task: Maintaining Investment Growth

Whatever basket of measures is announced to address local debt will probably slow future local investment growth, and therefore economic growth over the next few years. Beijing’s challenge is maintaining market stability and current financing channels for localities without reinforcing the moral hazard that allowed debt levels to rise. The other key task is finding a new channel to sustainably finance local government investment.

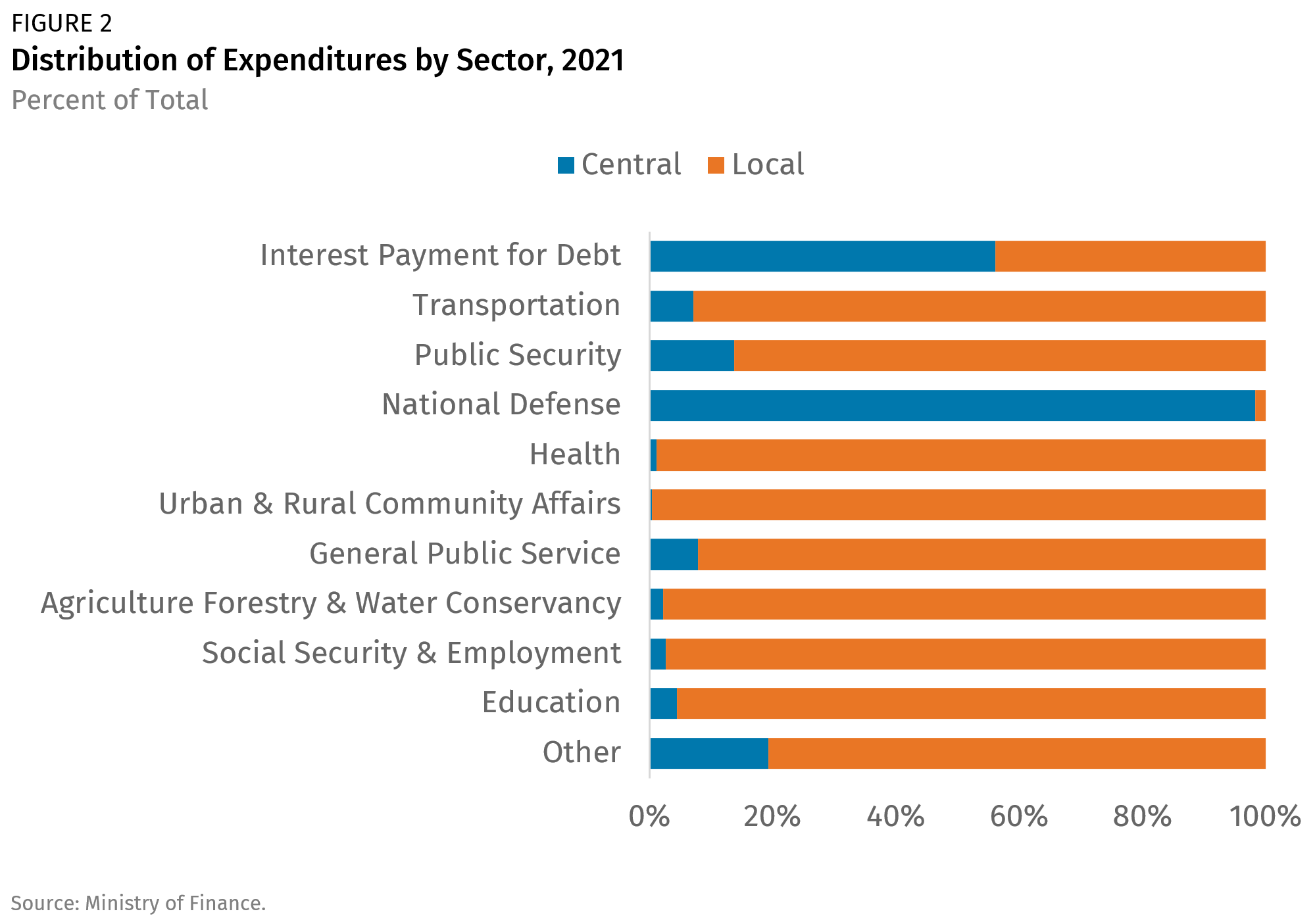

Local governments are responsible for the majority of social services in China, while Beijing controls the majority of tax revenues, and transfers money to local governments to meet their needs (Figure 2). This structure was created in the 1994 tax reforms, which were designed to limit localities’ capacity to independently raise money for investment, following a surge in local spending and inflation jumping over 20% in the wake of Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour.

Despite the limits imposed by Beijing in 1994, local governments continued competing with one another to generate investment, employment, and economic growth. To bypass Beijing’s oversight, localities relied upon land sales as a source of revenue from secondary “fund budgets” at the local level, and structured quasi-fiscal spending as borrowing from local banks through local state-owned enterprises or financing vehicles. Shadow banks and informal borrowing supplemented formal bank loans to local firms and LGFVs.

Localities simply cannot afford to service existing debts while expanding investment. The median return on assets for LGFVs in 2022 was 1% and interest rates on LGFV debt averaged 5.36% (See “Tapped Out”). Local government investment now accounts for around 14-15% of GDP. If local government revenues continue to fall and local governments or LGFVs suddenly lose access to credit, then investment, employment and growth in China’s broader economy will suffer.

Local governments need both lower-cost financing channels and new revenue streams to service debt and expand investment in the future. But the broader policy question is how much growth in local government investment Beijing wants to see in the decade ahead. Investment is likely to slow in order to prevent another debt problem from rising, but the pace of decline remains unclear.

Central-Local Tax Imbalances

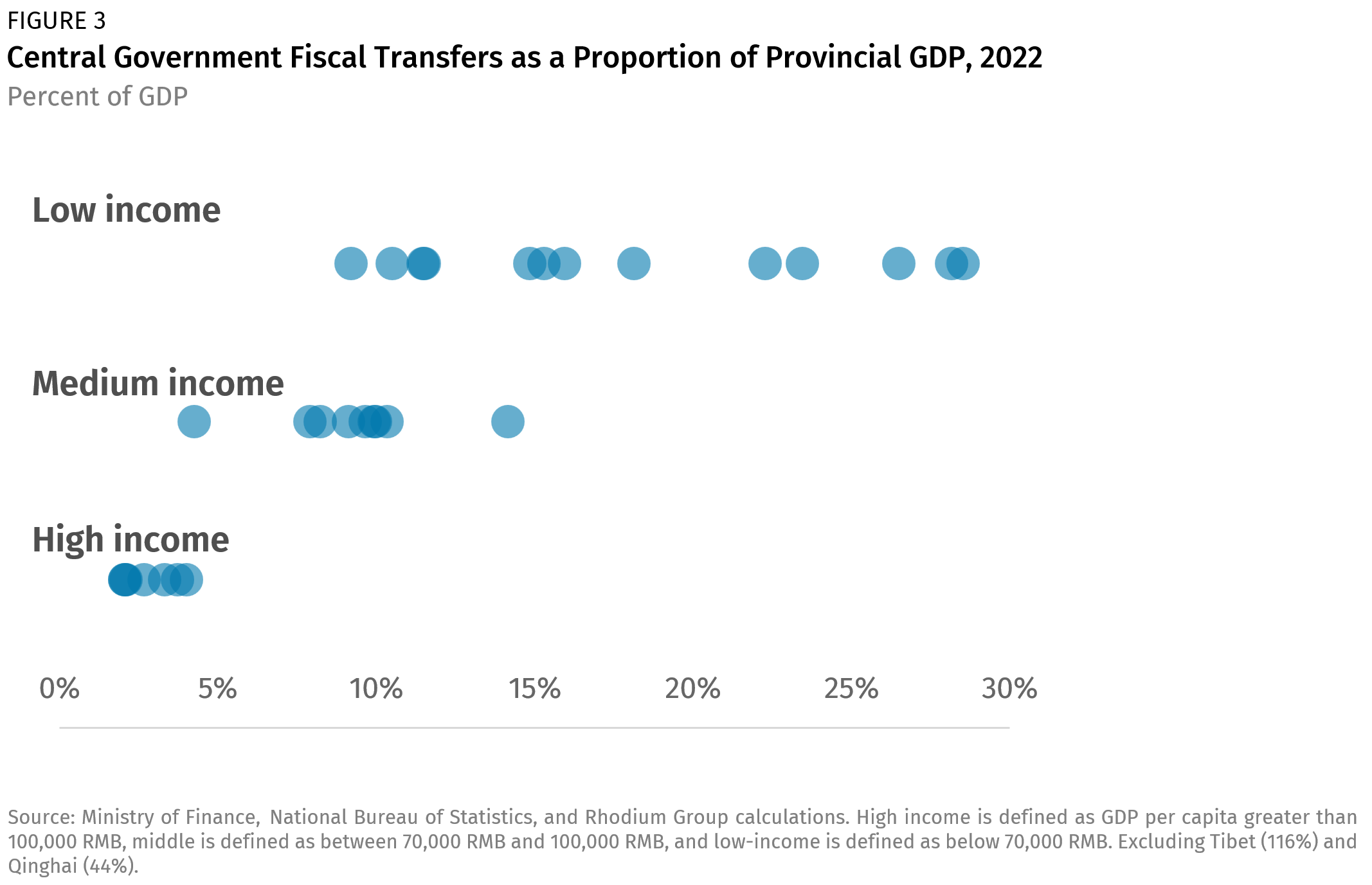

Under China’s fiscal structure, most tax revenues are shared at the central and local levels, and then transfers are made from the central government to meet spending obligations. The two largest sources of revenue for local governments in 2021 were value-added tax (38% of tax revenue) and corporate income tax (18%). VAT revenues are closely linked to both industrial output and manufacturing, including within the export sector. China’s corporate income taxes are paid to the provincial government that hosts the corporate headquarters. In 2021, over half of China’s corporate income taxes were paid to Shanghai, Beijing, Jiangsu, Zhejiang and Guangdong. As a result, the two largest sources of local tax revenue favor high-income provinces, which makes them less reliant upon the central government for fiscal transfers (Figure 3).

Because the central government controls tax rates, poorer provinces are left to identify additional non-tax revenues, through fines or administrative fees. Alternatively, they have become heavily dependent upon land sales. China’s provinces with the weakest tax bases are the most exposed to the decline in land revenues from the flagging property market.

Land Revenues and China’s Deteriorating Fiscal Outlook

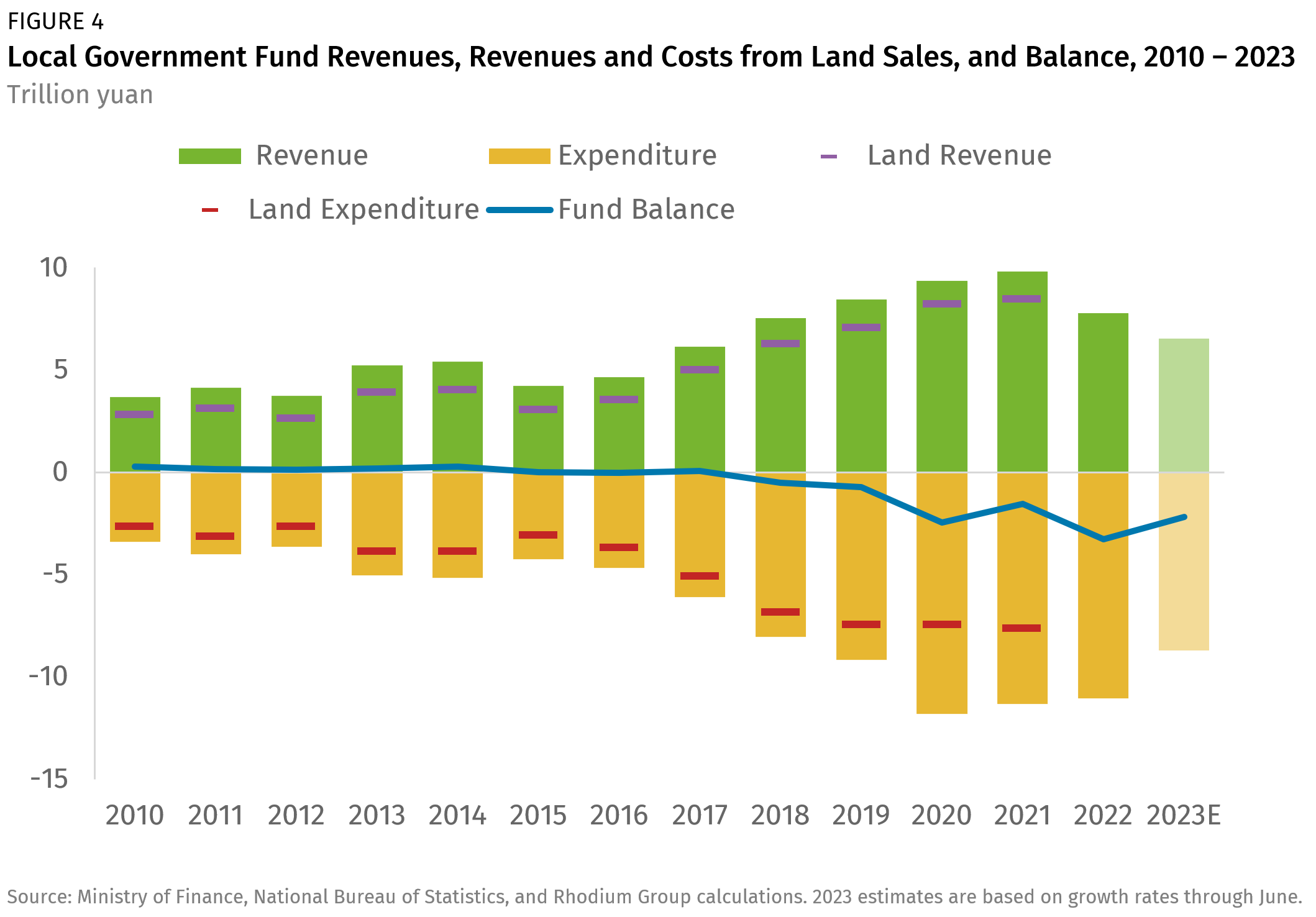

The property market’s decline has intensified the pressures on local fiscal revenues. But local (fund) budget deficits were already widening even before the property market’s recent decline (Figure 4). This was primarily because expenditures associated with land development before sale had been rising during the shantytown redevelopment program from 2014 to 2020, which involved compensating residents to move to different homes.

Since 2021, land sales have declined at a faster rate. This impacted both the revenue and expenditure sides of local government fund budgets, as land does not need to be prepared for sale through compensating resettled residents. Total land revenues fell by 2.0 trillion yuan in 2022, and are on pace to decline by a further 1.4 trillion yuan in 2023 (down 21% ytd).

The decline in land and property sales also impacted VAT revenues. Pre-construction sales declined from 14.7 trillion yuan in 2021 to 10.3 trillion yuan in 2022. Applying the 9% VAT rate to presales revenue, total VAT revenues declined by approximately 400 billion yuan in 2022. This is meaningful because if the 9% tax rate is applied across the board (developers with sales below a certain level pay only 5%), an estimated 19.1% of VAT tax revenues and 5.6% of China’s total tax take came from VAT on pre-construction sales of homes alone, even when property sales declined so sharply.

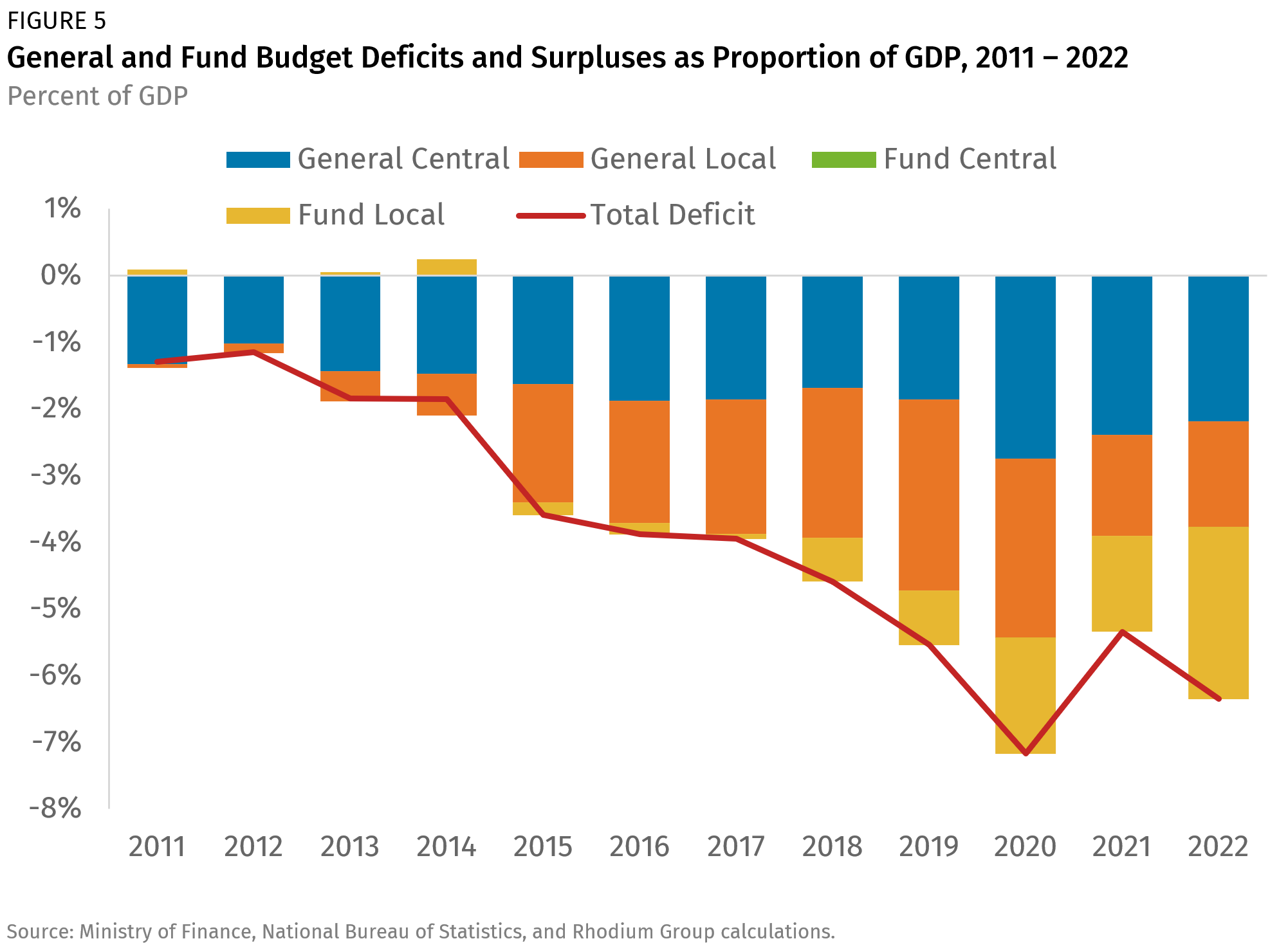

The weakness in China’s land sales revenues has contributed to rising de facto fiscal deficits in recent years. As Figure 5 shows, the widening local government and local fund deficits since 2015 have driven an expansion in China’s aggregate fiscal deficits from an average of 1.5% of GDP from 2011 to 2014 to an average of 6.3% of GDP over the past three years. The aggregate deficit is likely to remain around these levels in 2023.

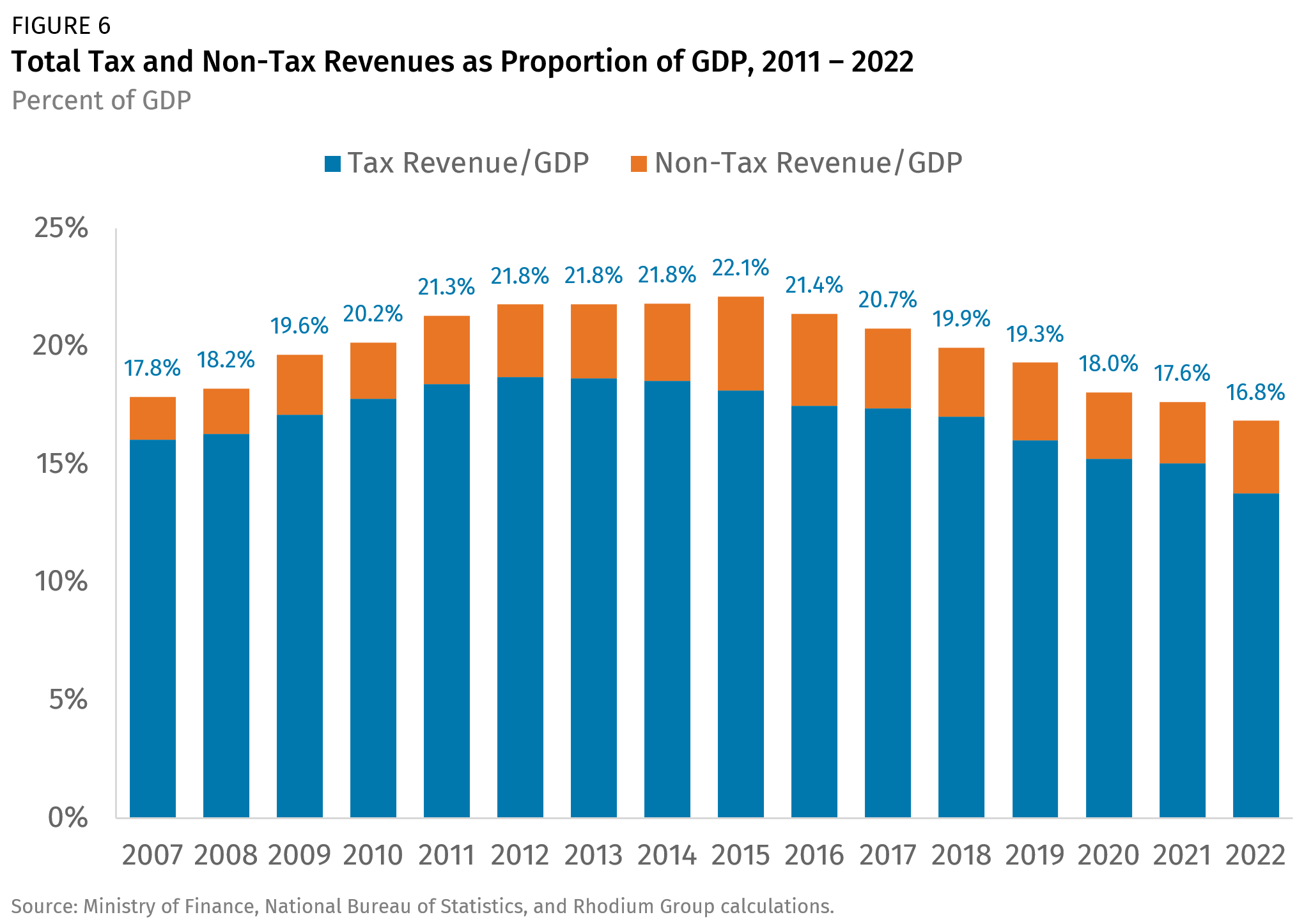

Some of the expansion in the deficit was related to pandemic-era tax cuts, as well as significant VAT rebates in Q2 2022. But there is a much broader decline in tax revenues underway (Figure 6).

The broad-based decline in tax revenues reflects the fiscal system’s dependence upon investment-led growth. As investment growth has slowed in recent years, so have China’s tax revenues relative to the economy. Total tax revenues fell from 18.5% of GDP in 2014 to only 13.8% in 2022. In nominal terms, growth in China’s overall tax revenues has averaged only 4.4% since 2015. In comparison, OECD average tax revenues to GDP are consistently above 30%, and reached 34.1% in 2021.

China’s taxes on domestic consumption (10% of total tax revenues in 2022) and individual income (9%) are small. If investment and industrial and manufacturing output slow, China’s tax base will weaken as well. This process appears to be well underway. Consumption-led growth within China’s current tax system would imply wider fiscal deficits and weaker capacity for fiscal spending. Notably, both domestic consumption tax revenues (down 10.6% ytd) and individual income taxes (-0.6%) have fallen so far in 2023.

For local governments, the urgency to restructure their revenue streams is greater, as land sales revenues are never likely to regain their previous levels, nor will they provide a sustainable foundation for growth. Adjustments can come in the form of changes to existing tax allocations, tax rates, levels of expenditure, or expenditure responsibilities.

One option would be to reduce the proportion of VAT revenues accruing to the central government budget. Localities still only receive 50% of value-added tax revenues but are on the hook for 80% of total expenditures.

A property tax has long been considered as an alternative revenue source for localities, and it remains necessary at some level. However, there will now be more political resistance to kicking the property market when it is down. A property tax is not a silver bullet for China’s revenue shortfall either, as OECD averages of property tax revenues remain below 2% of GDP.

The central government could also assume greater responsibilities for social services, particularly local unfunded pension obligations. Increasing the expenditure responsibilities of the central government would ease pressure on local government finances but would contribute to an already high and growing fiscal deficit, and would likely displace additional spending priorities.

Increasing central government tax rates while centralizing tax revenues could help to maximize Beijing’s transparency over local fiscal conditions. But it would also likely increase the incentives for local governments to rely upon off-budget financing, as greater oversight would likely involve greater accountability for local officials to meet multiple objectives.

Raising new taxes will also be necessary. The most obvious place to expand China’s tax base would be within the domestic consumption tax, which currently only covers items such as autos and purchases of alcohol and tobacco. This should probably be expanded to a much wider range of consumer goods or applied at the level of a retail sales tax, but obviously this would also slow consumption growth and rebalancing. Another option would be taxing data-related consumer services from Internet platform companies, given the central government’s recent emphasis on data as one of China’s critical economic resources. Indirectly this may also pressure China’s households.

Scaling Back Beijing’s Fiscal Ambitions

The real impact of China’s constrained fiscal capacity will be limits on Beijing’s ambitious long-term policy objectives. As China continues to run large deficits relative to GDP, ramping up those deficits further to stimulate the economy becomes far more difficult. Similarly, fiscal revenues are not unlimited, and are now shrinking relative to the size of the economy. Beijing will become less capable of sustaining policy objectives in the future, or will have to make trade-offs between them.

- Pension and social security expenses increased 8.3% per year over the past five years and are set to accelerate as China’s working age population declines. As the workforce shrinks, increased social security expenditures will consume a larger proportion of local budgets.

- Over the past decade, China’s national defense spending increased 8.2% per year. With GDP growth rates continuing to decline and revenue streams under pressure, plans to continue growing national defense expenditures at current rates will become constrained by the declining tax base. Beijing can always maintain defense spending as a high priority, but it is unlikely to expand significantly faster than the economy as a whole.

- Environmental technology investments to prepare China’s economy for a lower-carbon future will require tens trillions of yuan of new investment in the years ahead. Only a small portion of this can be funded directly via fiscal outlays, but financing such investments using commercial terms is likely to slow the overall buildout.

- China’s industrial policy in developing self-reliance in strategic industries, including the “dual circulation” plan, will depend upon policy-led investment that will be more difficult to maintain.

- Science and technology-related spending remains a priority, and budget allocations to key national labs for basic research will remain intact, but local government funding for applied research and investment in strategic industries will need to trade off against other priorities at the local level.

- China relies upon policy banks’ external lending to fund overseas infrastructure, extend political influence, and expand its own export markets. But policy banks have seen significant losses on those loans in recent years, with an estimated $78 billion in overseas loans either in default or being renegotiated since 2020 (See “China’s External Debt Renegotiations After Zambia”) and authorities may balk at additional borrowing or recapitalization of these banks to absorb losses and provide debt relief to emerging markets in the context of rising domestic fiscal obligations.

China’s fiscal capacity is far more limited today than in the past. Urgent changes to China’s fiscal system are necessary to accommodate a consumption-led growth model in the future, including adjustments to tax rates, tax coverage, and revenue sharing between central and local governments. Until then, Beijing will struggle to use fiscal policy either as an effective counter-cyclical tool or as an instrument to achieve longer-term policy objectives.