Note

Beijing’s Silence is Deafening

China's economic policymaking process appears broken, or at the very least impaired.

The key question from the Third Plenum is whether Beijing can credibly and coherently message its reform priorities to change China’s economic trajectory in the near future. Resetting expectations is vitally important, but meeting them is harder.

The Third Plenum of the Communist Party’s Central Committee will convene July 15 to 18 to outline a long-term economic reform agenda. The meeting represents an opportunity for Beijing to reset expectations—about the direction of the economy, about the capacity of policymaking, and about the future alignment of China’s economy with the rest of the world—at a time when global pushback against China’s exports of excess capacity is intensifying.

The challenge for Beijing is credibly messaging a new direction in the economy to both domestic and foreign audiences after years of reform and promise fatigue. Costs of adjusting the economy are now far higher than when the last substantive Third Plenum reform agenda was unveiled in 2013, and valuable time has been lost. This note outlines our expectations for what China’s leaders will actually do, against a list of urgently necessary priorities for structural reform.

No one should expect breakthroughs in rebalancing the economy overnight, and the Plenum is not the venue for detailed policy proposals, nor for short-term economic stimulus. The key question is whether Beijing can message its reform priorities—progress toward a unified national market, some fiscal reforms, changes in land quota allocations, reforms to the power system, liberalization of foreign investment in some sectors—as a coherent plan to change China’s economic trajectory in the near future. Resetting expectations is vitally important, but meeting them is a greater challenge.

The 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China will hold its third plenary session from July 15 to 18. Unlike the National People’s Congress which meets every year in March to discuss that year’s economic goals or short-term policy adjustments, Third Plenum meetings discuss longer-term economic reform priorities.

Beijing’s challenges are monumental, both in presentation and substance of reforms. The fundamentals of China’s economy are not nearly as healthy as in 2013. The population is declining, the retirement age is unchanged so the labor force is shrinking quickly, the property bubble has burst, local government debt is crippling fiscal policy, and extensive crackdowns against private sector firms have weakened business confidence. The legacy of China’s zero-COVID policy has weakened the Party’s reputation for technocratic competence both domestically and overseas. The rest of the world is increasingly alarmed that China’s manufacturing-led growth strategy will require far more aggressive trade defenses since there are limited signs China’s domestic demand is expanding to reduce trade imbalances. In the absence of significant structural reforms, much slower long-term economic growth looms.

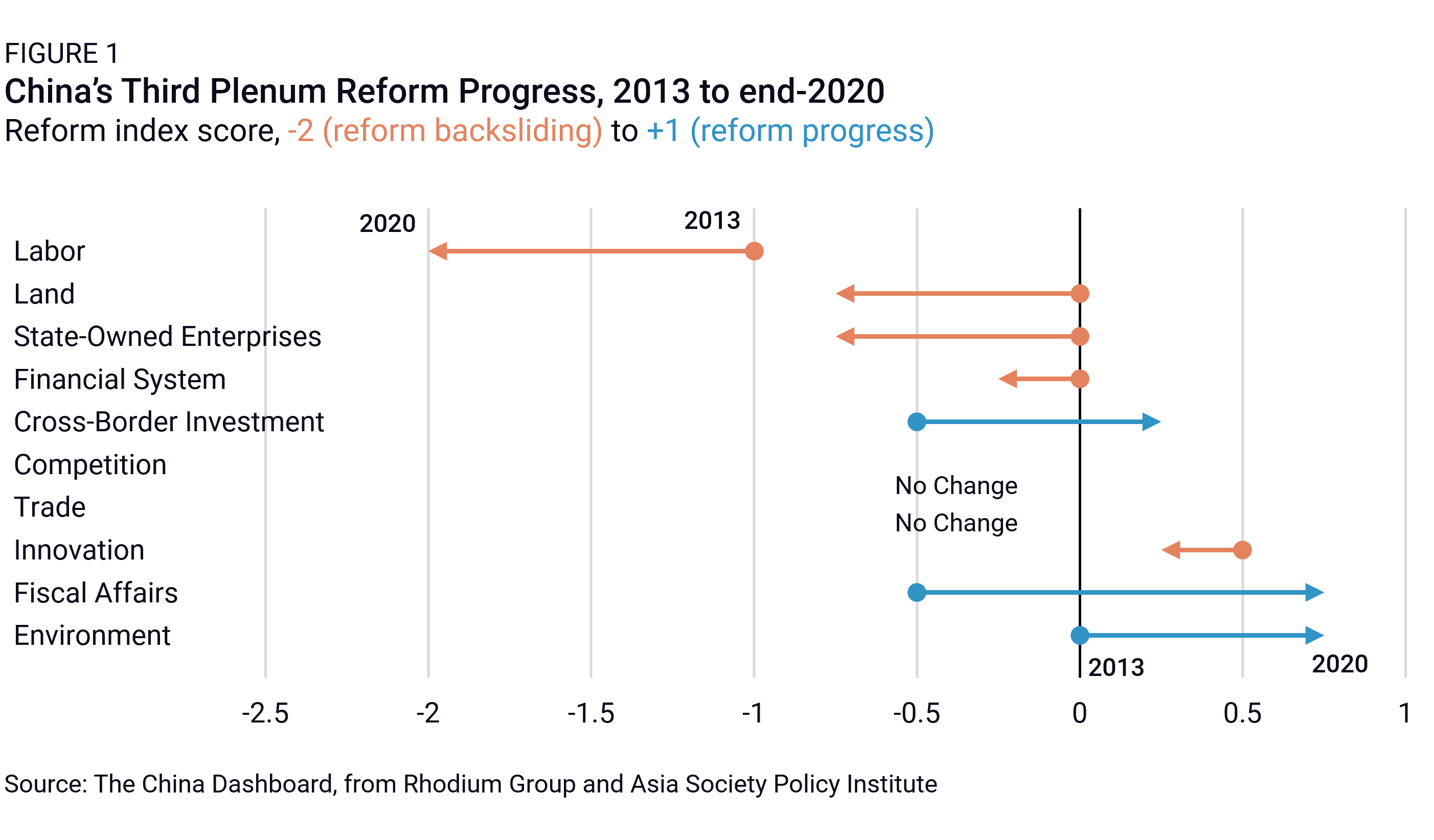

Facing sharper economic and social challenges in 2024, policymakers must also confront the challenge of actually implementing reforms announced at the Third Plenum. The 2013 reform agenda was both ambitious and substantial, and China did accomplish some of the goals stated within the “60 Decisions” document released that year. Rhodium Group’s tracking of reform implementation from 2013 to 2020 in our China Dashboard found modest improvements in environmental conditions and in fiscal affairs, among other categories. Yet in most areas, reforms stalled or were eventually reversed, following policymakers’ alarm about the consequences of market-driven adjustment.

Where reforms would have been most disruptive—and precisely where they were most needed—critical measures were pushed off to avoid incurring economic and political costs. These included efforts to reallocate credit and address moral hazard in China’s financial system; to unlock private enterprises and curb policymakers’ preferences for state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and to improve the social welfare system and rural outcomes. Although this avoided compounding stress on China’s system in the short term—after the stock market crisis of 2015-16, amid the US-China trade war beginning in 2018, and during the devasting COVID-19 pandemic that spread worldwide in 2020—it left key reform tasks unaccomplished and only ensured that they would be more difficult to accomplish in the future.

The continued need for structural reform is clear, and in the simplest terms requires the following, at the very least:

Despite the urgency of structural reform for continued economic growth, there will remain a large gap between what Beijing will actually deliver at this year’s Third Plenum in terms of reform and what is necessary for more sustainable growth and alignment with the rest of the world. When the “60 Decisions” were released at the Third Plenum in 2013, years of past reform in China had banked credibility that Beijing would deliver again. That credibility has been lost over the past decade, whether Beijing recognizes it or not.

The substance of the official declarations at this year’s Third Plenum will likely be evaluated based on how seriously Beijing assesses its credibility deficit and uses the meeting’s decisions to rectify it. The best-case outcome for Beijing of public perceptions after the Plenum would be widespread surprise among both domestic and foreign investors at the clarity and depth of non-reversible reforms that raise the prospect of stronger economic growth and declining external imbalances. The worst-case outcome would be post-meeting commentaries that dismiss Beijing’s pledges as more examples of talk without the realistic prospect of action.

The current policy noises in Beijing do not point to fundamental reform of the economic model, nor do the speeches and articles that have been circulating over the past few months surrounding the content of the Third Plenum. At most, they point to incremental changes on key structural issues or more sector-specific adjustments. The most significant shift explicitly under discussion may be the goal of a unified national market or breaking down local protectionism. Against the list of critical reform objectives above, Beijing appears to be discussing the priorities detailed below.

Beijing has long emphasized the importance of unifying national markets, relative to the threat of local protectionism. Chinese private firms have historically oriented toward export markets in part because of the difficulties of expanding domestically, encountering frequent local barriers to market entry and competition. Internet platform companies are the exception that proves the rule—online commerce could expand quickly nationwide because there were few local competitors in their way. Many of China’s regional integration projects (Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei or Jing-Jin-Ji, the Greater Bay Area, and others) are designed in part to break down provincial barriers to commerce.

There have been several statements in recent years concerning the importance of developing a unified national market. A March 2022 document entitled “Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on Accelerating the Construction of a National Unified Market” detailed many priorities, of which regional economic integration featured significantly.

The issue is likely to be reframed at the Third Plenum with greater salience because of the international concern about China’s overcapacity. As local protectionism drives excessive investment, Beijing could position these reforms as one of the potential long-term solutions to overcapacity and China’s export-led growth. Hukou reform (China’s household registration system) could also fit into this construct, as a unified labor market would be a critical part of breaking down local economic barriers as well.

One sector that specifically needs guidance toward a unified national market is the power sector, given the significant changes that the falling costs of solar energy are now delivering to electricity markets. Historically, most power plants in China would strike long-term contracts with provincial utilities, and these are currently responsible for around 79% of transactions. But the intermittency of wind and solar energy makes it difficult to match supply with demand consistently. Long-distance transmission of electrical power from China’s northwest to more developed coastal provinces in the east is also a challenge.

Expect to see some discussion of the need for a unified energy spot market emerge from the Third Plenum decisions, which would allow more immediate and flexible energy trading. There are currently three provinces with fully functioning spot markets, with the latest in Shandong approved in June. Spot markets can connect buyers and sellers more efficiently, facilitating shorter-term transactions that can better accommodate the fluctuating nature of renewable energy. This shift is crucial for promoting more extensive use of renewables and meeting China’s carbon emissions goals.

Interprovincial energy trade also plays a vital role in this transition. Currently, only 20% of electricity transactions occur across provinces, indicating a significant opportunity for integrating national markets. Expanding interprovincial connections can help balance supply and demand over longer distances, making the grid more resilient and efficient. This requires an extensive expansion of the grid infrastructure to manage the increased load and ensure reliable energy distribution and grid stability.

Beijing could also pledge to further liberalize some sectors to foreign investment or remove joint venture requirements in an effort to work toward a unified national market. Beijing has been heavily focused on publicly rebutting the derisking and decoupling narratives throughout the past year, and the Third Plenum is an opportunity to demonstrate renewed commitment to maintaining an open market for foreign firms and new investment. Announcements of limited liberalization steps following the Third Plenum may be targeted in areas designed to answer criticism of China’s industrial policy, such as in the auto sector.

Fiscal system reform is absolutely essential for rebalancing China’s economy toward domestic consumption. Both the system of revenue collection and the distribution of expenditures must shift away from encouraging investment-led growth and toward household consumption. One important example is China’s value-added tax system. In theory, the VAT is a consumption-based tax, but in practice, its distribution (50:50 between local and central governments) encourages additional output from localities within their jurisdictions, as opposed to consumption of goods, which can occur anywhere in the country. Changing that distribution or more generally remedying the imbalance between central and local revenue collection and spending responsibilities will be a critical priority. Tax revenue has continued slowing by around 6 percentage points of GDP over the past eight years, along with investment-led growth. China needs a tax system that covers a rebalancing consumption-led economy, not legacy heavy industries.

The more pressing fiscal reform is prioritizing transfers of additional income or fiscal resources to households. Household income as a share of GDP remains low by international standards, at 61% according to China’s 2021 flow of funds data (and even lower by other measures). The uneven distribution of that income remains a key constraint on consumption growth, with wealthier households less likely to spend a marginal yuan of income.

A long-term solution to local government debt problems is also needed, since the level of debt is preventing fiscal policy from being used counter-cyclically at present. Furthermore, Beijing will need to unveil a new system for financing quasi-fiscal local government infrastructure investment, given the high cost of borrowing for LGFVs from commercial banks and the bond market. Both the stock and the future flow of local government borrowing urgently require new solutions.

The most likely discussions of fiscal policy at the Third Plenum will be some attempt to consolidate the categories for VAT, to unify taxation of goods and services industries, and to improve revenue sharing between central and local governments. An expansion of consumption-based taxation is likely to be discussed as well, but the devil will be in the details, given the difficulties of balancing the benefits of expanding the tax base with the costs of stifling consumption growth. Besides some discussion about expanding the social safety net, a fundamental shift toward transfers to households or other efforts to boost household incomes does not appear to be under discussion.

China’s leadership has started to frame the push for technological innovation in the context of encouraging “new quality productive forces” that will boost overall productivity growth. China’s “New Three” industries of electric vehicles, solar photovoltaic cells, and batteries are all likely to be mentioned as ongoing priorities.

China’s industrial policies have been a significant global irritant as Beijing will remain committed to manufacturing-led growth rather than pushing for a structural economic shift toward consumption and domestic demand. Fundamentally, the only way for China’s economic growth to exceed growth in the rest of the world while pursuing an export-led development strategy would be to grab additional export market share, risking even more serious trade defenses in response.

While the Third Plenum will likely legitimize China’s industrial policy strategy to encourage greater innovation in certain industries, the impact on total factor productivity growth, and therefore economic growth, remains to be seen. One of the more significant signals will be the prioritization of China’s industrial policy objectives within the context of the documents to emerge from the Third Plenum, relative to other reform priorities.

Land reform is perhaps the least discussed element of China’s reform agenda, but is arguably among the most important. Rural residents in China are entitled to work on a homestead plot of land, but do not own it, and therefore cannot profit from its sale or rental income. Obviously, changing this ownership status would allow rural households to access income from their land, which would increase spending power significantly, and arguably kickstart an additional wave of urbanization. But the time to do so was probably several years ago, when land would have fetched better prices in the market. Local governments still remain highly opposed to altering their own ownership rights without more significant fiscal reforms.

Beijing can also use changes in annual provincial land quotas to prioritize greater economic efficiency, rather than regional equity. Currently, more land quota per capita is allocated to less developed provinces, as a way to boost land sales revenues in those areas. A shift in priority would imply a focus on faster growth and de-emphasizing infrastructure investment in China’s interior, where it is less likely to be efficient.

Since 2015, we have kept a vigilant watch for credible structural reform in two long-term research projects, China Dashboard and China Pathfinder. On the tenth anniversary of the serious 2013 Third Plenum that restarted reform momentum, we contrasted recent policy promises with the ambitious earlier goals that remained unmet. Some examples of signals we proposed watching for as evidence of credibility:

The most significant positive surprise, even relative to these expectations, would be clear messaging that new fiscal transfers would improve household incomes and wealth, either through rural land reform, consumption coupons and other transfers, or other progressive changes in the fiscal system. On the flip side, a clear focus on strengthening Party leadership while avoiding or only cosmetically addressing the key issues we mentioned above would be a major disappointment.

Importantly, these signposts of policy change do not require Beijing to embrace new ideas from abroad, only concede that its own past diagnosis of work to be done was correct and remains undone. But since these promises have been rolled out before and Beijing’s stock of credibility built from more serious reform in the 1980s and 90s is depleted, the most crucial signal would be a concession of recent errors. Even the best announced policies will come to naught if their implementation cannot be evaluated honestly, so the first order of business is to deliver a heavy dose of honesty. How Beijing messages this—and how those messages are received—is the acid test.

Note

China's economic policymaking process appears broken, or at the very least impaired.

Note

China may see a cyclical recovery to perhaps 3.0-3.5% growth in 2024 as the property sector bottoms out, but structural slowdown will remain the dominant story for years to come.

Note

China’s economic growth will slow significantly over the next decade. One of the most important drivers of this slowdown is the unwinding of an unprecedented credit bubble

Note

In October, China's Communist Party will unveil changes in its leadership - except at the very top. Here is what we are watching for at the 20th Party Congress