If Not Tariffs, Then What?

Concerns are mounting in Brussels that existing tools may be insufficient to address the spillovers from China’s deep domestic imbalances and policies designed to capture global market share. What policy options are available to the EU?

On top of seismic tariff and foreign policy shifts from Washington, Europe faces significant and growing trade disruptions from China, which threaten its competitiveness and industrial ecosystem. Concerns are mounting in Brussels that existing tools may be insufficient to address the spillovers from China’s deep domestic imbalances and policies designed to capture global market share. US tariff increases announced on April 2—particularly high on China and several Southeast Asian countries—are likely to redirect a surge of exports from these markets to Europe. What policy options are available to the EU?

A growing threat to EU industry

A year ago, we published two notes examining the growing imbalance between Chinese production and consumption, and its impact on emerging economies. China’s growth model depends on expanding its share of global manufacturing while discouraging investment and production in other countries through lower prices and increased competition.

These challenges are unlikely to subside. Key indicators of sustained market distortions have not improved—in many cases, they have worsened. In key sectors like metals, special equipment, automotives, and electric equipment, China’s capacity utilization rate continued to decline throughout last year. Meanwhile, the share of loss-making companies has continued to rise, reaching 23% by December 2024 from 21% in 2023. Deflation continues to worsen, with China’s producer price index declining year-on-year every month since October 2022 and Chinese export prices falling every month since May 2023. Beijing’s policy response has fallen far short of the structural reforms needed to address the root causes of its overcapacity.

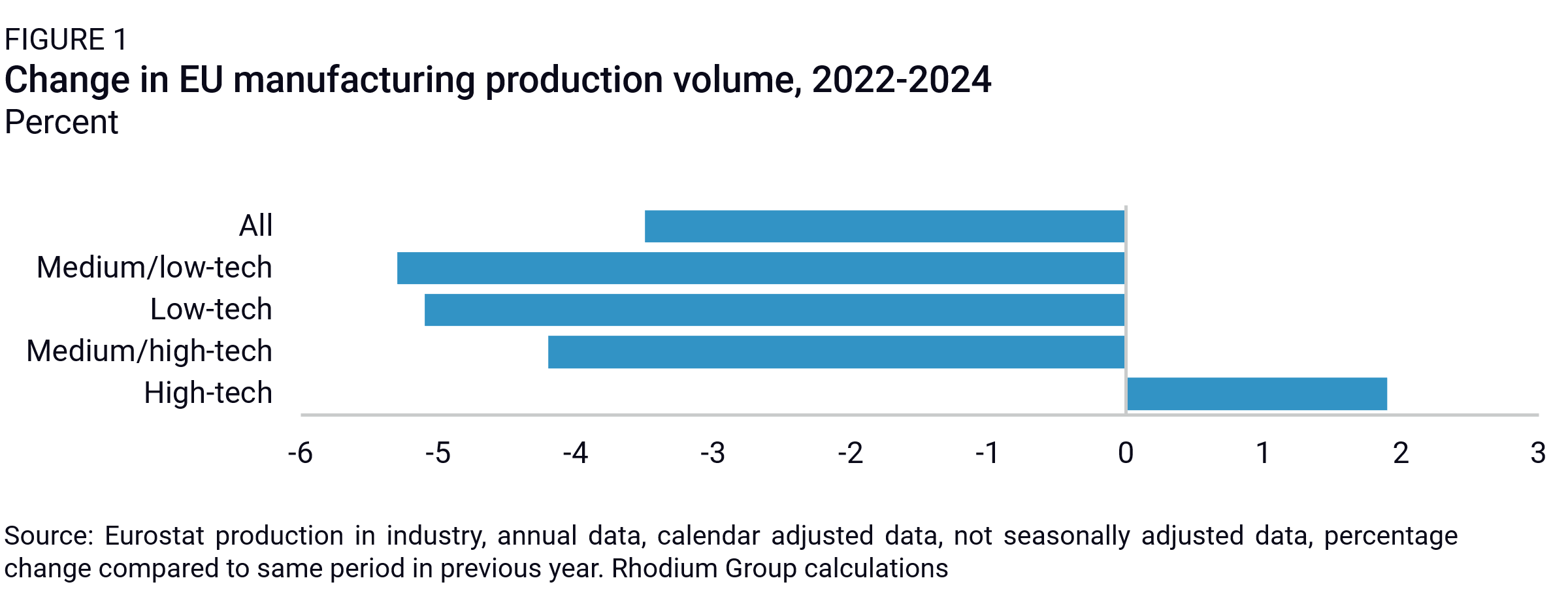

Early indicators suggest that the rapid increase in these imports is already straining Europe’s competitiveness and industrial output. In just two years, from 2022 to 2024, manufacturing production volume in Europe has declined by 3.5%, with much of this downturn concentrated in low- and mid-tech manufacturing (Figure 1). This comes after a general rise in previous years, with EU manufacturing production increasing by 15% between 2014 and 2022. Germany (-5.4%) and some countries in Eastern Europe and the Baltics (-12.7% for Estonia, -8.3% for Hungary, -7% for Bulgaria, and -6.2% for Austria) have been particularly affected. A similar picture emerges for EU manufacturing value added, which dropped 3% between 2022 and 2024, after rising by 17% from 2015 to 2022.

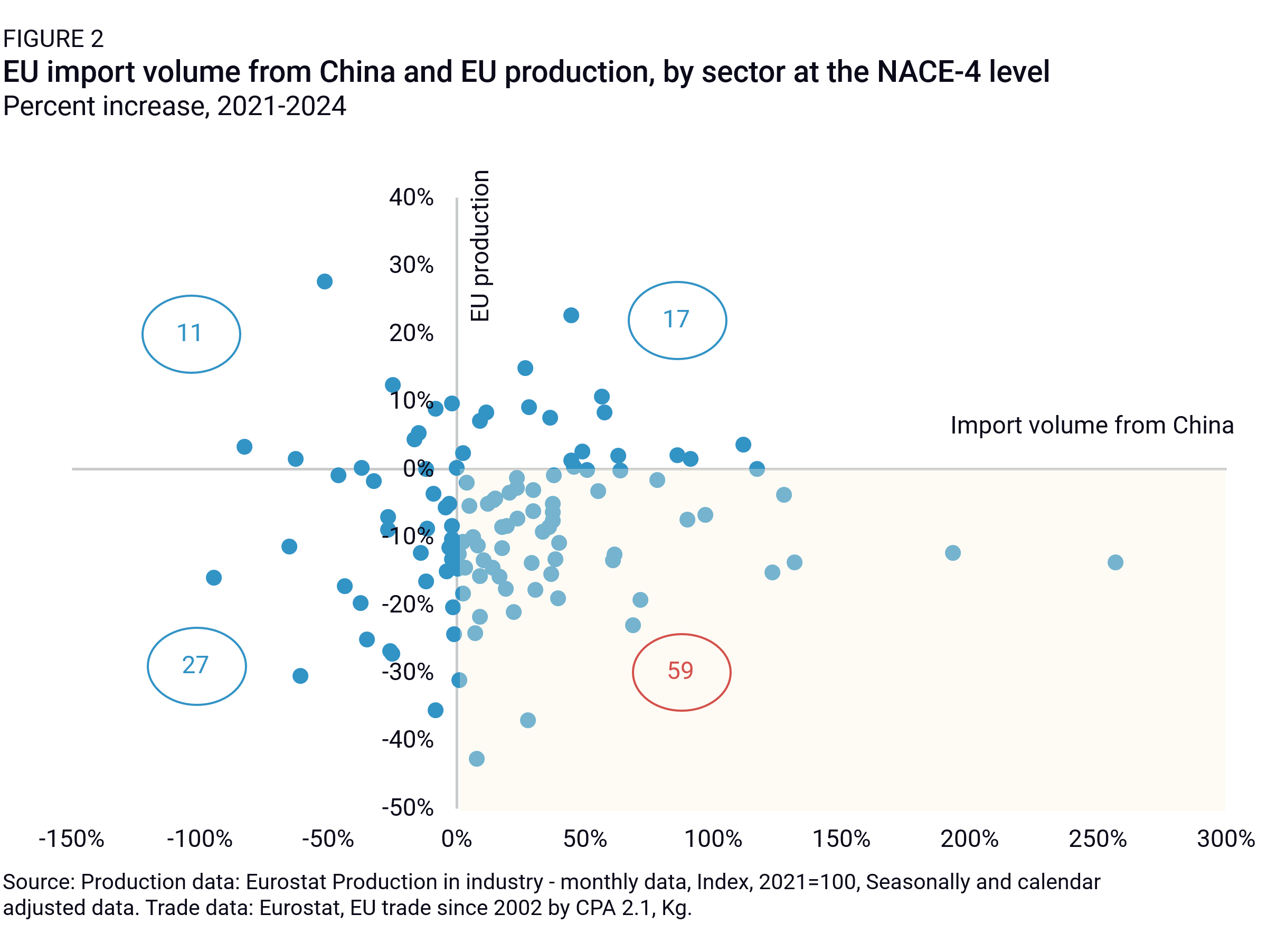

Of course, rising imports from China are not the sole factor behind this decline. High energy prices, sluggish economic growth, weakening demand, and trade fragmentation have also played significant roles. However, there is a clear correlation between rising Chinese imports and declining production across multiple sectors (Figure 2). In half of the product categories at the NACE-4 level (59 out of 114), rising imports from China coincided with decreasing production in Europe.

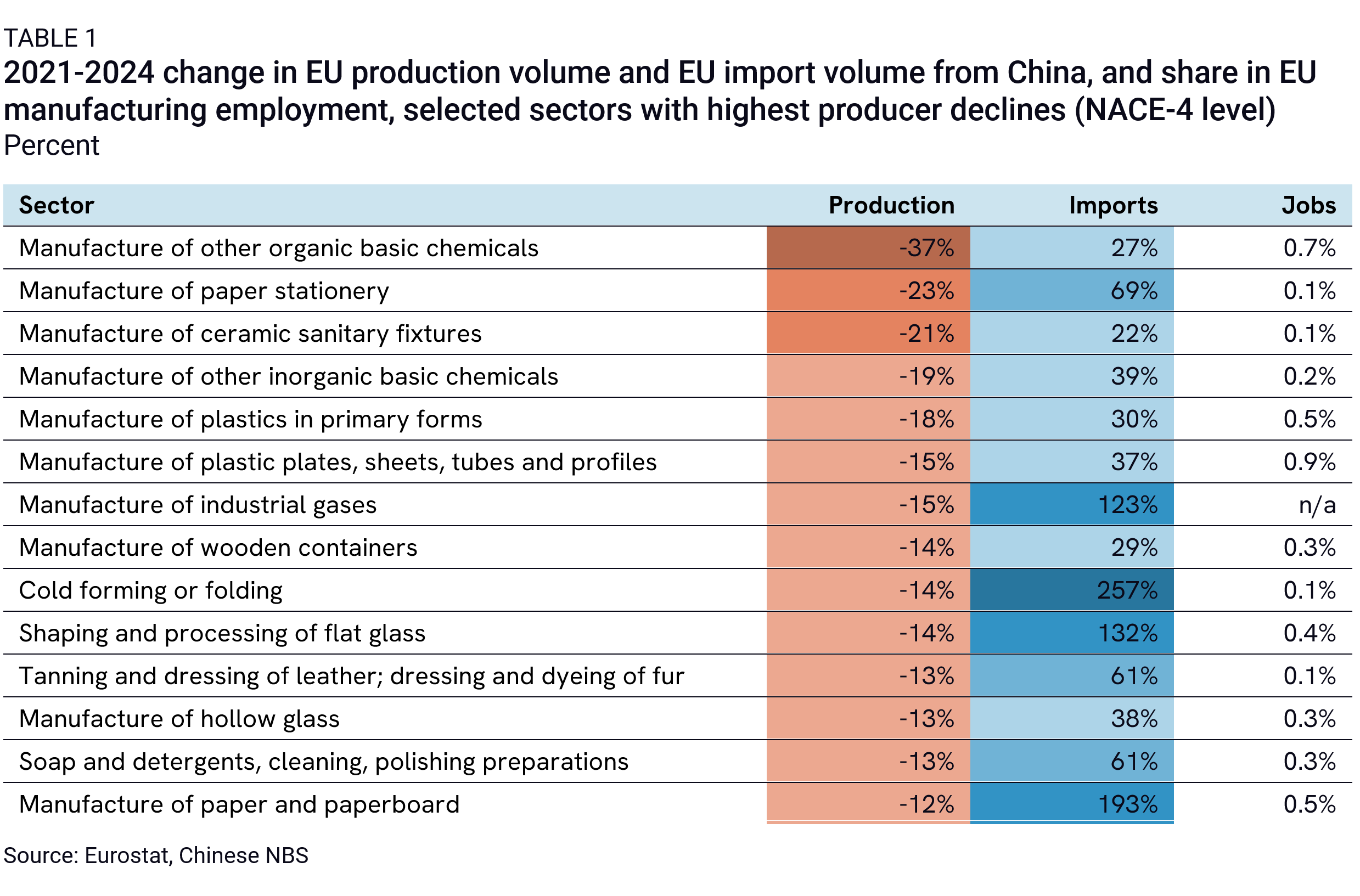

Some of the sharpest declines in EU industrial production and the largest increases in Chinese imports are concentrated in heavy industries facing a dual challenge: China’s high overcapacity (and falling prices) on the one hand, and Europe’s rising energy costs on the other (Table 1). Chemicals and plastics stand out. These industries are energy-intensive and European companies have repeatedly warned that high energy costs are eroding their competitiveness. At the same time, they have long struggled with overcapacity in China.

Collectively, the industries experiencing both rising imports from China and falling production in the EU account for 25% of Europe’s manufacturing jobs.

Other, less energy-intensive sectors also face declining industrial production in Europe and rising imports from China. Paper, wood, and furniture fall into this category. They all display signs of intense strain from weak consumer demand in China: rising inventories, increasing share of loss-making firms, falling profits, and declining production prices.

These sectors also make up a significant share of EU employment, magnifying the economic and social consequences of their decline. Collectively, the industries experiencing both rising imports from China and falling production in the EU account for 25% of Europe’s manufacturing jobs. Industries where these trends are particularly pronounced—such as plastics, chemicals, paper, and furniture—are also among the largest employers in the sector. Even this is a conservative estimate, which excludes key industries like automotive due to a lack of consistent data.

Overall, in 2024, the number of people employed in European manufacturing fell by 0.4%, and by 0.7% when compared to 2019. Although the overall unemployment rate improved in the past two years, it worsened in countries that have been most affected by declining manufacturing production, such as Estonia (+2%), Hungary (+0.9%), and Germany (+0.2%).

Europe may feel the effects of China’s domestic imbalances even more acutely in the months to come due to renewed trade tensions with the United States. The Trump administration’s announcement of “reciprocal tariffs” on April 2 subjects China to an additional 34% tariff on goods exported to the US, reportedly on top of the existing 42% resulting from previous rounds of tariff increases. These high tariffs, combined with weakened US consumer demand, could lead Chinese exporters to further reduce their prices, incentivize Beijing to let the RMB depreciate, and drive a shift in trade flows as Chinese exports are redirected toward alternative markets. Other countries are also likely to tighten their own trade barriers in response, meaning that if Europe is slow to act, it risks becoming the de facto dumping ground for surplus Chinese production.

The EU’s existing legal options

Europe faces a critical challenge. It must shield its economy from the distortions created by China’s industrial policies and domestic imbalances, while also minimizing inflationary pressures on consumers and downstream industries. Trade barriers are likely to be part of the equation, but the key question is which instruments to use.

From an economic perspective, there is no definitive case for prioritizing one type of trade barrier over another, whether tariffs or non-tariff measures. All options involve trade-offs across different parts of the economy, including upstream and downstream producers, industrial workers, and consumers. Ultimately, the core issue is what is legally and politically feasible in the European context.

The EU’s current options are still shaped by its strong commitment to the WTO system—a reflection of the bloc’s need to maintain unity among its 27 member states within a rules-based union—even though some voices in Brussels are now calling for a rethink. The WTO allows its members to use three main instruments to address trade distortions: antidumping (AD) duties against products sold by exporters at a price lower than in their own home market, countervailing duties (CVD) to counteract trade-distorting subsidies, and safeguards to provide temporary relief to domestic industries facing sudden import surges.1

In recent years, the EU has also introduced an array of new instruments to address gaps in the WTO framework. Brussels insists that these tools are WTO-compliant, though some of its partners have expressed reservations. The Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR), for example, targets market distortions caused by foreign state subsidies, ensuring that companies benefiting from such support do not distort the EU’s internal market. Although untested, the International Procurement Instrument (IPI) is another potentially powerful tool which aims to ensure reciprocity in public procurement. It allows the EU to restrict or condition access to its public procurement market for companies from countries that do not provide similar access to European firms.

In practice, governments worldwide—including the EU—also increasingly rely on a growing range of non-tariff barriers. These include, among others, product safety regulations, labeling requirements, environmental sustainability standards, cybersecurity rules, and industrial resilience policies. While such measures are formally regulated under the WTO’s Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement and Sanitary and Phytosanitary Agreement, they are often used strategically to shield domestic industries. However, for a variety of reasons, the EU’s current trade defense instruments may not be sufficient to respond to China’s state-driven market distortions.

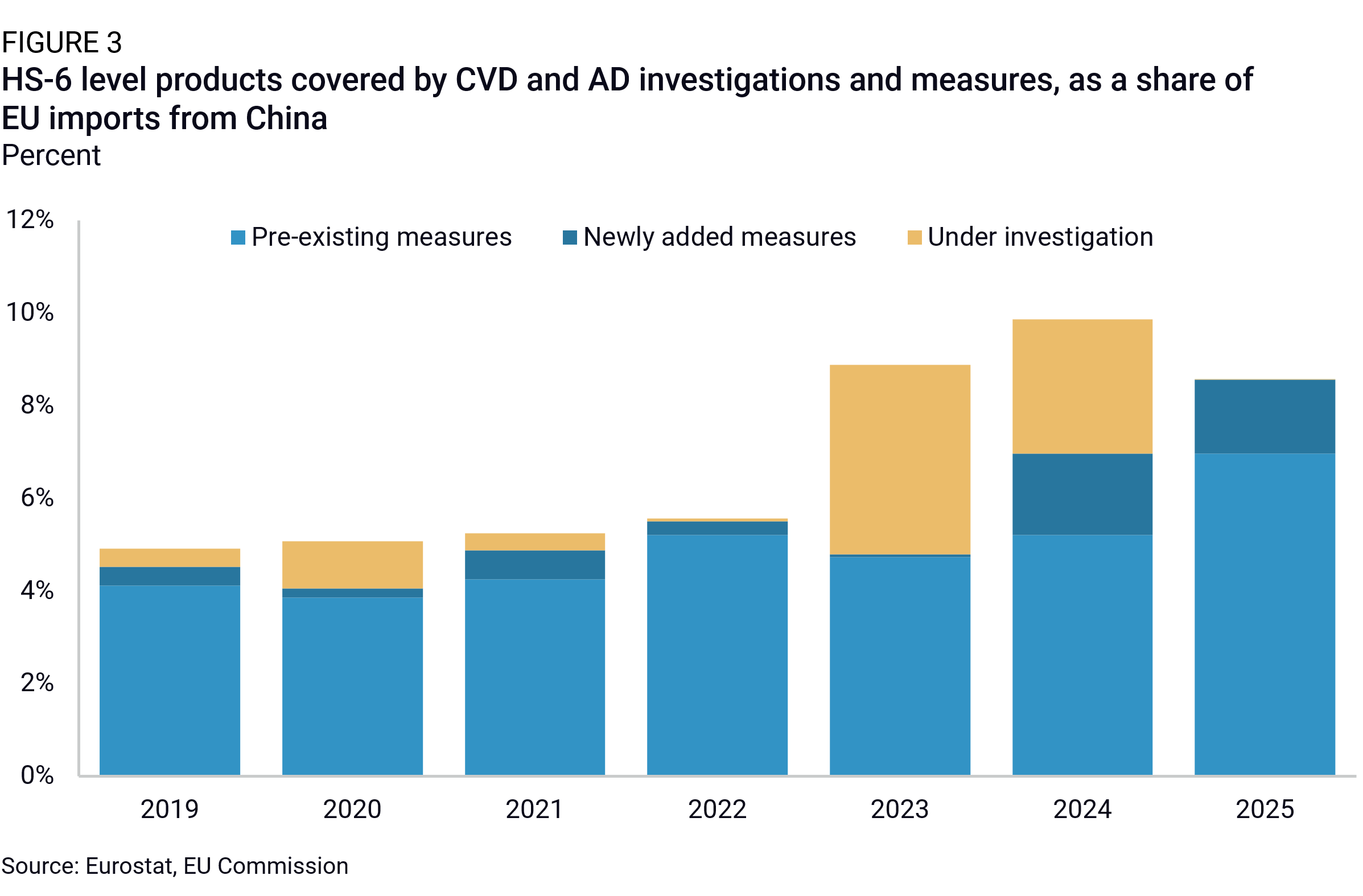

- CVD and AD investigations face limitations due to their lengthy, resource-intensive timelines and narrow product scopes. Despite launching a record 20 AD and CVD cases against China in 2024, the newly launched investigations addressed only about 1.7% of total EU imports from China (Figure 3). The newly implemented measures (some of which were the result of investigations initiated the previous year) affected at most 1.8% of EU imports from China, bringing the total share of products impacted by such measures in 2024 to 8.6%. These estimates may be somewhat inflated, as CVD and AD investigations are based on tariff lines at the HS-8 level, while trade data is publicly available only at the HS-6 level. But even with this inflated estimate, the measures clearly still leave many industries unprotected. Indeed, HS-6 product categories where the EU experienced a significant import surge from China (more than 25% increase in import volume in the past two years) accounted for 28% of imports. Besides, ramping up protection through such investigations more rapidly in the years to come will be challenging given limited resources at the European Commission.

- Safeguard measures offer a broader legal option to address the challenge of rising imports driven by overcapacity. Unlike AD and CVD cases, safeguards can apply to entire sectors rather than specific products, making them a potentially powerful tool. However, the EU has only rarely used them. This is partly because safeguards must be country-agnostic. While this helps prevent trade rerouting, it also risks impacting and alienating other trade partners, making their application politically sensitive. Besides, as with the CVD and AD procedure, safeguards require a lengthy investigation to show that rapidly rising imports threaten to cause or are causing injury to domestic industries. Lastly, the jurisdiction imposing safeguards must offer adequate compensation to the exporting economies affected by the measure through tariff concessions or other trade benefits of equivalent value, making it cumbersome to use.

- The FSR and IPI provide additional ways to counter China’s trade distortions, but their impact is inherently limited as they focus primarily on public procurement. This area represents only a small fraction of the overall market in industries like automotives or chemicals, making it irrelevant in addressing distortions arising from rapid increases in imports.

- Non-tariff barriers are somewhat less constrained than traditional trade defense measures, because they don’t require a legal investigation under the WTO framework. The EU already uses cybersecurity rules (the 5G toolbox), environmental rules (the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism), as well as local content requirements and resilience rules for procurement and industrial policy funding (such as those established under the NZIA and mentioned in the recent Clean Industrial Deal). Other measures are under discussion, such as cybersecurity standards for connected vehicles and wind equipment. To remain compliant with WTO rules, these non-tariff barriers must be applied in a non-discriminatory manner. However, resilience and cybersecurity criteria can be strategically designed to address specific risks—effectively targeting imports from China given the high dependency on Chinese supply chains, and concerns about potential threats arising from Chinese state-directed cybersecurity attacks. That said, increasing the use of these measures to shield the EU from Chinese trade distortions, rather than for their stated purposes, risks undermining the clarity and coherence of the EU’s trade stance. Over time, this could further undermine the credibility of the rules-based trading system and invite challenges or retaliatory measures.

Going systemic

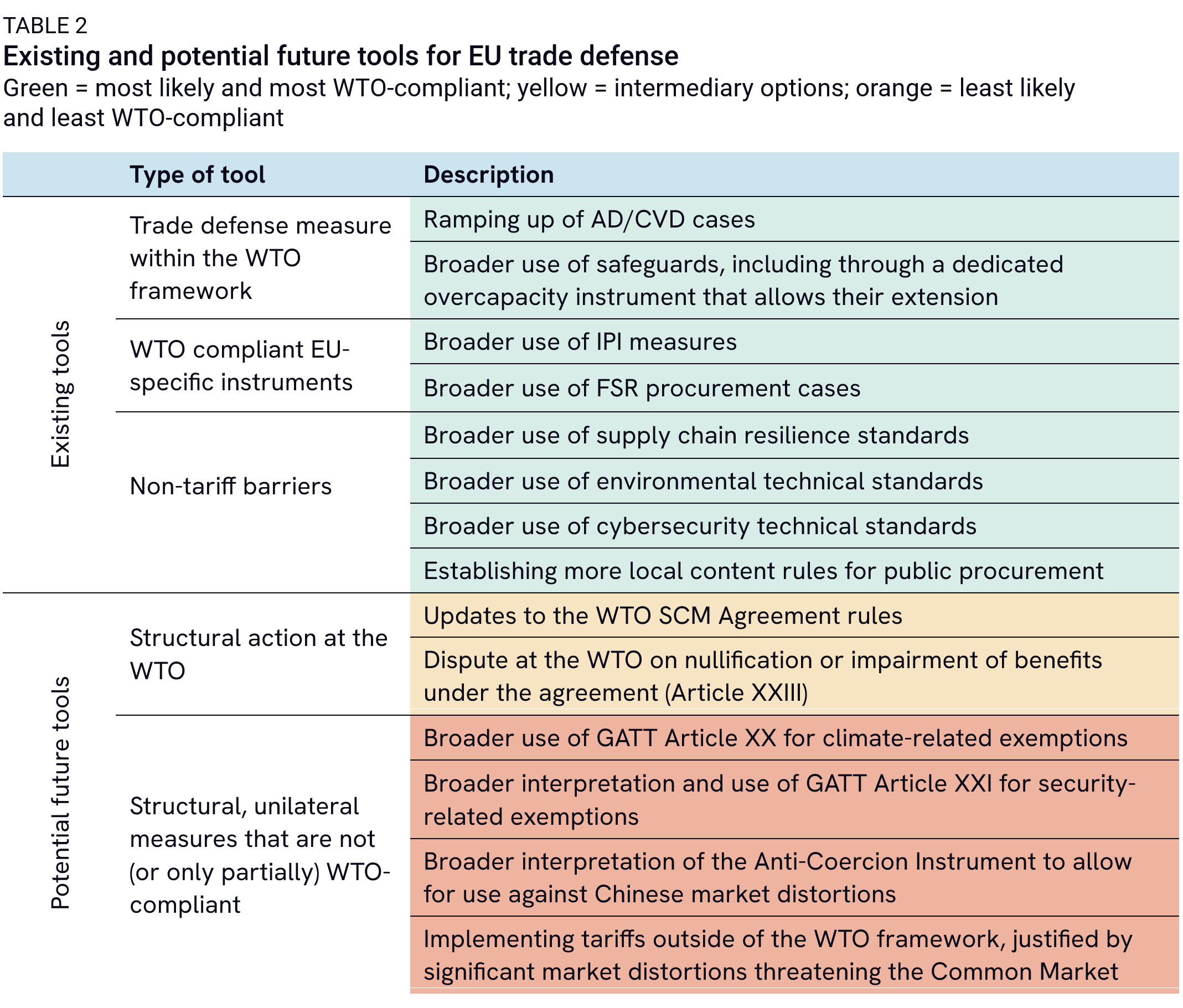

Effectively countering the surge of cheap imports from China will likely require the EU to expand the use of existing trade defense measures—something it has, to a large extent, already started doing. However, given the constraints of the current legal options, Europe could consider a more structural approach. Both the existing tools and more structural approaches can be categorized by how likely and WTO-compliant they are (Table 2).

The first approach—expanding the use of existing trade defense measures—could involve launching more AD and CVD investigations, as well as broadening the scope of products covered within each case. Crucially, it could also mean a more active use of safeguard measures. So far, the EU has only implemented safeguards in the steel sector, following the US Section 232 tariffs under the Trump administration. But the US announcement of Section 232 tariffs on automotive imports in March 2025 (and likelihood of more tariffs in the months to come) could provide a political and legal hook for the EU to expand its use of safeguards across more sectors. This may also prompt the EU to create a dedicated instrument to extend safeguard measures beyond their original timeline—a move that could be particularly relevant for steel, where safeguards are set to expire in June 2026.

This approach could include greater deployment of the EU’s newer tools, such as the FSR and the still-untested IPI. In addition, the EU could intensify its use of technical standards and “non-price criteria” with the goal of shaping market access wherever feasible.

A second possibility would be for Europe to take a more systematic set of actions within the WTO. This could take two forms:

- Pushing for reform of the WTO’s Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement) to better capture the full scope of China’s distortive industrial policies: This would face strong opposition from China and other member countries. Reaching a consensus, if achievable at all, could take years.

- Raising a dispute based on Article XXIII of the GATT: This allows a WTO member to bring a complaint if another member has violated a GATT rule, or if the actions of that other member, even if technically legal, nullify or impair the benefits the complaining country expected to get under the agreement. The EU could argue that China’s industrial policies and self-sufficiency push, while not explicitly breaching WTO rules, nullify or impair the expected trade benefits for WTO members by reducing their export opportunities. If the complaint is upheld, the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Body may authorize retaliation or compensation.2 While powerful, this mechanism would require the EU to launch a lengthy dispute settlement process, which usually takes years to resolve and requires extensive legal and economic evidence, making this a long, uncertain, and resource-intensive process.

The options discussed above are unlikely to provide near-term relief from acute import surges and trade rerouting challenges expected in 2025 and 2026, but could play an important role in the medium to long term, laying the legal and institutional groundwork for a more sustainable trade relationship with China over the next three to five years.

A third possibility would be for Europe to turn to stronger, structural measures. But these would not be compliant, or only partially compliant, with WTO rules.

- One option would be to use the environmental exception provisioned under GATT Article XX to justify restrictions on goods linked to high carbon emissions, pollution, or unsustainable practices—particularly in sectors where Chinese imports are seen as undermining the EU’s environmental and climate goals. This legal route carries diplomatic and reputational risks, however, especially in the Global South. Such rules could alienate emerging economies, many of which are key to the EU’s diversification strategy and may view such actions as out of touch with broader global development concerns.

- A second option would be to reinterpret and expand the use of Article XXI’s national security exemptions to justify trade restrictions based on economic security concerns. The EU could, for example, designate China as a systemic security risk, which would justify broader market restrictions to address economic and strategic vulnerabilities. That broad interpretation would likely be challenged by China under the WTO dispute settlement system but would allow the EU to act quickly in the meantime. In practice, this could involve restricting public procurement, imposing licensing requirements, or banning imports of certain goods linked to critical supply chains.

- A third and equally radical option would be to invoke the Anti-Coercion Instrument against China, broadening the interpretation of economic coercion to justify stronger countermeasures in response to China’s industrial policies and state-driven overcapacity. This option is also politically challenging, as it requires a qualified majority in the Council of the European Union—giving member states the opportunity to block it and potentially exposing them to pressure from China.

- A last option would be to invoke the WTO’s inability to address China’s systemic, opaque, and wide-ranging market distortions to justify country-specific tariffs outside of the WTO framework. This would effectively mirror the approach taken by the United States under Section 301.

All four options would be politically sensitive and would require a level of EU member state coordination that is unlikely to materialize. Importantly, while these options may not demand lengthy investigative procedures, they would still require substantial time and resources to assess and justify their economic trade-offs and implications, to design, and to implement. However, they would offer greater clarity, both domestically and internationally, by openly recognizing the WTO’s limitations in addressing structural issues like overcapacity, rather than forcing existing legal instruments to serve purposes they were not designed for.

Navigating a fragmenting multilateral trading system

The recently published Clean Industrial Deal and the Industrial Action Plan for the Automotive Sector signal that the EU is preparing to use the full range of tools at its disposal—including some that do not yet exist—to respond to the growing challenges posed by Chinese industrial overcapacity and global trade distortions. This includes a more assertive use of trade defense instruments, such as initiating more ex officio anti-dumping and anti-subsidy investigations, following through on the cybersecurity risk reviews of connected vehicles and wind under the NIS2 Directive, tightening rules of origin and action to prevent Chinese firms from bypassing duties, and creatively invoking GATT Article XX (General Exceptions) to justify joint venture or local content requirements. Together, these actions signal not only a ramping up of trade barriers in response to the Chinese challenge, but also a parallel intensification of industrial policy and state support aimed at shoring up the competitiveness and resilience of Europe’s own industrial base.

More broadly, the future of the rules-based trading system and multilateralism is also at stake. The WTO risks losing credibility as more countries—and the EU—resort to measures that are WTO-compliant in form but not in spirit, eroding trust in the system. The US’s growing reliance on bilateral or plurilateral trade deals—which are often not fully compliant with WTO rules—further undermines the multilateral framework and adds to the strain. As outlined in a recent report, there is also a broader recognition that the rules-based trading system may require reform to address emerging structural challenges. In this context, the EU—traditionally a strong supporter of the WTO and multilateral trade governance—will be forced to balance domestic policy objectives against a push for international competitiveness, and its engagement with global trade institutions.

Footnotes

Note that while the EU has only used safeguards once (on steel) and CVD cases remain relatively rare, AD investigations are widely used in Brussels. This preference is driven by two factors. First, AD investigations require a lower burden of proof, and a less complex investigative process compared to CVD cases. Second, in cases involving China, the EU can apply its “significant market distortions” (SMD) methodology, which allows the calculation of dumped prices using alternative benchmarks rather than relying on China’s domestic prices. This often results in significantly higher duties than those imposed through CVDs.

Note that while the WTO Appellate Body remains effectively inoperable, the EU could still pursue these cases using the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA)—a temporary alternative system created by the EU and other WTO members to maintain dispute resolution in the absence of a functioning appellate body.