Has the Supreme Court Blocked the Path to the 2030 Climate Target?

In West Virginia v. EPA, the US Supreme Court constrained one of the most powerful regulatory tools for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In light of the ruling, does the US still have the ability to achieve its 2030 climate target?

Yesterday, in a 6-to-3 decision in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Supreme Court ruled that EPA does not have the authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate carbon emissions from the power sector through a system-wide mandate to shift from coal-fired power generation toward cleaner sources. The ruling constrains one of the most powerful regulatory tools from the executive branch’s toolbox of regulations to help reduce US greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In light of the decision and amid stalled climate action in Congress, many are now questioning what climate policy options are still left on the table, and whether the US still has the ability to achieve its 2030 climate target of reducing emissions by 50-52% below 2005 levels.

We find that the Supreme Court’s ruling does not change the game by much. Last fall, Rhodium Group published Pathways to Paris, a comprehensive assessment of a portfolio of federal legislation, regulations, and other actions across all levels of government, which together could put the 2030 target within reach. In this note, we revisit that list of actions and assess the implications of the Supreme Court ruling for the pathway to the 2030 climate target. We find that while the ruling certainly makes the pathway rockier, it hasn’t necessarily put the target out of reach. The silver lining of the ruling is that it has cleared up ambiguities that have plagued power sector GHG emissions regulations for a decade. Going forward, EPA may have more legal certainty and can still leverage other regulatory tools that could drive significant emissions cuts in the power sector and other sectors. However, EPA needs to move fast in order to help achieve the target. Without swift progress on all fronts—including in Congress and across other levels of government—the 2030 target is in jeopardy.

What West Virginia v. EPA does and doesn’t do

The Supreme Court’s 6-3 decision in West Virginia v. EPA rules that EPA does not have the authority under section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act to regulate emissions from the power sector at a system-wide level. While the ruling certainly limits regulatory pathways to reducing emissions and removes one of the more efficient and low-cost regulatory options, the decision was also not the worst-case scenario for EPA’s ability to regulate emissions that many had feared. The ruling does not entirely revoke EPA’s authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, nor does it state that EPA can’t regulate GHG emissions from power plants. EPA still has the authority to regulate emissions at the point source or individual power plant level—what’s often referred to as “inside the fence line” of the facility, as opposed to “outside the fence line” or a systems-based approach, which is now off-limits under the ruling.

One consolation from the ruling is that it potentially clears up legal ambiguities that have plagued power sector emissions regulations for a decade. EPA may have more certainty about the rules of the regulatory road and how to regulate emissions from point sources. The Supreme Court made it clear that if EPA wants to regulate emissions from point sources, it can only consider emissions-control measures at the source. This is the same approach that EPA has used for an array of other pollutants over the 50+ year history of the Clean Air Act. Indeed, it’s the same approach EPA has used in setting GHG standards for new power plants as well as one of the three building blocks in the Obama EPA’s Clean Power Plan. While the ruling means that some regulatory options are now off-limits, it also means that EPA now knows that it can leverage existing emissions-control technologies to drive significant emissions cuts in the power sector, such as carbon capture and fuel blending. Some of these options may cost more than a system-wide approach and may result in fewer co-benefits like reduced local air pollution, but all of that will depend on how EPA ultimately chooses to exercise its clarified authority and what other conventional pollutant regulations it pursues.

What the ruling means for the 2030 climate target

In light of the ruling, and especially as federal climate legislation is currently stalled in Congress, many are now questioning what regulatory options and other climate policy options are still left on the table, and whether the US still has the ability to achieve its 2030 climate target of reducing emissions by 50-52% below 2005 levels.

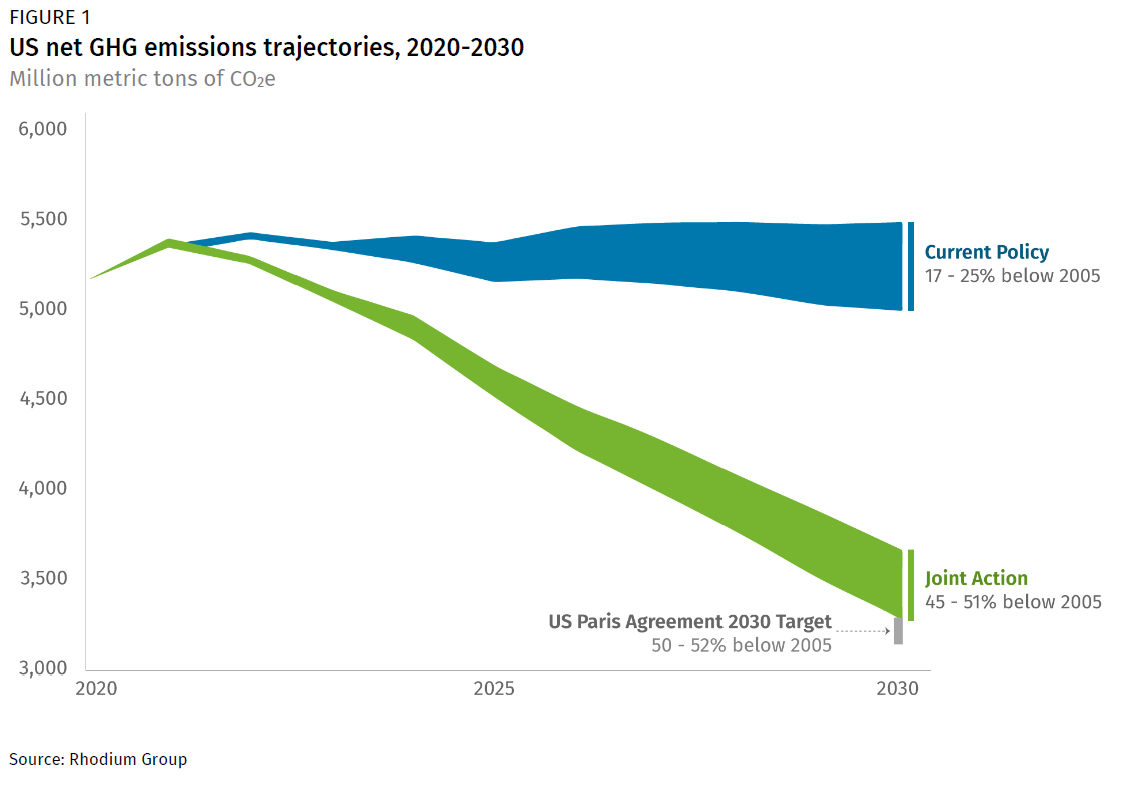

In order to answer those questions, we revisit Pathways to Paris, a comprehensive assessment of a portfolio of policy actions that the US could take to put the 2030 climate target within reach, which we published last fall. We found that without any new climate action, the US is not on track to meet its 2030 target of reducing emissions 50-52% below 2005 levels (Figure 1). With no additional action, at best emissions get halfway to the target—25% below 2005 levels in 2030—but could be as high as 17% below 2005 levels (reflecting the uncertainty around energy prices, technology costs, and carbon removal from natural and working lands). This leaves an emissions gap of 1.7-2.3 billion metric tons between current policy and the 2030 target. To fill that gap, we developed a “joint action” scenario— congressional passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the now-stalled Build Back Better Act, alongside regulations and other executive branch actions and supplemented with subnational action in climate-leader states. All together, this scenario would achieve an emissions reduction of 45-51% below 2005 levels—putting the 2030 target of a 50-52% reduction within reach.

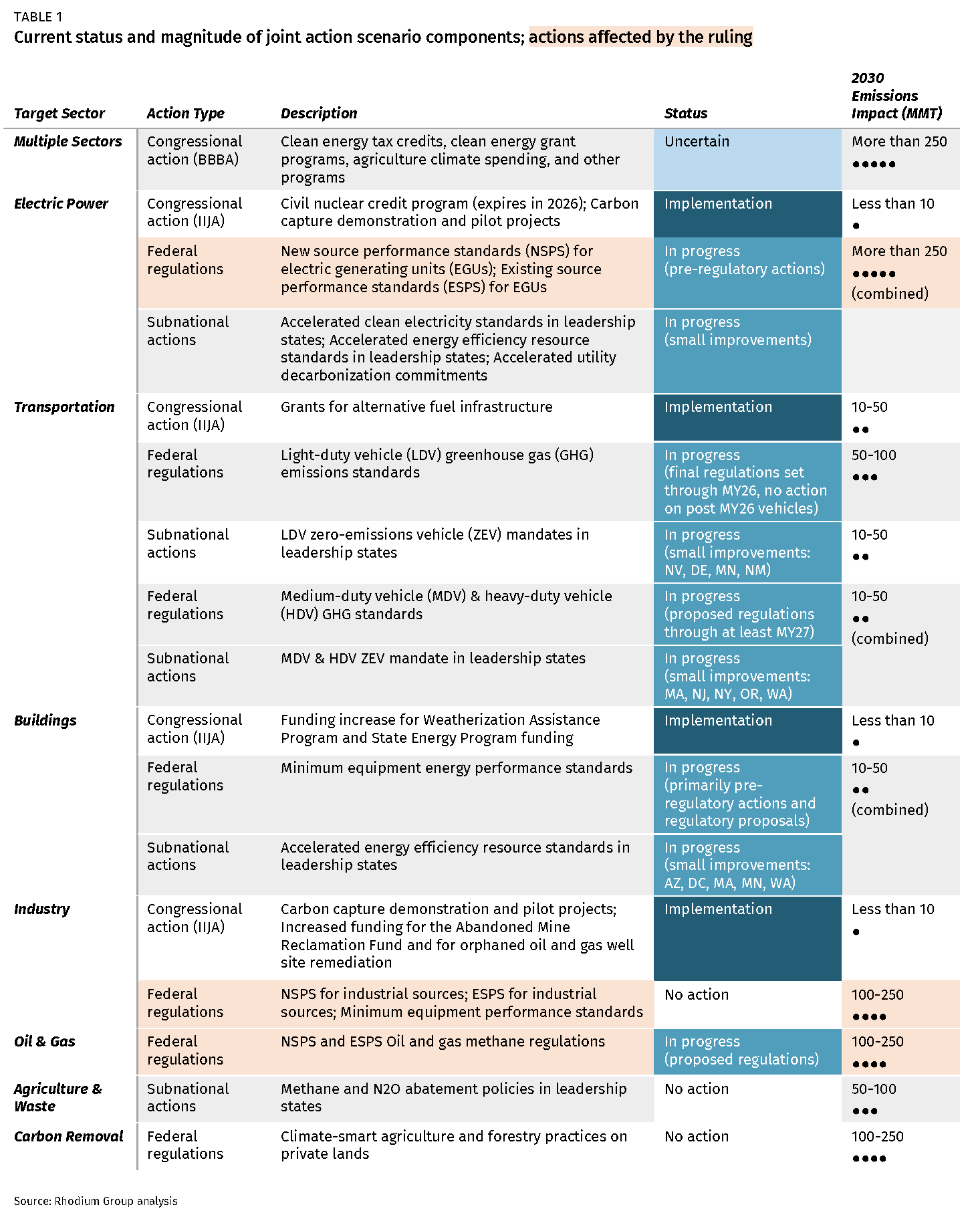

Two weeks ago, we published a progress update on the measures we considered in the joint action scenario. We found that while some movement has occurred on some fronts, most big-ticket items, including major federal regulations like power plant carbon rules and legislation in Congress, have yet to get started or are still under deliberation (Table 1 below).

On the question of the implications of the Supreme Court ruling on that list of measures—when we constructed our joint action scenario, we modeled three actions by the executive branch that rely on section 111 of the Clean Air Act to cut emissions. These are (highlighted in red in Table 1):

- New and existing source performance standards on CO2 for electric power plants (no current progress)

- New and existing source performance standards on CO2 from select large and fast-growing industrial sources (no current progress)

- New and existing source performance standards on methane from oil & gas wells (some progress)

While the West Virginia v. EPA ruling pertained to power plants, the decision applies to all three of the above components of our joint action scenario. However, when we constructed the joint action scenario, we only considered “inside the fence line” controls for methane from oil & gas wells and CO2 from the industrial sources—meaning that the actions we modeled fit within the new legal constraints under the ruling. The Supreme Court affirmed EPA’s authority to regulate these sources and clarified that the approaches already used in EPA’s proposed methane rules and the approach we contemplated for the industrial regulations are legal.

For power plants, we considered an “outside the fence line” standard, which the ruling clearly deems illegal. However, there is no reason why EPA can’t craft new regulations on existing fossil fuel fired power plants using an “inside the fence line” approach that attempts to reach a similar level of ambition as we contemplated in our joint action scenario. Even if they pursue less ambitious GHG standards, they can also pursue more stringent conventional pollutant standards, with a combined impact that is in line with what we modeled previously.

This is the silver lining in the West Virginia v. EPA cloud, because these three measures are some of the highest-impact actions that we assessed in Pathways to Paris. We found that the power plant regulations (combined with subnational actions) could achieve more than 250 million tons of reductions in 2030, while the industrial source and oil & gas well regulations could each achieve 100-250 million tons. It also means that the Supreme Court’s decision in and of itself is unlikely to limit the potential ambition of future EPA regulations, and that it won’t solely jeopardize the US’s ability to achieve the 2030 climate target.

That being said, any action that constrains the ability of the US to tackle climate change is not good. In this instance, EPA now has a narrower set of technologies and actions it can consider when regulating GHGs from existing power plants and other stationary sources. “Inside the fence line” control technologies on which EPA has previously relied in the power sector only go so far, so EPA must go beyond heat rate improvements and the like to truly move the needle on emissions. EPA has less experience with some new control technologies, such as carbon capture or hydrogen blending, and these technologies are more expensive than a more cost-effective “outside the fence line” approach. Some new control technologies may also require additional build-out of infrastructure that have their own costs and may take time to deploy. These factors may add up to bigger political challenges around the total cost of regulations and may face opposition from some stakeholders who have traditionally opposed certain control technologies like carbon capture.

Without swift action, the 2030 climate target is in jeopardy

The West Virginia v. EPA ruling by itself doesn’t put the US’s 2030 climate target in jeopardy, but the pathway to the target certainly isn’t guaranteed. As we wrote in our mid-June progress update, it’s clear that there needs to be swift progress on all fronts of government if the US is going to get on track to achieving the target. This means that Congress, the Biden administration, and states all need to accelerate progress this year towards closing the emissions gap. If any front fails to act, it will be increasingly difficult to see a reasonable path to the 2030 climate target.

While the ruling constrains a powerful regulatory tool, EPA and the executive branch still have other options in their toolbox, ones that now may have more legal certainty. But they need to get moving fast if they’re going to play their part in achieving the target. New regulations proposed this year have a good chance of being finalized outside the Congressional Review Act window, limiting the power of potential future anti-climate presidents and congresses. In addition, it takes time, often more than a year, for rules to be finalized, take effect, and be fully implemented. Given that 2030 is less than eight years away, the sooner that regulations are finalized, the sooner they can have an impact on reducing emissions.

RELATED RESEARCH:

Pathways to Paris: A Policy Assessment of the US 2030 Climate Target, published October 2021

Progress on the Pathway to Paris?, published June 2022