No Quick Fixes: China’s Long-Term Consumption Growth

We explain what is holding back household consumption in China and examine the policy debate over how to catalyze consumer spending.

Executive summary

Investment-led growth has peaked in China, as the financial system can no longer generate the same pace of credit expansion as in the past decade. With this source of growth drying up, household consumption growth will be the single most important determinant of China’s long-term economic trajectory and growth rate.

In this report, we explain what is holding back household consumption in China, examine the policy debate over how to catalyze consumer spending, and offer a range of long-term forecasts for consumption growth. Key findings include:

- In the absence of significant fiscal reforms, long-term household consumption growth is likely to slow to around 3-4% per year in real terms over the next five to ten years. At most, household consumption will contribute around 1.5 percentage points of GDP growth per year, which is likely to limit overall long-term GDP growth to around 3%, given the known headwinds to faster investment growth.

- China’s household consumption growth has slowed more sharply in recent years than official economic data claims. Household savings have risen significantly and consumer confidence has collapsed. Alternative data series point to declining household spending in 2022 and only a modest recovery in 2023 and early 2024.

- Household consumption is constrained in China by low levels of household income and a highly unequal distribution of income. Fiscal transfers from the state to lower-income households would catalyze additional spending, as would a more progressive distribution of income. Reducing savings rates alone is unlikely to boost overall spending significantly, given the low levels of savings among lower-income households.

- There are no quick policy fixes to China’s slow pace of household consumption growth. The imbalances in China’s economy have widened for several years, and only a complete restructuring of the economy, the fiscal system, and a government-led redistribution of income will change that pattern.

Introduction

China’s economy is slowing once again, and weaker household consumption is the primary cause. Retail sales growth so far in 2024 has reached only 3.7% (equivalent to only around 1 percentage point of GDP growth), while household disposable income growth is only 5.4%. Household borrowing remains under pressure from low levels of consumer confidence and the flagging property market. The imbalances between domestic and external demand have widened, with China producing persistently large trade surpluses, now reaching $858 billion over the past year, or around 4.8% of GDP. The slowdown in household consumption places the Third Plenum meeting this week into even greater focus, as calls for structural reform to rebalance China’s economy are multiplying.

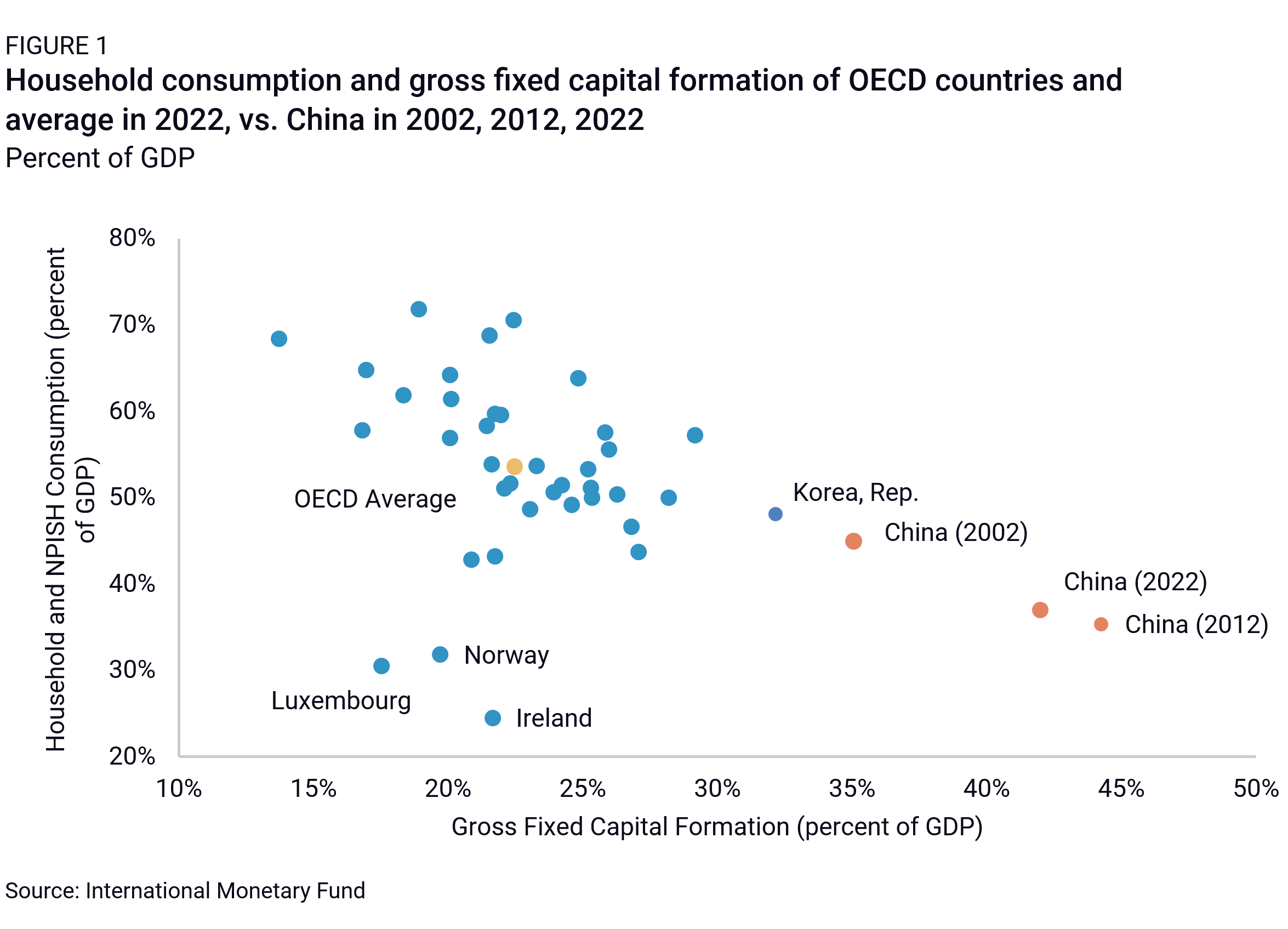

This quarter’s disappointing growth has been driven by decades-old problems. Rebalancing China’s economy away from investment and exports and toward household consumption has been the stated priority of China’s leadership ever since the 2004 Central Economic Work Conference. Yet two decades later, China’s economy remains investment and export-led, while household consumption remains at 39% of GDP, far below averages in OECD economies of 54% (Figure 1). Moreover, consumption as a share of GDP has been declining as China continues developing. Why has China’s leadership failed to achieve its declared primary economic objective over the past two decades? And what would it take to change this pattern now?

Any long-term forecast of China’s economic growth requires either assessing the drivers of potential growth—labor, fixed capital formation, total factor productivity—or an outlook for the expenditure-side components of GDP growth—consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports. Over the next decade, potential growth estimates are probably less useful for most China-focused economic analysts because China’s economy will almost certainly grow at rates below potential. The financial system simply cannot maintain the same credit and investment expansion as in the past decade (See “The End of China’s Magical Credit Machine”).

As a result, an expenditure component-based outlook for China’s growth over the next decade is more useful. Among the expenditure components, the outlook for China’s household consumption holds the most uncertainty. Investment growth will likely remain weak and within a narrow range, given the constraints in China’s financial system in expanding credit. Those constraints are already apparent in the weakness of property construction and localities’ struggles to fund new investments. Fundamental reform of China’s financial system would change the outlook for investment, but appears unlikely at this point. Similarly, government spending is less reliable as a driver of growth given the constraints on China’s fiscal policy (See “The Myth of China’s Fiscal Space”). Exports are never a persistent driver of economic growth, given changes in the global business cycle. China’s economic growth over the next decade therefore depends heavily upon household consumption growth, including domestic spending on goods, services, travel, entertainment, healthcare, and more.

In constructing a forecast for long-term household consumption growth in China’s economy, this report is organized as follows. The first chapter assesses current trends in China’s household consumption, and compares China’s consumption levels and share of GDP to other major economies. It also examines the available data sources covering consumer spending trends and problems with those data sources in 2022 and 2023 in particular. Chapter 2 discusses the current state of policy support for consumer spending, and the limits on using income transfers to support consumption. Chapter 3 highlights the debate over the constraints on China’s consumption growth, and the implications of that debate for policy solutions. Chapter 4 discusses the importance of tax and fiscal policy in maintaining China’s current imbalances between investment and consumption, and the importance of fiscal reform. Chapter 5 introduces longer-term factors that could impact China’s consumption growth over time, including demographic changes, the wealth effect from declining property prices, or rebalancing China’s consumption toward services and away from goods. Chapter 6 highlights some of the reforms and policy choices, such as land and hukou reform, that could cause a break from recent trends, and produce faster consumption growth. Chapter 7 concludes and synthesizes these factors in the context of other economies’ performance after reaching China’s current level of around $12,000 in GDP per capita, and offers a forecast of household consumption and its impact on China’s overall GDP growth over the next decade to 2035.

The state of household consumption in China

China’s household consumption in an international context

China’s aggregate household consumption levels have expanded significantly over the past two decades, consistent with the growth of China’s economy. But consumption’s share of the economy has continued declining, meaning that investment has grown at even faster rates, while savings rates have remained extremely high. In basic terms, this means that China’s households have decided to save more today rather than consuming more or upgrading their standard of living. Those savings have funded investments for the future, which may end up benefiting both Chinese and foreign consumers.

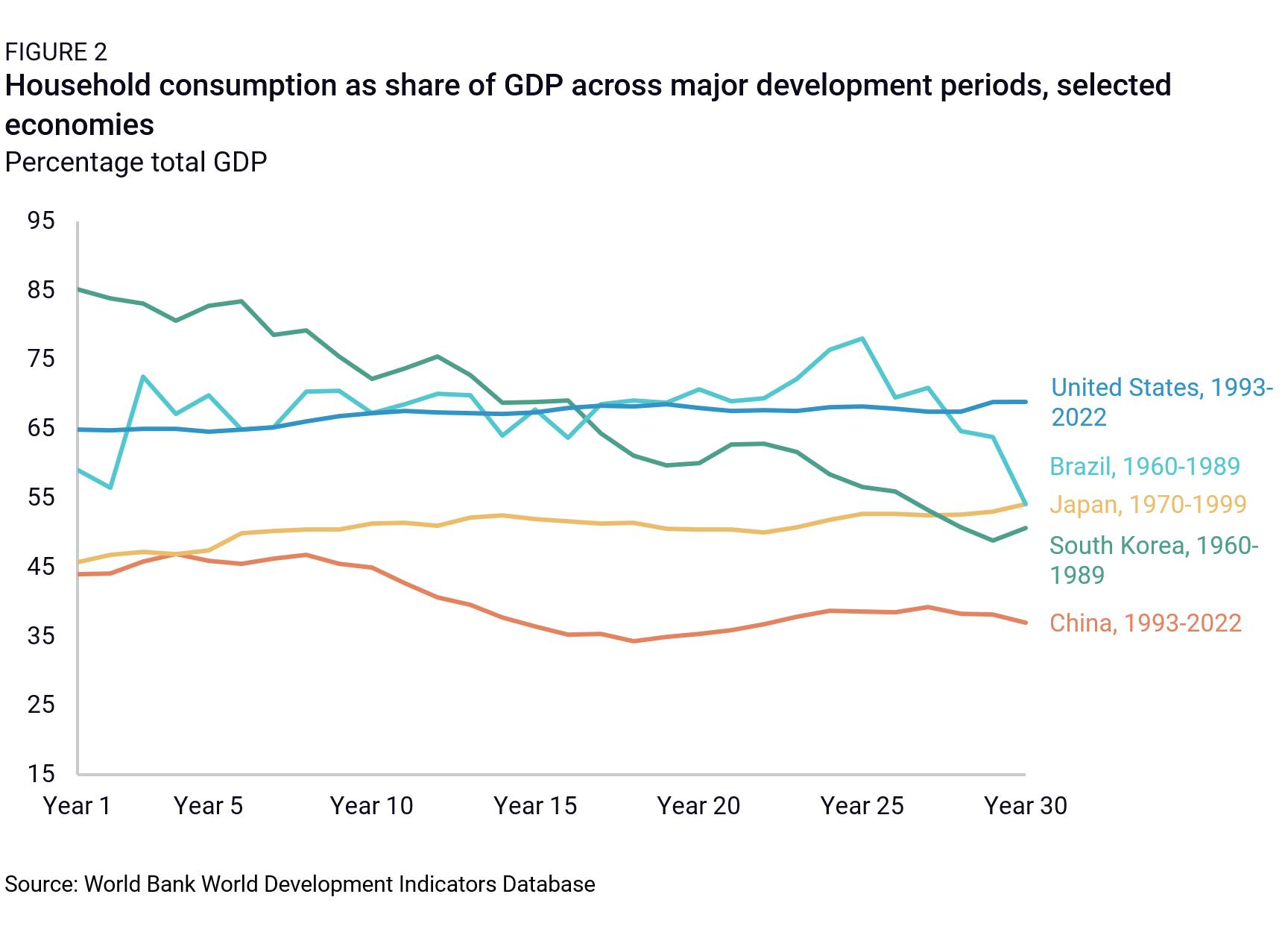

In comparison to other rapidly developing and developed economies, not only is China’s household consumption share consistently lower than its peers, but it has been falling in recent years (Figure 2). South Korea is the only other country surveyed here to experience a major downshift in consumption, but it began at an extraordinarily high level at the beginning of its development period due to weak investment. Furthermore, even though South Korea’s household consumption share of GDP declined rapidly during the country’s investment-led development, it was still over 15 percentage points higher than China’s after three decades. Brazil also experienced a decline, but this was only after robust growth for much of its rapid development phase.

Despite China’s suppressed household consumption expenditure as a share of GDP, consumption in China has demonstrated robust growth in both absolute and per capita terms. Between 1996 and 2022, consumption expenditure per capita grew by 8% annually on average.

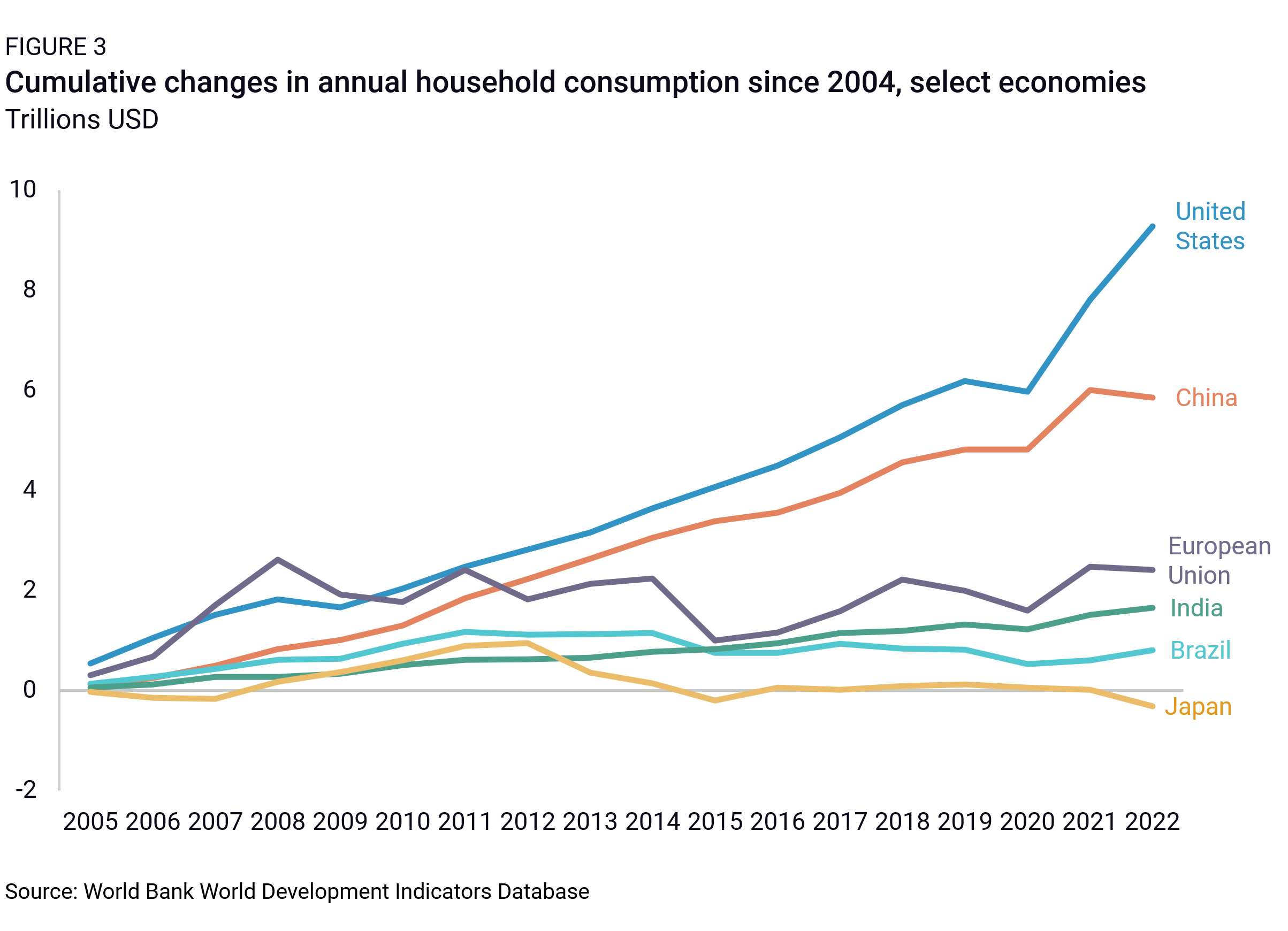

The absolute value of China’s total consumption has also kept pace with comparably sized economies, consistent with its rapid economic growth (Figure 3). Since 2004, China has added twice the cumulative annual consumption of the EU, and 65% of the cumulative growth in annual US consumption. When compared to economies at similar levels of GDP per capita, China’s consumption growth has been far faster over the past two decades.

The obvious corollary is that because China’s investment growth has been even faster over the past two decades, its economic performance is still more dependent on overseas sales than domestic demand. Recently, China’s weaker domestic demand and surging exports have generated trade tensions and concerns about China’s overcapacity (See “Overcapacity at the Gate”).

If China spent the same percentage of GDP on consumption as the European Union or Japan, this would effectively raise annual household consumption in China from $6.7 trillion to around $9.0 trillion, which would likely mean that China would run a global trade deficit and contribute significantly to global demand. But that hope remains very distant, given the realities of China’s unbalanced growth.

Trends in nominal and real consumption growth

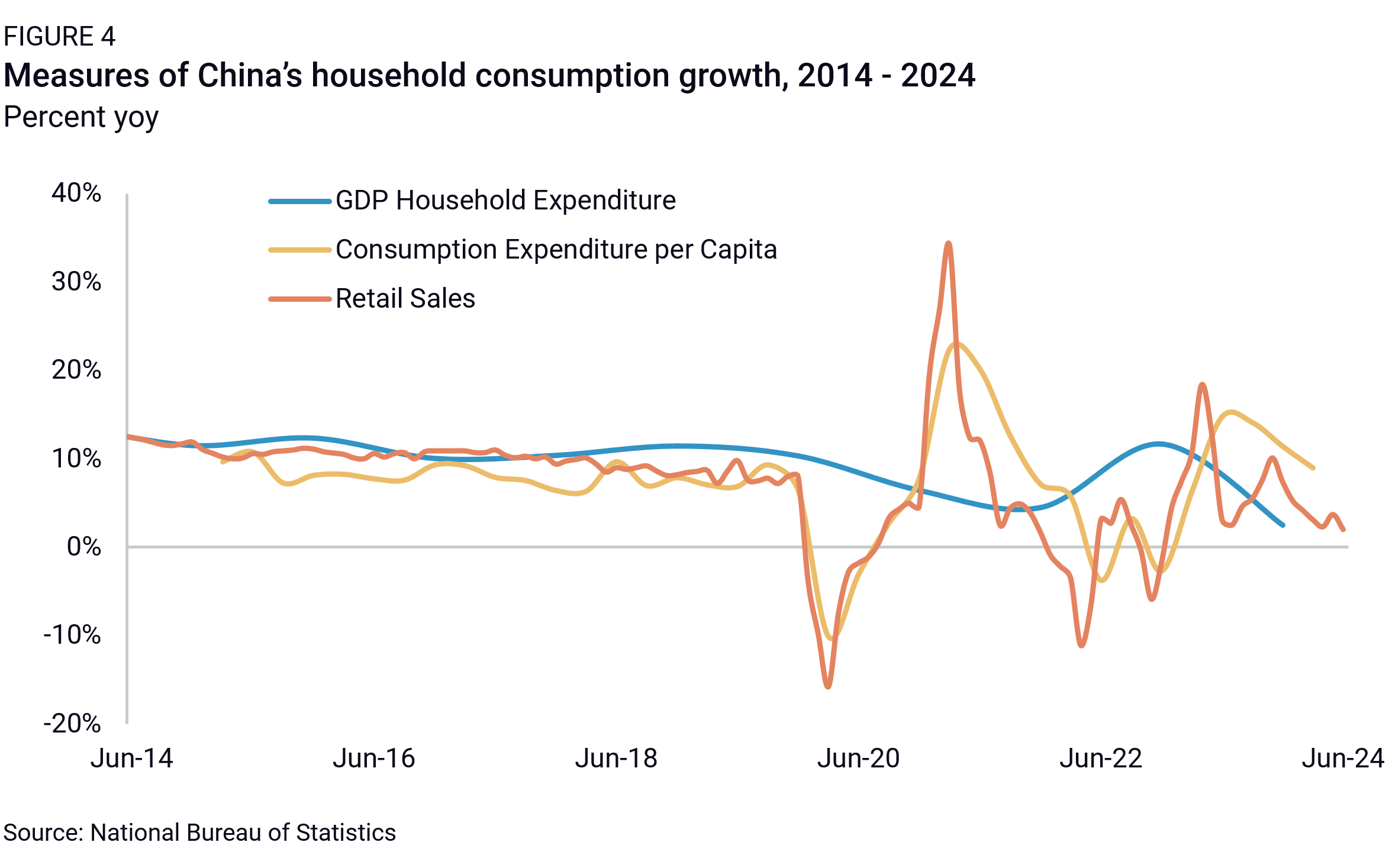

China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) provides several indicators of household consumption growth (Figure 4). Household consumption within China’s GDP is measured annually in expenditure-side GDP data, albeit with a considerable lag. On a monthly basis, retail sales data provide some indication of recent trends in consumer spending, but this also includes deliveries to retailers in some industries, rather than final sales. Quarterly household survey data show trends in per capita spending, but usually with suspiciously little volatility. Household survey data are often inconsistent with consumer confidence survey data from the NBS, financial system data on household savings activity, or other third-party surveys or indicators of consumer activity, such as Alibaba’s online sales levels.

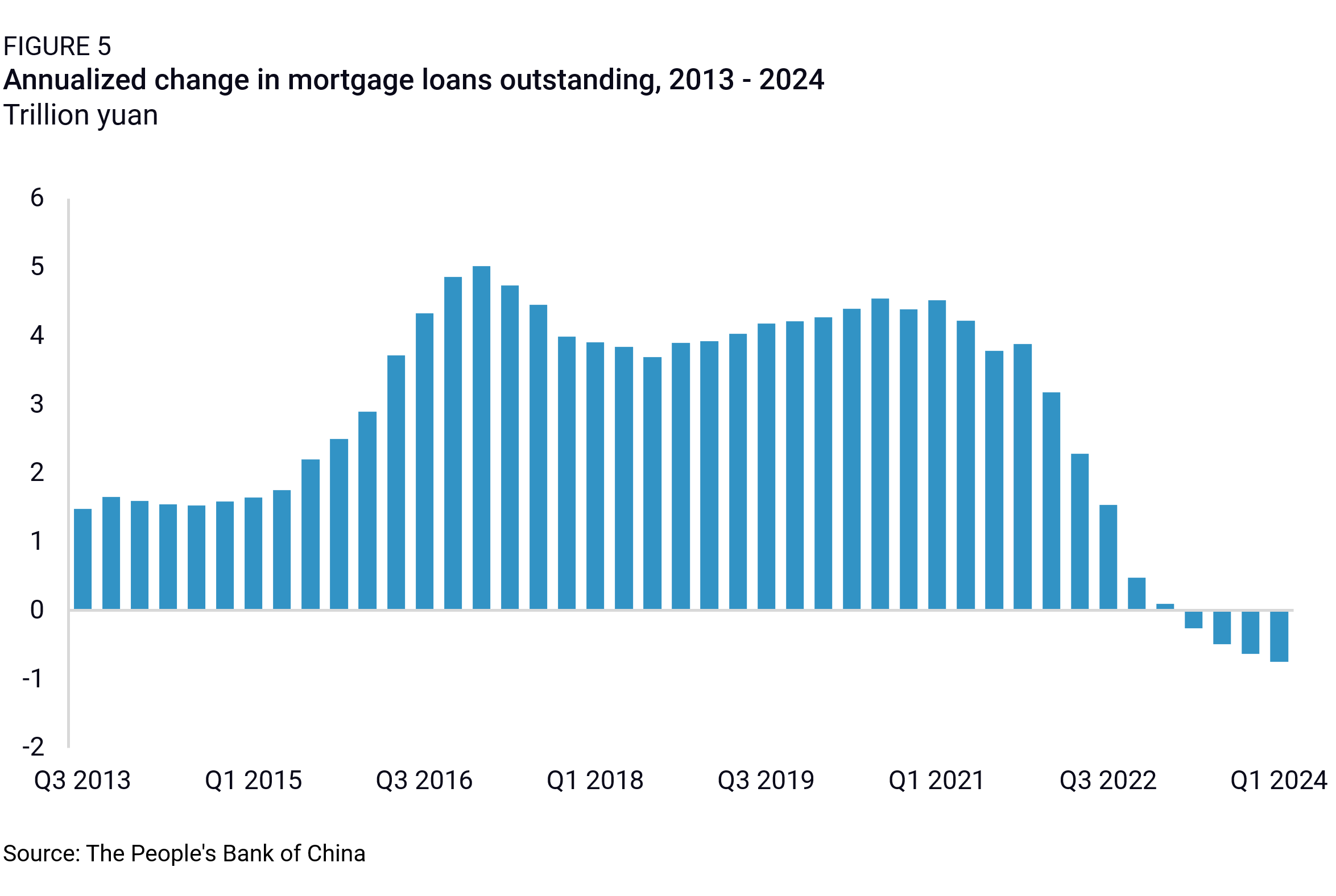

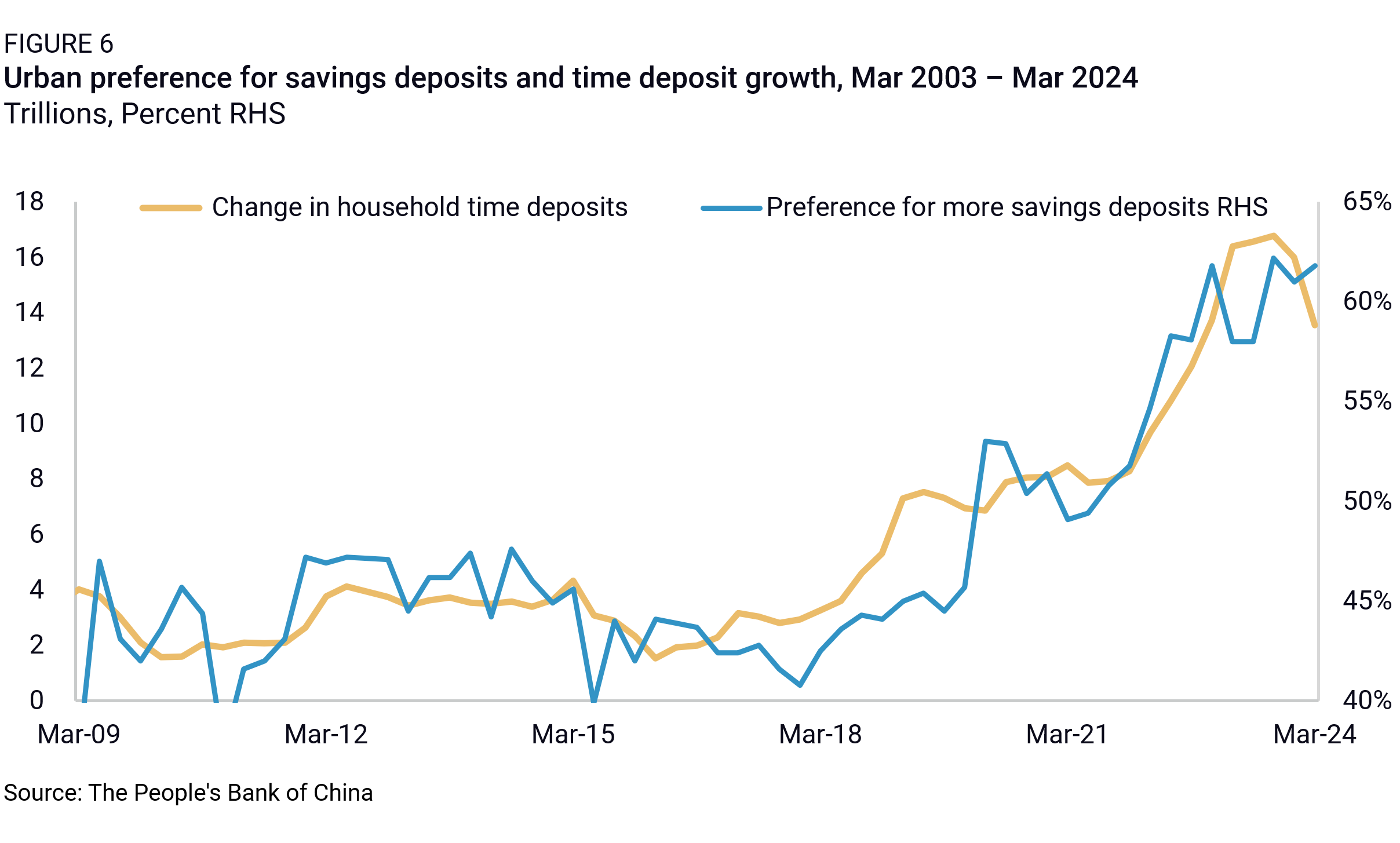

China’s economy slowed during the pandemic years, and COVID-related restrictions in 2022 hit household consumption hard. Even when the restrictions were lifted in 2023, growth rates stayed low. Meanwhile, the collapse in China’s housing market caused consumers to actively pay down mortgages, reducing debt rather than increasing spending (Figure 5). Credit card debt outstanding has also declined since the end of 2021. Household savings have risen sharply in recent years—not only are households saving more, but they are placing those savings in time deposits, indicating little intention to spend in the short term (Figure 6).

These characteristics—rising propensities to save, low consumer confidence, and deleveraging—are not usually consistent with surging consumption growth. Yet official GDP data show no significant slowdown in household consumption in 2023. Taking one step outside the official household survey data and expenditure-side GDP data, however, there is ample evidence of weaker consumer spending.

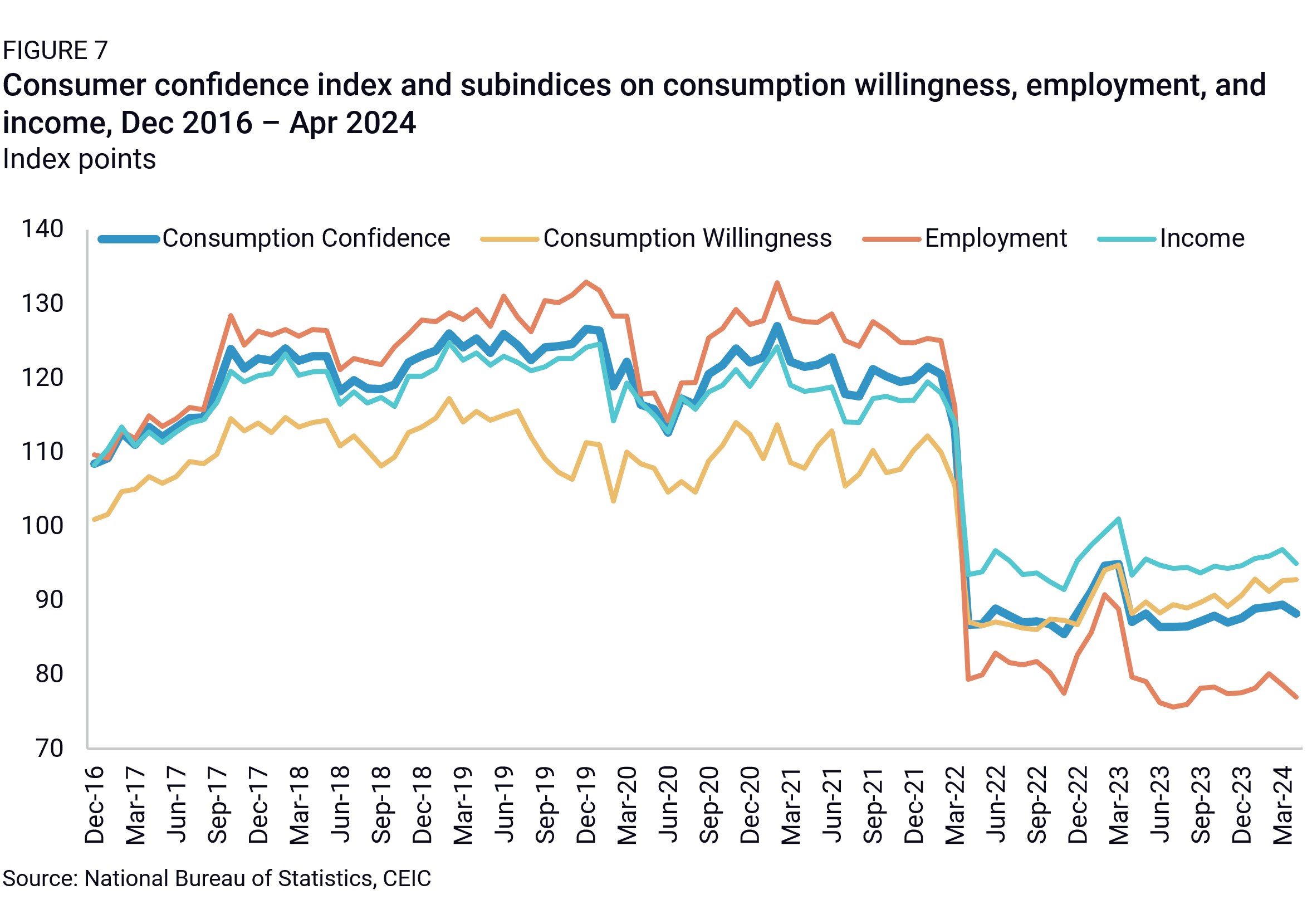

Other indicators of household consumption

While the pandemic dampened China’s consumption in early 2020, the real collapse of the official NBS Consumer Confidence Index followed the Shanghai lockdown in 2022, including controls on mobility throughout the country (Figure 7). Even after restrictions were lifted, consumer confidence has barely improved, primarily due to concerns about employment. The PBOC’s survey of urban depositors showed that the average propensity to consume in 2023 has declined by 4 percentage points from 2019 levels, while the propensity to save and deposit increased by 15 percentage points.

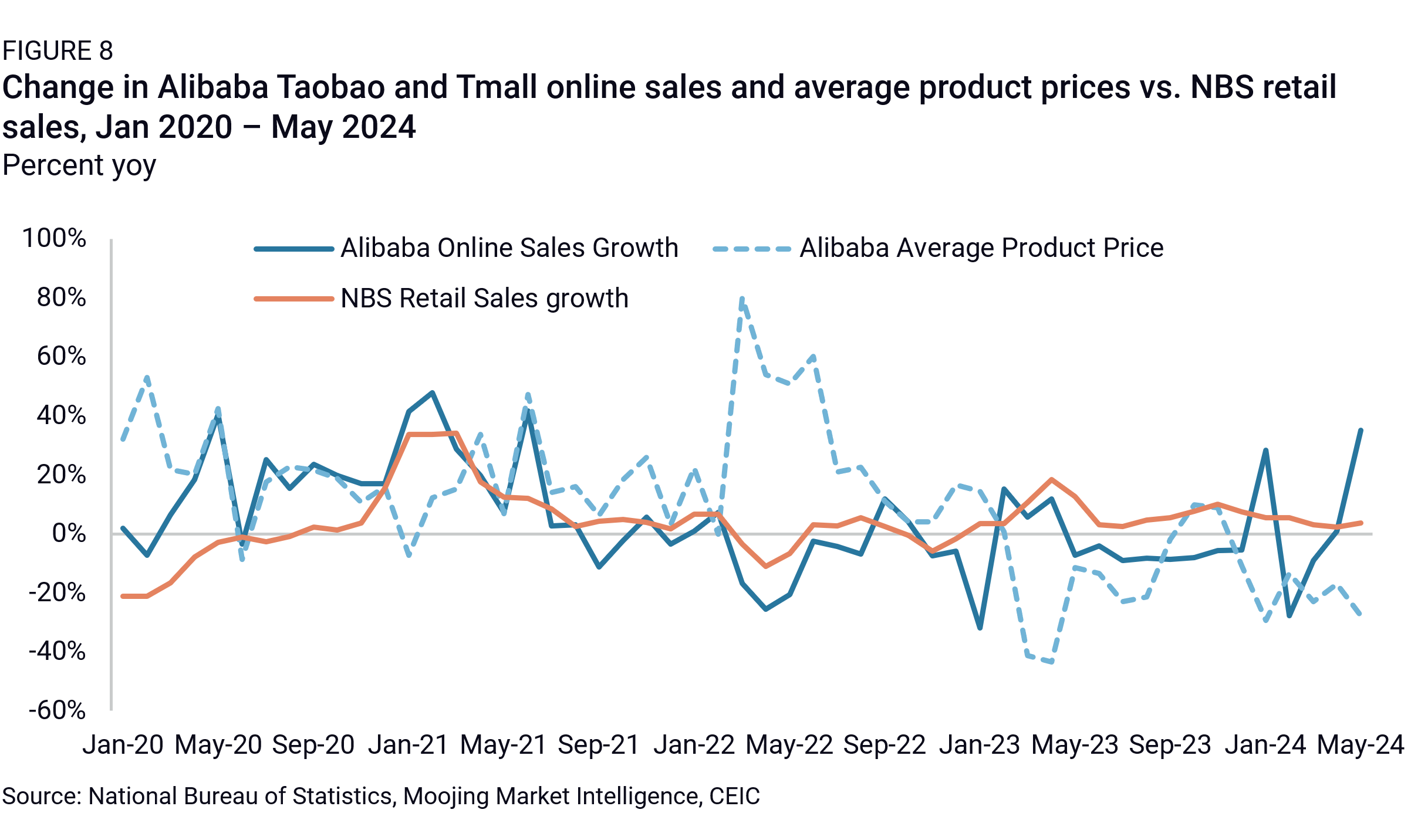

Income inequality expanded during the pandemic, leading to a “K-shaped” recovery in consumption and widespread consumption downgrades among the middle class in China. Luxury spending by Chinese people globally increased by 9% in 2023 according to the Yaok Institute, higher than the 7.2% growth of overall retail sales. In the meantime, CPI growth has been hovering around zero for more than a year.

E-commerce platforms have been competing on discounts and low prices, with the average product price of Alibaba online sales sliding by 12% in 2023 (Figure 8). China Household Finance Survey data showed that around a third of households did not have adequate income to cover expenses in 2019, and the situation for these households has likely deteriorated over the past four years.

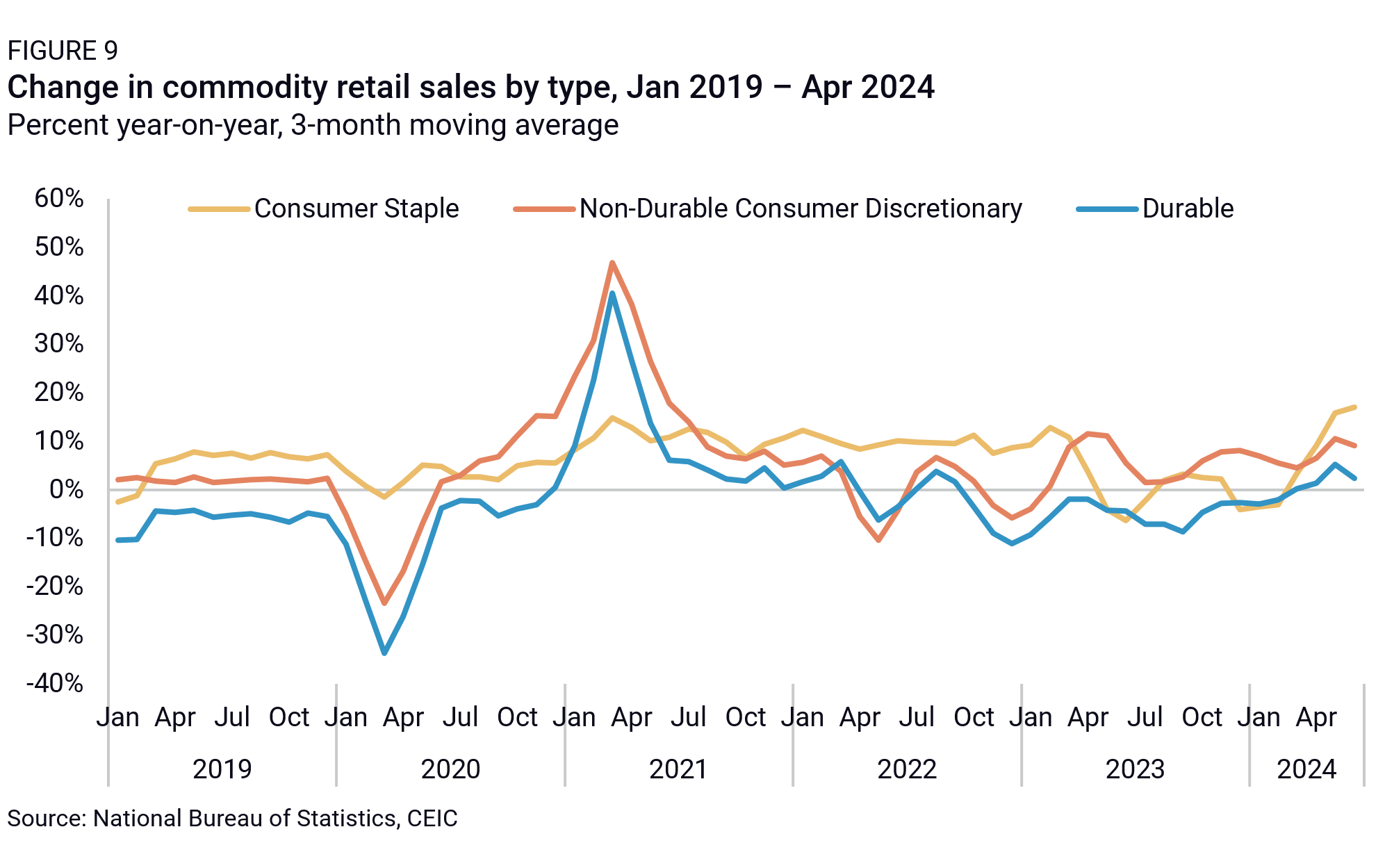

Households spent more on food and other consumer staples during the pandemic (Figure 9) as a precautionary move to handle frequent lockdowns. The proportion spent on food rebounded to 31% in 2022 from 28% in 2019, reversing a downtrend since 1990. After China reopened in 2023, sales growth in consumer staples declined as sales of non-durable discretionary goods bounced back. But the recovery in durable goods was slower, as the property sector’s weakness dragged down spending on furniture and appliances.

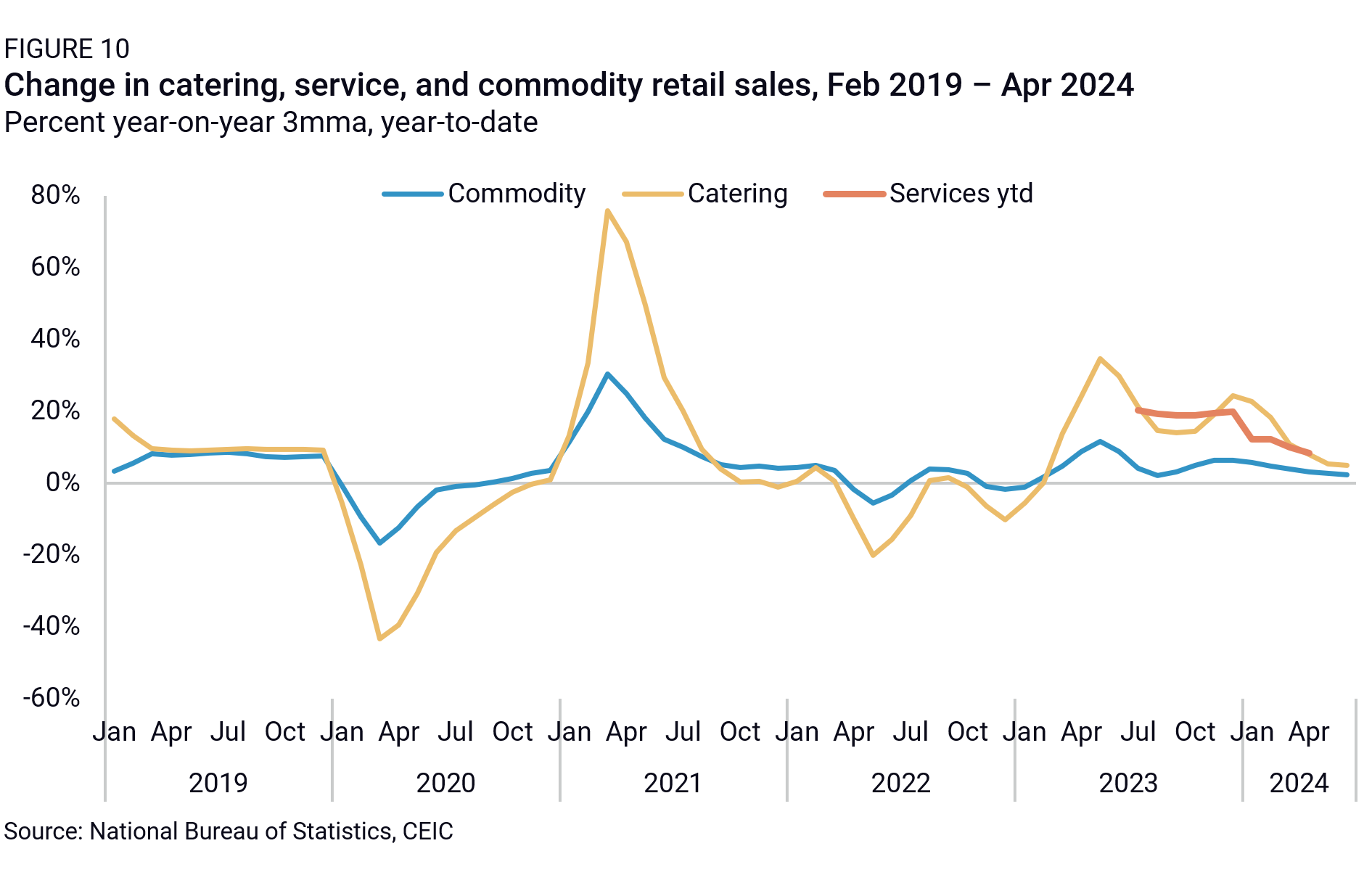

Service sector consumption has been the one bright spot in China’s post-pandemic recovery, soaring by 20% in 2023 while commodity retail sales reported 6% growth (Figure 10). Household expenditures on services accounted for 45% of total expenditures last year, based on a rough breakdown of the categories of the household survey data, and still below developed country levels by 15-20 percentage points, implying further room for growth. The number of travelers has surged during holidays, but tourism spending per capita has remained around 80%-90% of 2019 levels, and services consumption growth is slowing so far in 2024.

A McKinsey survey reported that the most pessimistic group of consumers was middle-class migrants in tier-1 and tier-2 cities. The loss of high-income jobs after Beijing’s campaigns against the property sector, online platforms, education technology, video games, medical, and financial sectors hit these households disproportionately. The squeeze from high mortgage payments and falling property prices has clearly impacted their consumer confidence as well. The survey also found that wealthy elderly residents in tier-1 and tier-3 cities and elderly rural residents were at the two extremes of optimism and pessimism in terms of household consumption. The overall effect of the aging population is likely negative in the short term, given wealthier elderly people are likely in the minority, even if savings rates are likely to fall in the longer term.

Problems in recent official consumption data (2022-2023)

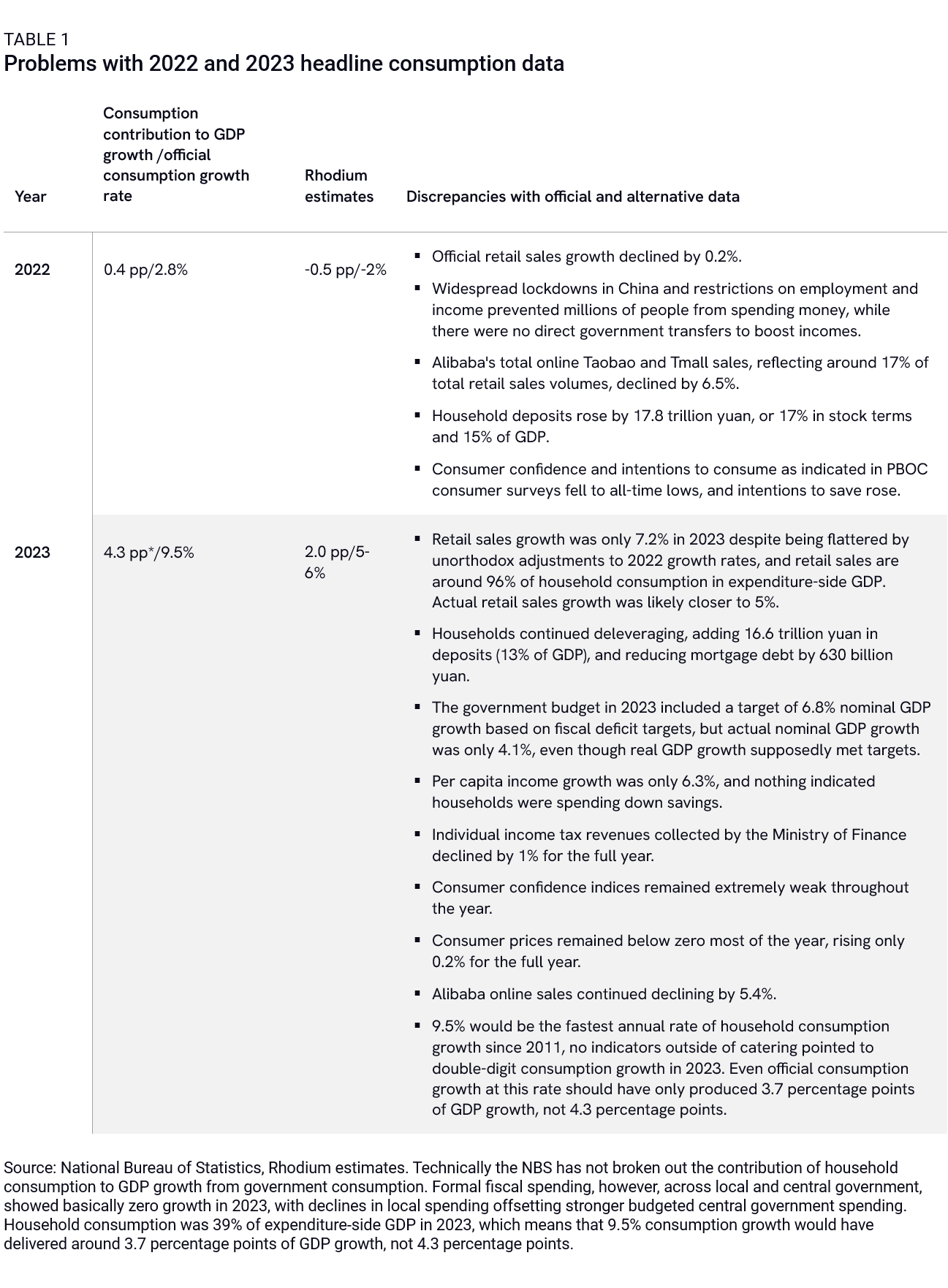

China’s recent headline economic data have been highly problematic, with official GDP growth published by the NBS at 3.0% in 2022 and 5.2% in 2023. The primary culprit is overstated investment activity that obscures the property sector’s collapse, but household consumption growth rates have been problematic as well, particularly in 2023. Household consumption growth was likely negative in 2022 and around 5-6% in 2023, rather than the official nominal rate of 9.5% from China’s expenditure-side GDP series. This means that in 2023, household consumption growth was responsible for only around 2 percentage points of GDP growth, while other components of growth were likely flat or negative. Table 1 highlights the key discrepancies.

There is much more evidence for a structural downshift in China’s consumption growth since the pandemic and the collapse of the property market in 2022 than a return to previous rates of growth. This is consistent with multiple accounts of “consumption downgrades” in China since the pandemic lockdown measures were imposed and with extremely weak consumer price growth. China’s core CPI growth (excluding food and energy prices) has stayed below 1% since 2022, and has downshifted ever since the slowdown in consumer credit under the deleveraging campaign began in late 2018.

In particular, over the past two years specifically, there is little reason to believe that consumption growth has outpaced household income growth (income growth has averaged 5.7% in 2022 and 2023). Household deposits continue climbing sharply and households are still deleveraging and reducing mortgage debt associated with the decline in the property market. With household consumption remaining around 39% of GDP, future consumption growth remaining in line with the reported 5.7% income growth in 2022 and 2023 would suggest only around 2.2 percentage points of annual GDP growth from household consumption in the future, in the absence of aggressive fiscal reforms (to be discussed below). But there are several reasons to assume that household consumption growth and income growth will trend even lower than these rates over time.

Long-term per capita income and consumption trends

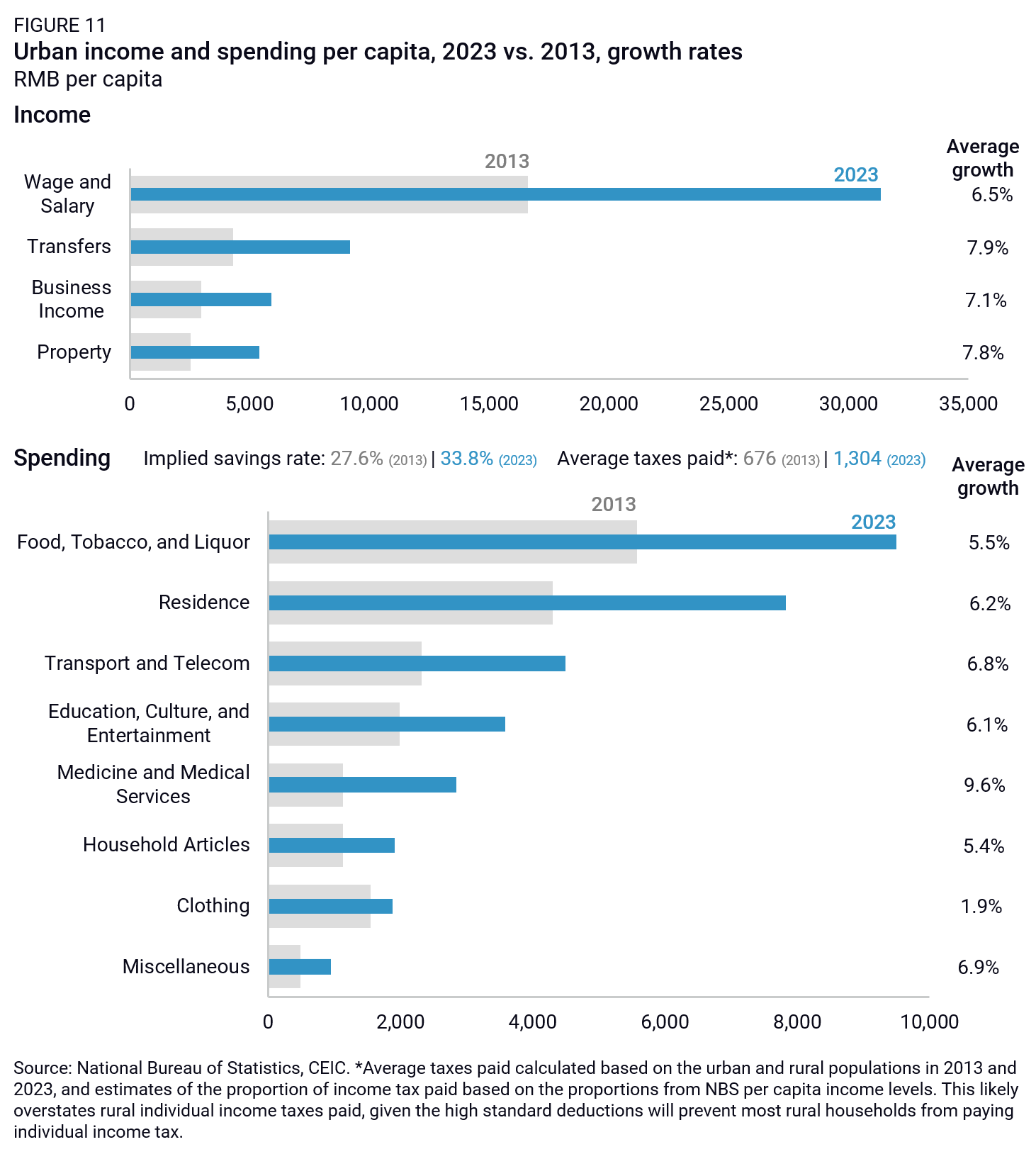

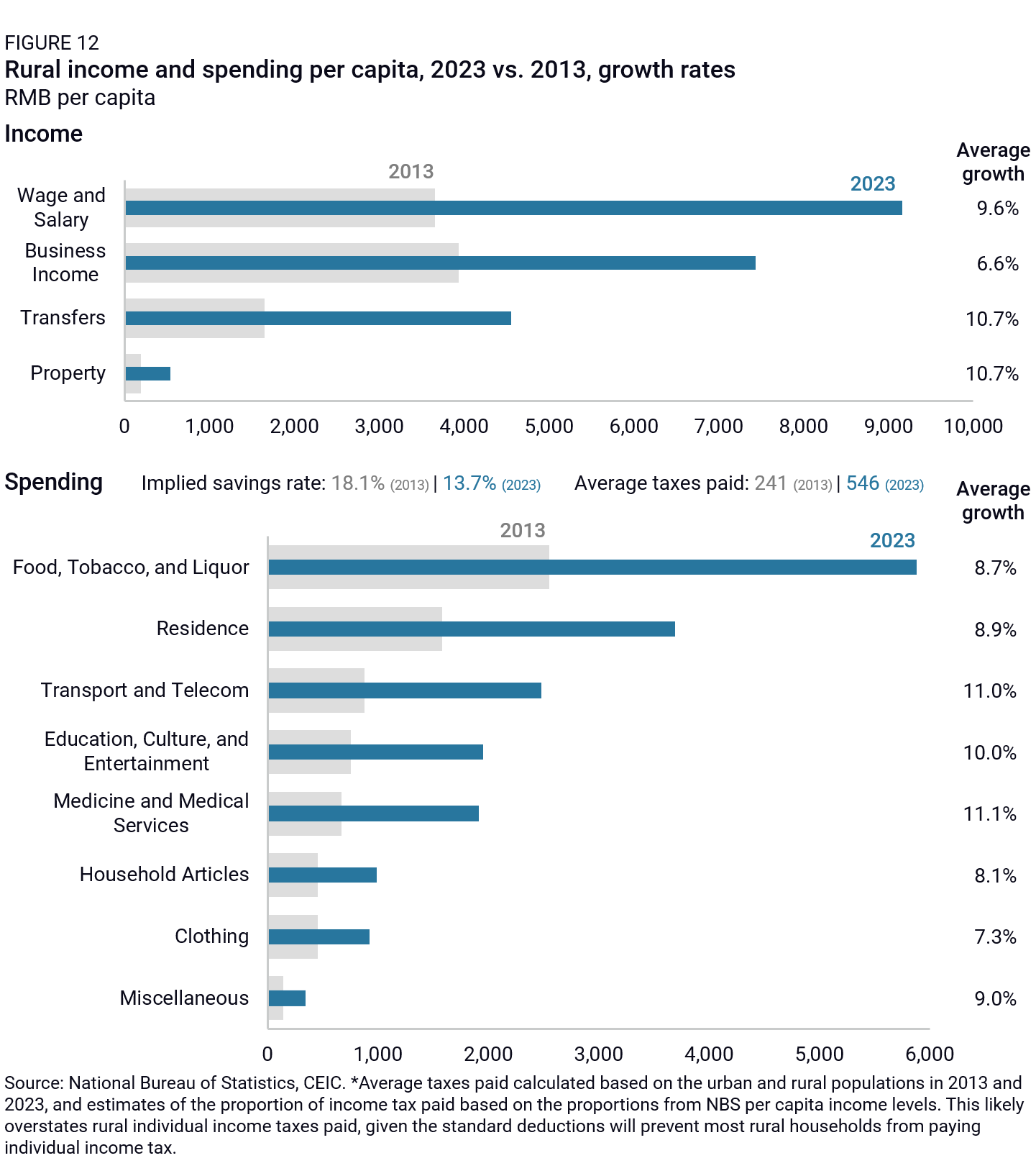

China’s statistics bureau publishes a quarterly survey of trends in per capita income and expenditures, sorted by urban and rural residents. China’s overall population is now declining, so even assuming that these data are accurate, overall consumption growth will be slightly weaker than these rates in the future. Figures 11 and 12 offer a rough breakdown of income and expenditure for the average urban and rural resident, as well as the compound growth rates of income and spending by category over the past ten years, from 2013 to 2023.

A few observations emerge from these charts and from the growth rates over the past decade. First, and most obviously, these rates of consumption growth (6.0% for urban residents, 9.3% for rural residents) occurred during a period of rapid economic growth in China that is unlikely to be repeated in the future. Without dramatic policy changes that would produce a surge in household income, most likely via fiscal transfers, it is unrealistic to assume that consumption growth rates will accelerate from the pace seen over the past decade—and based on the 2024 data, they are already slowing.

Second, implied urban household savings rates have risen over the past ten years, even though urban per capita household income growth has averaged “only” 6.9%. Implied rural household savings rates have fallen slightly. This likely suggests growing wealth inequality in urban areas over the past decade, with most of the rise in household income occurring among wealthier households who are less likely to spend a marginal yuan of additional income. Unless the distribution of income improves, even faster income growth among urban residents may not produce a corresponding acceleration of consumer spending.

Third, the growth rates of spending by category suggest a weakening social safety net, rather than a strengthening one. The fastest growing category of spending for both urban and rural residents is medicine and medical services, where China has made considerable investments over the past decade. Spending on housing-related goods and services has remained roughly in line with overall growth rates of spending, rather than falling.

Fourth, the capacity to unlock consumption growth from rural residents appears limited, without far more significant transfers. China has roughly 477 million rural residents. Even if rural implied savings rates were cut in half from current levels, the implied additional annual spending would only be around 838.6 billion yuan, or around 0.6% of GDP (for urban residents, the equivalent calculation would be close to 7% of GDP). Something more must be done to unlock new sources of income for China’s rural residents, namely more aggressive market-oriented rural land reform.

State of policy support for consumption

As China’s household consumption growth slows, the key question that immediately arises is why Beijing has responded to this weakness in consumer spending so cautiously. Unlike most developed economies, China did not launch large-scale cash transfers to households or tax cuts to boost consumption during the pandemic. Two primary reasons explain this inaction: A distorted and imbalanced tax system produced by China’s investment-led growth model, and Party leadership’s political distaste for incentivizing growth at the consumer level.

A tax system warped by investment-led growth

It is difficult for Beijing to impact consumer behavior through taxes because the existing tax system targets producers instead of consumers. Therefore, cutting or adjusting tax rates produces a minimal impact on consumption. China only imposes consumption taxes on fifteen types of products, mainly consisting of alcohol, tobacco, vehicles, oil, and luxury goods. Beijing is encouraging local governments to use trade-in programs to enhance retail sales, since it is easier to collect subsidies back through consumption taxes. This has been particularly prevalent in the auto sector.

It also remains unclear whether the tax system can meaningfully boost consumption. The 2021-2023 income tax relief program was estimated to generate tax reductions of 110 billion yuan every year. However, according to former finance minister Lou Jiwei, only 14% of the population earn more than 5,000 yuan per month and pay income tax at all. Most Chinese residents—especially the ones who would be likeliest to spend rather than save a windfall—see no immediate benefit from these cuts.

Unemployment insurance also generally fails to cover the most vulnerable group of workers. The insurance program requires workers to pay premiums for one year and provide proof from their former employers to show that unemployment was not voluntary. However, it is difficult for 297 million migrant workers and 200 million “flexible” workers (part-time workers, freelance workers, and individual business owners) to meet these requirements and qualify for benefits.

The primary government program to boost household consumption was very small-scale, with online vouchers totaling tens of billions of yuan per year from 2020 to 2023, less than 1% of annual retail sales. However, the 2019 China Household Finance Survey data showed that only 25% and 35% of the families in the lowest and second-lowest income quintiles had access to online payment systems. The regional imbalance of fiscal resources further limits the benefits available to low-income households in less developed provinces.

A fear of “welfarism”

Beyond fiscal constraints, Beijing’s apparent contempt for consumption and a more robust social welfare and transfer system is a fear of welfare dependency. This perspective is associated with Xi Jinping specifically but extends well beyond Xi within the Chinese government, at the central and local administrative levels.

In Xi Jinping’s own words: “To promote common prosperity, we cannot engage in ‘welfarism.’ In the past, high welfare in some populist Latin American countries fostered a group of ‘lazy people’ who got something for nothing. As a result, their national finances were overwhelmed, and these countries fell into the ‘middle-income trap’ for a long time. Once welfare benefits go up, they cannot come down. It is unsustainable to engage in ‘welfarism’ that exceeds our capabilities. It will inevitably bring about serious economic and political problems.”

As a result, even the government’s large poverty alleviation campaign in the past decade has focused on infrastructure spending and support to local companies, rather than direct financial transfers and social insurance provision to poor households. In the last decade, Beijing also promoted pension payments to elderly people to a greater extent than benefits to working-age households, with the implied logic that people should work hard to enjoy a happy retirement.

With the government’s priorities shifting from investment to high-tech manufacturing, Beijing may turn even harder against the idea of people “lying flat” out of fears of “welfarism.” This ideological constraint may limit any assistance Beijing provides to China’s consumers in the future.

Constraints on household consumption growth

Identifying the drivers of China’s weak consumption growth is a key concern for policymakers in Beijing—different causes require different remedies. The primary explanations generally fall into four categories: low household income levels, income inequality, precautionary savings, and high levels of household debt. If low household income levels are the key constraint on consumption, policymakers should boost disposable incomes. If precautionary savings are the key constraint, the government should instead strengthen social safety nets to reduce the need for such savings. If household debt is the key problem, interest rates should be reduced and debt should be restructured or refinanced.

The bulk of the evidence suggests that a low share of household income and an unequal distribution of that income are the key constraints on household consumption. China’s household income as a share of GDP is lower than most consumption-led economies, but not by significant margins. What is significantly different is the combination of lower household incomes and the uneven distribution of those incomes, with survey work indicating that around 60-65% of China’s total savings may still be held by the top 10% of households. This leaves significant proportions of China’s households vulnerable to consumption downgrades during periods of slower economic growth, such as what is occurring now. Precautionary savings and household debt levels are certainly key constraints as well, but they are not particularly unique to China, and household debt levels are now stabilizing or actually falling, which is also limiting consumption.

Household income as the primary constraint

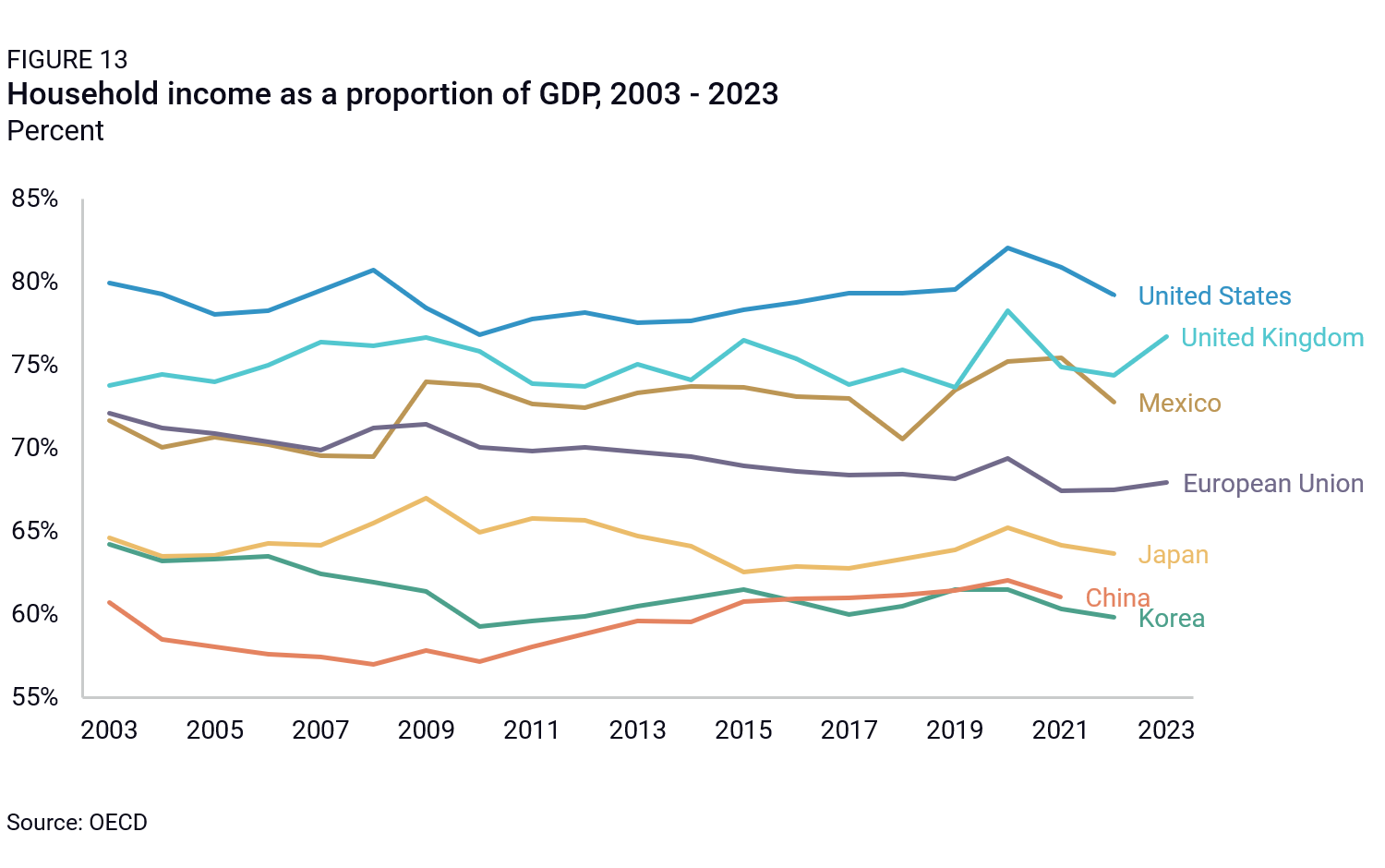

One of the most straightforward explanations for slow household consumption growth is that households simply can’t spend money they don’t have. Household income growth has been sluggish and remains weak as a proportion of China’s economy. This is the consequence of years of rapid investment and export-oriented growth—suppressing interest rates and wages to support investment and labor-intensive manufacturing competitiveness have come at the expense of income for household savers and workers.1 The net result is household income—even including social transfers—that totals only 61% of GDP, below developed country averages (Figure 13).

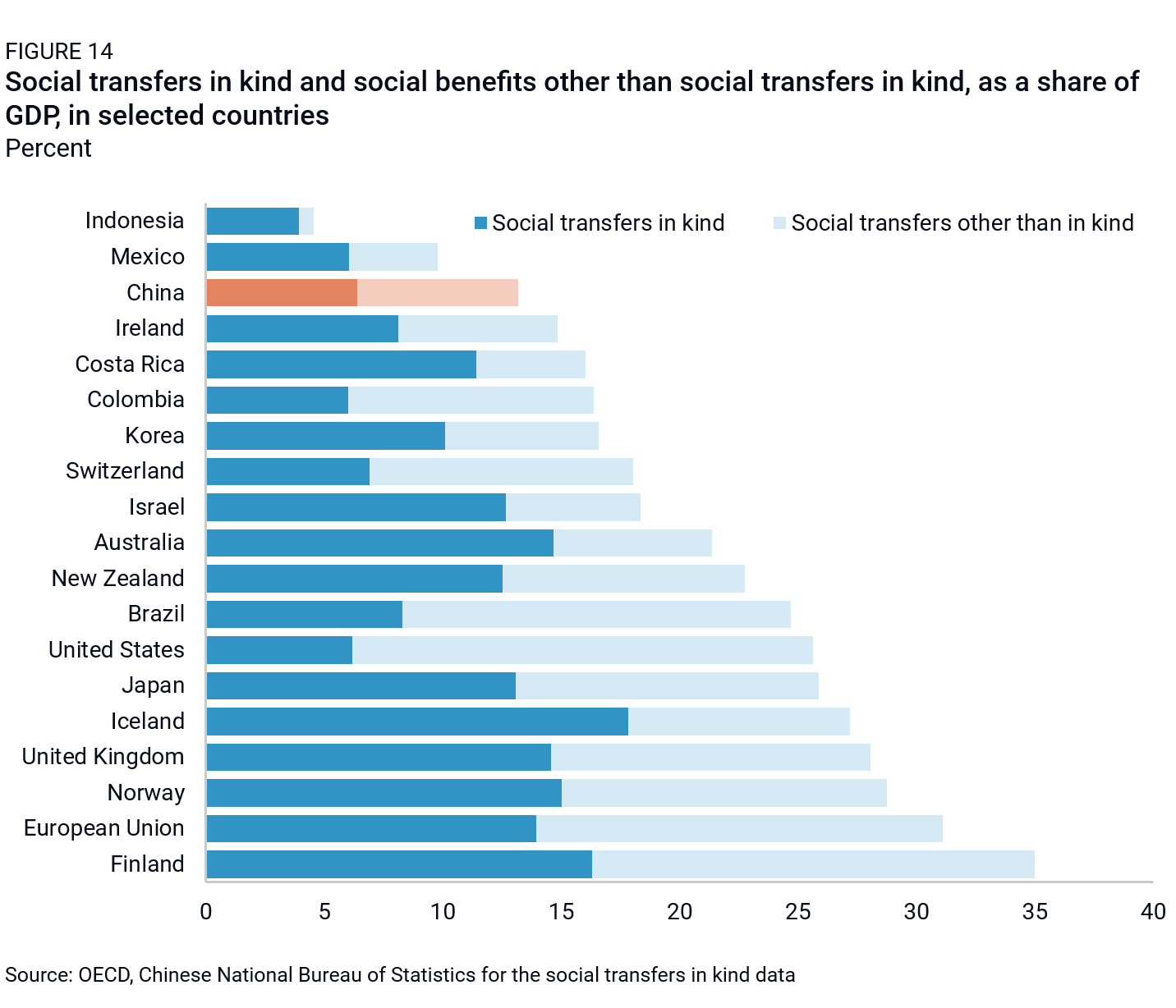

Social transfers can also boost household income relative to GDP, either in kind or through financial transfers. In China, social transfers in cash (through social security, welfare and allowances) amounted to 7.9 trillion yuan in 2021 (or around 6.9% of GDP), while social transfers in kind (i.e., the provision of certain goods or services such as health care and education to households) amounted to 7.3 trillion yuan (or around 6.4% of GDP). But, according to data from the OECD and China’s National Bureau of Statistics, China’s transfers are low compared to OECD countries (Figure 14) and, in general, are roughly equal to required contributions, limiting their ability to boost consumption.

At the end of the day, social transfers are simply government consumption, and do not change the relatively low proportion of combined household and government consumption relative to the size of China’s economy. However, they have important effects on other potential causes of low consumption growth, including income inequality and precautionary savings.

Income inequality limits consumption growth

Another explanation for weak consumption growth is the unequal distribution of household income in China. While wealthier households spend a smaller proportion of their income, poorer households often have to plow all their income into spending on living expenses. Average household income levels are therefore less important than the distribution of income, as lower-income households are unable to spend in line with average income levels, while consumption among higher-income households remains low.

Survey work conducted by Gan Li’s team in the China Household Finance Survey is consistent with this explanation. The survey results show that lower-income households are not able to save at high levels, as savings are overwhelmingly concentrated among the wealthiest individuals. Therefore, even if China could improve the social safety net to encourage rural residents to spend, it would improve social welfare but would not have much of an impact on the overall savings rate or aggregate spending. Gan’s survey work from 2012 showed that at that time, households in the top 10% of household incomes held 69% of total savings and 57% of total income. The situation has not changed considerably since 2012, as official NBS data on the distribution of income also reveals no significant changes in that distribution across income quintiles over the past decade. Data from the China Household Finance Survey in 2019 showed that a third of Chinese households had negative savings rates, meaning they spent more than their incomes, and relied upon borrowing or past savings. Data from China Merchants Bank—one of the largest domestic wealth management-focused banks in China—generally confirms Gan’s findings as well. Their retail banking customer base shows that around 2.3% of the accounts hold roughly 81% of total private banking assets, a highly unequal distribution.

Another issue is the inequality of basic service provision, particularly for medical services. Out-of-pocket medical service costs are much higher in rural areas, so disposable incomes end up being lower for rural households even relative to official levels.

Scott Rozelle’s work on changes in wage growth over time in rural China also suggest income inequality will remain a key constraint on consumption growth. Rozelle and his co-authors have conducted surveys showing that wage dynamics in China are subject to bifurcated markets for labor, with shortages of high-skilled labor producing stronger wage growth but surpluses of relatively unskilled labor producing declining relative wage growth in the services industries.2

What this means is that simply raising the household share of national income may not be enough to raise consumption sustainably. Instead, the rise in income needs to be distributed in a way where it will be spent. After all, marginal propensities to consume will be strongest among the poorest households—if you give a wealthy household 100 yuan, it won’t make much difference in overall spending, but if you give a poor household 100 yuan, they will spend it. The implication of this argument is that income redistribution, most likely through taxes and fiscal transfers, would be necessary to encourage stronger consumption growth.

Household debt as a constraint

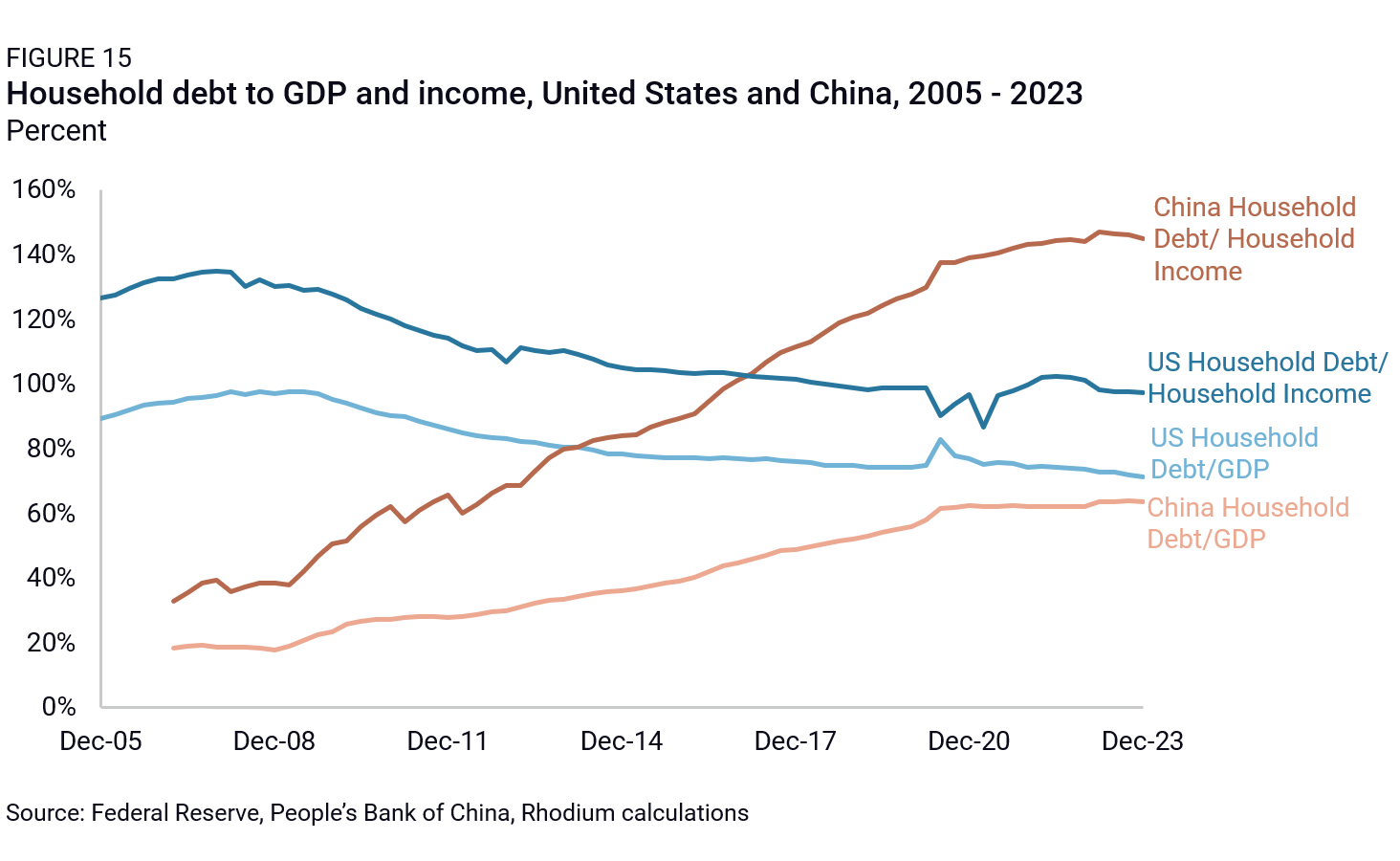

Over the past decade, China’s household debt levels have risen sharply, along with the property bubble and the rise in mortgage finance. As a result, many households are struggling to pay down debts, with little left over to spend on consumption. Household debt has risen by around 32% of GDP from 2012 to 2022, and has since stabilized at around 64% of GDP. Household debt in China is quite large relative to household income, at an estimated 145% according to the household survey data (though somewhat lower according to the flow of funds data). Households started paying down mortgage debt in 2022, which has been one factor contributing to weaker consumption growth and higher household savings over the past two years.

The key implication of this argument is that Beijing should take aim at refinancing mortgage debt and reducing interest rates to boost consumption, particularly among lower-income and indebted households. There is considerable evidence that the combination of income inequality and rising debt levels have limited consumption. Beijing is already taking action, and average mortgage rates have fallen by 194 bps since 2021. This is helpful to households as most of these mortgage rates and the corresponding payments reset every year, freeing up additional income for households.

Precautionary savings and weak social safety nets

Finally, there is the more conventional view that precautionary savings are the primary reason for low household consumption. Social services and medical facilities have been underinvested, and Chinese families have responded by saving a larger proportion of their incomes for emergencies and retirement. If the government were to invest more in social services, households would feel safer and be more likely to spend more liberally.

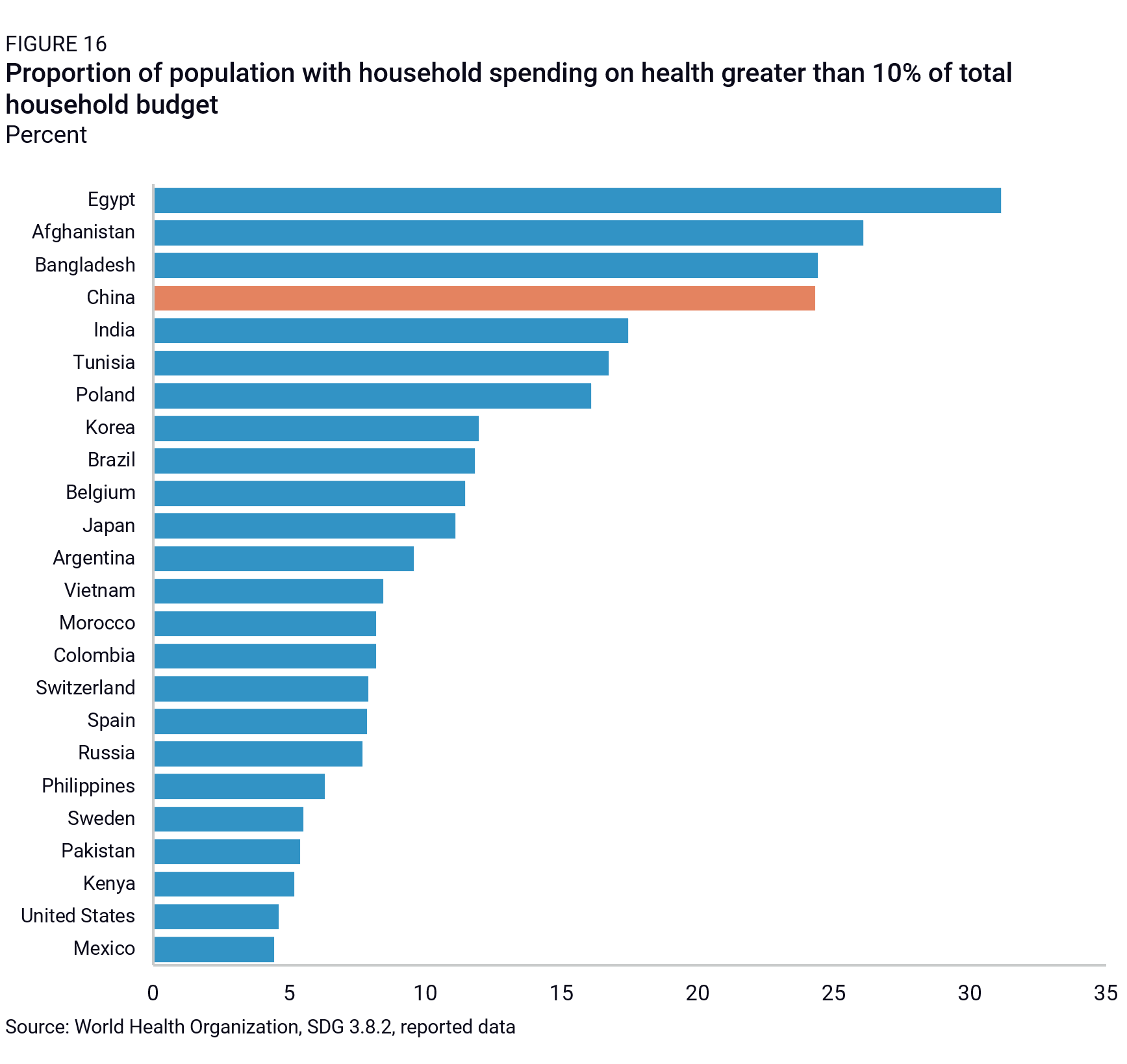

Heavy health expenditures are a particular risk for Chinese households, which face significantly higher levels of catastrophic health expenditure than other countries (Figure 16). Academic research found that wealthy households also faced high levels of catastrophic spending, which suggests that precautionary savings may not be limited to lower-income households.

The IMF has provided several studies of the empirical nature of China’s savings behavior, even at lower income levels. A review of the causes of China’s household savings from 2018 reveals that demographic changes explain much of the rise in savings, although precautionary savings also contributed. The one-child policy has almost certainly fueled higher retirement savings as well, with retirees needing to save given the assumed lack of support from their children. At the same time, the authors noted that there was still a considerable gap between Chinese savings rates at lower income levels and those in the rest of the world, contrary to Gan Li’s findings of low savings rates among lower-income households.

The view that precautionary savings are primarily responsible for weaker consumption clearly calls for more aggressive fiscal spending on China’s social safety net to change this behavior. The success of these measures, however, will depend upon how much in consumer spending these changes will release, and there is considerable evidence that savings are unequally distributed, and the low level of overall household income is a more pressing constraint.

Tax and fiscal policy and household consumption

If the low share of household income and the distribution of that income are the key constraints on household consumption, only fiscal transfers and government spending are likely to significantly impact future consumption growth. This section discusses the current state of tax and fiscal policy related to household consumption, and the need for significant changes in China’s fiscal system.

China currently has the scope to boost disposable incomes through fiscal policies, which are generally regressive. At the same time, China’s overall fiscal capacity is also declining over time because tax revenues are heavily dependent upon investment-led growth, and declining as a share of the economy. This increases the urgency of restructuring China’s fiscal system in the short term to kickstart rebalancing of the economy.

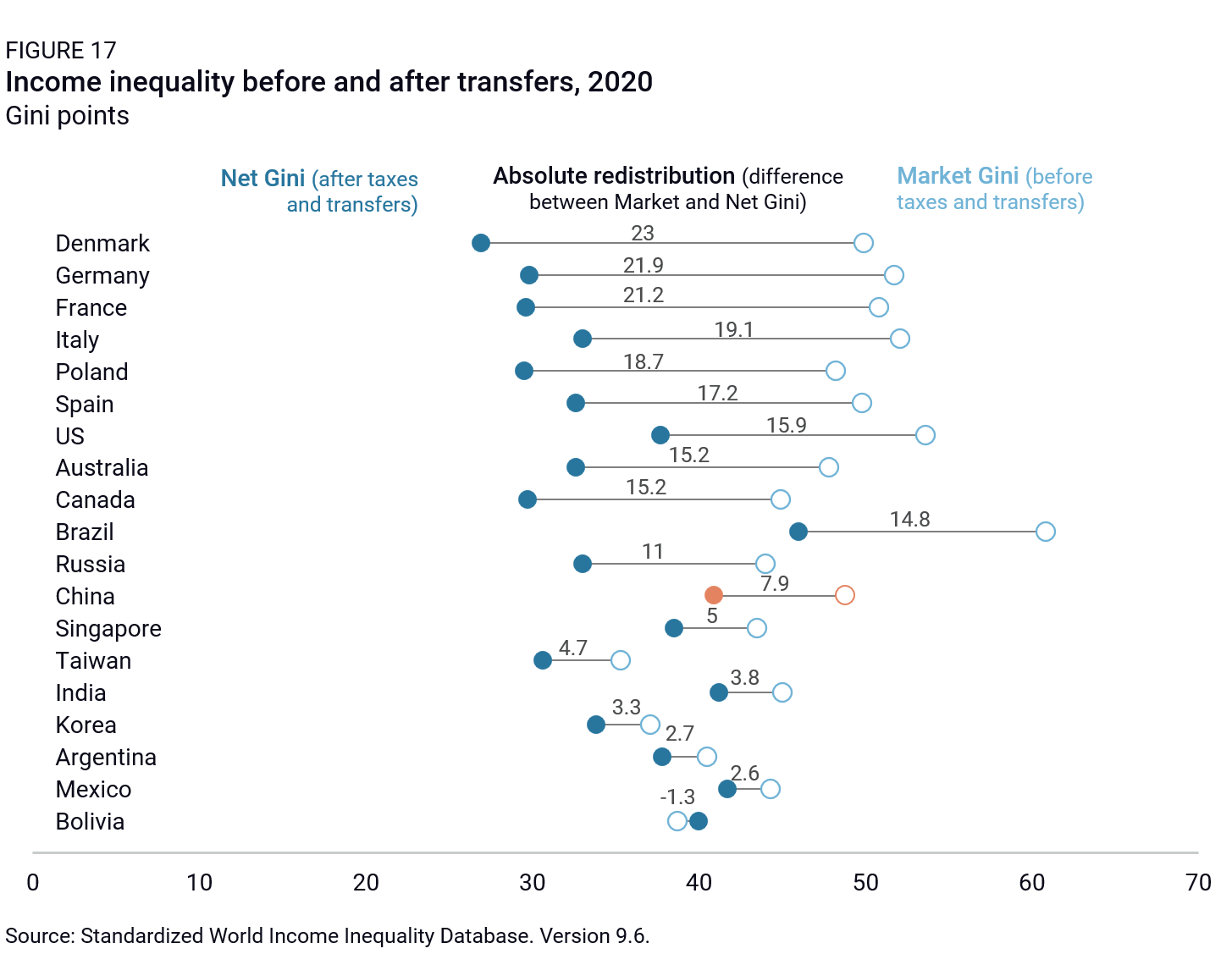

China’s fiscal expenditures for social transfers to households and basic services for citizens are low and less progressive than most other countries. China has a weak redistributive system, far behind the OECD average but also emerging countries like Brazil and Russia (Figure 17). Its social system is heavily skewed towards urban hukou holders, leaving behind about half its population. And its social transfers (both in cash and kind) and total fiscal expenditures as a share of GDP are well below the OECD average.

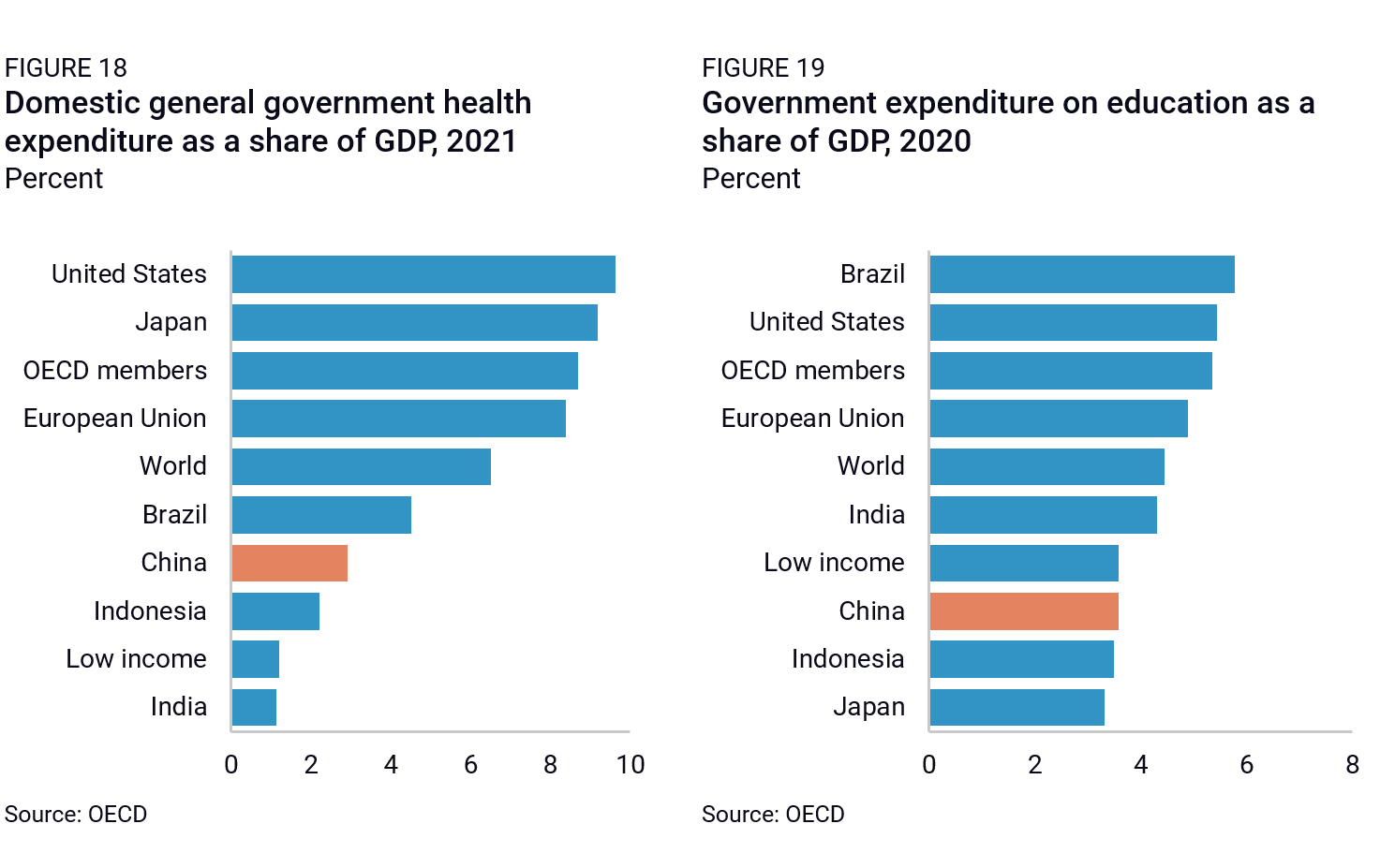

Increasing fiscal spending on basic services and social transfers

China’s low fiscal expenditures on basic services such as health and education place the country well behind OECD averages as a share of GDP (Figures 18 and 19). This means that households bear a larger part of the cost of education and health. Chinese households’ out-of-pocket expenditures accounted for 35% of total health spending in 2021, compared to only 13% in the OECD. China’s households spend an average of 17.1% of their annual income and 7.9% of their total annual expenditures on education, surpassing Japan, Mexico, and the US (1–2%) by significant margins. Poor households, in particular, allocate 56.8% of their income toward their children’s education, compared to only 10.6% among China’s higher-income households. Existing research indeed suggests a strong correlation between increases in health spending and savings rates in China.

Low tax revenues and a regressive taxation system

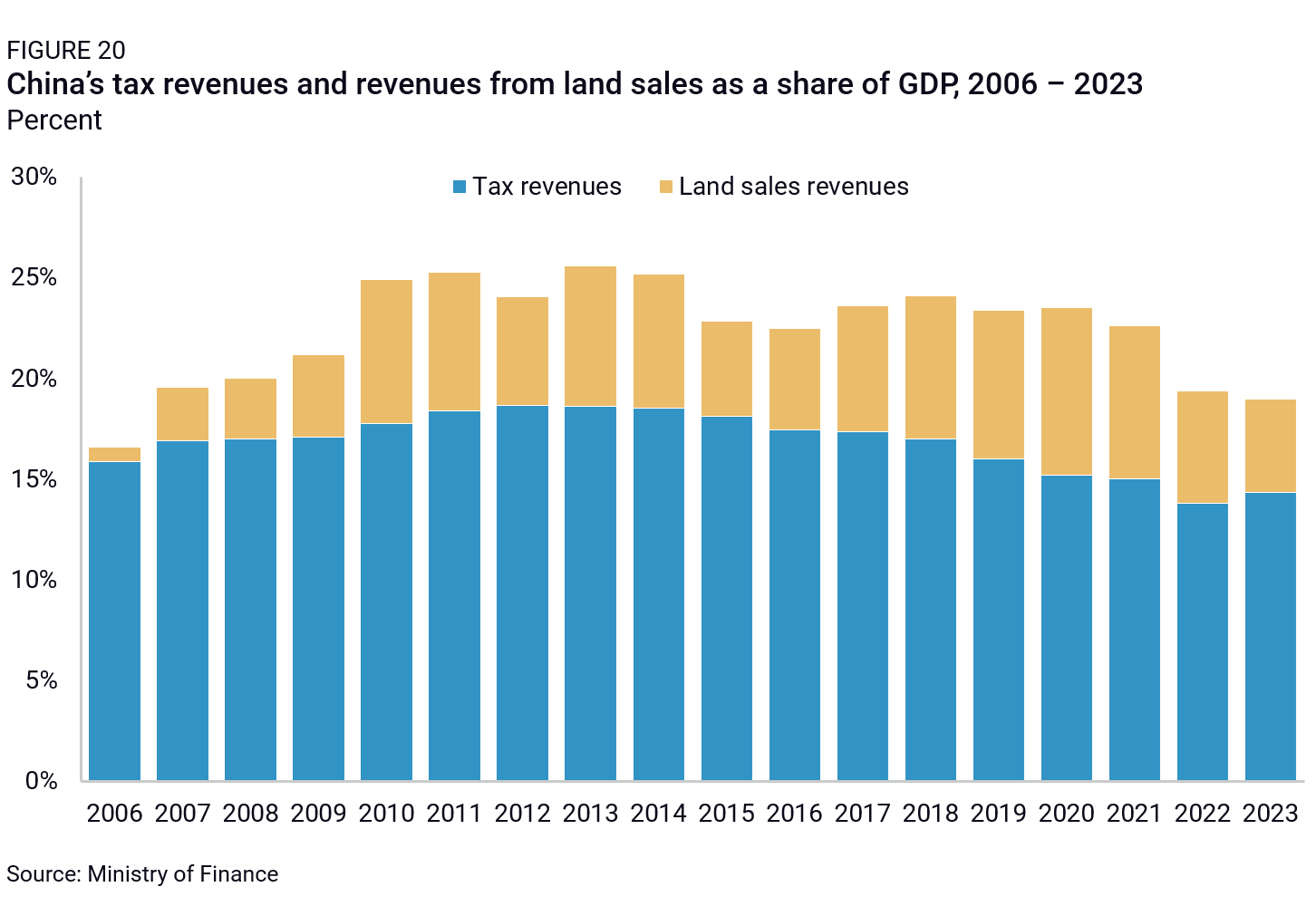

But the room to increase overall fiscal spending is becoming more limited because of China’s low (and declining) tax revenues. Over the past decade, China’s economic slowdown has strained public finances, resulting in reduced tax revenue growth. The central government has also provided major tax cuts every year since 2017, compounding the problem. While intended to stimulate the economy, these cuts further curtailed fiscal revenue growth. The tax revenue to GDP ratio fell from 18.5% in 2014 to 14.4% in 2023 (Figure 20). This fiscal crunch was compounded by the real estate slump and the fall in land sales in the past three years, since the sale of state-owned land use rights had become a key source of off-budget revenues for local governments.

China’s taxation system also disproportionately burdens poor households. According to IMF research, China’s combined effective tax burden on labor and capital is likely regressive across the income distribution. This is a strain on the disposable income of China’s poor households, which hampers consumption growth. Several types of reform could make China’s taxation regime more progressive while increasing the tax revenues available for fiscal transfers and social spending:

- Reforming the personal income tax regime: Tax bracket adjustments and an increase of the monthly basic deduction in 2018 made the personal income tax less progressive. A more progressive system could entail, for example, including non-wage income (such as business and capital income) in the tax base, capping special deductions, and adjusting the rates.

- Increasing capital income tax: Capital income tax is low in China, in contrast to international norms, and Beijing imposes high taxes on labor incomes. This creates wealth inequality, which constrains consumption among the poor.

- Implementing property and inheritance taxes: China has been piloting property taxes for many years, but there is no nationwide property tax regime yet. There is also no tax on inheritance and gifts. This allows wealthy Chinese households to maintain and pass on their wealth, entrenching inequality and constraining revenues available for fiscal transfers to the poor.

- A higher share of personal income taxes within tax revenues: The share of the personal income tax in total tax revenues is currently very small compared to OECD standards (8% in 2023 in China, compared with 24% in 2021 in OECD countries). Meanwhile, revenues from the value-added tax are much higher than the OECD average (38% in 2023, compared to 21% in 2021 in OECD countries). This makes China’s taxation system regressive as poorer households—who spend a larger proportion of their income on consumption—are disproportionately affected.

However, tax reform will face powerful vested interests and political resistance. The property tax, which has already been unveiled locally and mentioned repeatedly by the central government, has faced strong resistance that is likely to increase with the property market’s downturn. More broadly, raising taxes, no matter what kind, will remain unpopular among the newly taxed portion of the population or sector of the economy.

Changing central–local government fiscal relations

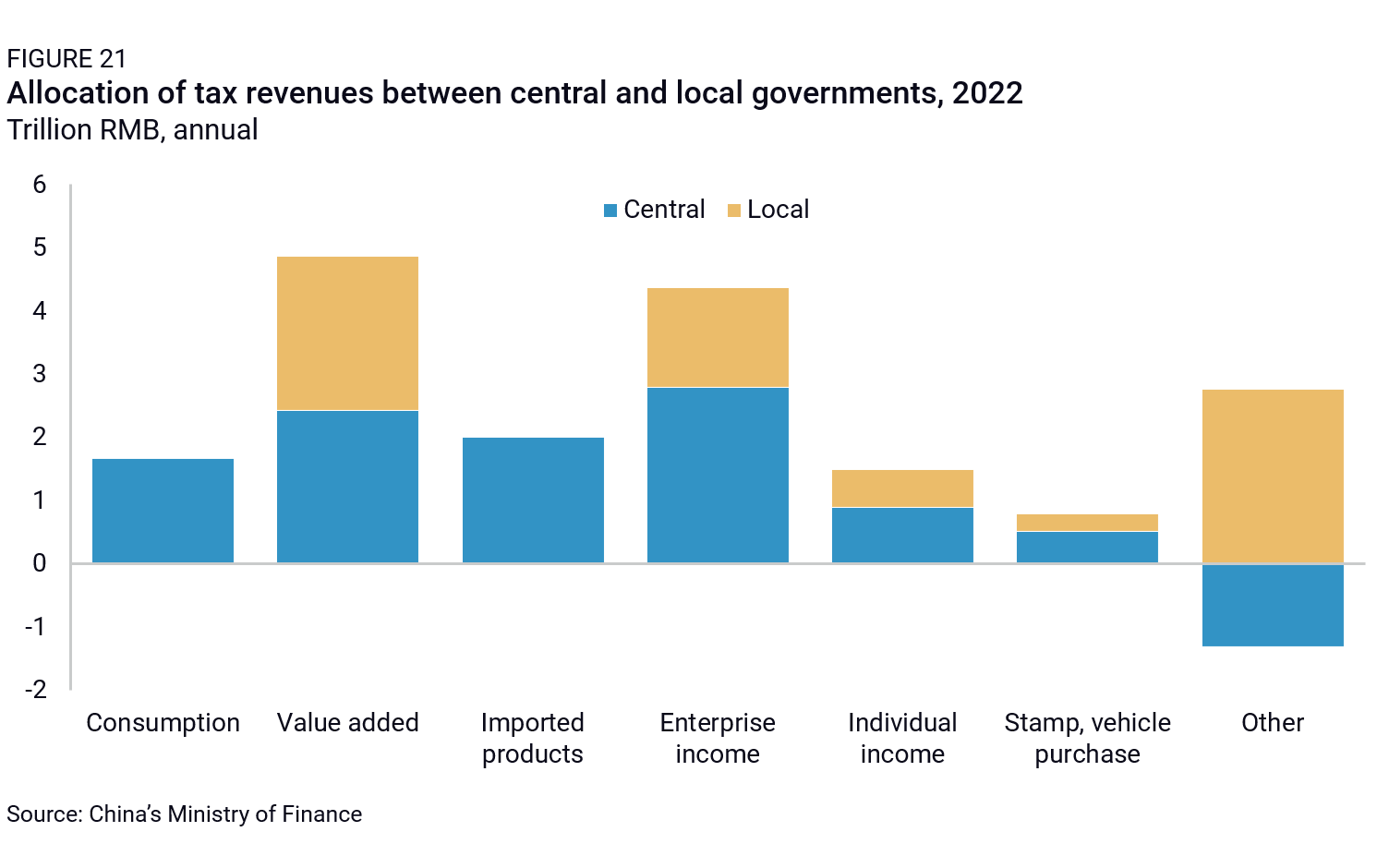

Increasing fiscal transfers and public expenditures is also challenging because it runs against the political and financial incentives of local government officials. Despite their central policy role, local governments have limited fiscal resources because of how funding is allocated between the central and local governments. After a major fiscal reform in 1994, local governments were left with less than half of China’s fiscal revenues (48.4% in 2020), with the other half going to the central government (Figure 21). Beijing then reallocates part of its revenues back to local governments, which makes them dependent on funding that they cannot control. In 2020, 27.8% of local fiscal expenditures came from centrally provided funds. But even after accounting for central transfers, local governments still face structural budget shortfalls.

This purposeful fiscal starvation pushes local governments to prioritize support for manufacturing and infrastructure. These sectors generate local revenues through land sales and create opportunities for graft and corruption, which maximizes cashflows to local coffers. In turn, local officials have fewer incentives to spend on basic services and social expenditures, which they mainly see as a drag on their finances.

The allocation of revenues between central and local governments also creates substantial differences in fiscal capacity across provinces. China’s persistent regional income gap is partly due to the growing fiscal pressure on China’s poorest provinces. Provinces with lower per capita GDP have less to tax, less money to work with, and have higher local government debt levels. As a result, there is little money to go around for fiscal expenditures to drive household consumption in these poorer provinces.

Changing the incentive structure would require a substantial overhaul of the central-local fiscal relationship. Beijing would need to take on more responsibility for basic services and social spending. But it has shown no sign, so far, that it is willing to significantly alter the system and increase central expenditures.

Longer-term impacts on household consumption

Beyond inequality, debt, and low incomes, other longer-term structural changes in China’s economy are likely to impact household consumption trends. The rising proportion of retirees would typically imply lower savings rates over time, but so far savings rates are still rising due to other factors in the equation. The gradual shift toward services and away from goods consumption may also slow the pace of aggregate consumption growth, as well as the impact of declining housing wealth on spending habits.

Changes in demographics and savings rates

China is on the cusp of a large transition toward a growing retired population that will rely on existing savings or pensions for spending in retirement. This was expected to reduce household savings, but this shift has not yet occurred. The retirement age in China remains extremely low by international standards, a legacy of historically lower life expectancies and state-owned enterprises as major employers. China’s average life expectancy reached 79 years in 2022, only slightly below 80.3 years in the OECD on average. With an effective average retirement age of around 54, United Nations population data imply that in 2013, around 297 million Chinese citizens were of average retirement age or older. By 2023, that number had ballooned to around 417 million, or around 30 percent of the population. By 2030, it is reasonable to assume that the population at 54 years of age or older will reach around 500 to 520 million.

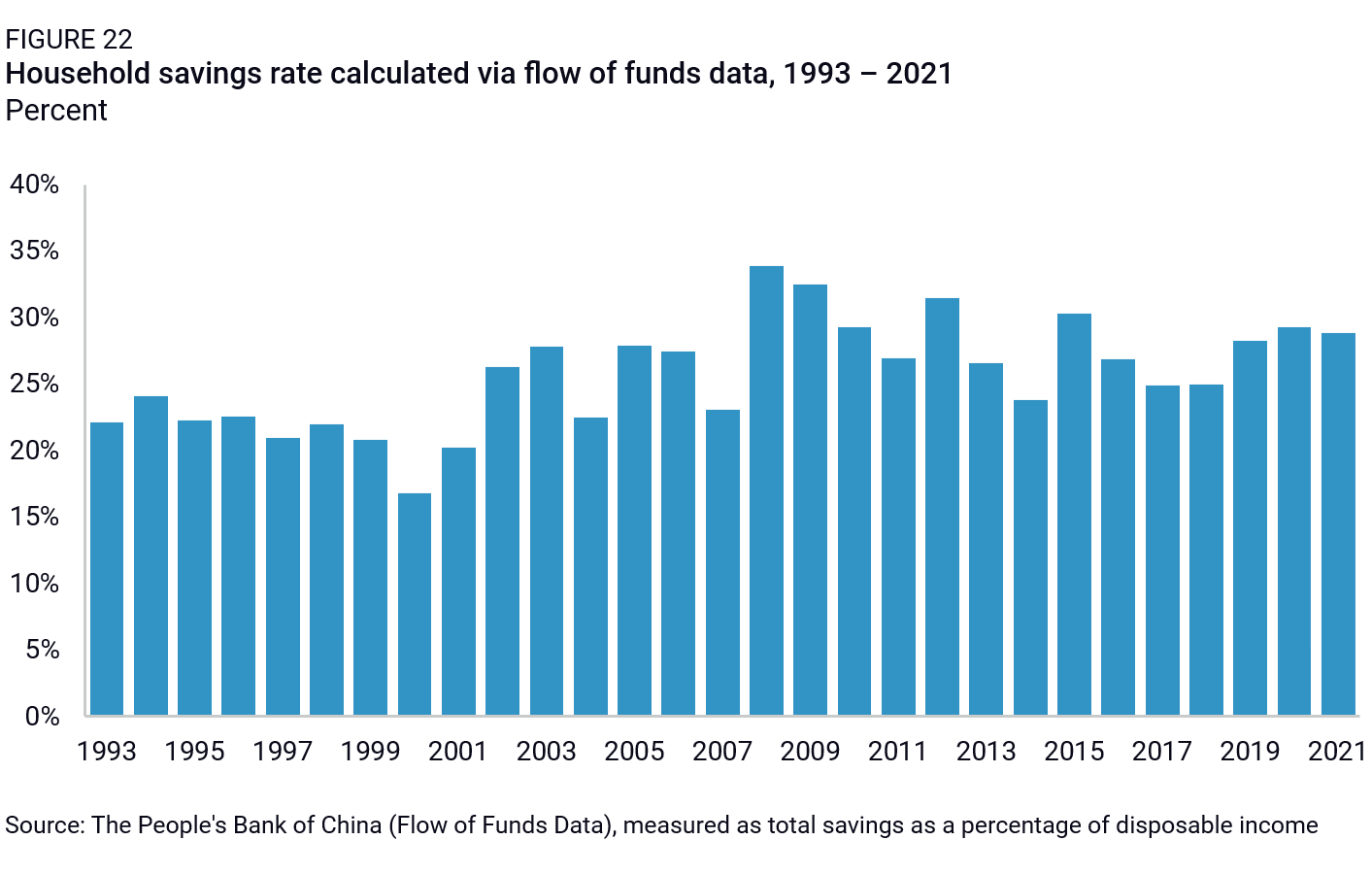

Most importantly, as the population approaching retirement age has already been rising, the aggregate savings rates in China have been stable or rising, rather than falling. Flow of funds data clearly indicate an increase in average household savings rates from 2013, when China’s working age population likely peaked, to 2021.

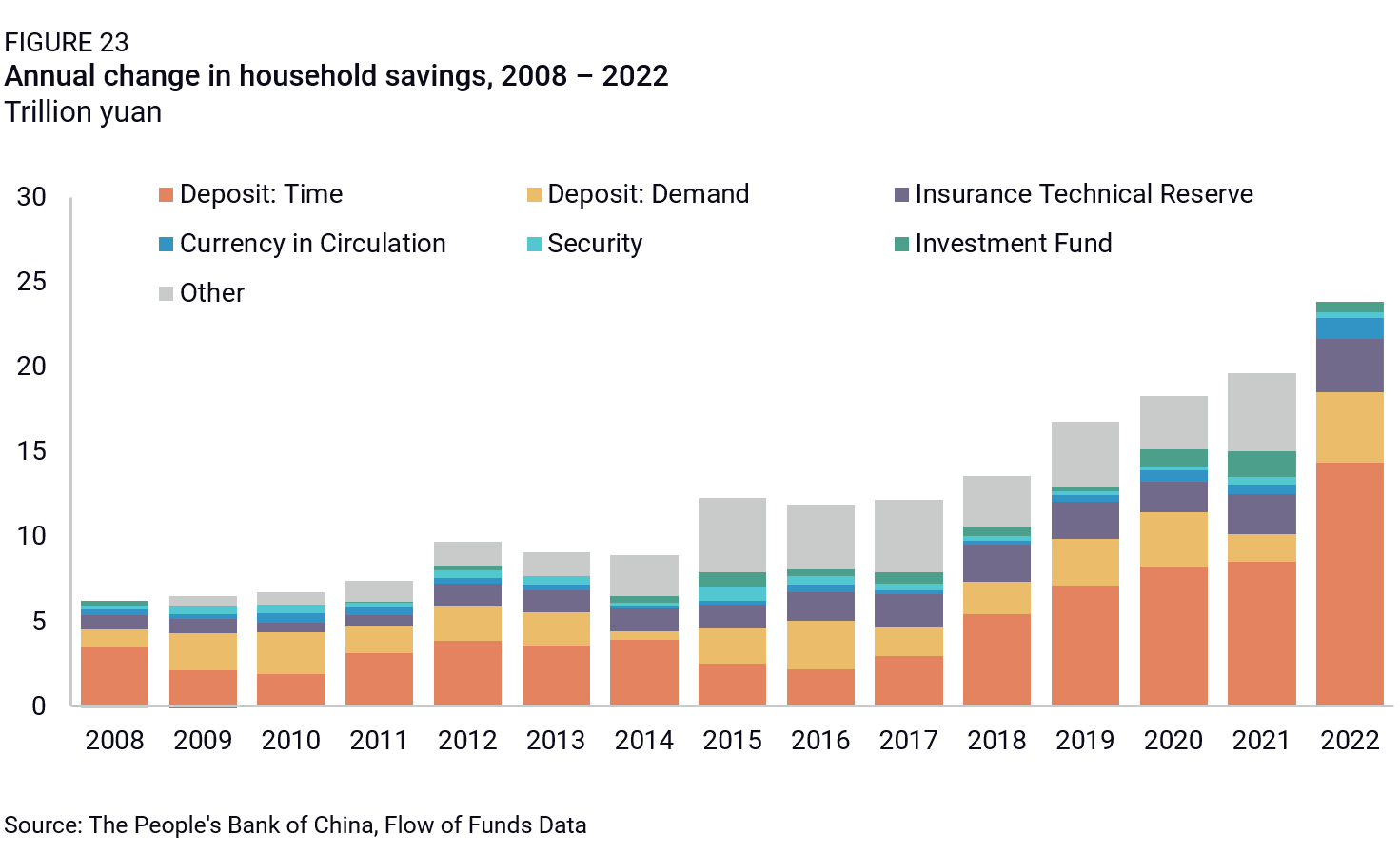

Since 2021, household savings have likely risen by larger proportions, given the weakness in consumer confidence, the slowdown in the economy, and the collapse in the property market. The growth in household savings has been strongest in time deposits, likely indicating the wealthy taking advantage of higher interest rates. Nonetheless, demographic factors do not yet appear to be actively reducing savings rates.

That can change, of course, and the growth of China’s household savings definitely benefited from planned savings for retirement, which would suggest lower savings and investment rates in the future, and additional consumption. But for the economy as a whole, there may be no clear trigger point at which these demographic effects become apparent relative to the other forces weakening consumption growth at present, given that the working age population has already been declining for over a decade, and the number of retirees has likely increased by around 40 percent since 2013.

Wealth effects from the property sector’s decline

Another key long-term uncertainty for household consumption stems from the decline in housing prices. Property was and likely remains the primary source of Chinese households’ net worth, with most estimates from household surveys placing housing around 60-80% of households’ assets. Property prices have been falling, likely since the start of the housing market’s adjustment in 2021. Consumer sentiment has remained extremely weak since 2022, reflecting the broader slowdown in the economy, but likely weaker property prices as well. Yet it will be difficult to determine any reasonable estimate for the negative wealth effect on consumption from falling property prices, in part because China had never seen a sustained downturn in the property market since its initial liberalization in the late 1990s.

One of the critical uncertainties in China’s housing market adjustment so far is how much housing prices have actually fallen. The data concerning housing prices is notoriously limited, as only certain cities publish housing transaction data, and nationwide price indices from the NBS usually reveal only very marginal changes in national housing prices (a decline of 13% from peak levels). Local governments not only attempted to administratively control housing prices by refusing to register transactions conducted outside certain price ranges when prices were falling, but when prices were rising as well. Secondary market housing prices can therefore serve as more reliable indicators, but only a small number of cities have liquid secondary markets that report housing sales prices as well.

Another unusual characteristic of China’s housing market adjustment has been the extent to which pre-construction sales drove both the surge in speculative activity and the decline. As the market became more dependent upon pre-construction sales, more investors and speculators were naturally involved in purchases—most owner-occupiers were unlikely to start paying a mortgage on a house that would only be delivered in two to three years, unless they believed strongly that prices would continue to rise. The result of that concentration of investors and speculators in the market likely weakens any negative wealth effect from the property sector’s decline, as those facing the largest losses were likely to be wealthier households who were less likely to consume a significant proportion of their incomes.

Overall, the importance of housing within China’s household asset distribution would suggest that a significant decline in housing prices will impact consumer confidence and overall spending levels. For new entrants to the housing market, lower prices may indicate less of a drag on disposable income in the future, but China’s homeownership rates remain above 80%, so most households will be impacted by falling prices. However, the magnitude of that negative wealth effect will be difficult to estimate, given that there is no history of housing price declines in China, and the fact that housing assets were distributed relatively unevenly in China, with the greatest losses likely accruing to the wealthiest households.

A gradual decline or a break from the trend?

The most probable outcome for long-term household consumption growth is a continued slowdown over time, below the current pace of urban per capita consumption growth of 6.0%, and consistent with the slowdown in China’s potential economic growth. But significant changes in policy or China’s economic trajectory could signal a change in that overall trend.

In addition to fiscal reforms, structural non-fiscal policies could also boost disposable income, lower inequalities, and significantly change the trends of household consumption in the years to come. The three main potential reforms involve hukou, social security, and land—three areas where China’s current system is discriminatory and unequal. However, reform within each of these areas faces significant constraints and there are distinct reasons reform has been slow so far.

Hukou reform

The hukou system, China’s household registration system, is likely the single biggest obstacle to consumption for a large part of the Chinese population. This system categorizes citizens as either rural or urban residents, determining their access to various social services and benefits. This system creates significant disparities between urban and rural populations, with migrants from rural areas often facing restrictions on accessing healthcare, education, and housing in cities. Removing hukou restrictions or relaxing the controls under the system would allow migrants to access services they had previously been denied, freeing up additional income for consumer spending.

The Chinese government is acutely aware of the issue and has gradually loosened the system over the past decade, particularly in small cities and for skilled workers. In 2022, the government issued a document proposing to eradicate hukou restrictions for all cities with a population under 3 million. But restrictions remain in China’s tier-one megacities, where a large proportion of migrant workers reside. More cities are now offering hukou status more liberally, often in exchange for new housing purchases. But these changes of hukou status to unlock additional consumption primarily work for recent migrants to those cities, rather than for households ready to purchase apartments.

Further hukou reform is likely to happen, but gradually. The rising public expenditures necessary to absorb China’s rural migrant population into urban basic services are daunting and will slow down any attempt at meaningful reform. Hukou reform that is meaningful enough to boost household consumption will likely require significant local fiscal reform as well.

Pension and health insurance

Another area where China could see gradual improvement is the pension and health insurance system. Both systems are currently divided into an employer-funded scheme for formally employed workers and a basic, state-funded “urban and rural residents” scheme for the others. In both systems, the basic scheme largely falls short in terms of funding and reimbursement, and companies frequently fail to comply with their compulsory participation. The urban employee pension plan, for example, paid around RMB 3,350 per month in 2020, against only RMB 174 for each person per month for the urban and rural residents scheme.

Enforcing companies’ compliance and allowing rural residents to claim their benefits, as well as significantly raising the benefits of the urban and rural residents’ schemes, would go a long way in boosting consumption. But we similarly expect gradual and slow improvements rather than major changes in the coming years. Local governments simply do not have the financial resources to substantially raise benefits, and they are also cautious about increasing the financial burden on companies that are already struggling under the pressures of the current economic slowdown.

Land reform

China’s current land ownership system is divided into urban land owned by the state and rural land collectively owned by villages. This restriction limits both the economic potential of land use and rural residents’ opportunities to benefit from urbanization and industrialization. Reforming land policies to allow more flexible land rights and easier transfer of land ownership could let rural residents unlock substantial wealth tied up in their land. This would enable farmers to lease or sell their land at market value, providing them with additional disposable income and reducing the urban-rural income gap.

But land reform also comes with challenges and risks. Historically, there has been strong resistance from localities at the village and township level to changing the rural ownership structure of land—localities would likely need some other source of revenue or some other asset as compensation. Furthermore, a land market that would unlock new sources of income for farmers would depend not only on a far more productive agricultural sector in China, but also a rising market for land prices in general, despite the recent downturn in the property sector. However, there is no other realistic option other than land reform outside of large-scale transfer payments to boost rural income and consumption levels.

Expectations of long-term consumption growth

International comparisons

China’s economy recently reached $12,000 in GDP per capita (sometime between 2021 and 2023, depending upon what year’s exchange rate is used), a level that is usually associated with the high end of “middle income” in a global context. Obviously, as economies become more developed, the period of “catch-up” growth has ended, and economic growth naturally slows, even if countries continue expanding and escape the well-publicized “middle income trap.” This slower pace of growth includes household consumption as well, as most major economies are consumption-led.

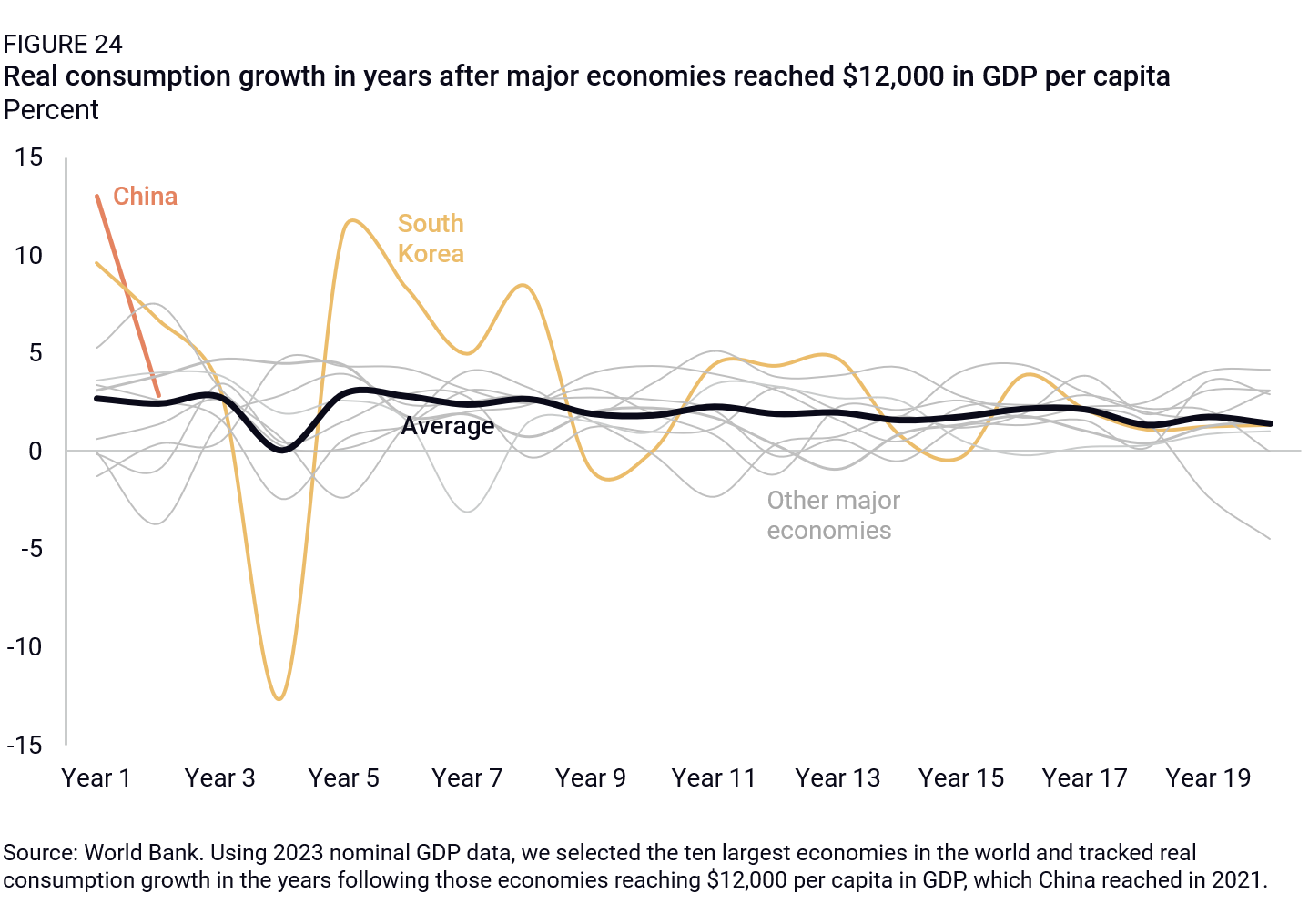

The chart below highlights the pace of real household consumption growth in the top ten economies in the world, during the twenty years after those economies reached the level of $12,000 in per capita GDP. The average pace of real household consumption growth in these economies was 2.3% in the first ten years after reaching this level, and 1.8% in the following ten years. The fastest pace of real household consumption growth in the first decade after reaching $12,000 in GDP per capita was in South Korea, at 3.9%. South Korea also passed that critical level of GDP per capita with a relatively low proportion of household consumption to GDP, which can partially explain the faster rate of growth relative to more developed economies.

The question these data raise is why China’s consumption growth would exceed the fastest rates of growth of any of these countries at similar stages of economic development, given China’s significant structural economic headwinds. These countries all still featured growing populations and labor forces, in contrast to China. South Korea’s experience after reaching $12,000 in GDP per capita was also rocked by the Asian financial crisis, contributing to more volatile growth. But on average, these countries saw real household consumption growth that was less than half of the pace China is currently reporting.

Outlook for long-term consumption growth and key uncertainties

Synthesizing all of this analysis into a forecast or range of expectations for household consumption growth in China over the next five to ten years is far from straightforward. The key considerations in compiling a long-term forecast in our view include:

- The most probable trajectory is that the ongoing and gradual slowdown in household consumption growth continues, rather than suddenly changing direction toward faster growth.

- As China continues to urbanize, rates of urban consumption growth are far more important for the outlook than rural consumption growth, with the important caveat that less than half of China’s population formally holds an urban registration.

- China’s declining population is likely to weaken overall consumption growth relative to the last decade, even if savings rates decline.

- China has already reached a reasonably high level of per capita GDP, which means that future rates of consumption growth are more likely to converge with global average rates rather than significantly exceed them. Still, given the current low level of consumption within China’s economy, it is reasonable to expect consumption growth will trend toward the higher end of the range among developed economies.

- The impact of the property sector’s price decline will have a small but meaningful negative impact on consumption growth over the next five years.

- Dramatic changes in policy to restructure China’s fiscal system and promote household consumption through transferring fiscal resources do not appear imminent, and cannot be assumed when forecasting consumption growth for the next decade.

- As the financial system continues its multi-year adjustment, credit-intensive investment will continue to decline. Household consumption is likely to outpace investment growth as credit expansion slows, but overall GDP growth will be below potential growth as capital formation falls below potential (A wide but reasonable range of estimates for long-term potential growth in China is 2.5-4.0%.) Household consumption will represent a larger share of GDP in the next 5 to 10 years, but overall GDP growth will slow.

Tying all of these strands together, the most probable range of China’s real household consumption growth over the next five to ten years is around 3 to 4%. This reflects the headwinds discussed above, along with the probability of a continued slowdown in urban per capita spending growth, from 6% in nominal terms over the past decade (and therefore around 5% in real terms). If the economy remains imbalanced and household consumption stays around 39% of China’s GDP, that means that consumption will contribute only around 1.2 to 1.6 percentage points of GDP growth per year for most of the next decade, a much lower contribution to growth than in the 2010s. Nothing in economic development is certain, but if the future looks roughly like the recent past, this is the most probable trajectory for household consumption growth.

Important uncertainties in our outlook include the prospect that household income is underreported within official data (particularly among lower-income households), the extent of the downturn in consumer confidence caused by the property market’s decline (or the potential improvement in confidence from a revival), and more abrupt policy changes to shift away from manufacturing and toward services-led growth.

However, by far the most significant uncertainty that might impact this outlook is the extent of reform to the fiscal system. China’s leadership has no magic bullets to rebalance the economy. Beijing must transfer resources away from the government and the wealthy and toward lower-income households. Consumption growth will remain tethered to household income growth and will remain constrained by income inequality. Altering the trajectory of household income growth and its distribution are therefore essential to change consumption patterns.

Beijing holds its economic fate in its own hands, but must relax its grip on politically motivated growth targets and the investment-led structures they have inspired. Regardless of how Beijing chooses to report the results of its efforts, we will be watching import levels, aggregate pricing trends, and nominal growth to reveal the progress and the tradeoffs in finally rebalancing China’s economy toward household consumption.

Footnotes

One of the primary proponents of this view is Michael Pettis, who has outlined the problems of rebalancing toward China’s consumption in The Great Rebalancing (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013) and Trade Wars are Class Wars (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), with Matthew Klein, among other publications.

Scott Rozelle et al, “Moving Beyond Lewis: Employment and Wage Trends in China’s High‑ and Low‑Skilled Industries and the Emergence of an Era of Polarization,” Comparative Economic Studies vol. 62 (2020), p. 555-589.