Rhodium Climate Outlook: Setting the Stage for Ambitious 2035 NDCs

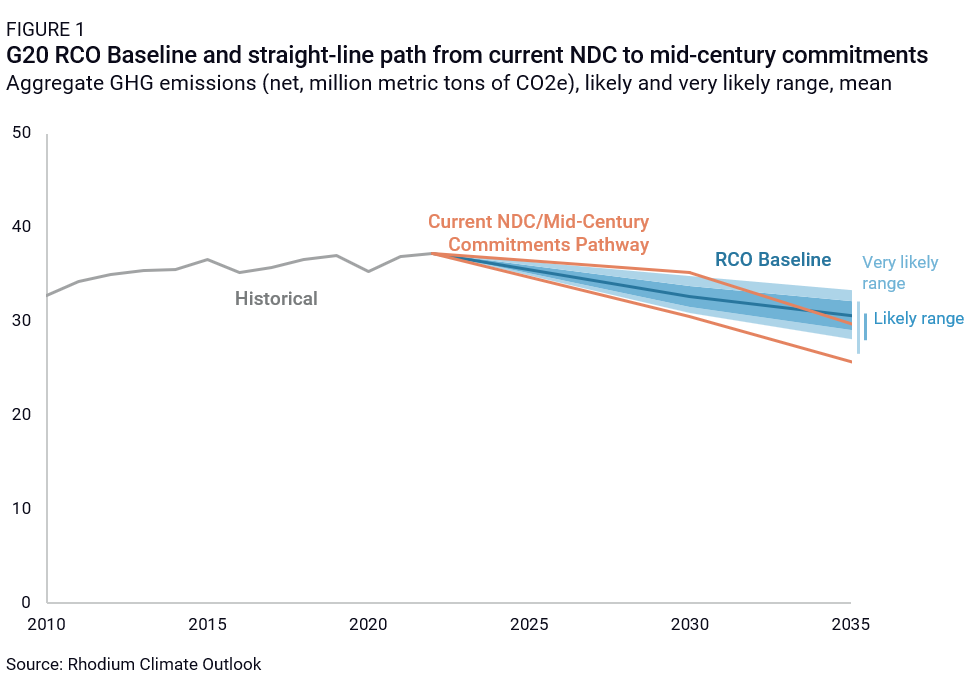

We set a foundation for 2035 expectations for G20 economies by comparing projected emissions under today’s baseline with prospective reductions that would be required to stay on a straight-line path from their 2030 NDCs to their mid-century targets.

Early next year, countries will unveil new 2035 emission targets, marking a critical juncture for the Paris Agreement’s nationally determined contribution (NDC) five-year cycle. The 2035 NDCs will shape global climate ambition over the next decade and serve as an important stepping stone to achieving net-zero emissions around mid-century. There is no science-based rulebook for determining whether an individual country’s proposed NDC is “Paris-aligned.” The Paris Agreement empowers nationally determined targets guided by the Global Stocktake, which encouraged parties to set economy-wide targets aligned with mid-century strategies and goals. Observers often look to the world’s largest economies and biggest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitters—many of which are included in the Group of 20 (G20)—to set expectations for what ambitious NDCs may look like. In this note, we set a foundation for 2035 expectations for G20 economies by comparing projected emissions under today’s baseline with prospective reductions that would be required to stay on a straight-line path from their 2030 NDCs to their nationally determined mid-century targets.

Looking beyond the G20, if all countries set 2035 NDCs that keep them on the path from their 2030 NDC to their current mid-century targets, it could have a transformative impact, raising the likelihood of limiting global mean temperature rise to below 2°C from less than 7% to nearly 68%. If all the world’s countries commit to net-zero by 2070 and expand their existing carbon-neutrality targets to cover all GHGs, we find that likelihood soars to 96%, making the 1.5°C target attainable (67% chance) by the century’s end.

Setting the stage for ambitious 2035 NDCs

The Paris Agreement explicitly allows countries to set their own NDCs every five years. There is no explicit measure or authority that assesses whether individual countries’ NDCs are sufficiently ambitious. The Global Stocktake, however, provides an assessment of global progress on limiting warming to well below 2°C that acts as a feedback mechanism to inform the NDC process. The conclusion of the first Global Stocktake at COP28 in Dubai urged parties to submit economy-wide emission reduction targets aligned with limiting global warming to 1.5°C and to “align their next nationally determined contributions with long-term low greenhouse gas emission development strategies.”

As countries prepare to announce their 2035 NDCs in a few months, understanding each country’s trajectory under existing policy and energy market conditions is critical to assessing future ambitions. However, methodologically consistent, economy-wide emissions baselines are lacking, making it challenging to gauge the ambition of proposed NDCs. In the last round of NDCs, limited transparency on economic growth—a highly uncertain variable and a key driver of GHG emissions projections—and other key assumptions created barriers to accurately assessing the ambition of proposed 2030 NDCs.

The Rhodium Climate Outlook (RCO) aims to bridge this gap by offering methodologically consistent, economy-wide emissions projections for all G20 economies under a range of potential economic and energy market futures. This includes probabilistic GDP projections, which are essential for understanding variability in future GHG emissions. Unlike other sources of emissions projections, which often assume a single deterministic pathway for GDP, the RCO considers a full range of potential economic growth outcomes.

To set expectations for 2035 NDCs, we examine G20 economies’ 2030 NDCs and the likelihood of achieving those targets below. We then assess the outlook for their 2035 emissions and compare them to a straight-line trajectory from their 2030 NDCs to their nationally determined mid-century net-zero commitments.

G20 progress toward 2030 NDCs

Among the G20 economies, there are three primary NDC types for the period ending in 2030:

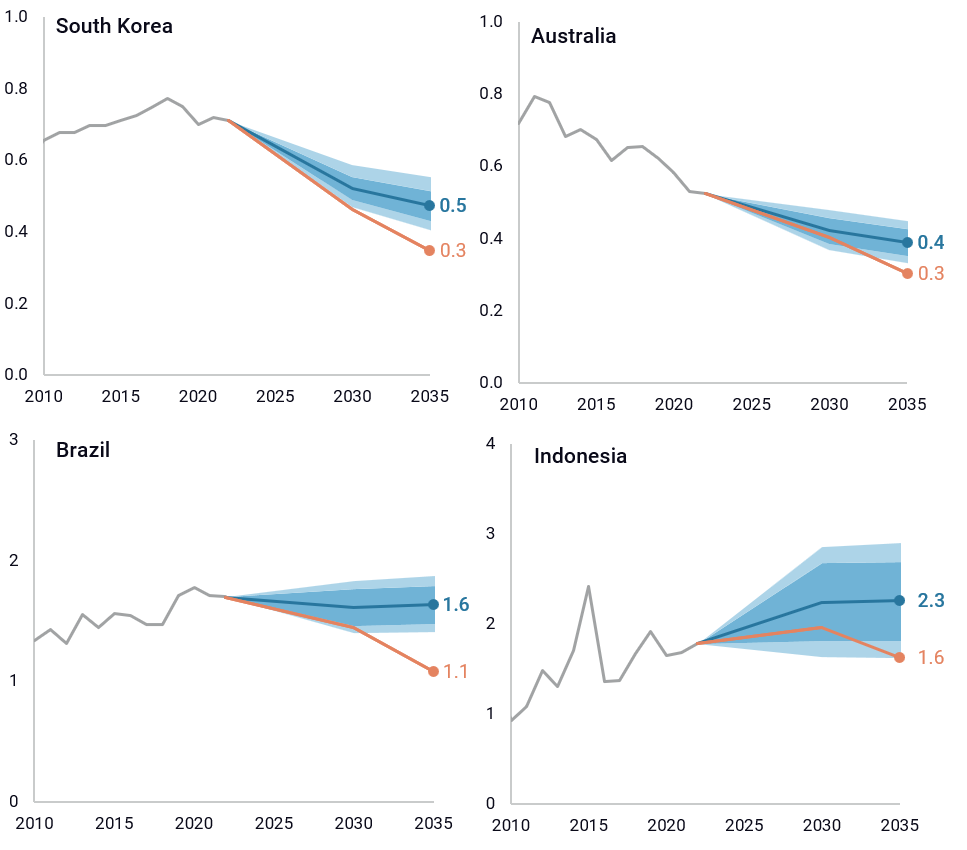

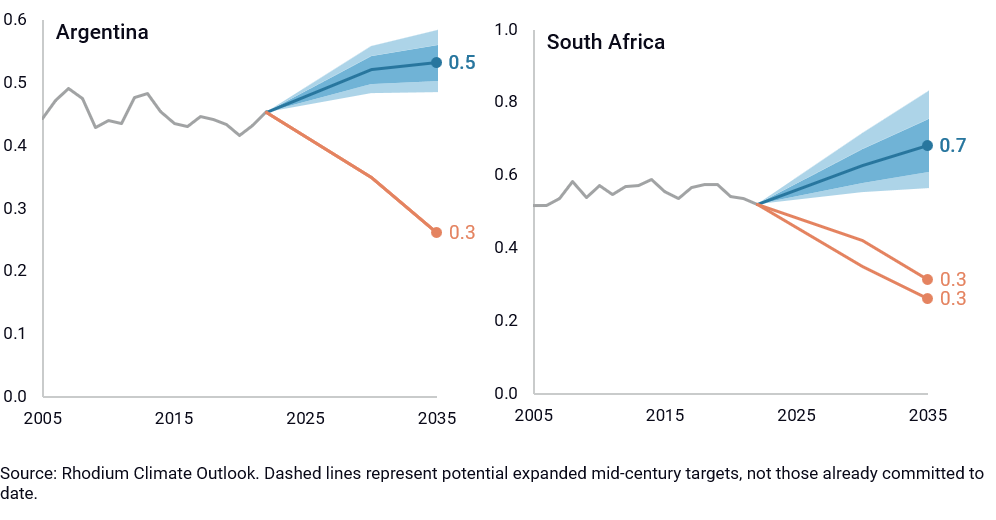

- Absolute, economy-wide GHG targets: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, EU, Japan, South Korea, Russia, South Africa, UK, US

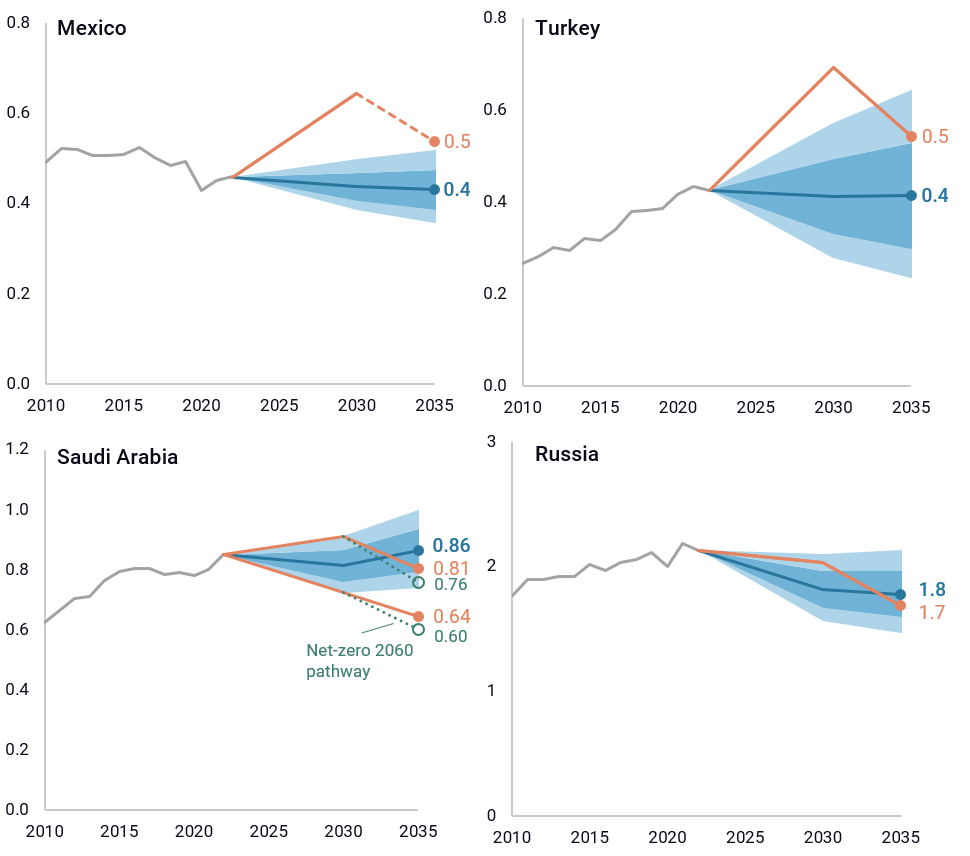

- Reductions from a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario: Indonesia, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Turkey

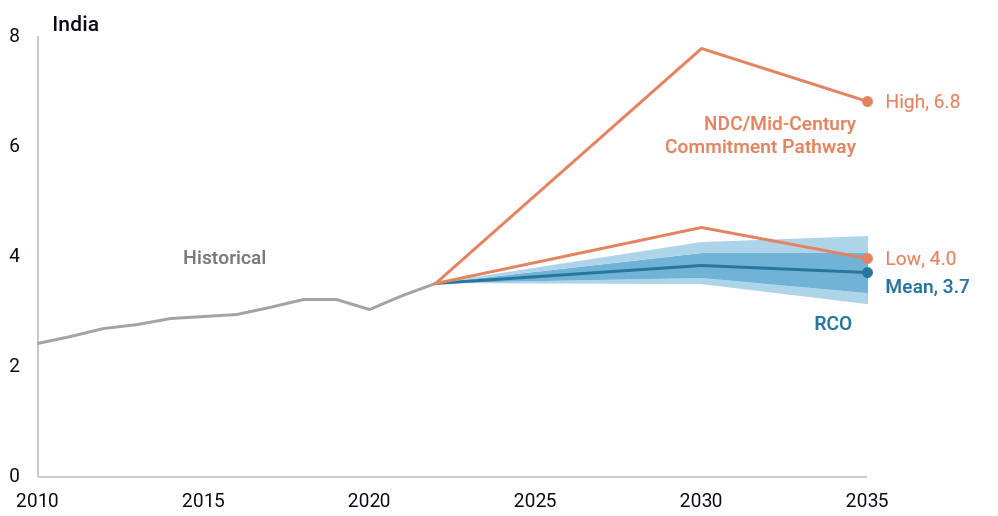

- Emission intensity (CO2 per GDP) targets and non-fossil energy shares: China, India

For this analysis, we model the emissions implications of G20 economies meeting current 2030 NDCs, focusing only on unconditional NDCs. We find that five countries—Australia, China, Indonesia, Japan, and Russia—are on track today to meet their 2030 NDCs. Brazil’s 2030 NDC is marginally feasible, with a low probability of less than 17% at the far edge of the RCO Baseline likely range. China’s outlook has evolved considerably since its 2030 NDC was set, with emissions likely on track to decline 11-19% below 2022 peak levels by 2030, keeping them in line to meet the 60-65% reduction in carbon intensity and 25% non-fossil energy consumption targets.

India, Mexico, and Turkey are very likely to over-deliver on their 2030 NDCs given their current trajectories. Mexico and Turkey adopted BAU targets in 2020 that overestimated the potential for emissions growth. India’s economy-wide emissions intensity target of 45% below 2005 levels is highly sensitive to economic growth through 2030. Between 2005 and today, India’s GHG emissions have doubled. Still, its GDP increased nearly four-fold, putting India on track to reduce its emissions intensity by about half and achieve its 45% target. We don’t yet know how much India’s economy will grow between now and 2030, though over-achievement is likely, with a 90% probability in our RCO Baseline.

Seven countries are currently off track to meet their 2030 NDCs, despite emissions trending downward over the rest of the decade: Argentina, Canada, the EU-27, South Korea, South Africa, the UK, and the US. However, Argentina and South Africa’s emissions are trending in the wrong direction, likely rising from today’s levels.

Saudi Arabia lacks clarity about its NDC, so we assume emissions follow the RCO Baseline range through 2030. The country’s updated NDC specifies a target of reducing emissions by 278 million metric tons of CO2e below two potential dynamic BAU scenarios, about which they provide no information.

Overall, most G20 economies are on track or within striking distance of meeting their 2030 NDCs (Figure 1). As a group, G20 economies are likely on track to decrease their GHG emissions by 9-15% below 2019 levels by 2030, absent a significant acceleration of climate and clean energy policy. If all G20 economies met their current 2030 NDC commitments and none overachieved them, the G20 would decrease emissions by only 7-14% below 2019 levels by 2030. That’s less than they are likely on track for today.

Outlook for individual G20 economies through 2035

As part of the Paris Agreement, countries also agreed to establish “long-term low greenhouse gas emission development strategies,” commonly referred to as net-zero targets. To date, countries representing 88% of global emissions have net-zero or carbon neutrality targets formalized in law, policy documents, or public announcements by the head of state. All G20 countries except Mexico have adopted or announced net-zero targets within the 2050-2070 timeframe. China and Saudi Arabia’s mid-century targets cover only carbon dioxide (CO2), rather than all greenhouse gases.

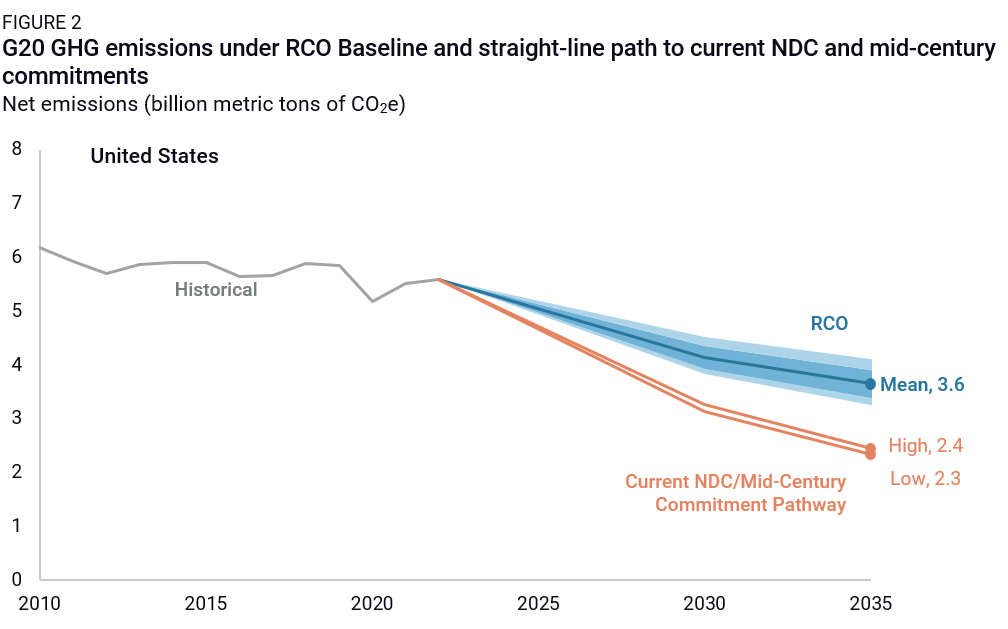

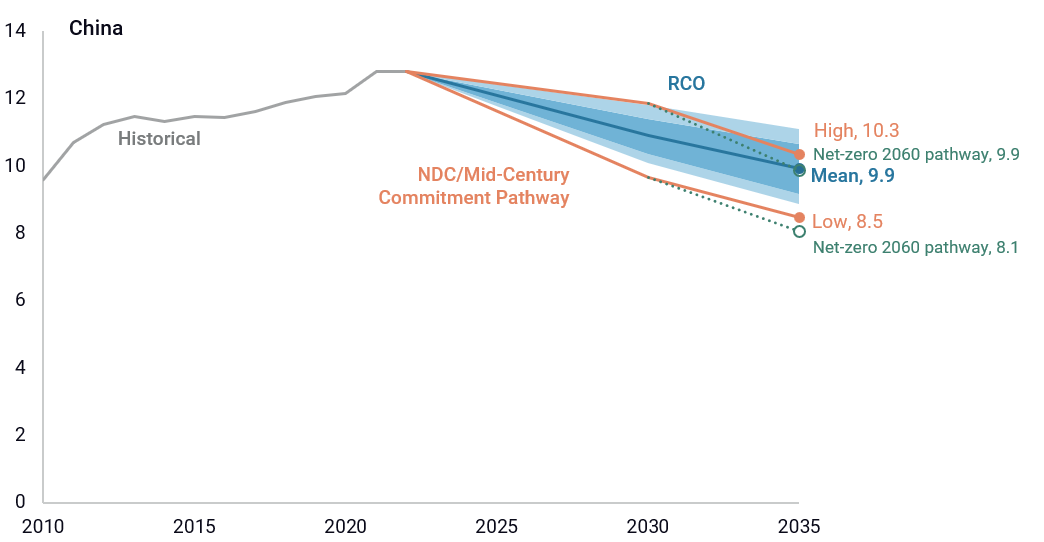

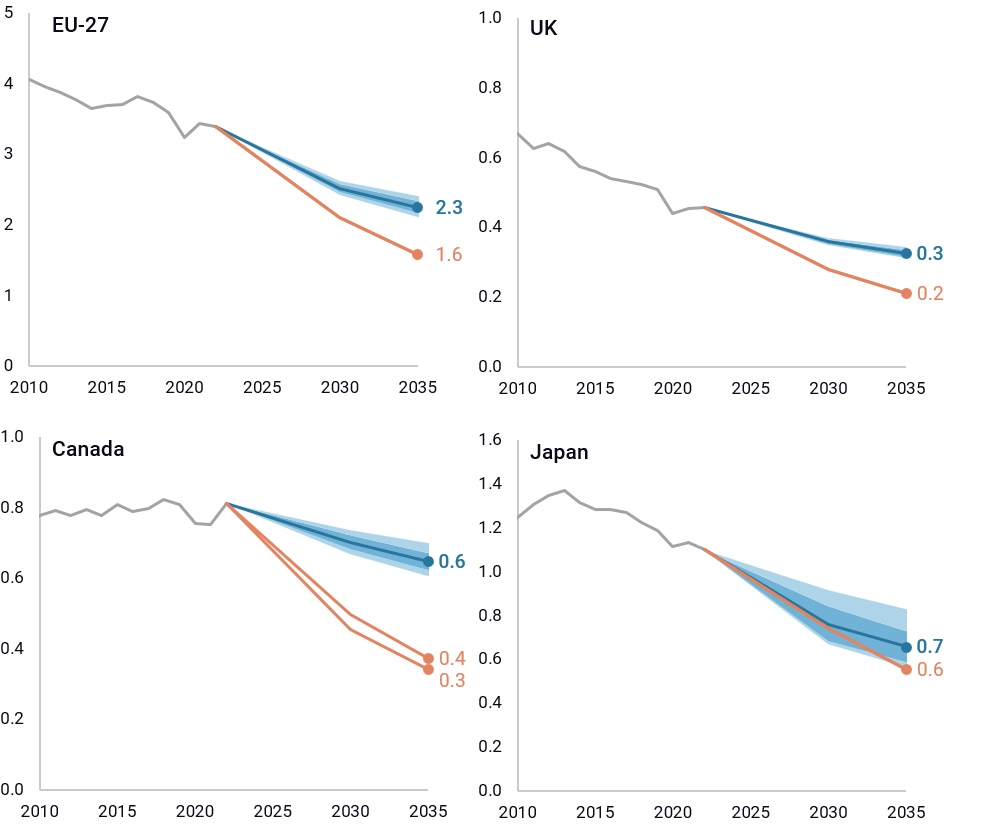

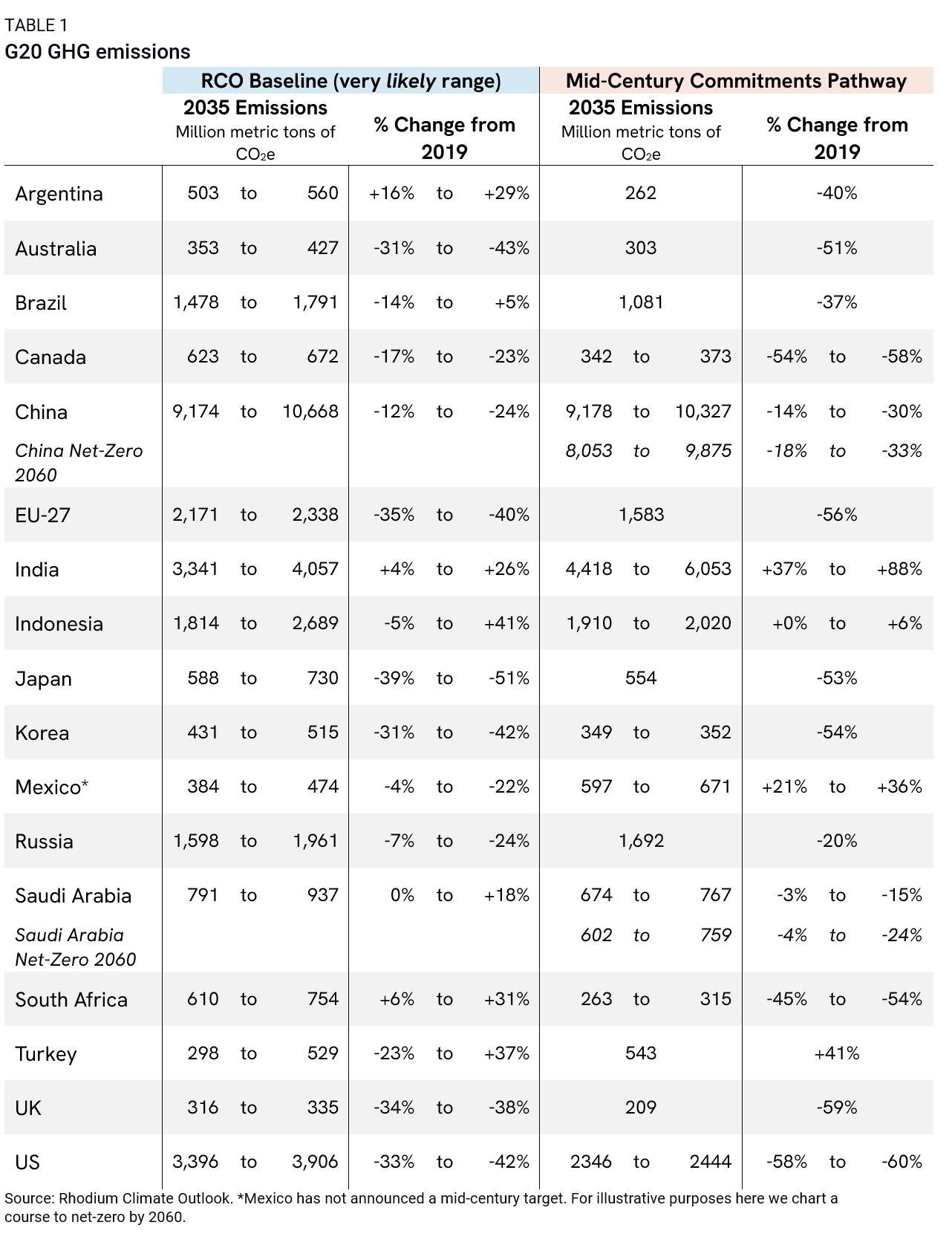

To set a foundation for 2035 expectations, we assess projected G20 emissions in 2035 under our RCO Baseline and compare it to a straight-line path from 2030 NDCs to mid-century targets (e.g., each country’s Current Mid-Century Commitment scenario) (Figure 2).1 For China and Saudi Arabia, which have 2060 carbon neutrality targets, we also include a look at an alternative straight-line path from 2030 NDCs to net-zero GHGs in 2060 (Expanded Net Zero pathway). If all G20 economies align their 2035 NDCs with these trajectories and Mexico adopts a 2060 net-zero target, G20 emissions would be on track to decrease by 21-28% below 2019 levels by 2035.

We report all projected emissions levels in 2035 under our RCO Baseline’s very likely range (90% probability of occurring) and under a pathway to mid-century commitments, as well as the change from 2019 levels in Table 1 at the end of this note. This data is also available in the ClimateDeck.

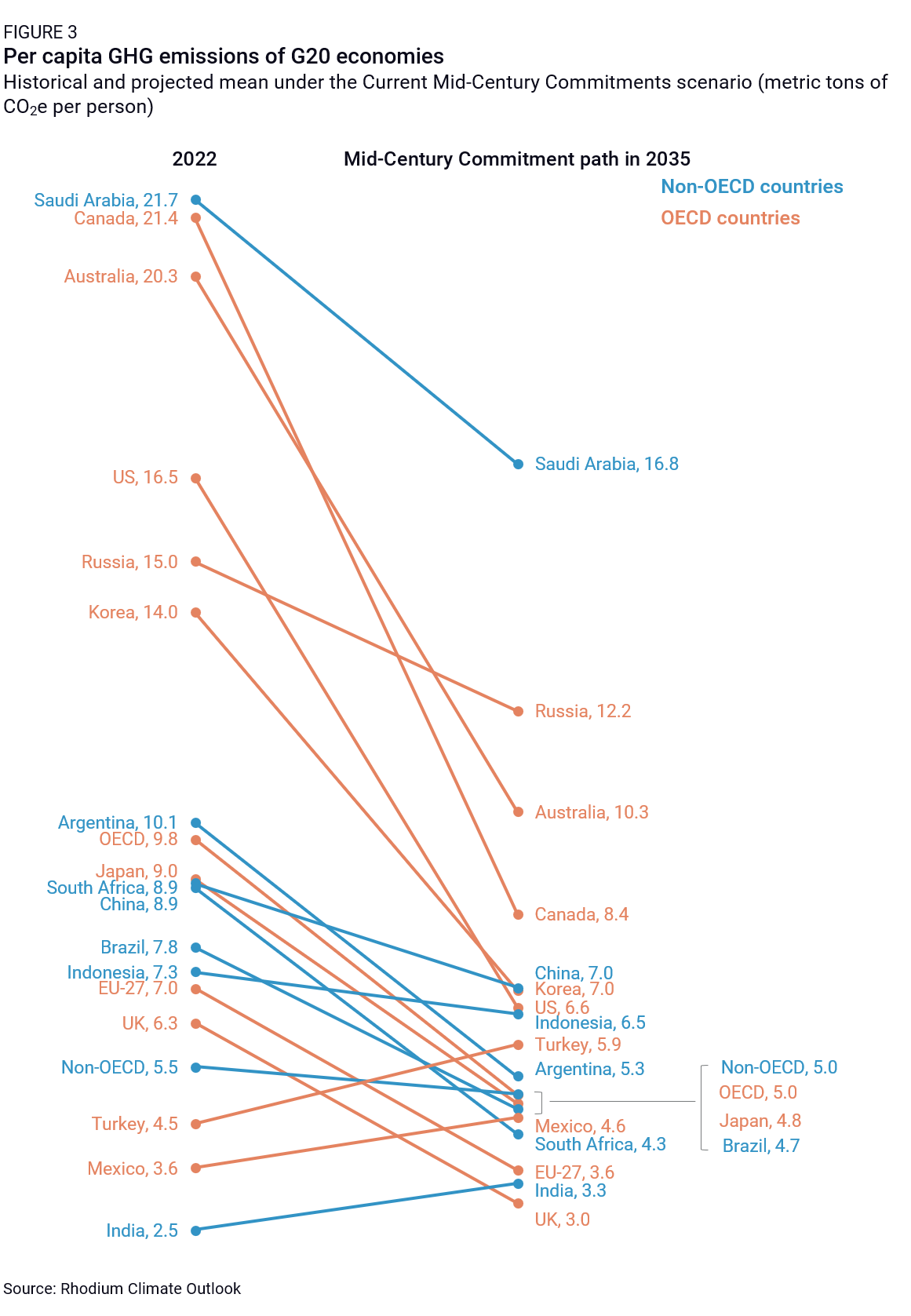

Across G20 economies, per capita emissions converge significantly by 2035

Aligning 2035 NDCs with existing net-zero goals would drive convergence in per capita emissions across G20 economies (Figure 3). Most G20 economies would experience a significant decline in per capita emissions, with Australia, Canada, the EU-27, South Korea, the US, and the UK halving their levels in just over a decade. The exceptions are India, Mexico, and Turkey. Average Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) per capita emissions would drop by nearly half from 9.8 tons to 5.0 by 2035, converging with non-OECD levels, which would decline slightly from 5.5 tons per capita today.

If G20 economies adopted 2035 NDCs aligned with a straight line to their net zero targets, per capita emissions would converge at 3-7 tons across most economies. China, Indonesia, South Korea, and the US would level at 6.5-7 tons, while Brazil, Japan, Mexico, and South Africa would converge at 4.3-4.8 tons. Per capita emissions in the EU and UK drop from around 6 tons per capita to around 3, meeting India, which rises from 2.5 tons today.

Global emissions and temperature rise outlooks under more ambitious scenarios

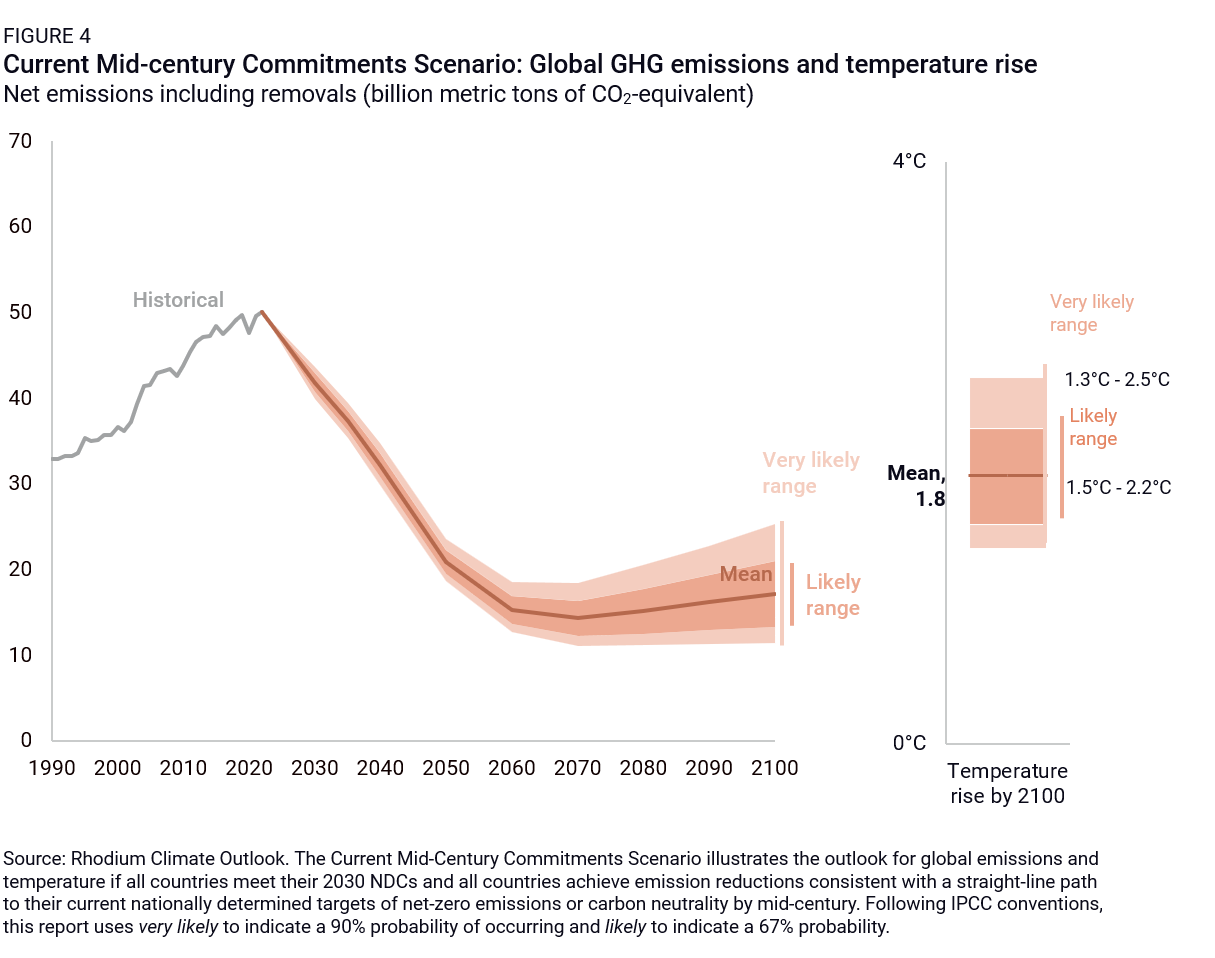

The G20 sets a powerful example for ambitious NDCs, but they are not the only players. To illustrate that global impact requires broader action, we estimate global emissions and end-of-century temperature rise if all countries meet their 2030 NDCs and set 2035 and subsequent NDCs on a straight-line path to their stated target of net-zero emissions or carbon neutrality by mid-century. Under this global Current Mid-Century Commitment Scenario, global emissions likely drop to 36-38 gigatons by 2035 (23-28% below 2019 levels) and 18-21 gigatons by 2050 (58-63% below 2019 levels) (Figure 4).

By 2070, global emissions bottom out at an average of 12 gigatons of CO2e (likely range of 10-14 gigatons), largely from countries without mid-century net-zero targets or with CO2-only mid-century targets (i.e., China and Saudi Arabia). Absent new or updated net-zero commitments, global emissions likely plateau at 11-18 gigatons through the century’s end. This scenario increases the odds of keeping global mean temperature rise below 2°C from less than 7% to 68%, with the world very likely on track to see 1.3-2.5°C increase by 2100 and likely on track for 1.5-2.2°C (1.8°C on average) above pre-industrial levels.

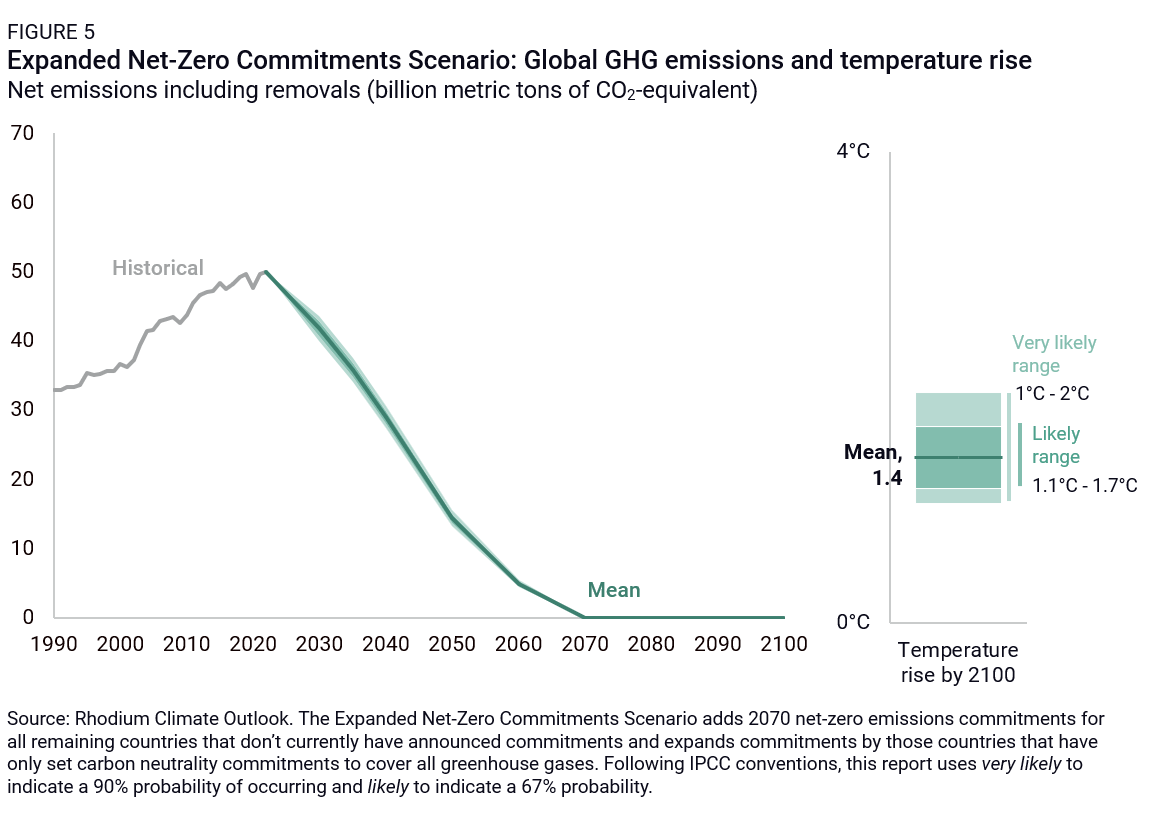

In our Expanded Net-Zero Commitments Scenario, China and Saudia Arabia adopt net-zero GHG by 2060, and all remaining countries that have yet to announce mid-century targets adopt 2070 net-zero targets (following the path of India). Under this scenario, global emissions likely drop to 35-37 gigatons by 2035 (26-30% below 2019 levels), and residual emissions drop to 13-15 gigatons by 2050 (70-74% below 2019 levels), reaching five gigatons by 2060 and zero by 2070 (Figure 5). This scenario nearly ensures warming remains below 2°C (96% probability) and puts the 1.5°C end of century goal within reach (62% probability) with the world likely on track for 1.1-1.7°C by 2100 with an average overshoot of 1.7°C in 2050 (1.5 to 1.9°C likely range), illustrating the significance of getting all countries to net-zero emissions before 2070.

Footnotes

In the absence of an announced mid-century target by Mexico, we charted an illustrative path from Mexico’s 2030 NDC to net-zero by 2060.